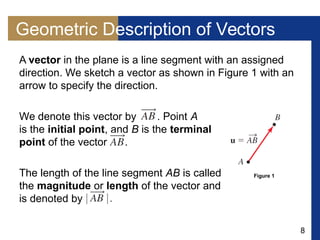

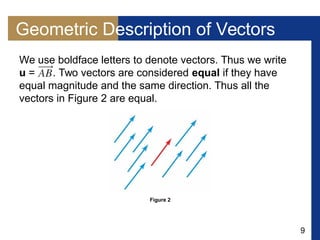

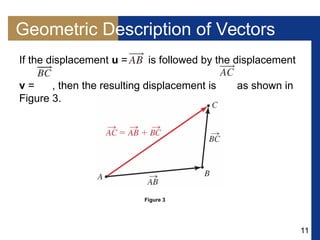

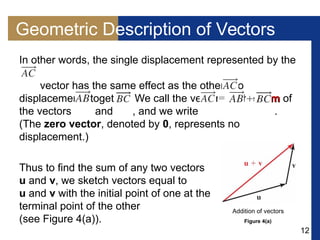

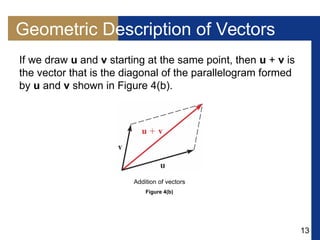

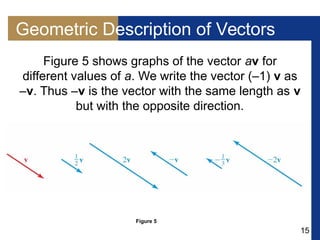

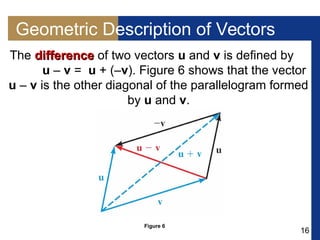

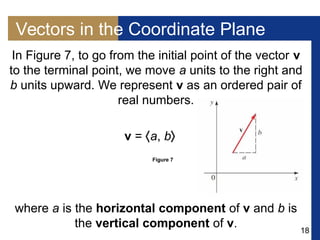

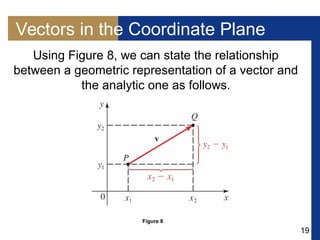

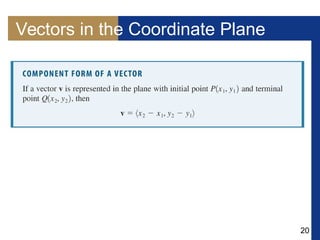

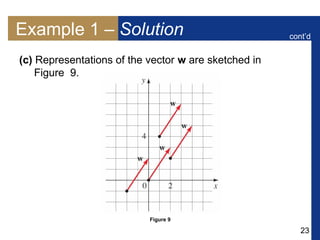

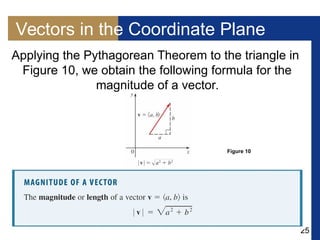

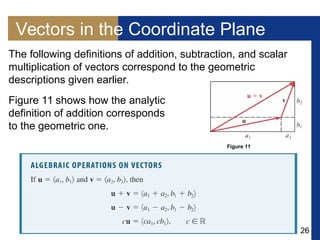

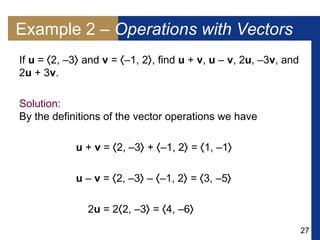

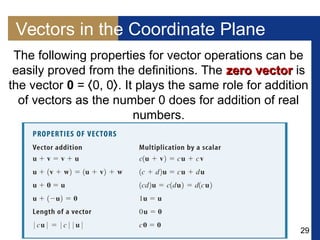

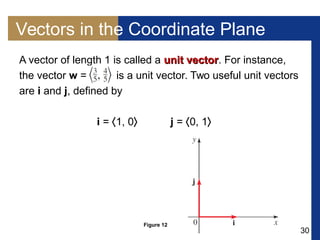

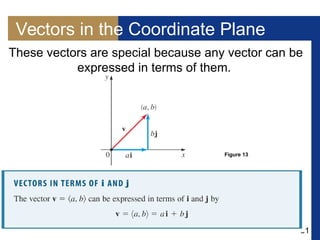

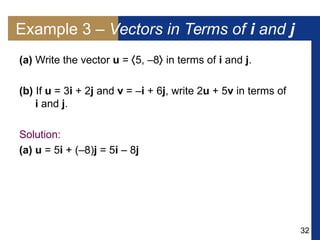

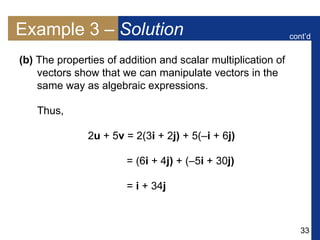

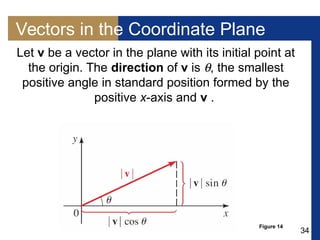

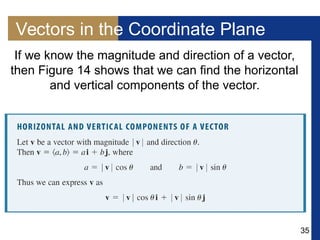

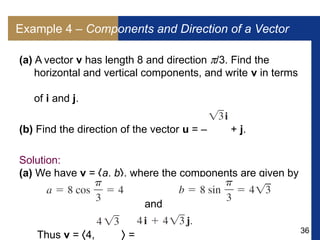

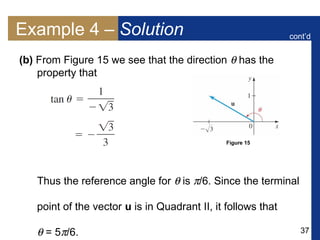

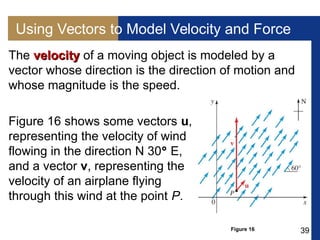

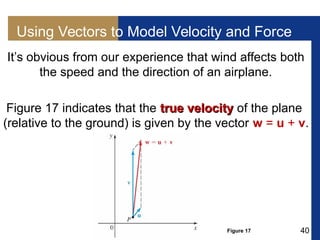

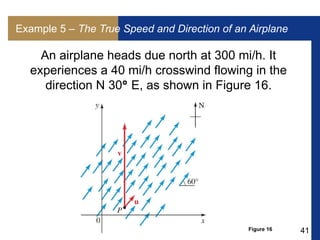

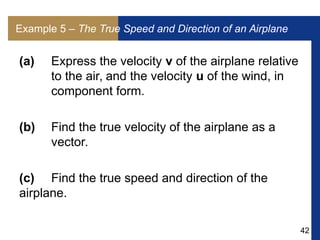

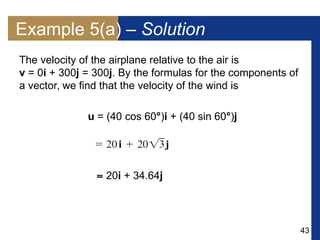

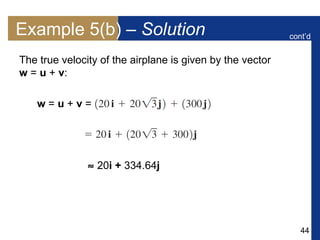

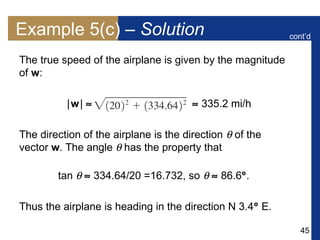

The document discusses vectors and trigonometry. It begins by defining vectors as quantities with both magnitude and direction, such as displacement and velocity. It then covers geometric descriptions of vectors using arrows to represent direction. It also discusses vector operations like addition and scalar multiplication analytically and geometrically. Finally, it shows how vectors can model velocity and how to calculate the true velocity of an object when it experiences additional velocities like wind.