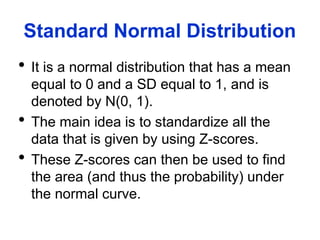

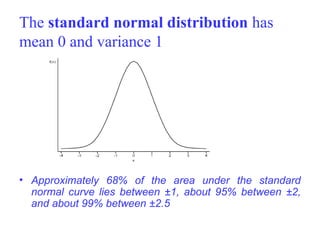

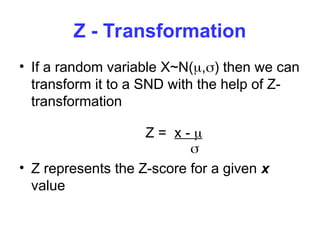

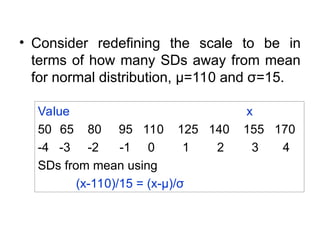

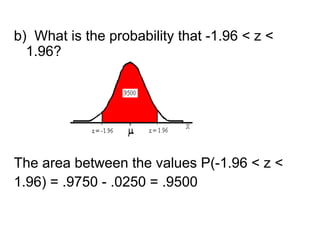

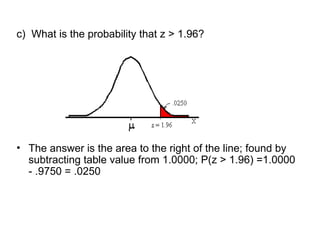

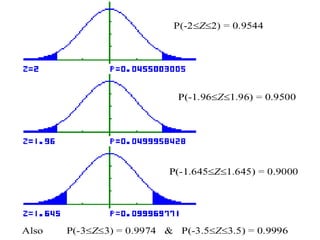

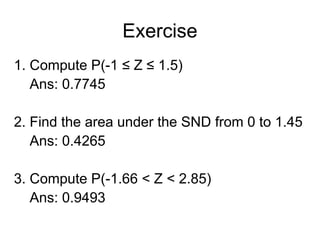

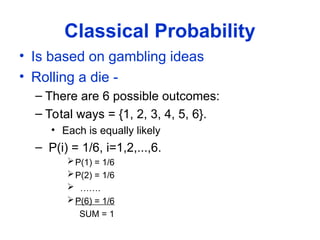

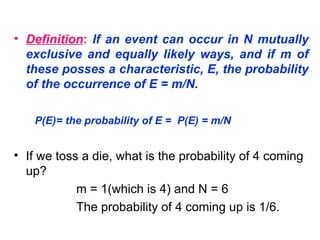

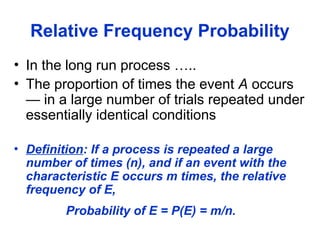

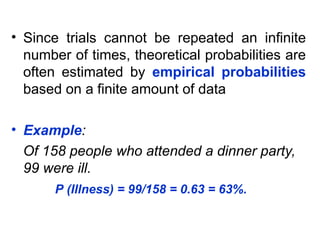

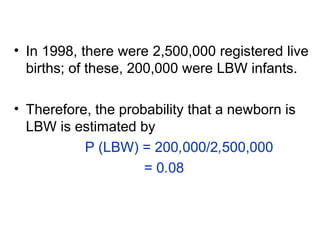

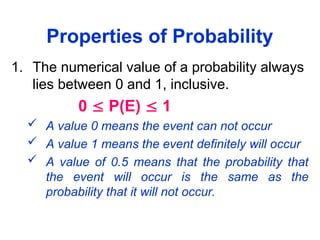

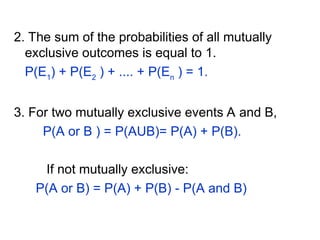

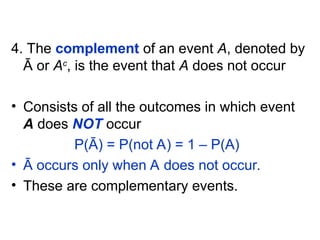

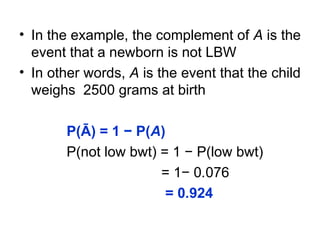

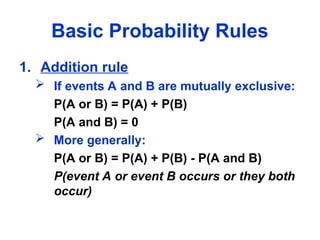

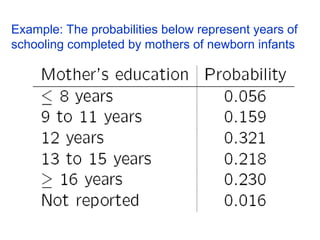

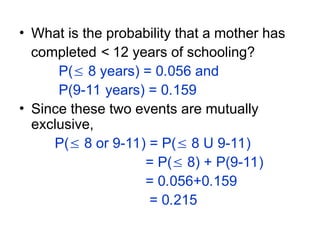

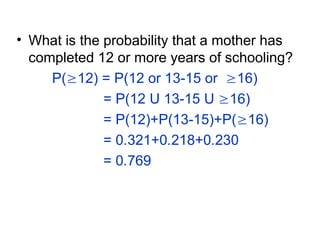

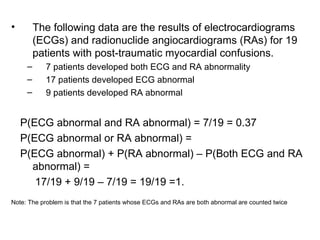

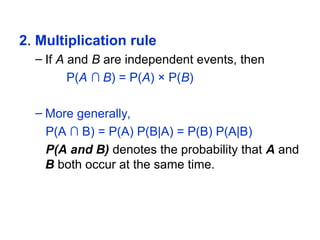

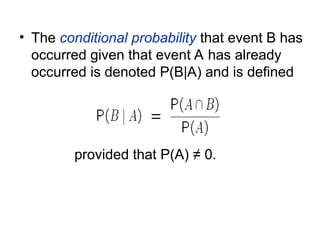

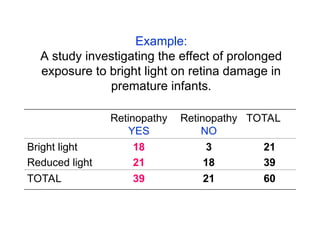

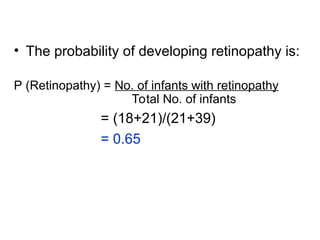

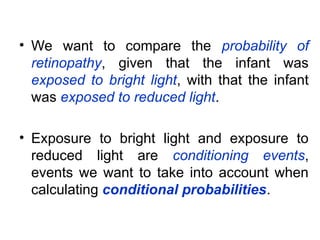

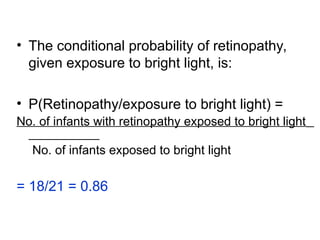

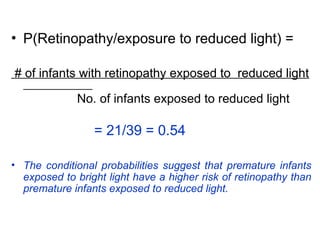

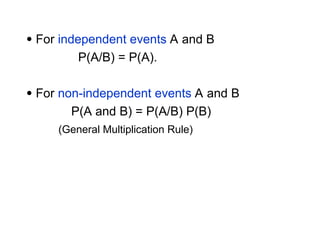

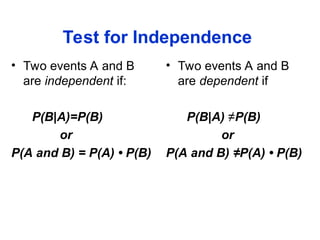

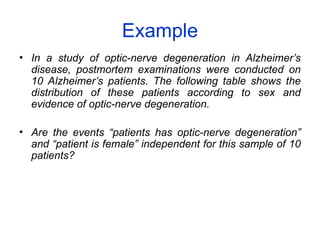

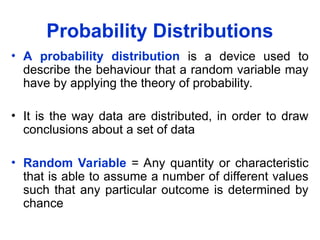

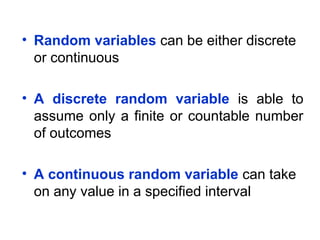

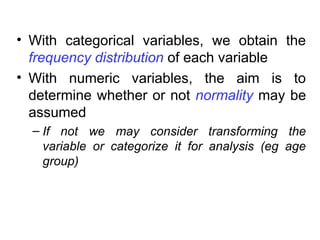

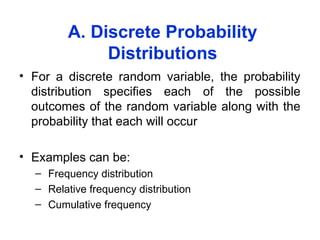

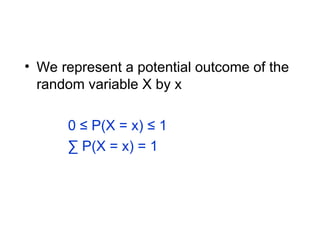

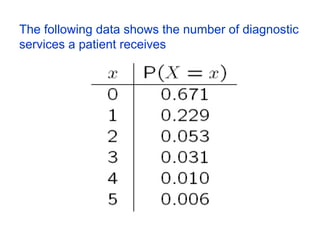

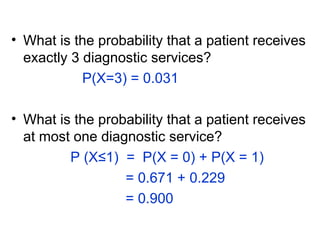

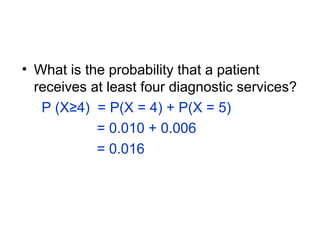

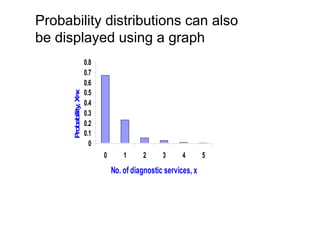

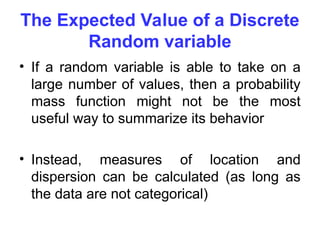

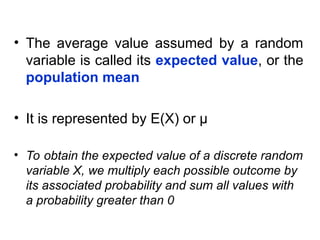

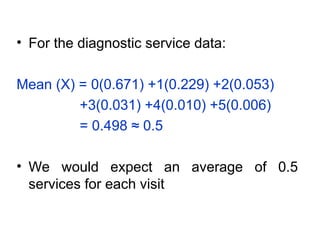

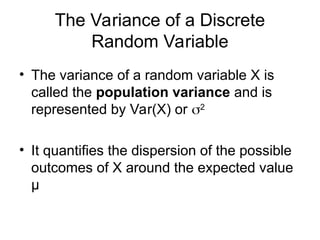

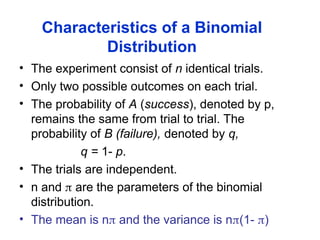

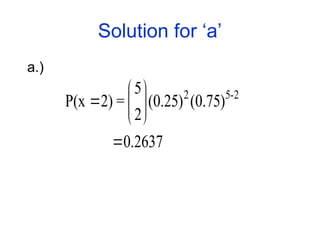

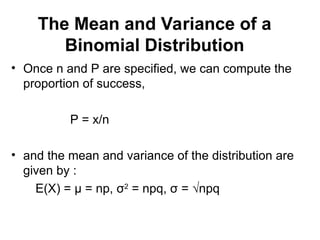

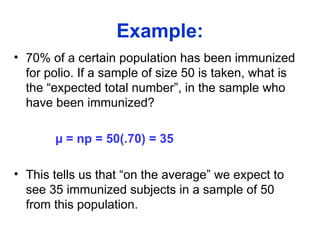

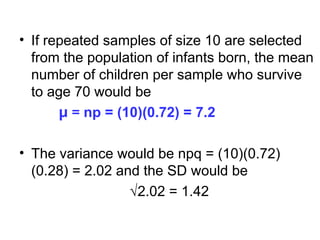

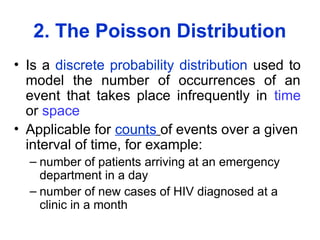

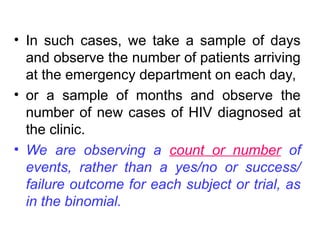

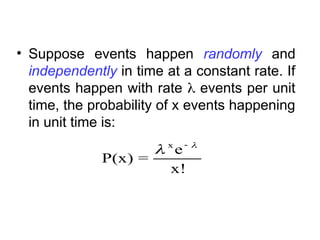

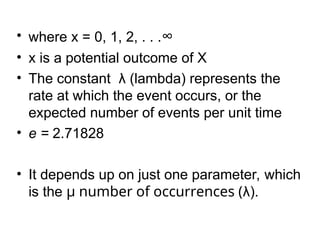

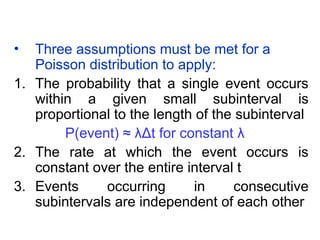

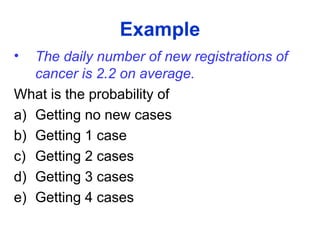

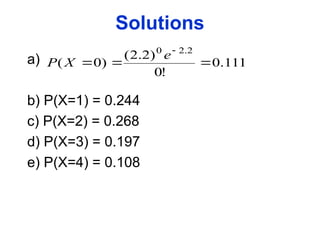

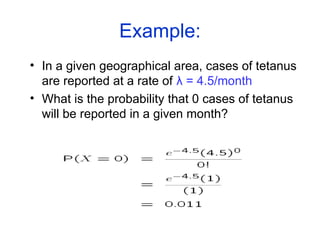

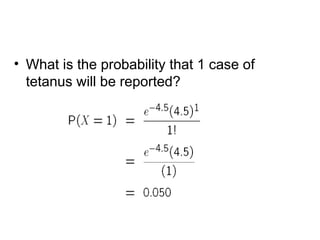

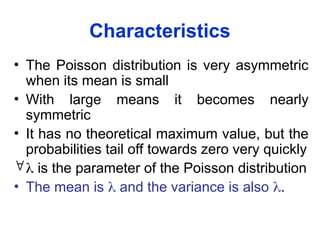

The document explains the fundamentals of probability and its distributions, highlighting its significance in both statistics and medicine. It covers concepts like objective and subjective probabilities, events, and the rules governing probability calculations, including independence and dependence of events. Additionally, it discusses the application of probability distributions in analyzing data and drawing conclusions from random variables.

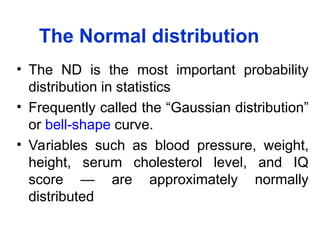

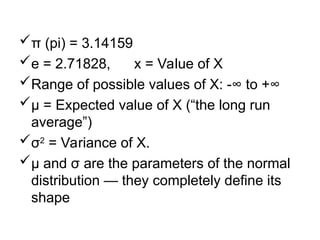

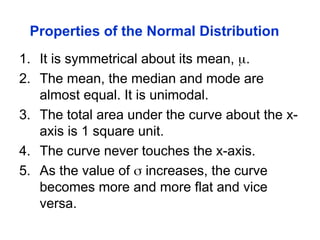

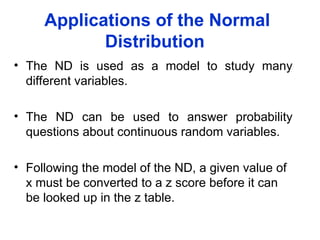

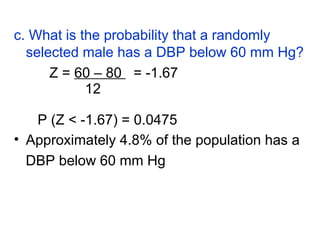

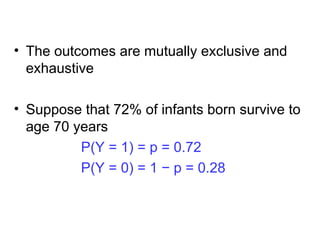

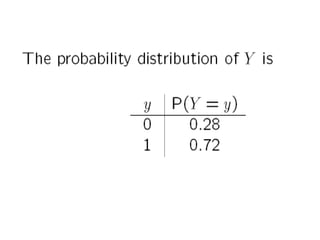

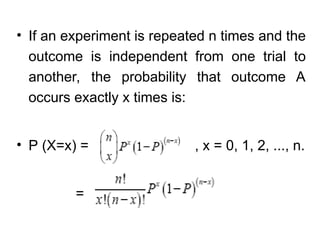

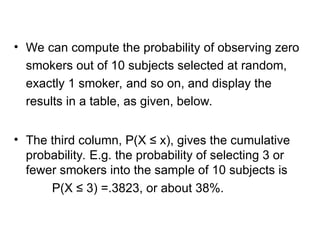

![A binomial probability distribution occurs when

the following requirements are met.

1. The procedure has a fixed number of trials.

2. The trials must be independent.

3. Each trial must have all outcomes that fall

into two categories.

4. The probabilities must remain constant for

each trial [P(success) = p].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4probabilityandprobabilitydistn-241215172104-5e205202/85/Probability-and-probability-distribution-ppt-72-320.jpg)

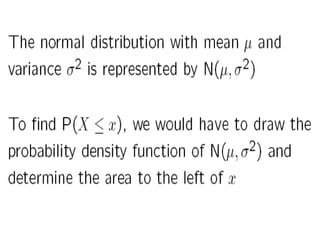

![• We calculate:

Pr [ a < X < b], the probability of an

interval of values of X.

• For the above reason,

• is also without meaning.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4probabilityandprobabilitydistn-241215172104-5e205202/85/Probability-and-probability-distribution-ppt-102-320.jpg)