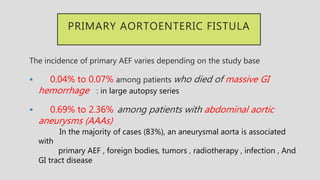

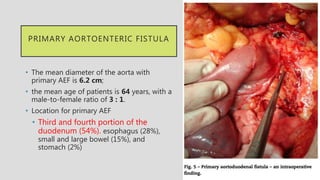

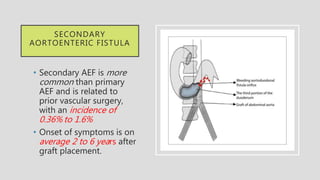

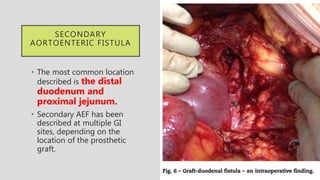

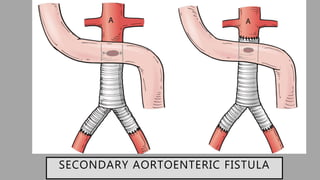

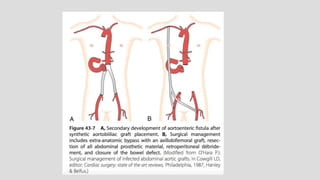

1. Aortoenteric fistula (AEF) is a communication between the aorta and gastrointestinal tract that can be primary, between the native aorta and GI tract, or secondary, between a reconstructed aorta and GI tract.

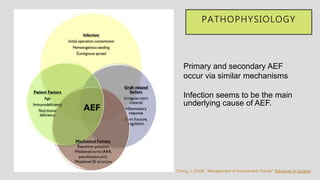

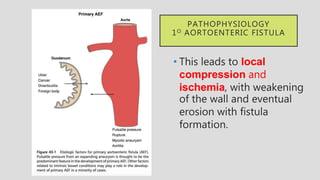

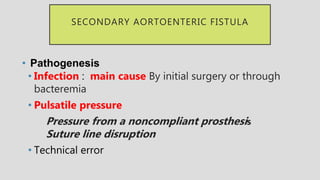

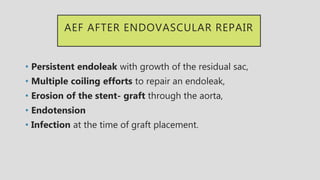

2. Infection is the main cause of both primary and secondary AEF, leading to local compression, ischemia and erosion of the aortic wall.

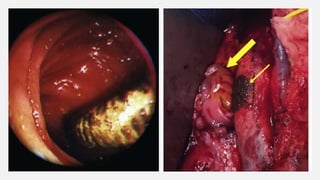

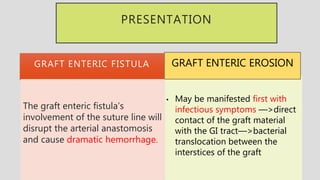

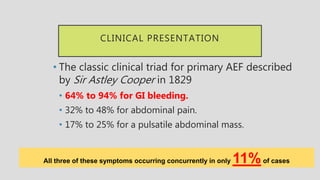

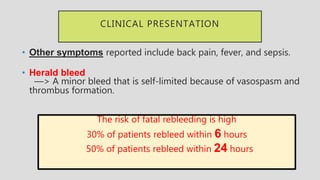

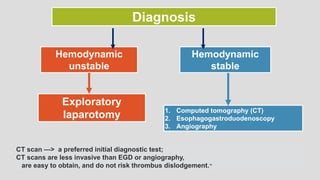

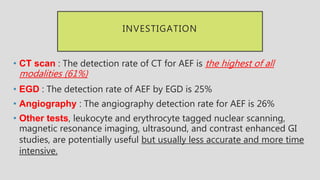

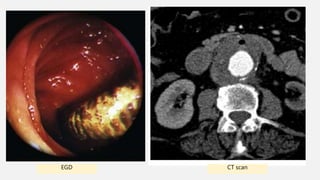

3. Clinical presentation of AEF includes gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal pain, and a pulsatile abdominal mass. Diagnosis is made using CT scan, endoscopy or angiography.

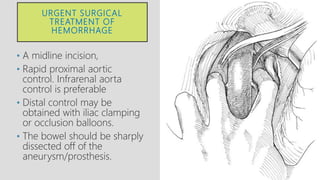

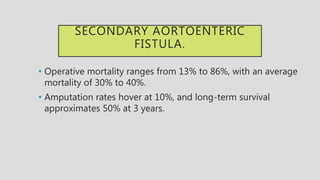

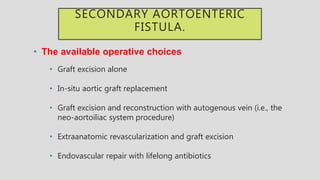

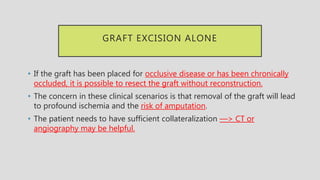

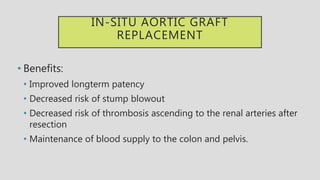

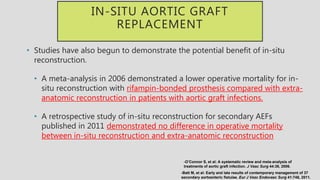

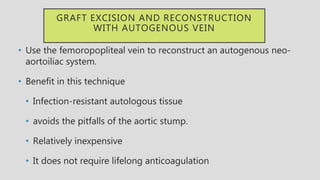

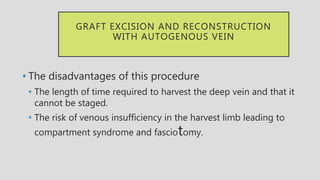

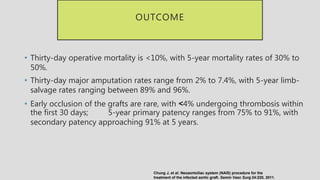

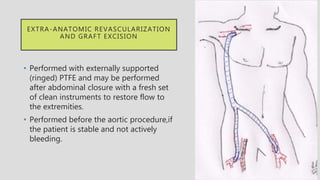

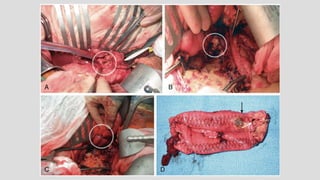

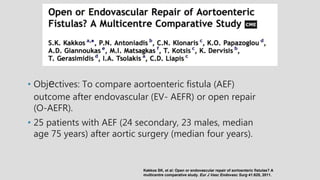

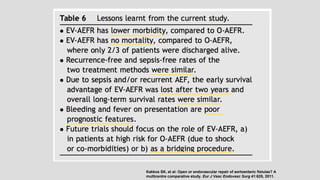

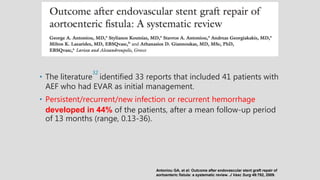

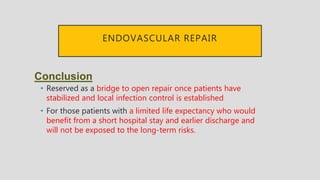

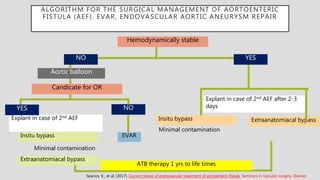

4. Treatment requires urgent surgery to control hemorrhage and resection of infected material. Reconstruction options depend on the extent of infection