This document summarizes an experiment investigating high-temperature superconductivity in Yttrium Barium Copper Oxide samples. The experiment aimed to demonstrate the Meissner effect and zero resistance in the samples using liquid nitrogen. The document provides theoretical background on superconductivity, including the Meissner effect, Ginzburg-Landau theory, BCS theory, and the structure of Yttrium Barium Copper Oxide. It describes the experimental methods, results from Meissner effect tests, magnetic field experiments, X-ray diffraction analysis, and resistance measurements. The results are then discussed in relation to the theories of superconductivity.

![3

1. Introduction

While ‘low-temperature’ superconductors and their magnetic and electrical

properties have been studied since the 1910’s, high-temperature superconductivity is a

relatively new field of study. The first high-temperature ceramic superconductor, namely

a Lanthanum Barium Copper Oxide lattice (𝐿𝑎2−𝑥 𝐵𝑎 𝑥 𝐶𝑢𝑂4) with a critical temperature

of 30K [1], was discovered in 1986 by Georg Bednorz and K. Alex Müller, who subsequently

won the 1987 Nobel Prize in Physics. [2]

Superconductivity was first observed by Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes

in 1911 [3] while conducting super-cool experiments on samples of solid Mercury wire. He

observed that the electrical resistivity of the sample abruptly dropped to zero upon cooling

below the sample’s critical temperature, 4.2K (more precisely 4.15K using modern

thermodynamic scales) [4]. Onnes concluded that the sample had passed into a new

superconductive state, so named for its remarkable electrical properties. Onnes was also

unable to provide any form of residual resistance at the lowest temperatures, implying

that a superconductive material possesses zero D.C. electrical resistance. This

phenomenon has startling implications, one of which being the seemingly infinite

persistence of an electrical current within a looped superconducting wire, without

requiring an external power source [1].

This study specifically involves an analysis of only a few aspect of

superconductivity in a high-temperature, type II superconductor, namely an Yttrium

Barium Copper Oxide crystal lattice system (with the general formula 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂7−𝑥).

Details of the structure of Yttrium Barium Copper Oxide and the reason for our interest

in this structure will be discussed in chapter 2.6.

The outline of the report is as follows: in chapter 2 the theory concerning

superconductivity will be addressed, beginning with an overview of various concepts of

superconductivity that have been discovered within the last century. After this the

structure of Yttrium Barium Copper Oxide will be discussed, particularly its relationship

with the perovskite structure, and how the previously mentioned theoretical aspects of

superconductivity apply to the samples used in these experiments. Chapter 2 will also

include an analysis of the phenomenon known as the Quantization of Magnetic Flux.

Chapter 3 is concerned with the experimental aspects of this project; the apparatus used

will be included, as well as an explanation and an experimental realization of the sample.

Chapter 4 outlines the results of the experiment; measurement data from the Meissner

and magnetic field experiments will be provided in graphical form, along with graphs

demonstrating the relationship between lattice parameters and critical temperature with

Oxygen defects. X-Ray Diffraction patterns of each sample will also be provided, which

were required in order to determine a possible explanation for several of the disks (as well

as the powdered sample) failing to demonstrate superconductive properties. Chapter 5

will be used to discuss the results outlined in chapter 4, whereby the results of the

Meissner and magnetic field experiments will be analysed to determine if the Meissner

effect had been observed. The X-Ray diffraction patterns of the samples will also be

interpreted with an understanding of High-Tc superconductivity to provide an explanation

for the problem mentioned above. Aspects of the experiment that were not performed will

be discussed, as well as papers that have performed these investigations and how they

would have been implemented for this report. Chapter 6 will simply be used to conclude

the discussion of the results and to provide advice for possible future experiments in this](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-4-320.jpg)

![4

topic and for how to improve on this report’s investigations. Chapter 7 underlines the

acknowledgement of the author for the help received during research on the extremely

wide range of superconductivity background theory and while performing these

experiments.

2. Theoretical Aspects

2.1. Introduction to Superconductivity

Superconductors can be classified in two important ways. The most significant

classification for this report is the division of all superconducting materials by their

critical temperatures, Tc, the temperature at which the material enters the

superconductive state. Superconductors with a critical temperature below 30 Kelvin (K)

belong to the ‘low-temperature’ group, while those with a critical temperature above 30K

fall within the ‘high-temperature’ group.

Another criterion by which to classify superconductors is how the materials

respond to an external, applied magnetic field. If an applied magnetic field exceeds a

critical point (being a ‘critical’ magnetic field unique to every material) it will penetrate

the material, which induces a phase transition from the superconducting state to the

‘normal’ state. Type I superconductors are described by the Pippard theory rather than

the London theory, but the Pippard theory will not be discussed in this report as Yttrium

Barium Copper Oxide is a type II superconductor. Type I superconductors continue to

expel magnetic flux until the applied magnetic field exceeds the critical magnetic field, at

which point the material experiences a sudden phase transition. They usually consist of

pure metals and low concentration alloys. Type II superconductors possess two critical

magnetic fields; 𝐻𝑐1 and 𝐻𝑐2, which allows type II superconductors to occupy one of three

‘regimes’ [5].

If 𝐻 < 𝐻𝑐1 < 𝐻𝑐2 (where 𝐻 is the applied magnetic field) the superconductor is in

its superconducting state and occupies the same regime that a type I superconductor

would occupy when subject to an applied magnetic field below it’s critical value.

If 𝐻 > 𝐻𝑐2 > 𝐻𝑐1 the superconductor is in its normal state and occupies the same

regime that a type I superconductor would occupy when subject to an applied magnetic

field above its critical value.

If 𝐻𝑐2 > 𝐻 > 𝐻𝑐1 the superconductor is in what is commonly called the ‘mixed state’

or ‘vortex state’, in which the applied magnetic field partially penetrates the

superconductor. The parts of the superconductor which have been penetrated by the

magnetic field will be in their normal state with currents circulating around them. Type

I and II superconductors also have critical temperatures (which shall be discussed

shortly), which the critical fields of both type of superconductors are a function of.

Below, figure 2.1.1 shows a schematic variation of the magnetisation versus

critical magnetic field strength for type I and II superconductors, and in figure 2.1.2 shows

a characteristic phase diagram for type I and II superconductors.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-5-320.jpg)

![5

Figure 2.1.1 [6]: Schematic variation of induced magnetic field versus an applied

magnetic field. An induced magnetic field of zero implies that the material is no longer

superconducting.

The larger dotted triangle in figure 2.1.1 represents the abrupt switch of states

experienced by a type I superconductor as it transitions from the superconducting state

to the normal state (as its critical field is exceeded). The smaller triangle represents the

transition of a type II superconductor from the superconducting state to the mixed state

as 𝐻𝑐1 is exceeded, with a more gradual transition to the normal state as the applied

magnetic field penetrates more of the material.

Figure 2.1.2 [7]: Phase diagram for type I and type II superconductors. The phase

diagram for a type II superconductor is shown as a solid line.

In figure 2.1.2, while a type II superconductor lies below the 𝐻𝑐1 curve (curved due to the

critical magnetic field’s dependence on the temperature of the material), the

superconductor is in its superconducting state. However, if the superconductor lies above

the 𝐻𝑐2 curve (also curved due to the reason stated above) the superconductor is in its](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-6-320.jpg)

![6

normal state. Between 𝐻𝑐1 and 𝐻𝑐2 a type II superconducting material is said to be in its

mixed state. Above the dashed 𝐻𝑐 curve, a type I of superconductor is said to be in its

normal state. Alternatively if the material is below the 𝐻𝑐 curve it is said to be in its

superconducting state.

For the purpose of this report, a type II, high-temperature superconductor was

studied in our experiments. Although other variations of superconductors were not used,

it was still useful to research how to distinguish between them and their individual

properties.

2.2. Meissner effect

The Meissner effect (shortened from the Meissner-Ochsenfeld effect) was observed

by Walther Meissner and Robert Ochsenfeld in 1933 during an experiment intended to

demonstrate that superconductors were merely perfect conductors through the use of

classical electromagnetism [8]. In light of experiments performed by Onnes and Tuyn and

by applying Maxwell’s equations, Meissner and Ochsenfeld attempted to demonstrate

that the infinite conductivity of a material implies that bringing about any change of

magnetic field within the material is impossible, which also implies that flux within the

superconductor would become ‘frozen in’ at the instant of transition [9]. Contrary to their

predictions, superconductors behaved differently to a theoretically perfect conductor.

Their experiment involved subjecting a Lead sample to a weak magnetic field above its

critical temperature, and then reduced its temperature below 7.22 K [10], expecting

magnetic flux to have been trapped within the sample. This would have meant that a

subsequent removal of the applied magnetic field would have left the sample with internal

magnetic flux. However, it was observed that the internal magnetic flux was expelled,

giving an effective permeability of -1 (perfect diamagnetism) [11]. The magnetic field

strength immediately outside the lead sample increased, while the normal component of

the field appeared to be zero, indicating an expulsion of the internal magnetic field and a

perfect diamagnetic state. An interesting characteristic of the expulsion of flux is that the

phenomenon would occur whether a superconducting material was first placed in a

magnetic field and then cooled below the critical temperature or vice versa [8]; this was

particularly useful for our experiment, as it was difficult to place the rare-Earth magnet

above the sample before the sample was cooled.

If a superconductor in the normal state is subjected to an applied magnetic field

and then cooled below its critical temperature (or vice versa) an electric current rapidly

builds up on the superconductor’s surface, producing a magnetic field that suppresses the

magnetic flux within the interior, thus allowing the levitation of a magnet above the

superconductor [12]. Below is an illustration of the Meissner effect and how surface

currents are induced.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-7-320.jpg)

![7

Figure 2.2.1: [13] Image demonstrating the Meissner effect. (a) shows a

superconductor above its critical temperature (left), allowing magnetic flux to enter the

material, alongside an image of a superconductor below its critical temperature (right)

causing surface currents (represented by the red arrow) to circulate around the sample,

inducing a magnetic field which cancels the applied magnetic field. (b) demonstrates the

induced surface current loop levitating a magnet above a superconductor’s surface.

In fact, the applied magnetic field does penetrate the surface of the superconductor

to some extent within a thin layer, known as the penetration depth, which may be derived

from the London equations.

Developed by Fritz and Heinz London in 1935, the London equations explains the

Meissner effect. The equations describe the exponential expulsion of all internal magnetic

fields from a superconducting material as it transitions to the Meissner state (for clarity

the ‘Meissner state’ and the ‘Superconducting state’ are synonymous). There are several

ways to justify the London equations, but perhaps the most acute is the quantum method

involving the vector potential A, given by Fritz London [14]. Noting that the

superconducting current density is defined as

𝒋 𝒔 = 𝑛 𝑠 𝑒𝒗 (2.2.1)

where 𝑛 𝑠 is loosely associated with the number density of superconducting carriers, e is

the electronic charge and 𝒗 is the velocity of the charge carriers. The canonical

momentum is defined as

𝒑 = 𝑚𝒗 + 𝑒𝑨/𝑐 (2.2.2)

where m is the electron mass and c is the speed of light. The ‘single’ London equation can

be described by using Bloch’s theorem to argue that the canonical momentum in a

system’s ground state is zero, and by combining equations 2.2.1 and 2.2.2 it can be shown

that

𝒋 𝒔 = −

𝑛 𝑠 𝑒2

𝑨

𝑚𝑐

(2.2.3)

Taking the time derivative of both sides of equation 2.2.3 yields the first of the London

equations;

𝜕𝒋 𝒔

𝜕𝑡

=

𝑛 𝑠 𝑒2

𝑚

𝑬

(2.2.4)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-8-320.jpg)

![8

where E is the electric field. Taking the curl of both sides of 2.2.3 leads to the second

London equation;

∇ × 𝒋 𝒔 = −

𝑛 𝑠 𝑒2

𝑚

𝑩

(2.2.5)

where B is the magnetic field. By applying Ampere’s Law to 2.2.5 it can be manipulated

[14] to produce the following equation;

∇2

𝑩 =

1

𝜆2

𝑩

(2.2.6)

where

𝜆 ≡ √

𝑚𝑐2

4𝜋𝑛 𝑠 𝑒2

whereby 𝜆 is the London penetration depth, implying a characteristic length scale at

which an applied magnetic field becomes exponentially weaker than the magnetic field at

the surface of the superconductor [15].

2.3. Ginzburg-Landau Theory

The Ginzburg-Landau (GL) Theory was initially postulated as a macroscopic model

to describe type I superconductors without examining their microscopic properties in

great detail. However, a version of the GL theory was later derived from the Bardeen-

Cooper-Schrieffer theory by L. P. Gor’kov, demonstrating that it can be interpreted

microscopically, e.g. the order parameter of the GL theory is related to the wave function

of Cooper pairs [16].

Developed by V. L. Ginzburg and L. Landau in the 1950’s, they proposed the

introduction of a quantity, Ψ, known as the order parameter, which is defined as equal to

zero for a normal region and unity for a fully superconducting region at T = 0 [17]. Ψ was

taken to be a complex quantity, the modulus squared of which was equal to the number

density of superconducting charge carriers, such that

|Ψ(𝑟)|2

= 𝑛 𝑠(𝑟)

Based on a theory established by Landau on second-order phase transitions, the

free energy of a superconducting system near transition can be expressed as a power

series in |Ψ|2

, the coefficients of which are functions of temperature [18], such that

𝐹 = 𝐹𝑛 + 𝛼|Ψ|2

+

𝛽

2

|Ψ|4

+

1

2𝑚

|(−𝑖ℏ∇ − 2𝑒𝑨)Ψ|2

+

|𝑩|2

2𝜇0

(2.3.1)

where 𝐹𝑛, e and m are the free energy of the normal state in which Ψ = 0, the effective

mass and the electron charge, respectively, A is the magnetic vector potential, B is the

magnetic field such that 𝑩 = ∇ × 𝑨, and 𝛼 and 𝛽 are phenomenological parameters. By

minimizing the free energy with respect to Ψ and A, one arrives at the two GL equations;

𝛼Ψ + 𝛽|Ψ|2

Ψ +

1

2𝑚

|(−𝑖ℏ∇ − 2𝑒𝑨)|2

Ψ = 0

(2.3.2)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-9-320.jpg)

![9

𝒋 =

2𝑒

𝑚

(Ψ∗(−𝑖ℏ∇ − 2𝑒𝑨)Ψ)

(2.3.3)

where j is the current density which is equal to the superconducting current density while

the material is in the superconducting state [19]. It is worth mentioning that the 2𝑒 within

the modulus of equation 2.3.2, the first GL equation, was previously denoted 𝑒∗

, being the

effective charge of the superelectron wavefunction. The denotation was later changed to

account for Cooper Pairs [20] (which will be discussed in section 2.4). The physics behind

the derivation of the two GL equations is rather complicated and therefore will not be

discussed in full in this report.

The second GL equation may be re-written as

𝒋 𝒔 = −

2𝑒ℏ𝑛 𝑠

𝑚

(∇𝜃 +

2𝑒𝑨

ℏ

)

(2.3.4)

by setting

Ψ = 𝑛 𝑠

1

2

𝑒 𝑖𝜃

|Ψ|2

= 𝑛 𝑠 = −

𝛼

𝛽

which follows from the London approximations of a homogeneous superconductor below

𝑇𝑐

[19] [21] [24], whereby

𝛼(𝑇) = (

𝑑𝛼

𝑑𝑇

)

𝑇𝑐

(𝑇 − 𝑇𝑐) for 𝑇 ≤ 𝑇𝑐

𝑑𝛼

𝑑𝑇

> 0 for 𝑇 = 𝑇𝑐

𝛽 = 𝛽(𝑇𝑐) ≡ 𝛽𝑐 > 0

By then taking the curl of equation 2.3.4 (the second GL equation), while considering that

∇ × ∇𝜃 = 0 and ∇ × 𝑨 = 𝑩, one arrives at

∇ × 𝒋 𝒔 = −

4𝑒2

𝑛 𝑠

𝑚

𝑩 (2.3.5)

Also worth considering is

𝜇0∇ × 𝒋 𝒔 = ∇ × (∇ × 𝑩) = −∇2

𝑩

Thus equation 2.3.5 can we rewritten as](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-10-320.jpg)

![10

∇2

𝑩 =

𝑩

𝜆2

where

𝜆 = √

𝑚

4𝜇0 𝑒2 𝑛 𝑠

= √

𝑚

4𝜇0 𝑒2|Ψ|2

which demonstrates that the second GL equation is in accordance with the second London

equation under certain conditions, meaning that the GL theory can predict the Meissner

effect and that the London equations are consequences of the coherence of a quantum

state [23].

Equation 2.3.2 is a non-linear form of the free-particle Schrödinger equation and

can be rearranged to

𝜉2

∇2

Ψ + Ψ −

𝛽

|𝛼|

|Ψ|2

Ψ = 0

Where

𝜉 = √

ℏ2

2𝑚|𝛼|

(2.3.6)

whereby 𝜉 is the coherence length and is defined as the parameter by which |Ψ| varies

due to small perturbations in superconducting electron density. Equation 2.3.6 is valid

only for superconductors in the normal state. The coherence length of superconductors in

the Meissner state can be defined as

𝜉 = √

ℏ2

4𝑚|𝛼|

Whereby 𝑚 in equation 2.3.6 is replaced by 2𝑚 due to the formation of Cooper pairs in the

Meissner state. A new parameter can be defined from the coherence length and

penetration depth of the material known as the Ginzburg-Landau parameter;

𝜅(𝑇) =

𝜆(𝑇)

𝜉(𝑇)

and remains finite as 𝑇 → 𝑇𝑐. Type I superconductors are defined by 𝜅 < 1/√2 and type II

superconductors are defined by 𝜅 > 1/√2 [24].

2.4. BCS Theory

To begin, it is worth mentioning the importance of H. Fröhlich’s model of electron-

phonon interactions. While the model was specified for metals, it is applicable to other

materials. The model describes continuous phononic interactions of an electron with its

surrounding lattice, causing perturbations in its neighbouring atoms, to which the

electron reacts [25]. Fröhlich argued that this interaction could produce a ground state of

lower energy electrons relative to the Fermi level of non-interacting electrons, and that

this Superconducting ground state would be separated from normal conducting states by

an energy gap (the Fermi level) [26]. Although ‘gapless’ superconductors exist, they will not](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-11-320.jpg)

![11

be discussed in this report. The phonon-electron interaction model was supported by two

experimental investigations in the 1950’s on the variation of 𝑇𝑐 as 𝑀−1/2

, where M is the

isotopic mass [27] [28], which is a result of the model if phonon-electron interactions are

important.

L. N. Cooper was the first to propose an electron-phonon-electron interaction which

could result in a reduction of the Coulomb repulsion between two electrons in the

superconducting state, relative to the normal state [29]. Cooper suggested the following

sequence of events: an electron induces the creation of a phonon as it deforms the

surrounding lattice by attracting positive charges; the phonon then propagates through

the lattice and is subsequently absorbed by another electron with opposite spin; the

second electron then moves into a region of higher positive charge density. Since the

phonon exchange is virtual, energy is conserved in the lattice, but not between the two

electrons. With this suggestion, Cooper showed that if the phonon exchange resulted from

an attractive interaction (regardless of origin), a bound state of an electron pair could

result [30].

Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer then followed this suggestion by showing that

bound pairs of electrons of opposing spin and exactly opposite values of wave vector, could

form under favourable conditions [31] [32]. The existence of these ‘Cooper pairs’ is strongly

implied by evidence from flux quantisation experiments, which will be discussed in section

2.5.

While Cooper pairs are symmetric about 𝒌 = 0 for a superconductor with zero

current density, where k is the wave-vector in a non-vanishing persistent current

situation, the Fermi sphere is shifted bodily. This results in all Cooper pairs gaining a

non-zero momentum. The current carried by these Cooper pairs cannot be relaxed by

phonon activity or local defects due to the energy gap stabilising them from small net

changes of momentum; the breaking of a single pair would change the energy of the entire

‘condensed’ state of pairs, thus the energy required to break a single Cooper pair is related

to the energy required to break all Cooper pairs. This gives rise to the infinite (D.C.)

conductivity of superconductors as an essential consequence of BCS theory [25]. The BCS

theory also implies the Meissner effect, but to demonstrate this is beyond the level of this

report.

2.5. Quantisation of Magnetic Flux

F. London predicted the quantisation of magnetic flux trapped within a

superconducting ring in the 1950’s, implying that a quantum mechanical effect is

observable on the macroscopic scale [33] [34]. Flux quantization has been observed in type I

and type II superconductors, primarily in situations involving a superconducting material

surrounding a non-superconducting hole (e.g. a hollow superconducting cylinder,

superconducting ring or a superconducting toroid. A superconducting material subjected

to an applied magnetic field is cooled below its critical temperature, causing magnetic flux

to be ejected from the material. However, the magnetic flux will not be ejected from the

inner non-superconducting region. A subsequent removal of the applied magnetic field

would result in the trapping of the flux lines within this region and are maintained by

persistent currents in the surrounding superconducting material [15].

London also predicted the quantized units of the trapped magnetic flux as](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-12-320.jpg)

![12

Φ 𝑜 =

2𝜋ℏ

𝑒

= 4.14 × 10−15

𝑊𝑏

based on the suggestion that the trapped magnetic flux should be quantized since

superconductivity is overtly a quantum phenomenon [35].

The method of deriving the flux quantum value discussed in this report involves

employing the time-dependent Schrödinger equation to derive the second GL equation

and integrating around a closed loop. The Cooper pair condensate can be described as a

single macroscopic wave function

Ψ(𝒓, 𝑡) = |Ψ(𝒓, 𝑡)|𝑒 𝑖𝜃(𝒓,𝑡) (2.5.1)

where Ψ(𝒓, 𝑡) is the quantum mechanical wave function, |Ψ(𝒓, 𝑡)| is the amplitude of the

wave function and 𝜃(𝒓, 𝑡) is the phase at position r and time t [36]. Equation 2.5.1 must

obey the time-dependent Schrödinger equation [37]

[

1

2𝑚

(

ℎ

𝑖

∇ − 𝑞𝑨)

2

+ 𝑞Φ] Ψ = 𝑖ℏ

𝜕Ψ

𝜕𝑡 (2.5.2)

Where m and q are the mass and charge of the Cooper pairs, respectively and Φ(𝒓, 𝑡) is

the scalar potential. By multiplying equation 2.5.2 by Ψ∗

and by subtracting its complex

conjugate, one finds

−∇ ∙ [

ℏ

2𝑚𝑖

(Ψ∗

∇Ψ − Ψ∇Ψ∗) −

𝑞

𝑚

|Ψ|2

𝑨] =

𝜕

𝜕𝑡

(Ψ∗

Ψ)

(2.5.3)

and by multiplying equation 2.5.3 by q one obtains the equation of electromagnetic

continuity

−∇ ∙ 𝒋 𝒔 =

𝜕𝜌𝑠

𝜕𝑡

where 𝜌𝑠 is the charge density and

𝒋 𝒔 =

ℏ𝑞

2𝑚𝑖

(Ψ∗

∇Ψ − Ψ∇Ψ∗) −

𝑞2

𝑚

|Ψ|2

𝑨

(2.5.4)

Which may be rearranged to produce equation 2.3.3. By substituting equation 2.5.1 into

2.5.4 and by assuming that Ψ∗

Ψ can be interpreted as the local charge carrier density, 𝑛 𝑠,

one arrives at

𝒋 𝒔 =

ℏ𝑞𝑛 𝑠

𝑚

(∇𝜃) −

𝑞2

𝑛 𝑠

𝑚

𝑨 (2.5.5)

By integrating equation 2.5.5 around a closed loop Γ [33] [38] [39], one obtains

∮ 𝒋 𝒔

Γ

. 𝑑𝒍 = ∮

ℏ𝑞𝑛 𝑠

𝑚Γ

(∇𝜃). 𝑑𝒍 − ∮

𝑞2

𝑛 𝑠

𝑚Γ

𝑨. 𝑑𝒍 (2.5.6)

By invoking Stokes’ Theorem](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-13-320.jpg)

![13

∮ 𝑨

Γ

. 𝑑𝒍 = ∮(∇ × 𝑨)

s

. 𝑑𝑺 = ∮ 𝑩

s

. 𝑑𝑺 = Φ

by recognising that equation 2.5.1 must be single valued and that integrating ∇𝜃 around

a closed loop yields 2𝜋𝑥 (𝑥 ∈ ℝ), and by also assuming that the path of integration is a line

where 𝒋 𝒔 = 0 [39], equation 2.5.6 may be rearranged to predict flux quantization [40];

ℏ𝑞𝑛 𝑠

𝑚

(2𝜋𝑥) =

𝑞2

𝑛 𝑠

𝑚

Φ

⇒ ℏ(2𝜋𝑥) = 𝑞Φ

⇒ Φ =

ℎ

𝑞

𝑥 = 𝑥Φ0

in which

Φ0 ≡

ℎ

|𝑞|

=

ℎ

2𝑒

= 2.07 × 10−15

𝑊𝑏

(2.5.7)

Which is half the value predicted by London.

Equation 2.5.7 (with the implication of −2𝑒 as the fundamental superconducting charge)

agrees with the Cooper pair concept of BCS theory and the suggestion that charge carriers

in a superconductor in the Meissner state are pairs of electrons of opposite spin and wave

vector. This has been verified in various experiments whereby magnetic flux has been

isolated [41] [42].

2.6. Yttrium Barium Copper Oxide

It would be useful to begin this section by discussing the perovskite structure. A

compound with a crystalline structure similar to that of Calcium Titanium Oxide is said

to possess a perovskite structure. Perovskite compounds typically have the chemical

formula of 𝐴𝐵𝑋3 where A and B are different species of cation (whereby A is drastically

larger than B) and X is an anion (typically a species of Halogen) that bonds with both

cation species [43]. The ideal perovskite structure is a cubic unit cell consisting of a primary

cation (A) at the centre of the unit cell, another cation (B) at each corner of the unit cell,

and an octahedron of anions at the face-centred positions [44]. The relative ion sizes

required for the stability of the cubic lattice are precise, therefore deviation (e.g. anion

octahedral tilt or distortion, cation displacement etc.) [45] from these requirements may

result in lower-symmetry distortions of the perovskite structure. The most common

perovskite distortions are the orthorhombic and tetragonal non-cubic variants. The

orthorhombic variant results from the cubic lattice stretching along two of its orthogonal

pairs by different factors, resulting in a rectangular prism with a rectangular base (such

that 𝑎 ≠ 𝑏 ≠ 𝑐). The tetragonal lattice results from the cubic lattice stretching along one

of the lattice vectors, resulting in a rectangular prism with a square base (such that 𝑎 =

𝑏 ≠ 𝑐 where c is the height of the lattice). Certain complex perovskite structures contain

two different B-site cations, one of which is Yttrium Barium Copper Oxide. This property

can result in ordered and disordered variants, which can result in dramatically different

electrical properties, which will be discussed shortly.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-14-320.jpg)

![14

Figure 2.6.1: Image of the ideal perovskite structure, shown as bonded atoms (left)

and as conrner-linked octahedra (right) [44] The primary cation, secondary cations and

anions are denoted by the red, blue and green circles, respectively.

Yttrium Barium Copper Oxide (YBCO) is a crystalline compound consisting of an

orthorhombic lattice structure (with the following ideal orthogonal parameters; 𝑎 =

3.823 Å, 𝑏 = 3.885 Å, 𝑐 = 11.7 Å) [50], resulting from a defective perovskite structure [46].

The YBCO unit cell consists of a layer of CuO, a layer of BaO surrounded by four Oxygen

ions, a layer of 𝐶𝑢𝑂2 surrounded by 5 Oxygen ions in a polyhedral shape, and a layer of

Oxygen-deficient Yttrium. Below is an illustration of the structure of YBCO.

Figure 2.6.2: Image of the YBCO structure, consisting of a perovskite-like

structure with an orthorhombic lattice system whereby 𝑎 ≠ 𝑏 ≠ 𝑐 with all three

orthogonal bases intersecting at 900 [47].

The 𝐶𝑢𝑂2 planes along the b-axis directly above and below the Yttrium atom have

two Oxygen atoms per Copper atom, which compared to the ideal perovskite structure

(where four Oxygen atoms would be present) are said to be Oxygen deficient; these Copper

Oxide layers are believed to be essential to superconductivity, as they are common to the

Cuprate Superconductors [48] [49].

YBCO can be regarded as a derivative of 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂6 by oxidation, providing additional

𝑂2−

charge carriers. However, this process does not saturate the structure with additional

Oxygen, resulting in a number of vacancies in the lattice. The general chemical formula

of YBCO is therefore usually written as 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂7−𝛿, where – 𝛿 represents the Oxygen

defects in the structure. If 𝛿 > 0.65 the YBCO structure is tetragonal (due to the vacancies](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-15-320.jpg)

![15

in the Oxygen sites in the CuO layers), which is a form of YBCO which is insulating,

rather than superconducting [50] [51].

Figure 2.6.3: Image comparing the orthorhombic structure of 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂7 (left)

with the tetragonal structure of 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂6 (right) [50]

Superconductivity occurs in 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂7−𝛿 when 0 < 𝛿 < 0.65. As the dopant (Oxygen

content) increases from 𝛿 = 1, the hole concentration of the charge reservoir (CuO layers)

increases until a ‘threshold value’ is achieved (at 𝛿 ≈ 0.65), at which point positive charge

spills over to the 𝐶𝑢𝑂2 planes, which results in superconducting 𝐶𝑢𝑂2 planes [52]. The

current flows through these planes because the distance between the Copper atoms is

preferable to the distance between the Copper Oxide planes. A natural consequence of

this is that the current flow is dependent upon the crystal orientation, and performs best

when the current flows parallel to the 𝐶𝑢𝑂2 plane.

The occurrence of superconductivity in the YBCO structure is not well understood,

since no predictive theory is currently known. The evaluation of the superconducting

measurements is complicated (due to ambiguous reasons for superconductivity) [53]

although a range of theories have been put forward. Examples of these theories include

the application of the strong and weak coupling theories [54]. Also, more intensely

researched, is an adaptation of the phonon-based BCS-Eliashberg theory [55] [56] [57], in

which the original BCS theory is extended to include dynamic phonon exchange with

electron-phonon interactions as the principle cause for attractive interaction between

electrons [58]. However, Eliashberg and others haven’t considered this theory particularly

useful for discovering new High-Tc superconductors, as the theory doesn’t accurately

predict the normal state of superconductors. Interestingly, Bednorz and Müller (among

others) developed concepts describing strong electron-phonon coupling in metallic oxides

from various ideas, including the BCS theory [59] [60].

3. Experimental Method

The experimental side of the report comprised of three main objectives: observing

the Meissner effect in any of the YBCO samples; providing measurable evidence of

superconductivity e.g. readings of magnetic field variation around the samples and zero](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-16-320.jpg)

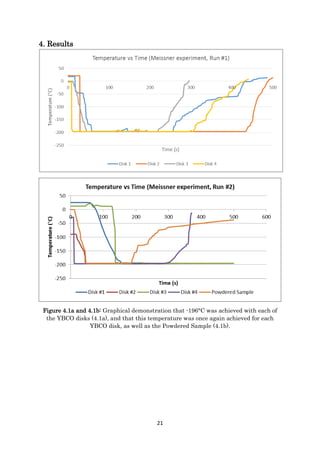

![23

Figures 4.3a, 4.3b and 4.3c: Graphical representation of magnetic field immediately

outside the YBCO sample) and temperature measurements vs time. Figure 4.3c

represents the experiment run without the YBCO disk present. The red circle in figure

4.3b will be discussed in chapter 5.

Figure 4.4: Graph demonstrating the dependence of the critical temperature of

𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂7−𝛿 on the oxygen defect 𝛿 [50].

Figures 4.5a and 4.5b: Graphs of orthogonal parameter lengths vs oxygen defects (and

stoichiometry) [61].

-40

-30

-20

-10

0

10

20

30

0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200

MangneticField(mT),Temperature(°C/10)

Time (s)

Manetic Field and Temperature vs Time (without disk)

Axial H Field Temperature Quad Temperature Pico Perpendicular H Field](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-24-320.jpg)

![24

Figure 4.6: Graph demonstrating the dependence of the structure of 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂7−𝛿 on the

occupancy of the O1 and O5 sites (located in the a – and b – axes, respectively) and the

oxygen deficiency [39].

Figure 4.7a: Literature XRD pattern of 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂7 from 20° to 60° [62].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-25-320.jpg)

![25

Figure 4.7b: XRD pattern of 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂7−𝛿 from 10° to 90° (annealed in 𝑂2 at 1153 K)

obtained from a paper on YBCO synthesis techniques [63].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-26-320.jpg)

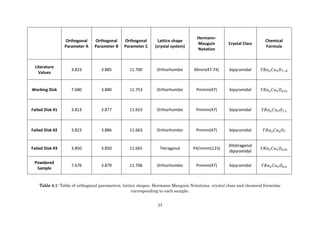

![31

sample. However, the a-axes of both WD and the powdered sample did not agree with

literature values of 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂7 (and therefore, the graphs). Bizarrely, the a-axis length

obtained from the experiment was exactly twice that of the literature value. Further

research into the crystalline structure of 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂6.5 indicated that the value of the a-

axis length obtained via X-Ray diffraction was not as peculiar as first thought, as it agreed

with the accepted literature value, demonstrated below in figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1: Diagram of 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂6.5 whereby the a-axis is twice the length of the b-axis

[50].

Figure 4.6 demonstrates the relationship between the occupancy of the O(1) and O(5) sites

and the Oxygen deficiency of the lattice; reference 50 states that neutron scattering

reveals that the Oxygen deficit is more prominent in the 𝐶𝑢𝑂4 square planes, rather than

the 𝐶𝑢𝑂5 pyramid planes. Although a literature search on this alternative site deficit was

unsuccessful, it may offer an explanation as to why the a-axis in 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂6.51 and

𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂6.5 is abnormally large (according to figure 4.5a, as this graph clearly states that

the a-axis is shorter than the b-axis for all Oxygen deficits for orthorhombic structures).

Regardless of the explanation, these orthogonal parameter lengths remain coherent with

those required for an orthorhombic lattice structure (𝑎 ≠ 𝑏 ≠ 𝑐).

A possible explanation for how these peculiar lattice parameter lengths allow

superconductivity in 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂6.51 and 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂6.5 is that YBCO structures with 𝛿 ≈ 0.5

have been known to possess ortho-II phases, whereby ortho-I denotes the normal

orthorhombic phase at 𝛿 = 0 and ortho-II denotes a structure of alternating Cu-O-Cu and

Cu-Cu chains in the basal plane. The possible significance of the ortho-II phase is that the

charge transfer from the 𝐶𝑢𝑂 to the 𝐶𝑢𝑂2 planes (discussed in chapter 2.6) take place only

if the ordered domains [64] (orthogonal parameters) are of an appropriate size. 𝐶𝑢𝑂2 planes

become superconducting if a significant amount of charge carriers are transferred from

the 𝐶𝑢𝑂 planes, which may only occur if the distance between Copper atoms in the 𝐶𝑢𝑂2

planes are preferable to the distance between 𝐶𝑢𝑂 planes. Perhaps the large a-axis

provides a situation in which the distance between Copper atoms is indeed preferable to

the distance between 𝐶𝑢𝑂2 planes in 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂6.51 and 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂6.5.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-32-320.jpg)

![32

5.5 Critical Temperature

This leads to the dependence of critical temperature on the Oxygen deficit of the

YBCO crystal lattice; Figure 4.4 is a plot of critical temperature as a function of Oxygen

defects. According to the graph, a superconducting sample of YBCO with 𝛿 = 0.49 or 𝛿 =

0.5 should have a critical temperature of approximately 56 K [64], which is far lower than

the critical temperature of the samples used in the experiment, which must have been at

least 77 K. Unfortunately an explanation for this peculiar outcome was not determined.

Research into the peculiar nature of the 58 K plateau yielded very interesting

theories; several experiments have shown [65] [66] [67] that there is an onset of 𝑇𝑐 > 0 for 𝛿 ≲

0.65, a plateau of 𝑇𝑐 ≈ 58 K for 0.35 ≲ 𝛿 ≲ 0.55 and a second plateau of 𝑇𝑐 ≈ 93 K for 𝛿 <

0.15. Beyond 𝛿 = 0.5 the critical temperature drops rapidly, reaching a value of 0 K at 𝛿 ≈

0.65. This range of compositions is comprised of broad superconducting transitions [61],

implying that the determination of the 0 K point is difficult. Jorgensen et al. suggests that

this may result from inhomogeneity in the samples, the severity of which increases with

higher Oxygen deficits. Poulsen et al. makes use of the anisotropic next-nearest-neighbour

lattice-gas (ASYNNNI) model together with the assumption that only minimal-size

clusters (MSCs) contribute to a charge transfer from the CuO planes by creating holes in

the 𝐶𝑢𝑂2 planes [68] (whereby holes are areas of positive charge). These clusters are

domains of coherent orthorhombic Oxygen orders of the ortho-I and ortho-II phases

mentioned above. The tendency of Oxygen atoms and vacancies to arrange themselves in

chains (rather than a random distribution across the lattice) leads to a varied Oxygen

order as a function of 𝛿, which implies that different orthorhombic symmetries occur at

different Oxygen deficits. Poulsen et al. suggests that the plateau observed between 𝛿 ≈

0.3 and 𝛿 ≈ 0.5 occurs due to a dynamic coexistence of both ortho-I and ortho-II

symmetries within these YBCO structures (perhaps in the form of a supercell) [61] [69].

5.6 Resistance

An attempt was made to measure the resistance across the working

superconducting disk; the experimental set-up involved Copper wires leading from a

multi-meter to the YBCO disk. Silver epoxy was applied to the disk’s surface as a

resistance-free substance for contact between the disk and the Copper wires, as is shown

in figure 5.2.

Figure 5.2: Image of Copper wires attached to WD using Silver epoxy (taped down, as

the Silver epoxy had recently dried and was still fragile).

The experiment was initially conducted with the disk at room temperature in order

to confirm that the set-up was working. Upon beginning the experiment it was found that](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-33-320.jpg)

![33

the multi-meter was unable to produce a reading of resistance, implying that the wires

had failed to make Ohmic contact with the disk. Research into this matter revealed that

the process was a non-trivial one [70], and also yielded a particularly useful paper on the

subject which stated several different attempts to measure resistance across an YBCO

sample e.g. the use of a Nickel-based circuit repair glue, and several attempts at using

Silver epoxy [48]. Some of the resistance measurements performed during Safranski’s

experiment showed positive results, whereby the resistance would drop drastically as the

critical temperature of the YBCO sample was reached (cooling from the normal state to

the Meissner state). However, upon heating the sample from the Meissner state, an

abrupt increase in resistance was not measured – it is unclear as to whether the

experimental set-up or the sample was the cause of this anomaly. Some of their

measurements failed to demonstrate superconductive properties at all, but by the time

these runs had been performed, Safranski suggests that their samples had developed a

thin semiconducting layer of YBCO on the surface. Several attempts were made to cure

Silver epoxy at various temperatures and periods of time, suggesting once more that this

type of experiment was non-trivial. Admittedly, this part of the experiment was

abandoned due to the previously mentioned difficulties. Alternatively, an adaptation of

Safranski’s results was performed to demonstrate expected resistance measurements for

a superconducting material passing from its normal state to the Meissner state, which is

displayed below in figure 5.3, whereby the temperature measurements have been changed

from those used by Safranski (the results were erroneous, and not appropriate for the

samples used in the experiments performed for this report).

Figure 5.3: Adaptation of resistance/temperature graphs from Safranski’s paper to

demonstrate expected results [48], based on the information provided in chapter 4,

namely 𝑇𝑐 ≈ 58 𝐾 for YBCO with 𝛿 ≈ 0.5.

Evidently from figure 5.3, the resistance drops significantly and abruptly as the critical

temperature is reached, which agrees with theoretical expectations discussed in the

introduction.

A method of improving the investigation of resistance versus temperature would

be to use a four-wire resistance set-up, whereby a known electrical current would be

passed through a superconducting disk (above its critical temperature) through two of the

wires. The remaining two wires would be attached to the disk between the two current](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-34-320.jpg)

![34

wires in order to measure the resistance (eliminating the resistance of the current wires).

The resistance would then be recorded as the temperature of the sample decreased below

its critical temperature. Additionally, a vacuum layer around the sample would increase

the accuracy of the temperature measurements (avoiding heat from the outside

environment interfering), which could also be applied to the Meissner and magnetic field

experiments. A layer of evaporated gold has also been suggested as a possibly reliable

method of achieving Ohmic contact [53].

5.7 Superconducting ring

As was briefly discussed in chapter 3, the powdered sample was intended for use

in a superconducting ring. The XRD results implied that the powdered sample was very

similar to that of WD, and that perhaps the powdered sample didn’t display any

superconductive properties during the Meissner experiments because it was insufficiently

compressed (whereby only sections of the sample would have become superconducting).

Upon further investigation, this superconductivity-related phenomenon was also

determined to be non-trivial, at which point it was realised that the appropriate

equipment for measuring minute changes in magnetic fields (namely SQUIDs) weren’t

readily available. Nevertheless, a literature search on the subject yielded two particularly

useful papers on the subject, both of which were particularly useful for chapter 2.5, one of

which outlines a sophisticated experiment on measuring the quantization of magnetic flux

within a superconducting ring system consisting of a high-temperature superconductor

(namely YBCO) connected to a low-temperature superconductor (namely Niobium) via

two ramp-type Josephson Junctions. The experiment involved the use of a SQUID to

measure minute changes in magnetic flux (induced by internal currents, which are

induced by an external, applied magnetic field) for 72 arrays of 0- and 𝜋- superconductor

rings, whereby 0- and 𝜋- indicate an increase (once induced) of an integer flux [𝑛Φ0] and

an increase of a half-integer flux [(𝑛 +

1

2

) Φ0], respectively. The experiment was also

performed in zero and non-zero background magnetic field environments, whereby the

Earth’s magnetic field was also accounted for. Bruel’s [39] measurements were positive

(with the exception of a few anomalies) and agreed with the expected results, which is

shown in figure 5.4.

Figure 5.4: Graph of measured values of magnetic flux (blue circles) in a 0-ring (without

a background magnetic field) compared with the expected steps in magnetic flux (solid

black lines) against an applied magnetic field [39].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-35-320.jpg)

![37

7. Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank Mr David Bradbury, my Lab Partner and friend, for his assistance

and patience during this report, and for his contribution to the plotted graphical data and

to figures 3.1 and 3.3. I am also grateful to Dr Dave Langstaff, Senior Experimental

Officer, for providing us with the required experimental apparatus, for his avidity to

helping with the Meissner experiments and for his suggestions of how to overcome some

of the experimental obstacles that were encountered.

I’d also like to thank Dr Martin Wilding, Senior Lecturer and our Project

Supervisor, for his guidance, especially on the YBCO structure and the significance of

Oxygen defects, and for his encouraging nudges in the right direction in terms of research

required for this report.

8. References

[1] M. Neeraj; Applied Physics for Engineers; PHI Lerning Private Ltd.; pp. 931, 19.2;

ISBN – 8120342429 (2011)

[2] P.J. Ford, G.A. Saunders; The Rise of the Superconductors; 1, 5; CRP Press; ISBN

9780748407729 (2004)

[3] H. K. Onnes; Akad. van Wetenschappen (Amsterdam); Vol. 14, pp. 113, 818 (1911)

[4] Blakemore, J.S.; Solid State Physics (Second Edition); Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge; pp 266, 3.6; ISBN – 0-521-30932-8 (1985)

[5] D. Saint-James, G. Sarma, E. J. Thomas; Type II superconductivity; Pergamon Press;

Headington Hill, Oxford; 13-14, 1.7; ISBN 00801239299780080123929 (1969)

[6] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yttrium_barium_copper_oxide

[7] M. Tinkham, Introduction to superconductivity, 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill, (1996)

[8] W. Meissner, R. Ochsenfeld; Ein Neuer Effekt bei Eintritt der Supraleitfähigkeit,

Naturwissenschaften, Vol. 21, pp. 787-788 (1933)

[9] A. D. C. Grassie; The Superconducting State; 5, 1.2; Sussex University Press, Sussex;

ISBN 0856210145 (1975)

[10] Edward M. Purcell, David J. Morin; Electricity and Magnetism (Third Edition);

Harvard University, Massachusetts; Cambridge University Press; 197, 4.4; ISBN 978-1-

107-01402-2 (2013)

[11] T. Van Duzer, C. W. Turner; Principles of Superconductive Devices and Circuits; 31-

35, 1.10; ISBN 0-7131-3432-1 (1981)

[12] J. E. Hirsch; Dynamic Hubbard model: kinetic energy driven charge expulsion, charge

inhomogeneity, hole superconductivity and Meissner effect; 9, 12; Institute of Physics

Publishing; Phys. Scr. 88, 035704 (16pp) (2013)

[13] A. Durrant; Quantum Physics of Matter; Institute of Physics Publishing, London;

ISBN 0750307218 (2000)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-38-320.jpg)

![38

[14] Michael Tinkham; Introduction to Superconductivity (Second Edition); McGraw-Hill

Book Co., New York; ISBN-13: 978-0-486-43503-9 (1996)

[15] Kittel, Charles; Introduction to Solid State Physics; John Wiley & Sons; pp. 273–

276; ISBN 978-0-471-41526-8 (2004)

[16] L. P. Gor’kov; Microscopic Derivation of the Ginzburg-Landau equations in the

Theory of Superconductivity; Soviet Physics JETP, Vol. 36 (9), No. 6; Institute of Physical

Problems, Academy of Sciences, U.S.S.R. (1959)

[17] P. C. Hohenberg, A. P. Krekhov; An introduction to the Ginzburg-Landau theory of

phase transitions and nonequilibrium patters; 23, 7 (2014).

- A link to reference 17: http://physics.nyu.edu/~pch2/GL_theory-submitOct13-

2014.pdf

[18] A. D. C. Grassie; The Superconducting State; 49, 3.1; Sussex University Press,

Sussex; ISBN 0856210145 (1975)

[19] V. L. Ginzburg; On the Superconductivity and Superfluidity (Nobel Lecture); P. N.

Lebedev Physics Institute, Moscow (2003)

[20] A. D. C. Grassie; The Superconducting State; 51, 3.1; Sussex University Press,

Sussex; ISBN 0856210145 (1975)

[21] V. L. Ginzburg; On the Theory of Superconductivity; Il Nuovo Cimento, Vol. 11, N. 6;

P. N. Lebedev Physics Institute, Moscow (1955)

[22] Lecture Notes on the Ginzburg-Landau Theory at Cambridge University,

Cambridge

A link to reference 22: http://www.qm.phy.cam.ac.uk/teaching/lecture_2_12.pdf

[23] F. London; On the Problem of the Molecular Theory of Superconductivity; Phys. Rev.

74, 562 (1948)

[24] A. A. Abrikosov; Type II Superconductors and the Vortex Lattice (Nobel Lecture);

Material Science Division, Argonne National Laboratory, USA (2003)

[25] Blakemore, J.S.; Solid State Physics (Second Edition); Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge; pp 277-288, 3.6; ISBN – 0-521-30932-8 (1985)

[26] H. Fröhlich; Theory of the Superconducting State. I. The Ground State at the

Absolute Zero of Temperature; Phys. Rev. Vol. 79, 3 (1950)

[27] C. A. Reynolds, B. Serin, W. H. Wright, L. B. Nesbitt; Superconductivity of Isotopes

of Mercury; Phys. Rev. 78, 487 (1950)

[28] E. Maxwell; Isotope Effect in the Superconductivity of Mercury; Phys. Rev. 78, 477

(1950)

[29] J. Bardeen; Electron-Phonon Interactions and Superconductivity (Nobel Lecture);

Department of Physics and of Electrical Engineering, University of Illinois, Urbana,

Illinois (1972)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-39-320.jpg)

![39

[30] A. D. C. Grassie; The Superconducting State; 27, 2.2; Sussex University Press,

Sussex; ISBN 0856210145 (1975)

[31] J. Bardeen, L. N. Cooper, J. R. Schrieffer; Theory of Superconductivity; Phys. Rev.

Vol. 108, 5 (1957)

[32] L. N. Cooper; Bound Electron Pairs in a Degenerate Fermi Gas; Phys. Rev. Vol. 104,

4 (1956)

[33] D. Saint-James, G. Sarma, E. J. Thomas; Type II superconductivity; Pergamon Press;

Headington Hill, Oxford; 44-45, 3.3; ISBN 00801239299780080123929 (1969)

[34] R. Doll, M. Näbauer; Experimental Proof of Magnetic Flux Quantization in a

Superconducting Ring; Phys. Rev. Lett 7, 52 (1961)

[35] F. London; Superfluids, Vol 1, Macroscopic Theory of Superconductivity; John Wiley

& Sons, Inc., London (1950)

[36] L. I. Schiff; Quantum Mechanics (third edition); 31, 2; McGraw Hill, New York (1968)

[37] S. Gasiorowicz, Quantum Physics, 3rd ed., John Wiley and Sons, Inc., (2003)

[38] R. Bruel, A. Timmermans; Magnetic Flux Quanta in High-Tc/Low-Tc Superconducting

Rings with π-phase-shifts (Bachelor Thesis); University of Twente (2013)

[39] A. D. C. Grassie; The Superconducting State; 70, 3.7; Sussex University Press,

Sussex; ISBN 0856210145 (1975)

[40] G. van der Steenhoven et al.; Fractional Flux Quanta in High- 𝑇𝑐/Low- 𝑇𝑐

Superconducting Structures, Ph.D. Thesis, University of Twente; Gildeprint

Drukkerijen; ISBN 978-90-9024316-0; C.J.M. Verwijs (2009)

[41] L. Onsager; Magnetic Flux through a Superconducting Ring; Phys. Rev. Lett. 7, 50

(1961)

[42] B. S. Deaver, W. M. Fairbank; Experimental Evidence for Quantized Flux in

Superconducting Cylinders; Phys. Rev. Lett. 7, 43 (1961)

[43] H. Wenk, A. Bulakh; Minerals: Their Constitution and Origin; New York, NY:

Cambridge University Press; ISBN 978-0-521-52958-7 (2004)

[44] M. T. Dove; Structure and Dynamics (An Atomic View Of Materials); 35-37, 2.4.1;

Oxford University Press; ISBN 978-0-19-850677-5 (2003)

[45] A. M. GGlazer; Simple Ways of Determining Perovskite Structures; 35-37, 2.4.1; Acta

Cryst. A31, 756 (1975)

[46] D. M. Buitrago, N. C. Reyes-Suarez, J. P. Peña, O. Ortiz-Diaz, J. Otálora, C. A. Parra

Vargas; High Temperature Superconductivity on the New Superconductor System

𝑌𝑏1.8 𝑆𝑚1.2 𝐵𝑎5 𝐶𝑢8 𝑂18; J. Supercond Nov Magn, 26:2269-2271; Springer Science+Business

Media (2013)

[47] Crystal Structure of YBCO; Hoffman Lab; Harvard University;

http://hoffman.physics.harvard.edu/materials/Cuprates.php](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-40-320.jpg)

![40

[48] Chris Safranski; Resistance of the Superconducting Material YBCO; Senior Project

presented to The Faculty of the Department of Physics, California Polytechnic State

University, California (2010)

[49] K. A. Miller; The Unique Properties of Superconductivity in Cuprates; J Supercond

Nov Magn 27:2163-2179; Springer Science+Business Media (2014)

[50] A. K. Saxena; High-Temperature Superconductors: Crystal Structure of High

Temperature Superconductors; 2, 224; Springer Series in Material Science; ISBN 978-3-

642-00711-8 (2010)

[51] Small article on YBCO. Unfortunately, no author was available

- Link to reference [53]; http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/rzepa/mim/century/html/ybco.htm

[52] D. Varshney, G. S. Patel, S. Shah, R. K. Singh; Pairing mechanism and

superconducting state parameters in 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂𝛿; Indian Journal of Pure and Applied

Physics, Vol. 39, pp. 246-258 (2001)

[53] I. Kirschner, J. Bánkuti, M. Gál, K. Torkos, K. G. Sólymos, G. Horváth; High-Tc

Superconductivity in La-Ba-Cu-O and Y-Ba-Cu-O Compounds; Europhys. Lett., 3 (12), pp.

1309-1314 (1987)

[54] V. Z. Kresin, S. A. Wolf, H. Morawitz; Mechanisms of conventional and high-Tc

superconductivity; Oxford University Press, New York (1993)

[55] J. Bardeen, L. N. Cooper, J. R. Schrieffer; Microscopic Theory of Superconductivity;

Phys Rev. 106, Sov Phyics JETP. 11 (1960)

[56] A. Lanzara, P. V. Bogdanov, X. J. Zhou, S. A. Kellar, D. L. Feng, E. D. Lu, T. Yoshida,

H. Eisaki, A. Fujimori, K. Kishio, J.-I. Shimoyama, T. Noda, S. Uchida, Z. Hussain & Z.-

X. Shen; Evidence for ubiquitous strong electron–phonon coupling in high-temperature

superconductors; Nature 412, 510-514 (2001)

[57] L. K. Miodrag; Importance of the Electron–Phonon Interaction with the Forward

Scattering Peak for Superconducting Pairing in Cuprates; Journal of Superconductivity

and Novel Magnetism, Vol. 19, Nos. 3-5 : Springer Science + Business Media, Inc (2006)

[58] F. Marsiglio, J. P. Carbotte; Electron-Phonon Superconductivity; Cornell University

Library (2008)

[59] J. G. Bednorz, K. A. Müller; Possible High Tc Superconductivity in the La-La-Cu-O

System; Z Phys. B – Condensed Matter 64, 189-193 (1986)

[60] J. G. Bednorz, K. A. Müller; Perovskite-type oxides – The new approach to high-Tc

superconductivity; Review of Modern Physics, Vol. 60, No. 3 (1988)

[61] J. D. Jorgensen et al.; Structural properties of oxygen-deficient 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂7−𝛿; Phys.

Rev. B, Vol 43, 4 (1989)

[62] S. Davison et al.; Chemical problems associated with the preparation and

characterization of superconducting oxides containing copper; Chemistry of high-

temperature superconductors, American Chemical Society p. 65-78 (1987)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-41-320.jpg)

![41

[63] X. L. Xu, J. D. Guo, Y. Z. Wang, A. Sozzi; Synthesis of nanoscale superconducting

YBCO by a novel technique; Physica C 371, 129-132 (2002)

[64] T Zeiske et al.; On the Structure of the Superconducting Ortho-II Phase of

𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂6.51; Journal of Electronic Materials, Vol. 22, No. 10 (1993)

[65] R. J. Cava, et al.; Superconductivity in Multiple Phase Sr2Ln1–xCaxGaCu2O7 and

Characterization of La2–xSrxCaCu2O6+δ; Physica C. 185-189, p. 180-183

[66] R. J. Cava, et al.; STRUCTURAL ANOMALIES, OXYGEN ORDERING AND

SUPERCONDUCTIVITY IN OXYGEN DEFICIENT Ba2YCu3Ox; Physica C. 165, 419-

433 (1990)

[67] V. I. Simonov; Atomic Structure and Physical Properties of Crystals; Institute of

Crystallography, USSR Acad. Sci., Moscow [Butll. Soc. Cat . Cien.], Vol. XII, Num. 2

(1991)

[68] J. D. Jorgensen et al.; Oxygen ordering and the orthorhombic-to-tetragonal phase

transition in YBa2Cu3O7-x; Phys Rev B, Vol. 36, 7 (1987)

[69] R. Beyers et al. Oxygen ordering, phase separation and the 60-K and 90-K plateaus

in 𝑌𝐵𝑎2 𝐶𝑢3 𝑂𝑥; Nature 340, 619-621 (1989)

[70] J. W. Ekin; Ohmic Contacts to High- 𝑇𝑐 Superconductors; Proc. SPIE 1187, Processing

of Films for High Tc Superconducting Electronics, 359 (1990)

9. Literature Review

High Temperature Superconductivity

1. Introduction

The project is a study of the nature of superconductive materials.

Superconductivity is a quantum mechanical phenomenon of the expulsion of the magnetic

field from the material, and the state in which the material has zero electrical DC

resistance. This occurs when the material is cooled to very low temperatures (below the

characteristic critical temperature of the particular material).

Superconductivity was first observed in 1911 by Dutch physicist Heike

Kamerlingh Onnes. While cooling a solid mercury wire to approximately 4 Kelvin (-2690C)

using Liquid helium, Onnes observed that the resistance in the wire disappeared very

suddenly. Onnes’ work earned him the Nobel Prize in physics just two years later. The

next milestone in understanding how matter behaves at these extreme temperatures

occurred in 1933; German physicists Walther Meissner and Robert Ochsenfeld discovered

superconducting materials repel magnetic fields. It was observed that the currents

induced in the superconductor exactly mirror the external magnetic field, which would

otherwise have penetrated the material. The phenomenon is known as strong

diamagnetism but is today often referred to as the “Meissner Effect.” This effect is

sufficiently strong to levitate a magnet over a superconducting material (in the

superconducting state).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-42-320.jpg)

![42

Fritz and Heinz London explained the Meissner Effect in 1935 with (what are now

known as) the London equations, stating that the effect occurred due to a minimization of

electromagnetic free energy carried by superconducting current. In 1950, Vitaly Ginzburg

and Lev Landau devised what is known today as the Ginzburg-Landau theory. The theory

had great success explaining the macroscopic properties of a superconductor, and also

provided categories in which superconductors may be divided into i.e. Type I and II. 1957

saw perhaps the most important theory for superconductivity, the Bardeen Cooper

Schrieffer (BCS) theory. Developed by John Bardeen, Leon Cooper and John Robert

Schrieffer, the theory gives a complete microscopic explanation of superconductivity and

describes the superconducting current as a superfluid of Cooper pairs (pairs of electrons)

that are interacting with phonons, which earned them the Nobel Prize in physics in 1972.

Since the discovery of superconductivity there have been numerous metals and alloys that

have displayed the phenomenon, but all at very low temperatures. In 1986 however, Georg

Bednorz and Karl Alexander Mueller discovered superconductivity in a lanthanum-based

cuprate perovskite material at 35K. This clearly differed from the critical temperature of

conventional superconducting materials; the discovery began an age of ceramic

superconductor production with much higher critical temperatures (which the BCS theory

cannot fully explain). These transition temperatures have increased to greater than that

of the boiling point of liquid nitrogen, meaning that experimentally it is much easier to

demonstrate superconductivity. Further research has seen superconductivity in organic

materials such as fullerenes and ever increasing transition temperatures in new

materials. In 2014 the phenomenon was observed at room temperature [1] (albeit for a

millionth of a second).

Figure 1.1: Image of a magnet levitating over a superconductor [2].

There are several useful applications for superconductivity; in transport, the

magnetic levitation can be used for vehicles such as trains, which float above the tracks.

The advantage of this method rather than conventional electromagnets is that there is no

energy lost as heat due to an absence of friction between the train and the tracks. The

most well-known example of this method of transport is the MAGLEV train in Japan,

which can reach speeds of up to 361 miles per hour. Another very important use for

superconductors is MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scanners. Inside the scanner, the

human body is subjected to a strong superconductor-derived magnetic field which forces

hydrogen atoms in the water and fat molecules to accept energy. This energy is then

released and a computer can detect this energy at a certain frequency and display the

results graphically. Superconducting magnets are used in the CERN Large Hadron

Collider which makes the acceleration of sub-atomic particles to near light speed possible.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-43-320.jpg)

![43

Figure 1.2: Image of a brain scan produced by a MRI scanner [3].

We will discuss the nature of superconductivity in a material known as Yttrium Barium

Copper Oxide; a material with a perovskite-like structure that displays High-temperature

superconductivity. During this experiment, we will attempt to address three major

questions on the nature of high temperature superconductivity (SC), and SC in general:

An attempt will be made to demonstrate and explain the Meissner effect in our sample

of YBCO; The Meissner effect being the spontaneous expulsion of a superconducting

material’s magnetic field as the material’s temperature is reduced below its critical

temperature (while exposed to a weak magnetic field). The material becomes perfectly

diamagnetic, which cancels all magnetic flux within the material – the material never

has an internal flux density, even when placed within an applied magnetic field. [4]

The effect will be discussed in more detail in the theory section of this review.. If the

Meissner effect occurs, it will be apparent; a magnet will be placed above the

superconducting material – if it floats above the material, then the material has

expelled all of its magnetic field.

An attempt will be made to explain how defects within the YBCO structure

affect/determine the superconductive properties of the material below the critical

temperature. The first step in achieving an understanding of this is to produce a three-

dimensional picture of the density of electrons (from which we can determine the

structure and its defects) by means of X-ray Diffraction; the picture of an YBCO

sample with defects will be compared with that of an YBCO sample without defects.

The superconductive properties of both samples will be examined, and the data

obtained will be analysed in an attempt to determine how Oxygen defects affect

superconductivity.

An attempt will be made to demonstrate zero resistance within the YBCO sample, and

to explain why it arises. This will be done by placing probes within the copper block,

which will read the resistance of the material. This characteristic will be discussed in

the theory section.

An attempt will be made to determine if current flux is quantized; this will be done by

producing a superconducting ring system for a powdered sample of YBCO. The ring

will be subject to an external magnetic field while below its critical temperature. An

increase in the external magnetic field should result in an increase in magnet flux in

quantized steps.

2. Theory

2.1. Superconductors](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-44-320.jpg)

![44

Superconductors are materials that lose all resistance to the flow of electric current

when their temperature is dropped below their critical temperature. Besides achieving

zero resistance below their critical temperature, superconductors gain other magnetic and

electrical properties, such as zero resistivity; if the resistivity drops to 0, then the

resistance of the material will also drop to zero, which gives rise to the existence of

permanent currents. [5] Another example superconductive material properties is a sudden

change in magnetic susceptibility from a paramagnetic value to -1, meaning the material

has become perfectly diamagnetic. Diamagnetic materials are materials that create and

induced magnetic field in the opposite direction of an external magnetic field, which

causes a repulsion effect. This is known as the Meissner effect. Both of these properties

will be discussed and demonstrated during the experiment.

Figure 2.1.1: diagram demonstrating the exclusion of a magnetic field (represented as

arrows) from a superconducting material below the critical temperature [6].

Figure 2.1.2: diagram representing the sharp drop in resistance (due to the drop in

resistivity) of a superconductor at the critical temperature, compared to a non-

superconducting material [7].

2.1.1. Types of Superconductors

There are several methods of classifying superconductors. One such example is

how the material responds to a magnetic field; if the magnitude of an external magnetic](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-45-320.jpg)

![45

field is increased beyond the critical point (which is dependent upon the material) the

magnetic flux penetrates the material. The material will thus undergo a phase transition

from a superconducting state to a normal state.

In Type I superconducting materials, the material continues to expel magnetic flux

until the magnetic field exceeds the critical point (Hc). At which point, the material

abruptly switches from a Meissner state to a normal state. Type I superconductors are

usually pure materials.

Type II semiconducting materials act as type I superconductors in a weaker

magnetic field than that of the material’s critical field. If the external magnetic field is

increased above the critical point (Hc1), then the material transitions into the ‘mixed-

state’, which is a state of partial penetration of magnetic flux. By further increasing the

magnetic field, the flux penetration of the material will increase to a maximum at upper

field strength (Hc2), whereby the material transitions to the normal state. Type II

superconductors are usually alloys.

Figure 2.1.3: Image of the critical magnetic field strengths of type I and type II

superconductors, where the larger triangle represents the abrupt switch from the

Meissner state to the normal state of type I, and the smaller triangle represents the

transition to the vortex state of type II [8a].

2.1.2. High Temperature Superconductors

Superconductors may also be categorised by their critical temperature; low-

temperature superconductivity and high-temperature superconductivity, which are

materials that transition to the superconductive state below and above 30 K, respectively.

The benefit of high-temperature superconductors is that liquid nitrogen can be used as a

coolant. YBCO is an example of a high-temperature superconductive material, and the

importance of the perovskite structure to superconductivity will be discussed further in

the theory section. High-temperature superconductivity is not fully understood; there is

no theory that is generally accepted to sufficiently explain high-temperature (HT)

superconductivity. Many scientists believe that the coupling between electrons and

phonons (or lattice vibrations) induces electron pairing within HT superconductors, but

there is a lack of direct evidence. [9]

2.2. Meissner Effect

The Meissner effect is a phenomenon whereby the magnetic field of a

superconductor gets expelled as it transitions into the superconducting state. Nearly all

the magnetic flux is expelled from a superconductor in a weak, applied magnetic field.

Electric currents form near the surface and the magnetic field of these surface currents

cancels the weak applied field. The expulsion of the field doesn’t change with time,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-46-320.jpg)

![46

therefore the currents are persistent. The Meissner effect cannot be explained by infinite

conductivity alone; a concise explanation was first given by the London equations.

Superconductors that experience the Meissner effect exhibit super diamagnetism.

This means that the total magnetic field deep inside the material is zero, and that their

magnetic susceptibility, =-1. In superconductors the origins of the diamagnetism is

different to what is observed in normal materials. In a superconductor, an illusion of

perfect diamagnetism is seen from the persistent currents on the surface which oppose

the applied field.

The original paper [10] by Meissner and Ochsenfeld is in German which is of little

use to us, but there is plenty of literature on the Meissner effect. The book Introduction

to Solid State Physics [11] by Charles Kittel gives a thorough description of the Meissner

effect (and other theories relating to superconductivity).

2.3. London Equation

The London equation shows the relationship between electromagnetic fields and current,

in and around a superconductor.

𝒋 𝒔 = −

𝑛 𝑠 𝑒2

𝑚𝑐

𝑨

Whereby js is superconducting current density, e is the charge of an electron and proton, m

is the electron mass, ns is a constant associated with a number density of superconducting

carriers, and A is the vector potential (introduced by the London brothers).

Also predicted was a characteristic length scale, λ;

∇2

𝑩 =

1

𝜆2

𝑩

Whereby

𝜆 ≡ √

𝑚𝑐2

4𝜋𝑛 𝑠 𝑒2

𝜆 is known as the London penetration depth. This shows that the magnetic field inside

the superconductor decays exponentially. The London penetration depth varies depending

on the material. The Electromagnetic Equations of the Supraconductor [12] by F. and H.

London gives a very detailed derivation of the London equation and how it explains the

Meissner effect, while High Temperature Superconductivity [13] by Gerald Burns gives a

more concise derivation, which is much easier to grasp. The book also gives an excellent

overview of many aspects that this literature review covers.

2.4. Ginzburg-Landau Theory

The Ginzburg-Landau theory is a mathematical physical theory used to describe

superconductivity. It postulated a model to describe type I superconductors without

looking at the microscopic properties.

The Ginzburg-Landau theory predicted new characteristic lengths in a superconductor.

The first is called the coherence length, represented by the symbol, ξ. For a temperature](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b4ea8689-994b-41de-96b1-3f4ce4a8c65e-170201232749/85/Project-Report-47-320.jpg)

![47

greater than the critical temperature of the superconductor, the coherence length is given

by;

For a temperature below the critical temperature, the coherence length is given by;

The second characteristic length is the penetration depth; previously show with

the London equations. The equation below shows the penetration depth (λ) in terms of the

Ginzburg-Landau model;

The Ginzburg-Landau parameter “k” is the ratio between penetration depth and

coherence length (λ/ξ). Type 1 super conductors have a k value between 0 and 1/√2 and

type 2 superconductors have a k value greater than 1/√2. The Superconducting State [14]

by A.D.C. Grassie goes into great detail with the Ginzburg Landau theory, its equation,

and relationship with coherence length and penetration depth. The mathematical side of

the theory is very complicated and perhaps goes into too much depth for our experiment.

2.5. BCS Theory

BCS theory was the first microscopic theory of superconductivity. The microscopic

effect is the condensation of Cooper pairs into a boson-like state. A Cooper pair is a pair

of electrons which are bound together in a certain way at low temperatures. There is an

arbitrarily small attraction between electrons that can create a paired state which has

energy below that of the Fermi energy, which implies that they are bound. In

superconductors the attraction is caused by the electron-phonon interaction. The energy

of the pairing interaction is around the order of 10-3eV and these pairs can break with

thermal energy, so there are a significant number of electrons in Cooper pairs at low

temperatures. Materials with heavier ions have lower transitioning temperatures. The

theory of Cooper pairing explains this; heavier ions are harder to move and less able to

attract electrons, giving a smaller binding energy. If the temperature is low enough,

electrons become unstable against forming into Cooper pair near the Fermi surface. The

binding occurs in an attractive potential, no matter how weak. In superconductor the

attraction is usually due to an electron-lattice interaction. The BCS theory itself doesn’t

require an origin of the potential, only that it is attractive.

The electron-phonon interaction in many superconductors arises from an electron

moving through a conductor, attracting nearby positive charges in the lattice. The lattice

deforms and causes another electron with opposite spin to move into the region of higher

positive charge density. The two electrons then become pairs, and in a superconductor,

there are a great number of these pairs. These pairs overlap and form a condensate; the

condensed state means that breaking one of the pairs would affect the entire condensate.