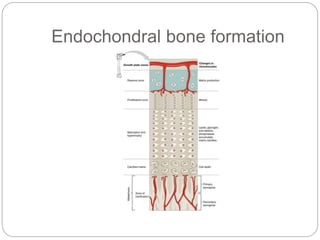

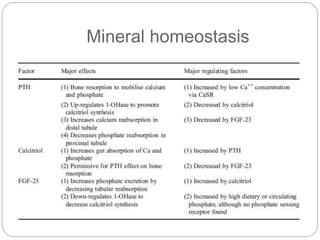

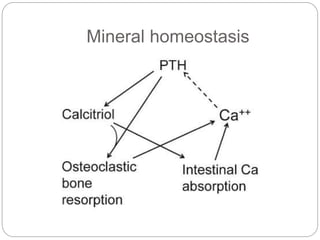

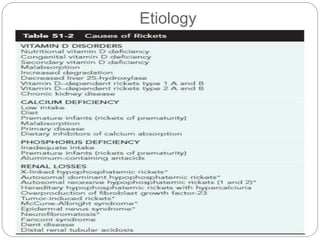

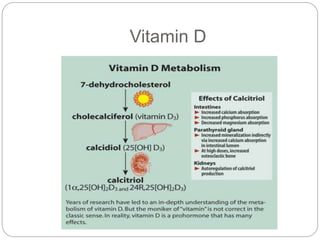

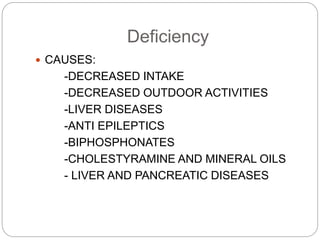

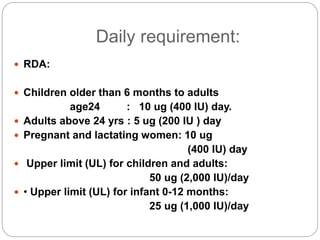

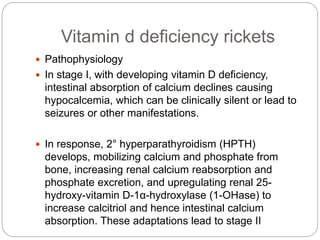

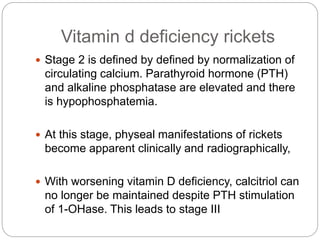

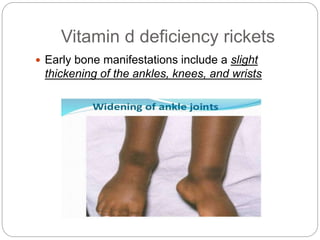

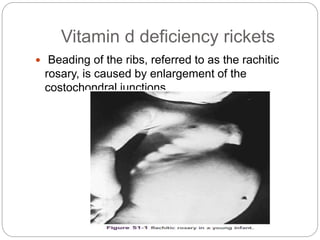

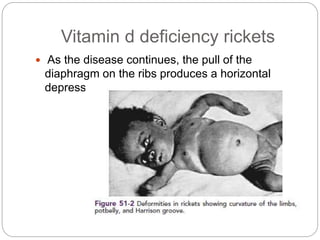

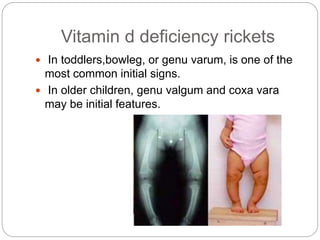

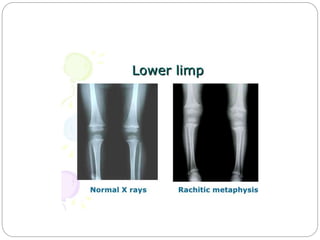

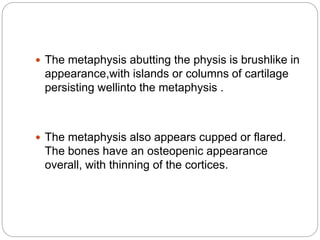

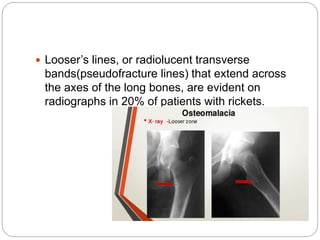

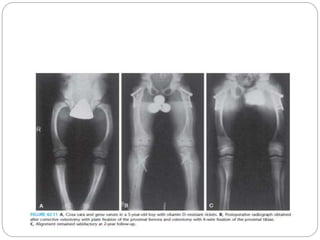

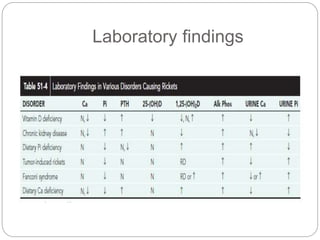

This document provides an overview of rickets and osteomalacia. It begins by defining rickets as a disease affecting the growth plates, causing deficient mineralization and impaired endochondral ossification due to failed apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Osteomalacia is a similar disorder affecting mineralization of osteoid. Both result from insufficient calcium and phosphate levels. Vitamin D deficiency is a common cause and treatment involves vitamin D supplementation. Other causes discussed include hereditary disorders, prematurity, drugs, tumors, and renal osteodystrophy. Clinical features, radiographic findings, and management approaches are described for each condition.