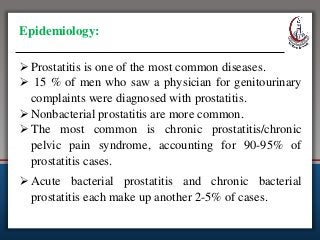

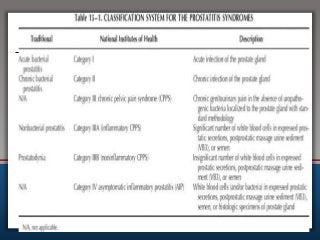

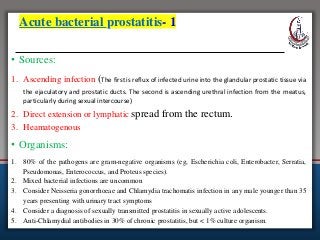

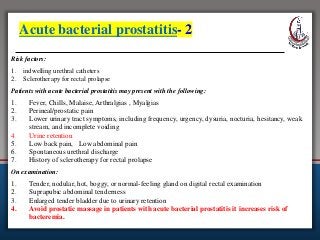

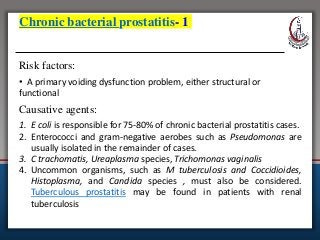

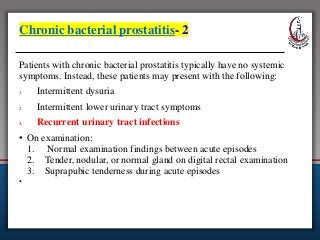

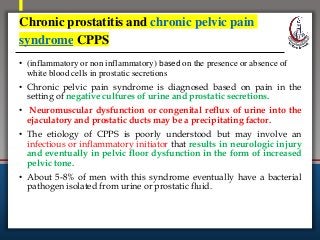

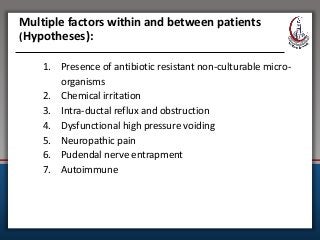

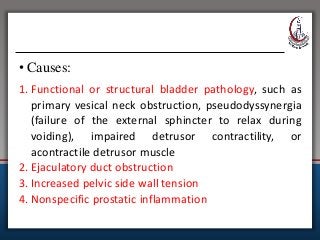

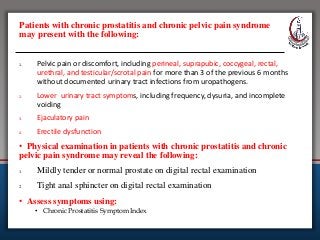

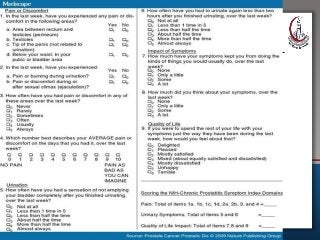

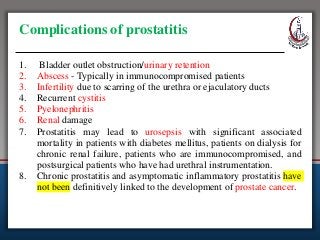

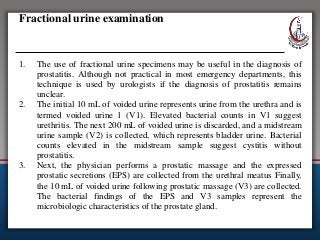

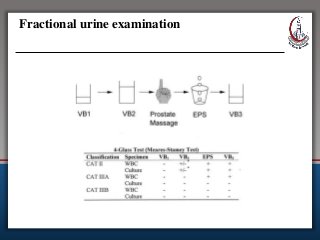

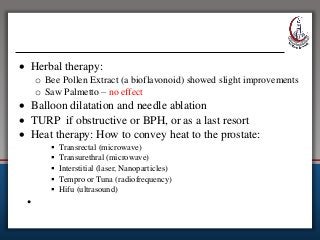

This document discusses prostatitis, an inflammation of the prostate gland. It describes the different classifications of prostatitis including acute bacterial, chronic bacterial, chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, and asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis. Treatment options are provided for different types, including antibiotics for acute bacterial prostatitis and supportive care. Diagnostic tests like urinalysis, EPS examination, and imaging are also outlined.