This document provides an overview of piping and instrumentation diagram (P&ID) development. It discusses the importance of P&IDs and the development process. Key parties involved in P&ID development include engineering, operations, and maintenance. The document also outlines the anatomy of a P&ID sheet and general rules for drawing P&IDs, including showing items, identifiers, and different types of diagrams. Principles of P&ID development include addressing normal and nonroutine operations as well as provisions for maintenance and future changes.

![Piping and Instrumentation Diagram Development

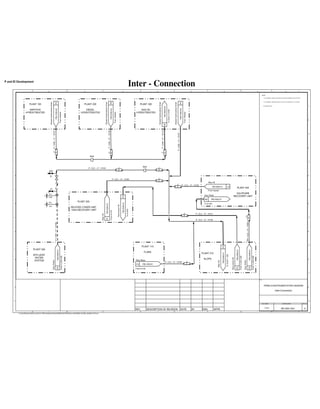

16

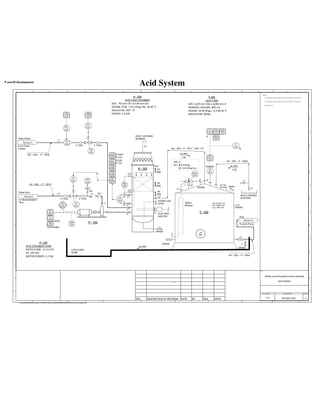

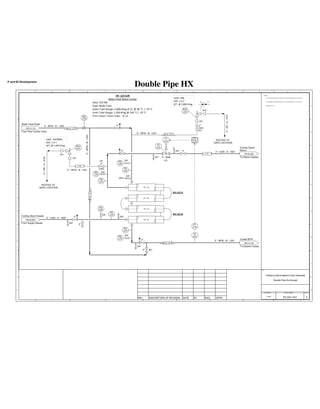

The Revision block basically shows the creation history

of a PID sheet. By studying the Revision block, one can

know when each revision of PID was issued and who

are involved in the PID development and approval. The

different revisions were discussed in Chapter 2.

3.5 Comments Block

The Comments block is the area where everything that

cannot be pictured in the main body of a PID is shown.

It can have a Holds area and a Notes area (Figure 3.6).

The Holds area is not used by all companies. The

general rule in PID development is that if an item or a

portion of a PID does not meet the quality and com-

pleteness expected for a given revision level, it should be

clouded and the word hold should be written near the

border of the cloud.

Completeness in regard to the revision level of a PID

is very important. If whatever is incomplete is supposed

to be clouded, all the items on the first revision of a PID

(e.g. issue for review [IFR]) should be clouded. But this is

not always the case. In an IFR revision of a PID sheet,

only the items that should be clouded are those that are

expected to be completed and firm in the IFR revision

but are not. Therefore, to be able to decide if one item on

the PID should be clouded, company guidelines should

be followed. In the case of lack of company’s guideline,

Table 19.4 in Chapter 19 can be consulted.

Notes:

Holds:

Reference drawings Revision

block

Company’s logo

Engineering seal

Company registration

Title block

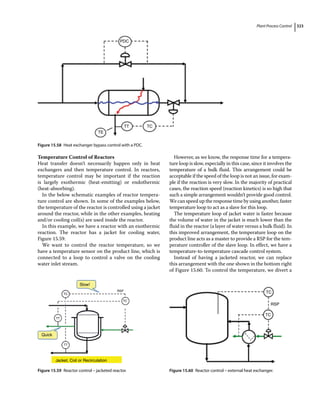

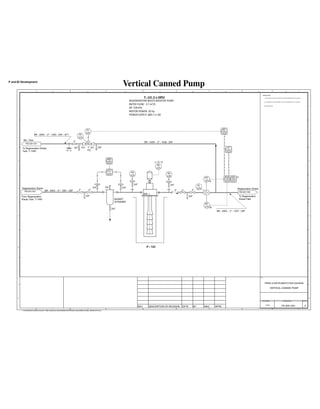

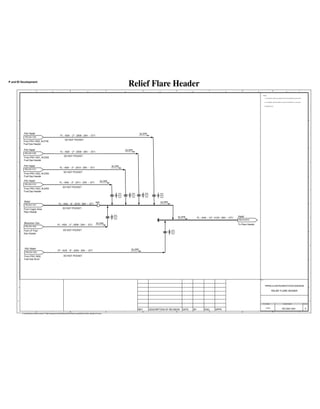

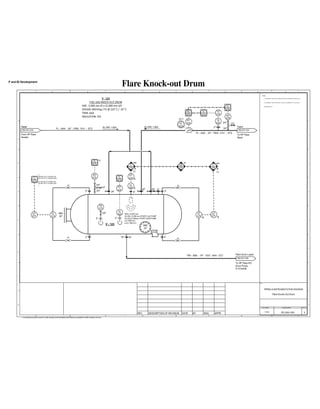

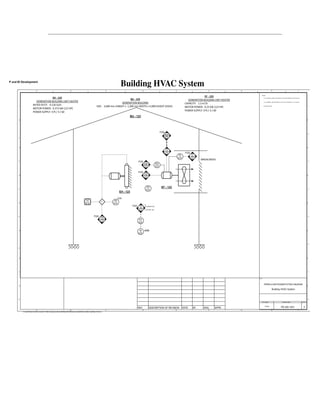

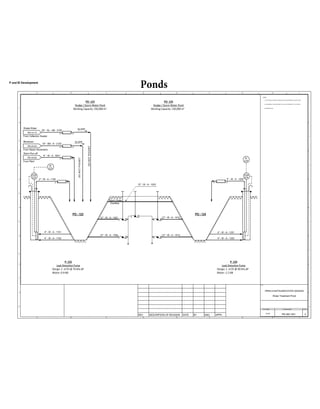

Figure 3.1 The outline of a PID sheet.

Figure 3.2 Typical Title block.

Engineer and permit stamps

This document was prepared exclusively

for XXXX by YYYY and subjects to the

terms and conditions of its contract with

YYYY.......

Legal terms

Permit to practice

Signature:----------

Date:-----------------

Permit number:-------

Figure 3.3 Typical Ownership block.

DWG.No. Reference drawings REV.

A

HVAC detail DWG.

52-27-002

Figure 3.4 Typical Reference block.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pipingandinstrumentationdiagramdevelopment-230302184324-9a1d2221/85/Piping-and-Instrumentation-Diagram-Development-pdf-36-320.jpg)

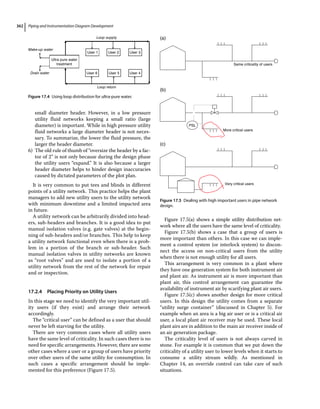

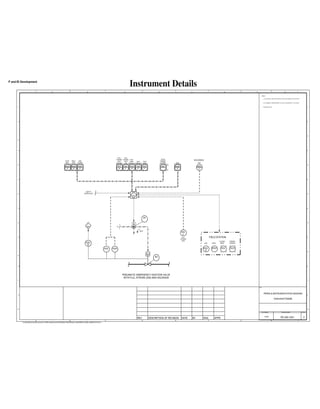

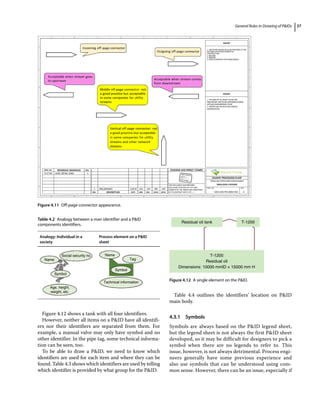

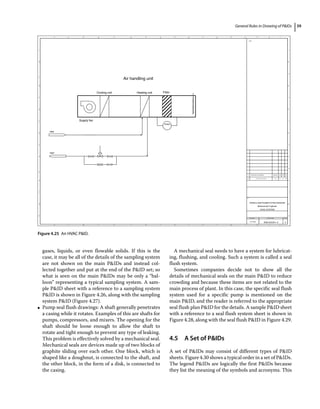

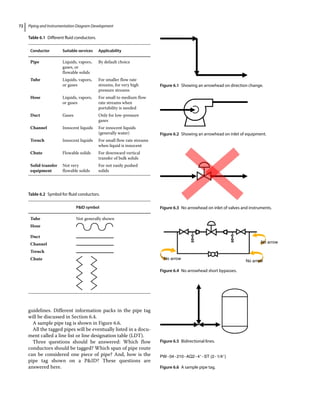

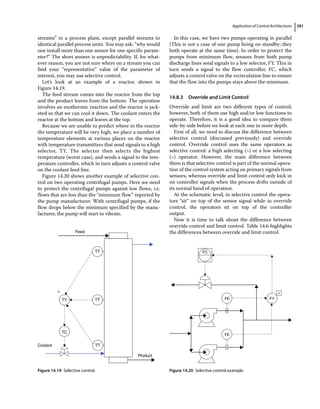

![General Rules in Drawing of PIDs 31

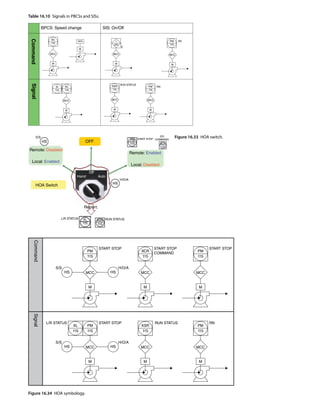

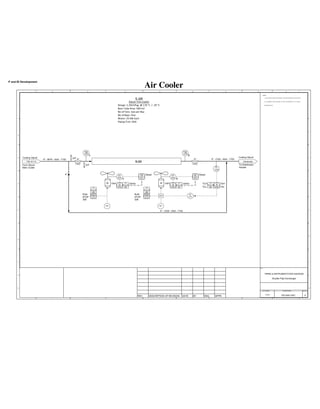

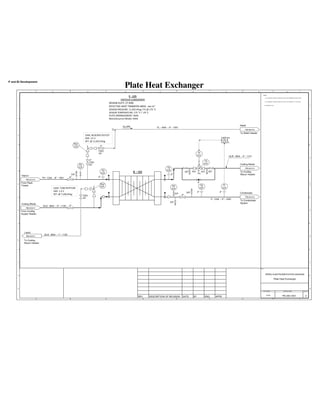

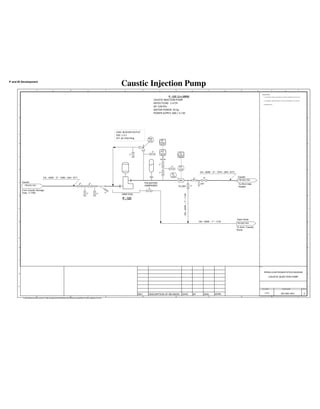

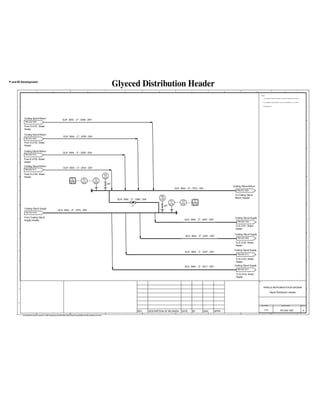

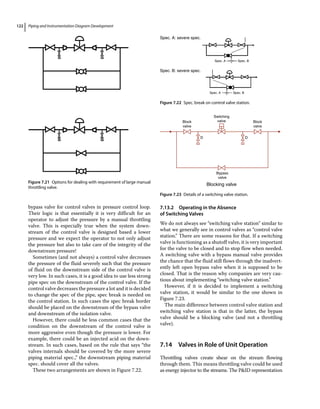

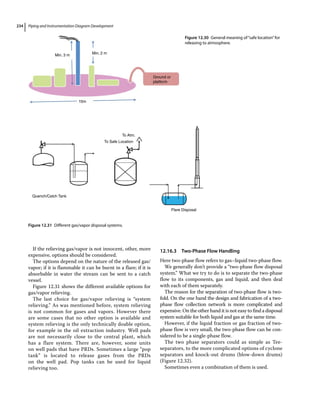

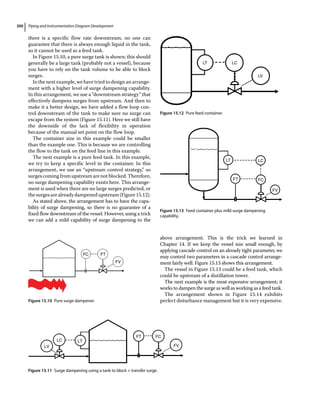

So, the sparing philosophy for tires for the car in this

example is 5×25%; this means four of them are operating

tires and one of them is a spare.

How is 5 × 25% interpreted as four operating ties and

one spare tire?

100

25

4 4 operating tires

5 4 1 1 spare tire

The 100 in the calculation is a fixed number.

In process plants, the sparing philosophy is a parame-

ter that is mainly defined as a need for parallel units. For

single equipment, the sparing philosophy is simply

1×100% and possibly does not need to be mentioned on

the PIDs. The other examples of sparing philosophy is

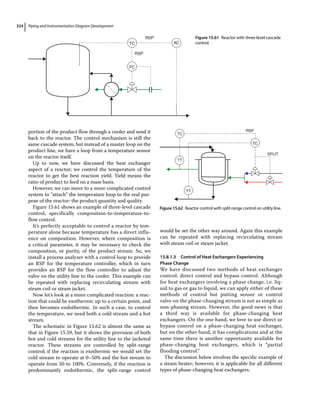

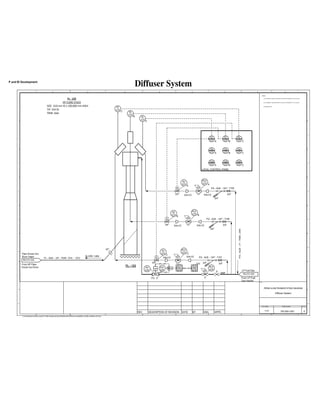

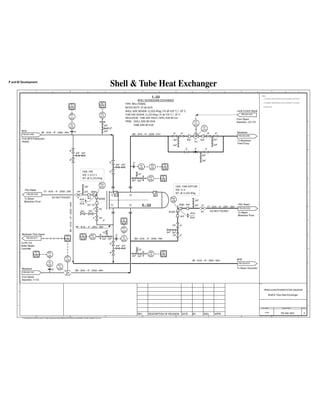

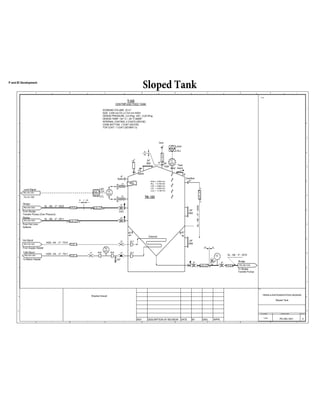

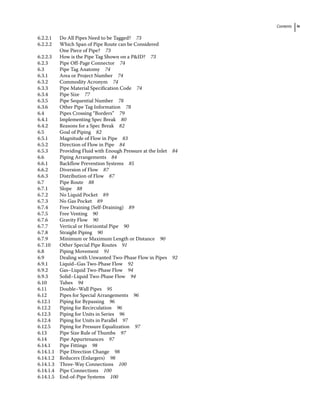

shown in Table 4.6.

There are some variations of expressing a sparing

philosophy. For example, there can be three sand filters

in parallel that all function during normal operation, but

when one of them is out of service and backwashing is

applied, just two of them are doing the filtration. This

sparing philosophy can be shown in Figure 4.16.

However, when the sparing approach is more compli-

cated, it could be more difficult to show it as a simple

block of a number of parallel equipment multiplied into

a percentage value. More complicated type of sparing

schemes will be discussed in Chapter 5.

Design pressure and design temperature are the next

items in an equipment callout. The design pressure is the

pressure with which the container or a piece of equip-

ment can operate continuously with no safety hazard.

Equipment tag Equipment name

Main equipment parameter(s) [one or two]

Sparing philosophy

Trim no.

Lining/coating/insulation

DP@DT

Figure 4.15 The anatomy of a callout.

Water from source

Dirty B/W water

Dirty B/W header

Treated water header

To waste management system

From wells

From treated water tank

FC

11

SG

12

SG

11

KV

11 21

FY

11

FC

21

SG

22

SG

21

KV

FY

21

FT

11

FE

11

FT

21

FE

21

31

FC

31

SG

32

SG

FL-100A FL-100A FL-100B

31

KV

FY

31

FT

31

FE

31

Filtered water

To treated water tank

Clean B/W water

Feed water header

200-FL-100 A/B

Water sand filter

Capacity: 600 m3/h

Sparing philosophy:

3×33% (normal)

2×50% (backwash)

B/W header

Figure 4.16 Sparing philosophy of three filters during normal operation and only two filtering during backwash.

Table 4.6 Examples of sparing philosophies.

Sparing philosophy notation Sparing philosophy meaning

1×100% 100

100

1 1Operating

1 1 0 No Spare

2×100% 100

100

1 1Operating

2 1 1 1 Spare

3×50% 100

50

2 2 Operating

3 2 1 1 Spare

4×33% 100

33

3 4 Operating

4 3 1 1 Spare

5×25% 100

25

4 4 Operating

5 4 1 1 Spare](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pipingandinstrumentationdiagramdevelopment-230302184324-9a1d2221/85/Piping-and-Instrumentation-Diagram-Development-pdf-50-320.jpg)

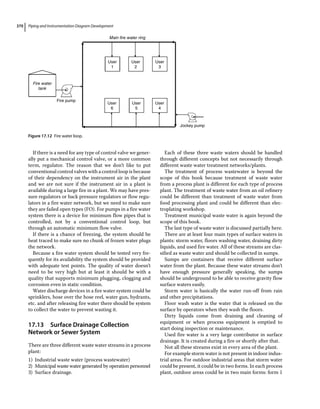

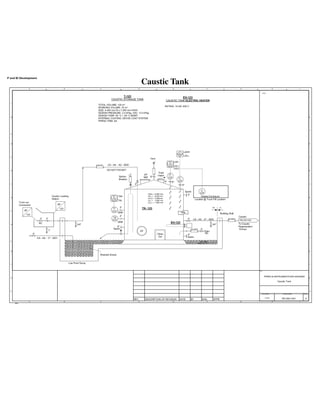

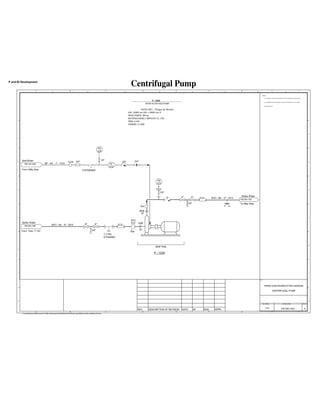

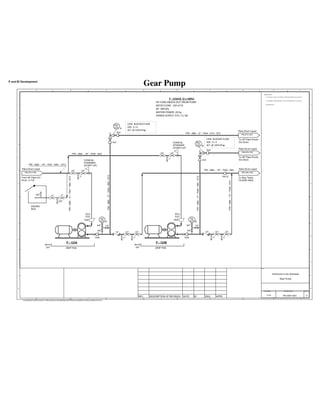

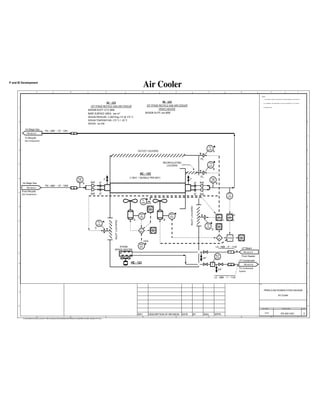

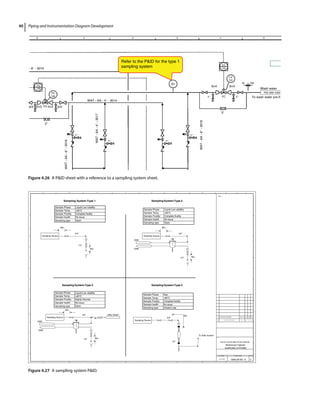

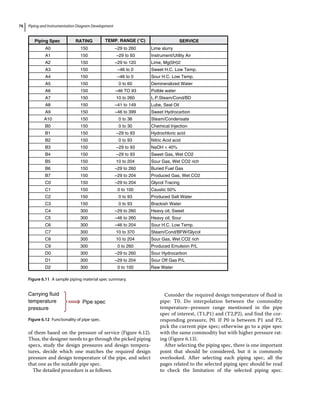

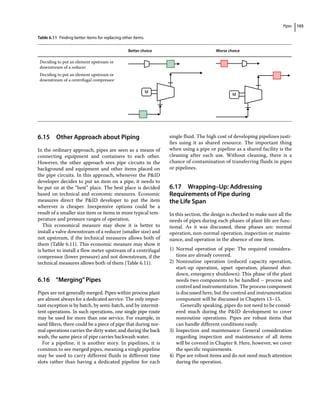

![Principles of PID Development 55

the flow rates that fail to fill the cylinder of the pump in

one stroke. Partial filling of the cylinder may cause some

damage to mechanical components of the pump in the

long term. This minimum flow is a function of cylinder

volume and stroke speed of a specific pump.

The TDR of a pipe is a bit more complicated. Here the

minimum flow should be defined as the minimum flow

that does not fall into laminar flow, or the minimum flow

that keeps a check valve open. For liquid flows in pipes,

the minimum flow can be interpreted as the minimum

flow that makes the pipe seal (no partial flow pipe)

because a flow smaller than that will freeze in an outdoor

pipe. If the flow contains suspended solids, the minimum

flow should prevent the sedimentation of suspended

solids.

Table 5.5 is a table of typical TDR of some equipment.

Table 5.6 shows the large TDR of storage containers.

The high TDR of these items also explains why contain-

ers are used for surge dampening in plant‐wide control

practices.

In some cases, deciding on the required TDR needs

additional consideration. One example is a chemical

injection package. TDR is important for chemical injec-

tion packages to ensure that there is no time that chemi-

cal overdoses or underdoses happen, if both of them are

intolerable to the process.

It is popular to expect to see a chemical injection pack-

age provide a TDR of about 100:1 or lower; possibly 10:1

can be provided by stroke adjustment and another 10:1

through VFD. But why is such large TDR is necessary if

the host flow experiences only 2:1? This huge TDR is

generally because of the uncertainty in required chemi-

cal dosage and abundance of chemical producers. If the

dosage is fairly firm and the chemical is a nonproprietary

type, the TDR can be decreased to lower the cost of the

chemical injection system.

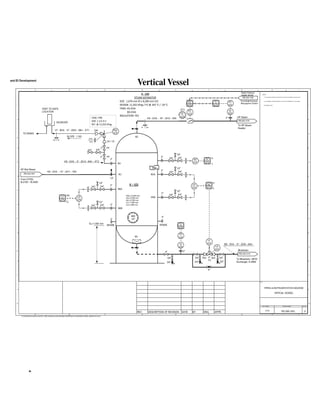

5.4.2.1.2 Flexibility of Utility Networks

The flexibility of utility networks is also defined by TDR.

As mentioned, when a TDR of, for example, 2/1 in a plant

is requested, the TDR of utility network should be higher.

As the utility system needs a large TDR, it generally

needs a container in the utility production area to absorb

the fluctuations caused by the utility usage change in

process areas. Table 5.6 shows the name of these surge

containers in different utility systems.

The utility network by itself experiences different levels

of turndown, and consequently it needs different TDR. The

main header can need the minimum TDR, whereas the

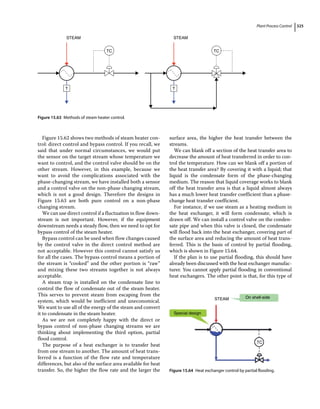

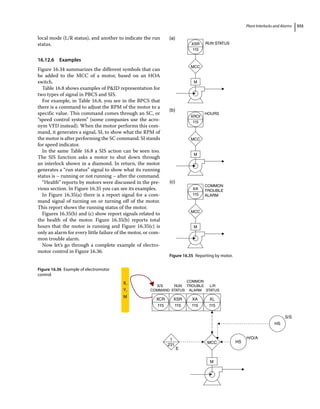

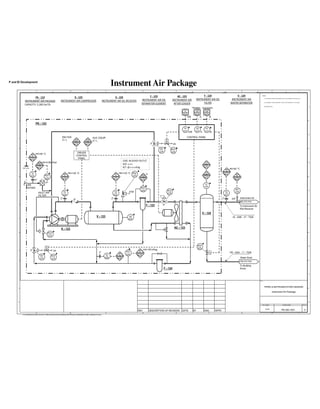

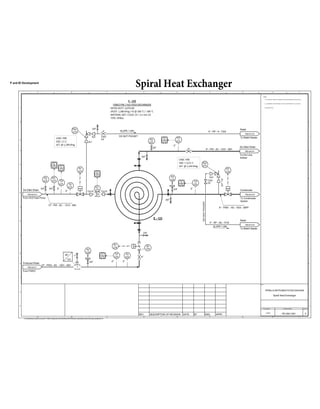

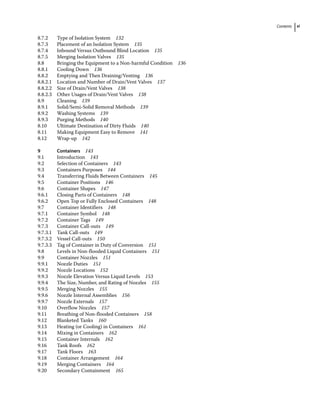

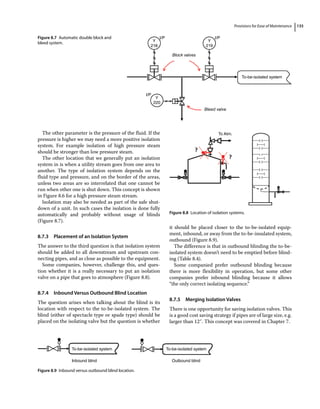

subheads may need a higher or lower ratio (Figure 5.18).

Achieving a high TDR for the utility network and

instruments is not difficult. The utility network is mainly

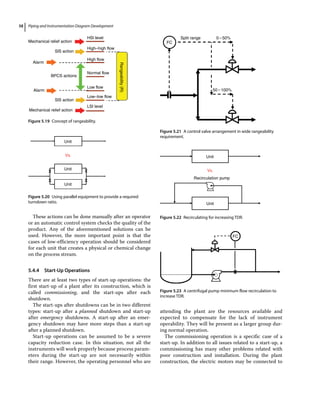

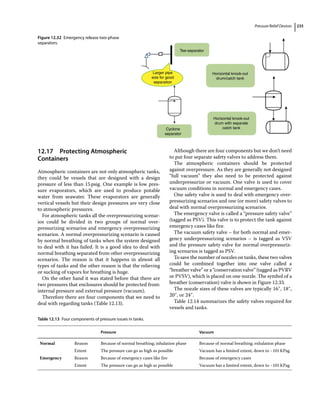

Mechanical relief action

Mechanical relief action

SlS action

SlS action

Alarm

Alarm

BPCS actions

High–high flow

HSl level

High flow

Normal flow

Low flow

Turn-

down

ratio

(TDR)

Low–low flow

LSI level

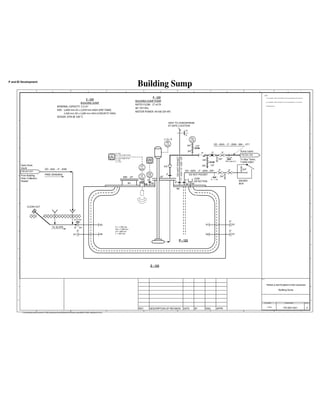

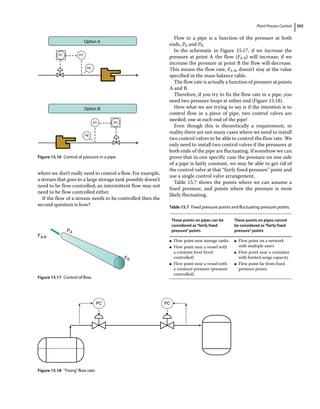

Figure 5.17 Concept of turndown ratio.

Table 5.5 Turndown ratio of some selected equipment.

Item Turndown ratio

Pipe Large but depends on the definition of

maximum and minimum flow.

Storage

containers

(tanks or

vessels)

Very large (maximum is total volume of the

container, but minimum could be dictated by

downstream item. For example a centrifugal

pump dictates a minimum volume to provide

required net positive suction head [NPSH]).

Centrifugal

pump

Typically 3:1–5:1

PD pump Theoretically Infinite

Heat

exchanger

Small, depends on the type (e.g. less than

1.5:1)

Burner Depends on the type between 2:1 to 8:1

Table 5.6 Utility surge container to provide turndown ratio.

Utility Surge container

Instrument air (IA) Air receiver

Utility water (UW) Water tank

Utility steam (US) Steam drum in conventional

boilers (in steam generators

cannot be stored; the system

design should be in a way to

“float” US with other streams.

Utility air (UA) No dedicated container can

“float” with IA

Cooling water (CW) Cooling tower basin

Cooling or heating

glycol

Expansion drum](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pipingandinstrumentationdiagramdevelopment-230302184324-9a1d2221/85/Piping-and-Instrumentation-Diagram-Development-pdf-74-320.jpg)

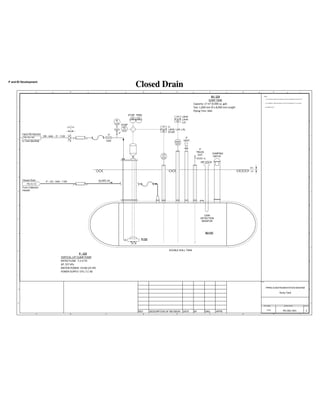

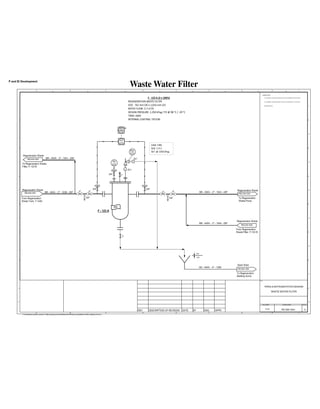

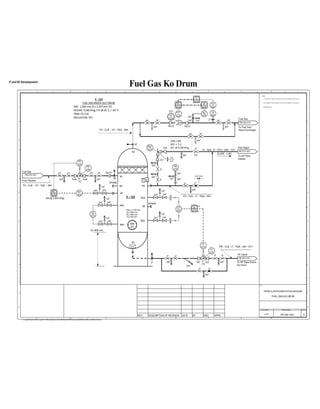

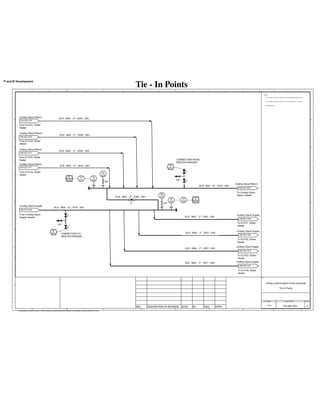

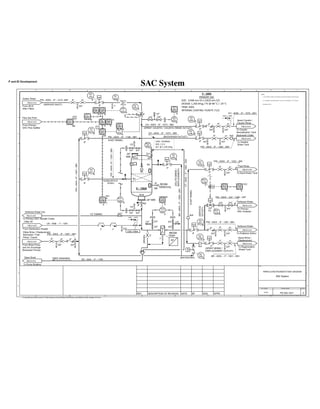

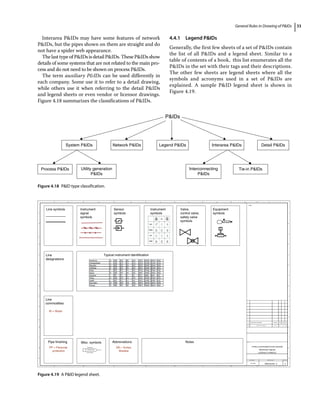

![Principles of PID Development 61

make the equipment needier for maintenance. These

two components are discussed next.

The equipment that are static generally need less

maintenance. Among nonstatic equipment (i.e. dynamic

equipment), the ones with linear (reciprocating) move-

ments may need more maintenance attention than the

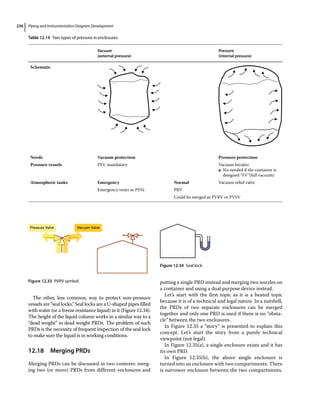

ones with rotary movements (Figure 5.25).

Where there is a rotating shaft in a piece of equipment,

the high rotational speed shafts (high revolutions per

minute [RPMs]) may need more maintenance attention

than low RPM shafts. Pieces of equipment that have tight

clearances may need more inspection and maintenance.

This is especially true if they are being used in services

that are not clean.

When it comes to process and process conditions, the

equipment that works in very high or very low tempera-

tures or pressures may need more maintenance atten-

tion. The equipment that processes non‐innocent fluids

(i.e. highly acidic, precipitating, scaling, fouling, or any

other aggressive fluid) may need more maintenance

attention.

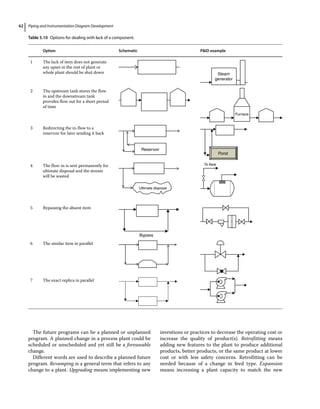

5.4.7 Operability in Absence of One Item

The designer needs to decide the repercussions of equip-

ment loss, which means in the absence of a piece of

equipment, it needs to be decided what will happen to

the rest of unit or plant. The wide range of answers and

decisions include:

1) Do nothing! In this case, the piece of equipment,

unit, or even plant should shut down in the absence of

a piece of equipment or instrument. This option

should be avoided. Sometimes it is inevitable when a

piece of equipment of interest is the main or one of

the main pieces of equipment of the plant.

2) Accumulation of fluid in middle containers. In this

solution, placing two containers with enough resi-

dence times upstream and downstream of the absent

component help to prevent the absence of the compo-

nent get “visible” by the rest of plant. In this solution,

the upstream container allows the accumulation of

fluid, and the downstream container provides flow for

the downstream units.

3) Redirecting the in‐flow to a “reservoir” for later

usage. In this solution, the feed to the equipment can

be redirected to a temporary reservoir (like waste

tank or pond) to be processed later by returning it

back to the system. Usually this is solution is not avail-

able for gases or vapors.

4) Redirecting the in‐flow to an “ultimate disposal”

system. This solution is the same as previous one, but

the flow sent to the external reservoir cannot be

returned. The feed to the equipment can redirected

to a waste‐receiving system, like a flare system. This

option can be considered if the preceding option is

not doable. The previous option is definitely a better

option because valuable materials are not lost.

5) Bypassing the absent item. The feed to the equip-

ment can be bypassed temporarily with marginal

impact on the operation of the system, like bypass-

ing a trim heater if being off‐temperature does not

hurt the plant for a short time. There are some cases

that is decided to bypass the equipment or unit when

it is out of operation. This can be done if the lack of

equipment or unit does not affect the process in the

short term.

6) The nearly “similar” item in parallel. A nearly simi-

lar system in parallel can take care of the flow that

used to go to the absent system but not necessarily

with the same quality. One example is having a man-

ual throttling valve (e.g. globe valve) in a bypass loop

of a control valve. The other example is placing a

bypass pipe for a pressure safety valve (PSV) together

with a pressure gauge (or pressure gauge point) and a

globe valve. In the case of pulling the PSV out of oper-

ation, an operator will act as a PSV by monitoring the

pressure of the container and being prepared to open

the valve if it is needed.

7) The exact “similar” item in parallel. A parallel,

exact replica as spare system can take care of the flow

that used to go to the absent system. This is the most

expensive option. The examples are all spare pumps

or spare heat exchangers (in very fouling services).

Spare equipment are very common for fluid‐moving

equipment as usually the pumps and compressors

cannot be handled otherwise. One important exam-

ple is having two fire pumps in parallel with two dif-

ferent types of drives (i.e. one electromotor and the

other one a diesel drive pump). The spare can be in

different forms.

In Table 5.10, the schematics of these options in the

PID are shown.

5.4.8 Provision for the Future

The other concept that may affect the development of

the PIDs are provisions for the future. The future

arrangement of a plant is not necessarily similar to the

current arrangement of plant because the future of a

market is not always foreseeable, or if it is foreseeable, it

is not economically justifiable to incorporate it into the

current plant design. However, to minimize the cost of

rearrangement of a plant in the future, some items can be

placed in the plant design and the PID. Therefore,

some “footprints” of future on a PID may be seen; how-

ever, not all plants consider the future.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pipingandinstrumentationdiagramdevelopment-230302184324-9a1d2221/85/Piping-and-Instrumentation-Diagram-Development-pdf-80-320.jpg)

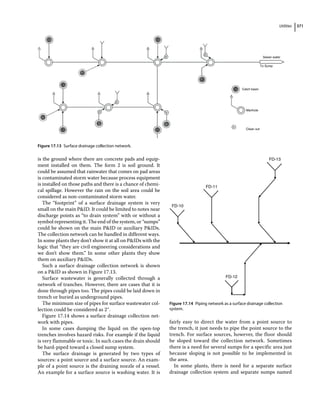

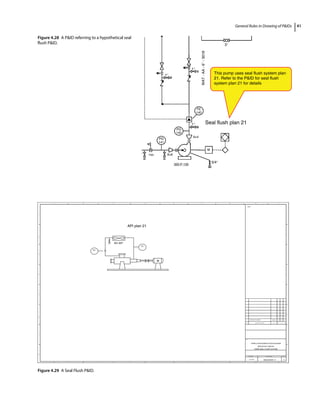

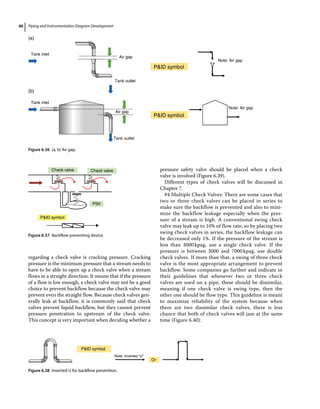

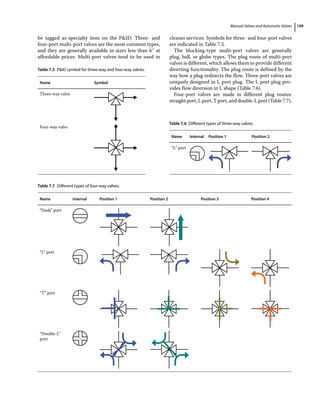

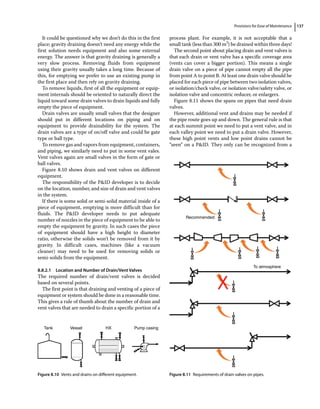

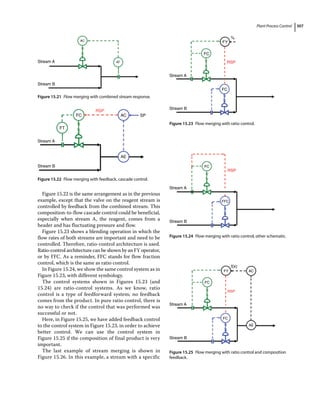

![Pipes 85

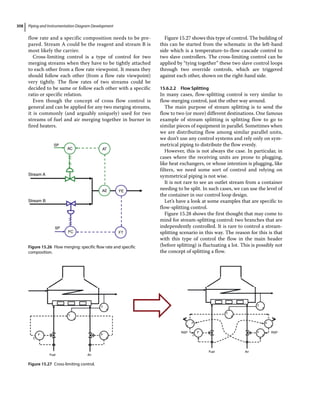

In this arrangement, the first thing to be considered is

making sure that the flow goes in the direction intended.

For all the cases of a single‐source, multiple‐destination

pipe, multiple‐source, single‐destination pipe, and multiple‐

source, multiple‐destination pipe having multiple points

as source or destination is common. For simplicity, only the

cases that have multiple destinations will be discussed.

For these cases (as seen in Figure 6.35), the process

requirement could be one of these goals: diverting or

distributing the flow.

In diverting the flow, the goal is to transfer the flow to

only one user at a time, while in distributing the flow, the

goal is to direct the flow with different magnitudes to

multiple users at the same time.

It means that in a multipoint source or destination in

addition to making sure the flow is in the right direction,

secondary goals should also be achieved.

The following sections explain how to satisfy the

requirement of different pipe arrangements.

6.6.1 Backflow Prevention Systems [1]

When faced with the issue of reverse flow in pipes, the

process design engineer usually uses a check valve to

prevent the reverse flow. However, using a check valve is

not the best method to prevent reverse flow. There are at

least four different techniques to prevent backflow,

which will be discussed based on their level of effective-

ness in preventing reverse flow.

#1 Air Gap: An air gap is the best way to prevent back-

flow. When an air gap is placed in a flow route there is

absolutely no backflow in the system. However, this

method has some disadvantages. The first is that an air

gap is only applicable for liquid streams; they do not

work on gas streams. The second is that there could be

contamination of the liquid because the stream is

exposed to the environment. Therefore, the environ-

ment should be clean, or the cost of cleaning up the con-

tamination should be factored in. The other downside of

an air gap is that if the weather is cold, there is a chance

of freezing and system failure. However, if somehow all

the disadvantages of an air gap are resolved, it provides

one of the best backflow prevention techniques. An air

gap could be placed in a pipe route or in a tank, and both

are shown in Figure 6.36. It is common to see an air gap

in potable water piping where there is a chance of back-

flow and contamination of portable water with other

contaminated waters.

#5 Backflow‐Preventing Device: Backflow‐preventing

device is a type of device that can be used in clean ser-

vices and is common in water streams. In the casing of a

backflow preventing device, there are two check valves in

series and one pressure safety valve between two check

valves in one casing. If a backflow‐preventing device is

used in a PID, it should be tagged as a specialty item

(SP item) (Figure 6.37).

#2 Inverted U: An inverted U is another way to prevent

reverse flow in a pipe. This method also works only on

liquid streams. By creating a specific arrangement in a

pipe, the backflow of a liquid stream can be prevented.

This arrangement is a vertical upside down U. The height

of this inverted U depends on the pressure of liquid flow

when reversing back. Because of that, in some cases in

which reverse flow pressure is high, the height of the

upside down U will be beyond a practical value. In such

cases, an inverted U cannot be used (Figure 6.38).

#3 Check Valve: Check valves are the most common

way of preventing backflow. By placing a single check

valve and reverse flow, either a liquid stream or gas

stream will be prevented. However, a check valve always

leaks when trying to prevent backflow. Generally it is

assumed that the conventional swing check valve leaks

about 10% of the flow. The other important parameter

A0

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

B0

B1

B0

B0

B0

B1

B2

B2

A0

A0

A1

A1

A2

A2

A0

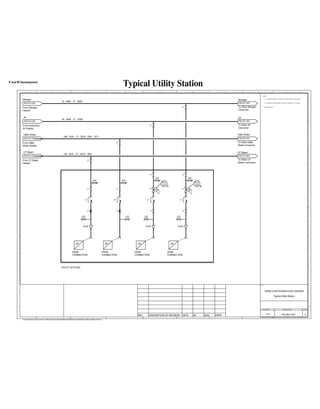

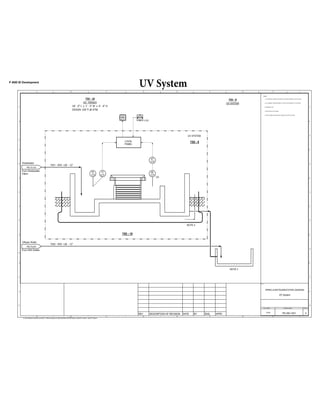

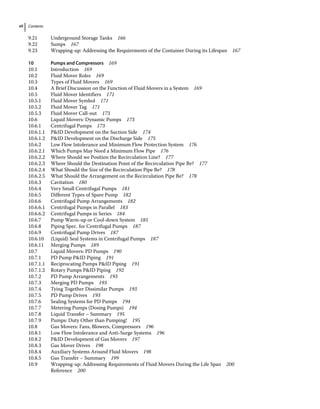

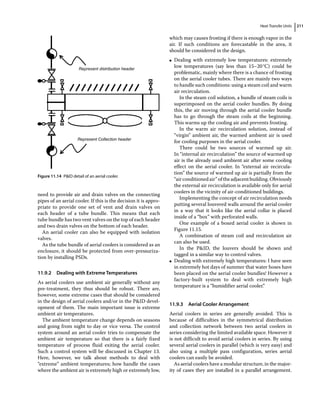

Figure 6.34 (a–d) Different piping arrangements.

A B

C

D

Figure 6.35 Multiple‐destination pipe arrangement.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pipingandinstrumentationdiagramdevelopment-230302184324-9a1d2221/85/Piping-and-Instrumentation-Diagram-Development-pdf-104-320.jpg)

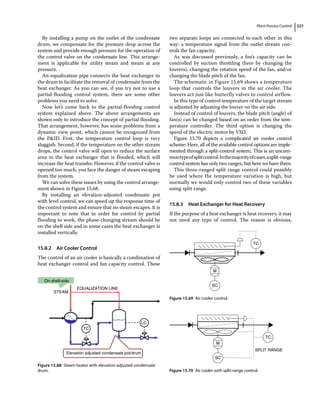

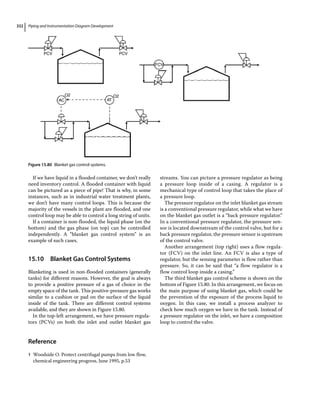

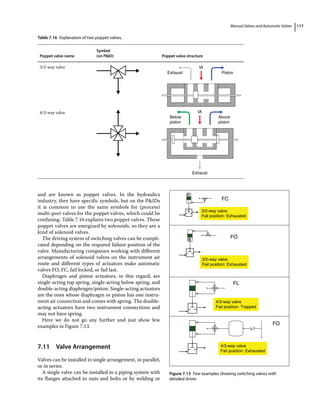

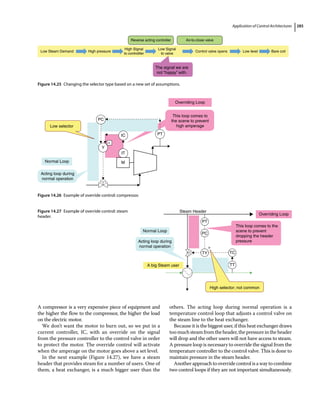

![Piping and Instrumentation Diagram Development

116

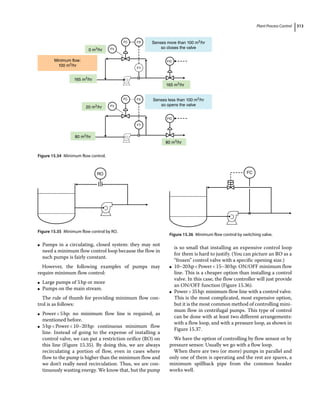

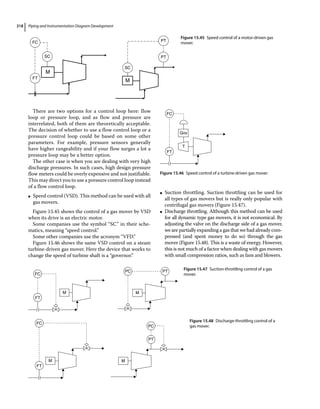

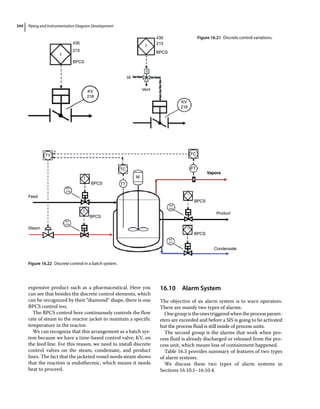

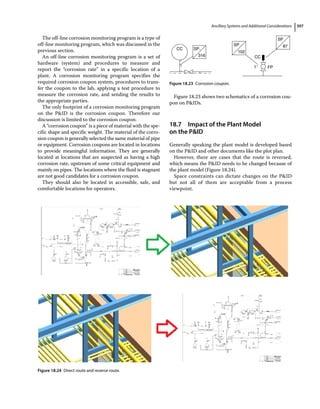

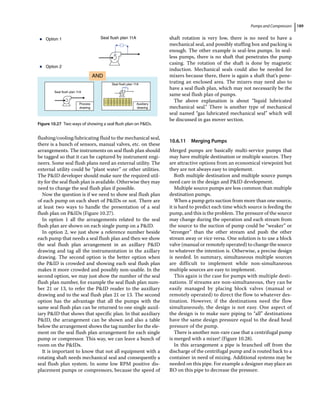

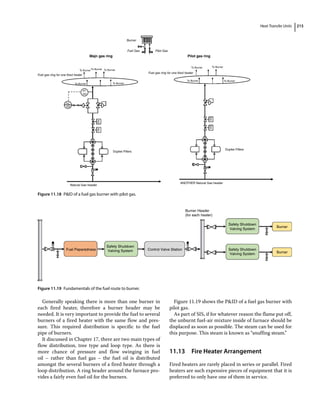

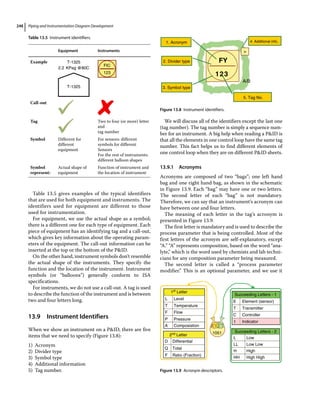

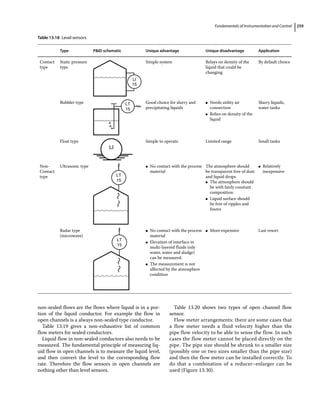

Table 7.15 Automatic valves on PIDs.

Simplistic presentation Detailed presentation

Control valve

FV

FV

P/I

FY

Switching valve

KV

KV

S

Vent

IA

In some types of actuators (i.e. diaphragm and piston

actuators), there are two energy streams as the actuator

driver: instrument air and DC electricity. In these actua

tors, instrument air moves the main actuator element to

push the valve’s stem. But the instrument air is initiated

to the actuator through one solenoid valve or an arrange

ment of solenoid valves, which are functioning via DC

electricity. If either of these gets lost, the actuator fails to

function.

Losing instrument air is known as a power loss and

losing DC electricity is known as a signal loss [1].

To what type of failure does the failure position of an

automatic valve refer? Losing instrument air or losing

DC electricity?

If failure position of an automatic valve is mentioned

without any specifics, it is generally because of power

loss. However, to prevent any confusion, it is better to

clearly mention if the failure position is for power loss or

signal loss.

The letter P at the beginning of acronym for failure

position shows it is for power loss, and an S represents

signal loss (Table 7.14).

A process engineer generally wants to have an auto

matic valve with the same failure position for power

loss and signal loss. Complications can arise if a design

process engineer asks for a failure positions in signal

loss differently than in power loss. The automatic valves

generally report the failure position in cases of power

loss unless another option is needed.

●

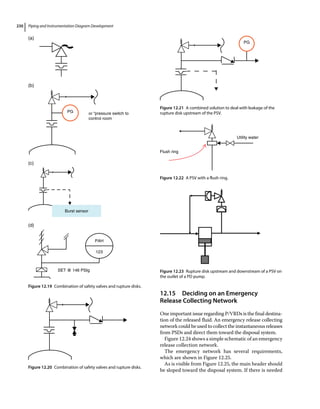

● Actuator Driving System

Showing the driving system of valve actuators on the

PIDs are different for each company. Some decide to

show all the details of the driving mechanism, and others

show only a brief schematic of the system and refer the

reader to other documents for details of the system.

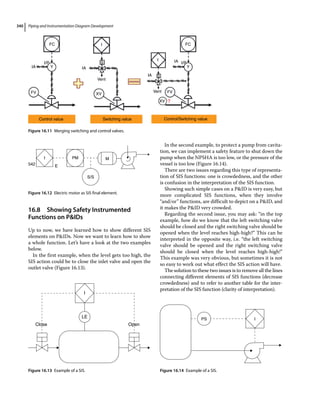

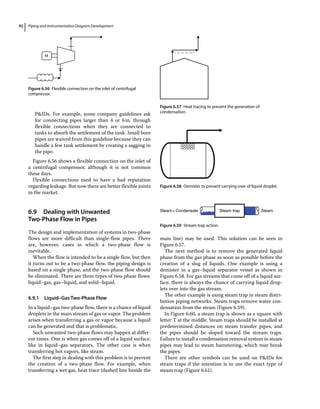

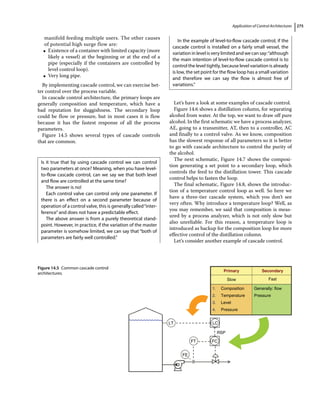

Table 7.15 shows different ways of displaying auto

matic valves on PIDs in regard to their driver system.

Chapter 13 discusses actuator driving systems in more

detail.

The symbol of a multi‐port valve in the detail of

drivers does not refer to process multi‐port valves.

These valves are common in the hydraulics industry

Table 7.14 Failure case acronyms regarding different types

of driver loss.

Driver loss type Name of drive loss Representing acronyms

Instrument air Power loss PFC, PFO, PFL, PFI

DC electricity Signal loss SFC, SFO, SFL, SFI](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pipingandinstrumentationdiagramdevelopment-230302184324-9a1d2221/85/Piping-and-Instrumentation-Diagram-Development-pdf-135-320.jpg)

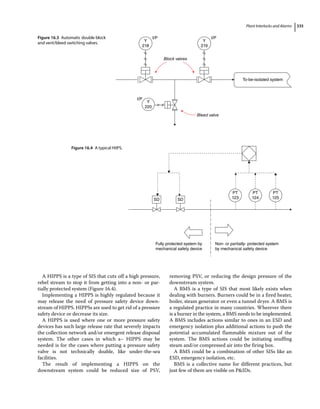

![Piping and Instrumentation Diagram Development

118

screwing its ports by fitting it between the flanges of the

two sides of pipes (Table 7.17).

Generally valves are installed between piping sides

without any other fittings. However, one important

exception is when installing control valves. Sometimes,

the selected control valve has smaller body size that can

be fitted with the pipe size. In such cases, a reducer on

the inlet of a control valve and one enlarger on the outlet

of the control valve may be needed.

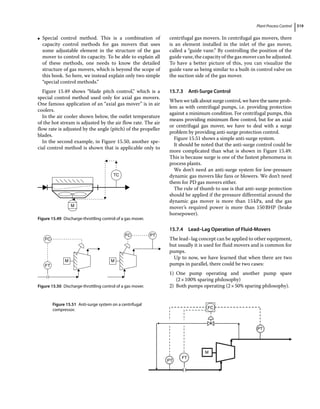

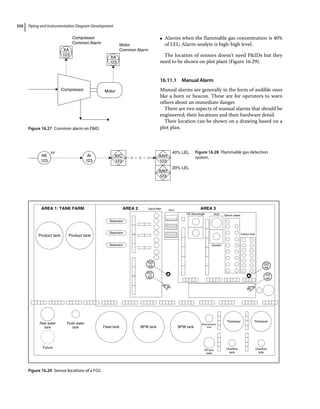

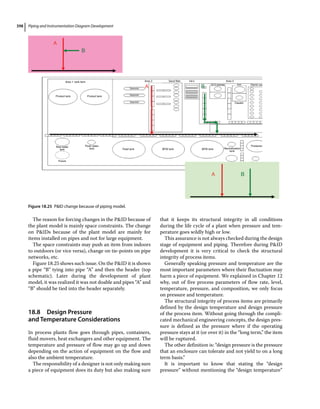

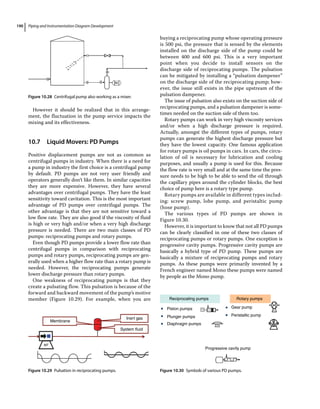

7.11.1 Valves in Series

A manual valve can be used in series, one blocking type

and one throttling type. If a stream needs to be adjusted

manually, and sometimes the stream should be totally

stopped and tight shutoff is important, it is a good idea

to use a manual blocking valve and then manual throt

tling valve in series (Figure 7.14). This arrangement can

be used in services like toxic fluids or high‐pressure

streams.

Two (or more) manual throttling valves or two (or

more) manual blocking valves are rare, which sometimes

is considered a bad practice in PID development.

However, sometimes having two or more manual block

ing valves in series happens. Each piece of equipment

needs isolation valves around it for ease of maintenance.

However, when there are two pieces of equipment, one

upstream and one downstream, and they are close to

each other, two of their isolation valves sit close to each

other in a series position. In such cases, one isolation

valve can be eliminated (Figure 7.15).

Valve arrangement in series can be used for control

valves or regulators. These are for the cases that a large

pressure drop is needed in a stream. A large dropping

pressure may cause vibration, noise, and erosion in the

valve [2].

A rule of thumb helps to decide when two regulators in

series may be needed:

●

● Where a pressure drop more than 100psig is needed

(or maximum 150psig).

●

● Where pressure should be dropped to a value less than

1/10th of upstream pressure.

●

● Where the pressure on downstream should be accu

rately regulated (e.g. less than few psig).

7.11.2 Valves in Parallel

The parallel arrangement of two manual valves may be

used. There are some cases that a manual blocking

valve needs to be placed on a stream that has high pres

sure. In such cases, placing one single blocking valve,

for example, a gate valve, makes life hard for the opera

tor who will have to open a manual valve from a fully

closed position under high pressure (e.g. more than

3000 KPa). To solve this problem, another smaller‐

sized manual blocking valve is installed in parallel with

the main valve. When the operator wants to open the

main valve, the small bypass valve is opened at the

beginning to equalize the pressure in both sides of the

main valve, and then the main valve can be easily

opened (Figure 7.16).

Parallel manual valves could be used for other reasons,

such as providing a minimum flow in the pipe even when

the main valve is closed or for start‐up. As was discussed

in Chapter 5, the general method of starting up a piece

of equipment involves gradually opening the valve of the

inlet stream. If the operator does not want to open the

valve suddenly, a parallel and smaller manual valve can

be added to the main valve and the operator can open it

Figure 7.16 Two manual blocking valves in parallel.

Table 7.17 PID symbol for connecting valves.

Valve size Connection type PID sketch

Nominal size 2″ Weld

Screw

Nominal size 2″ Flange

Eq1

Eq1

Eq2

If there are no branches

Eq2

Figure 7.15 Two manual blocking valves in series and saving

opportunity.

Blocking Throttling

Figure 7.14 Manual valves in series: blocking and throttling.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pipingandinstrumentationdiagramdevelopment-230302184324-9a1d2221/85/Piping-and-Instrumentation-Diagram-Development-pdf-137-320.jpg)

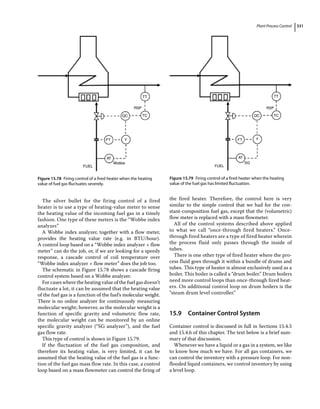

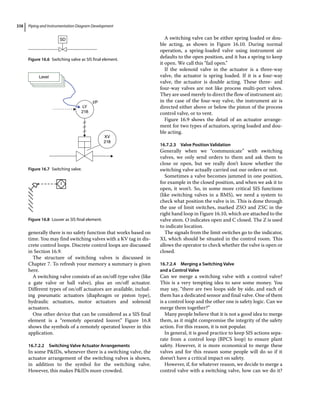

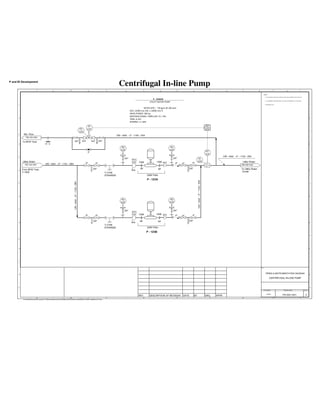

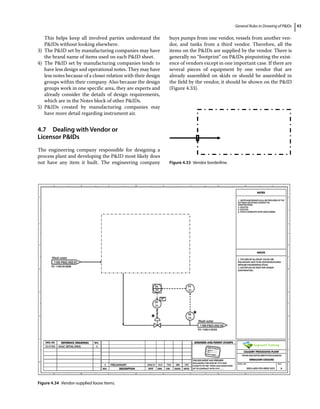

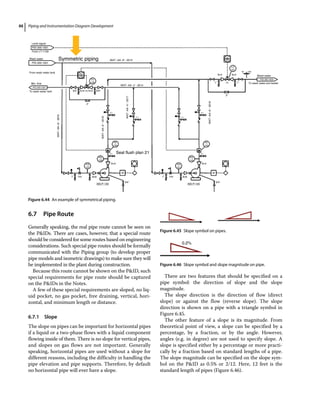

![Piping and Instrumentation Diagram Development

176

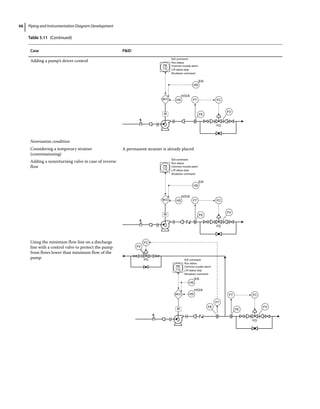

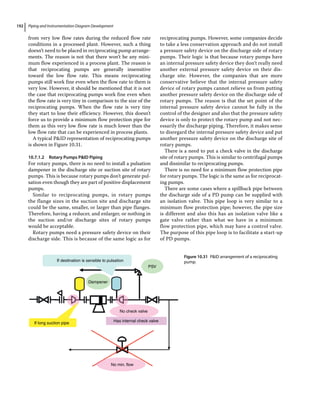

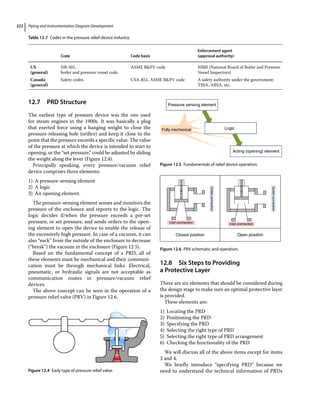

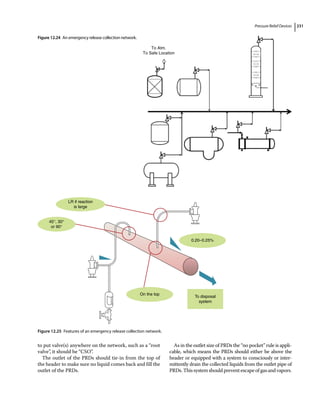

To explain the rest of the requirements for developing

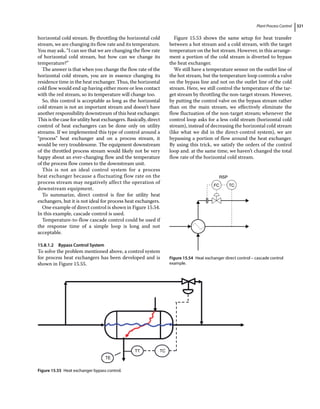

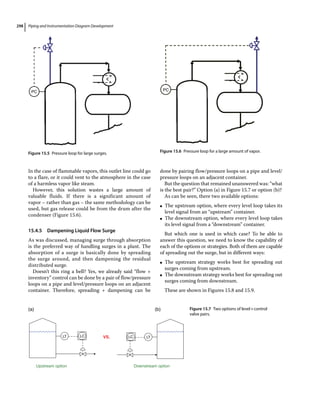

a PID for centrifugal pumps, two main weaknesses

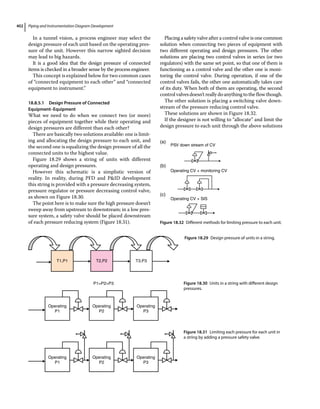

need to be discussed.

Centrifugal pumps have two main problems: cavitation

and low flow intolerance. When there is a weak point in

a piece of equipment, this should be addressed through

good process design and/or good control design.

When you are buying a centrifugal pump with a rated

capacity of 400 m3

h−1

, the seller tells you: “Thank you for

buying this and by the way, if you want to enjoy this new

pump, be careful about two things in particular (amongst

a bunch of other things!): first, this pump has a minimum

flow rate of (for example) 100 m3

h−1

, so please don’t feed

it with a lower flow rate than that.”

And second, be careful about the net positive suction

head (NPSH); this pump has a “required NPSH” of

(for example) 2 m, so please don’t feed it with a liquid

with less than 2 m of “available NPSH.”

In Section 10.6.2 these two weaknesses will be discussed

together with system process design and control design

methods to mitigate theses weaknesses.

10.6.2 Low Flow Intolerance and Minimum

Flow Protection System

“Minimum flow rate” is a flow rate that is reported by

the pump manufacturer, and if the pump receives a flow

rate lower than that, it will start vibrating, heating up,

and in the long term the pump will experience prema-

ture failure.

A pump’s minimum flow is provided by the manufac-

turer; however, as a first, rough estimate 30–40% of the

“BEP flow rate” can be considered as the approximate

minimum flow of a centrifugal pump.

During the operation of the plant the flow rate may go

to values even lower than the minimum flow rate; how

can we protect our pump when the flow rate goes below

the minimum flow rate of our pump? To protect the

pump from flows below the minimum flow reported by

the manufacturer, a specific arrangement including a

minimum flow recirculation pipe (or “spillback”) with a

control system needs to be implemented. This system

can be called the “minimum flow protection” system.

If, for whatever reason, the flow to a pump is decreased

to a value lower than the minimum flow rate of the pump

we generally don’t have any control over increasing it if

this reduced flow rate is inevitable. What we can do is

basically a trick, and is the recirculation of a portion of

the stream around the pump to “fool” the pump into

“seeing” a flow rate higher than its minimum flow rate.

It is important to know that by recirculation of flow

around the centrifugal pump we just increase the flow

rate in one circle and include the pump but this trick

doesn’t increase the flow rate beyond the recirculation

loop, it’s upstream or it’s downstream. This technique is

named the “minimum flow protection pipe” or “minimum

flow recirculation pipe” or “minimum flow spillback.”

Now that we have learned that by recirculation we can

protect a pump against thermal and mechanical instability

during very low flow rates, a few questions should be

answered to be able to implement this trick.

The four questions that should be answered to be able

to implement a spillback system on a centrifugal pump

are:

1) In which pumps do we need to implement a recircula-

tion loop?

2) Where should we position the recirculation pipe?

3) What should be the destination point of the recircula-

tion pipe?

4) What should the size of recirculation pipe be?

5) What should the arrangement of the recirculation

pipe be?

We are going to answer all these questions one by one.

10.6.2.1 Which Pumps May Need a Minimum Flow Pipe [1]

From what it was mentioned about the requirement of a

minimum flow recirculation pipe one may believe that

this is necessary for all pumps. In practice quite a few

centrifugal pumps in a plant may have a recirculation

pipe. However, there are some cases that may not need a

minimum flow recirculation pipe. They are: pumps in

closed circulating systems, pumps in intermittent services,

small pumps, and pumps with a control valve on the flow

loop or valuable speed device (VSD).

Pumps in fully closed circulating systems may not

need a minimum flow pipe. The reason is that flow in

completely closed circulating systems doesn’t change. In

such systems there is no flow‐in or flow‐out and there-

fore flow is always constant. If flow is constant why

should we put a minimum flow pipe to protect the pump

against very low flows? Examples of such systems are hot

water systems for HVAC purposes (heating, ventilation,

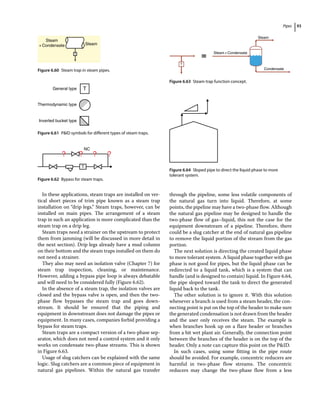

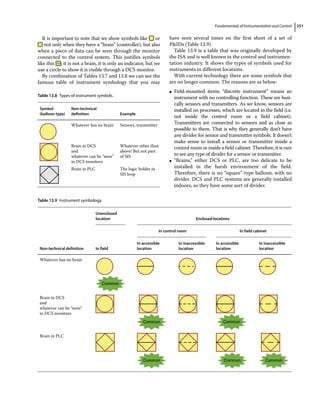

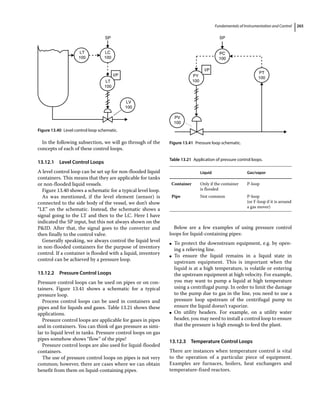

Temporary/permanent

strainer

PG for rounding

checks

To prevent

backward

rotation

As close as possible to pump

Isolation valves w/blinds

If suction flange is two

sizes smaller

PG

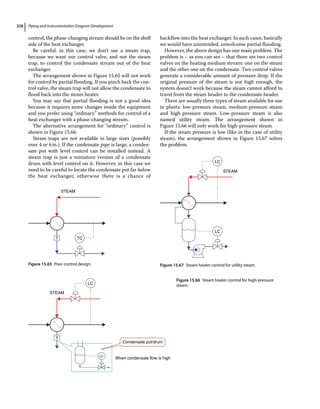

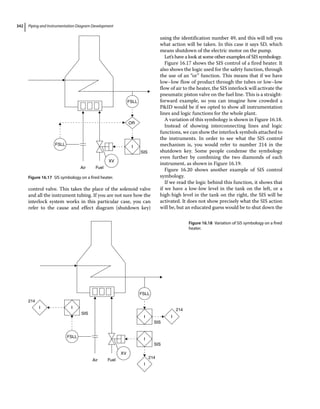

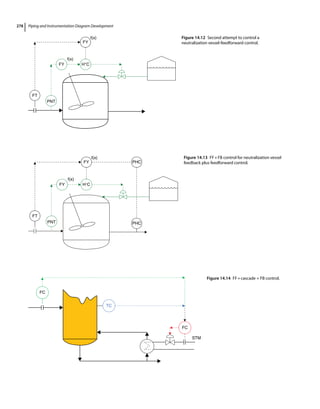

TSS

PG

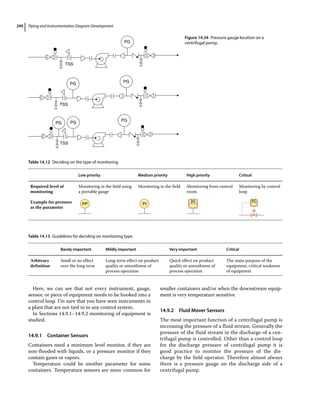

Figure 10.5 PID representation of a centrifugal pump.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pipingandinstrumentationdiagramdevelopment-230302184324-9a1d2221/85/Piping-and-Instrumentation-Diagram-Development-pdf-194-320.jpg)

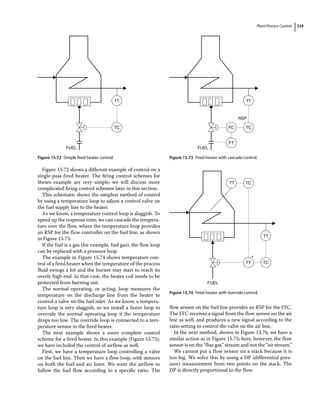

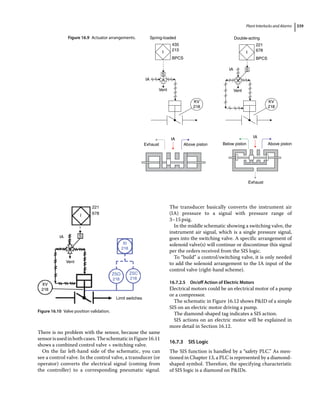

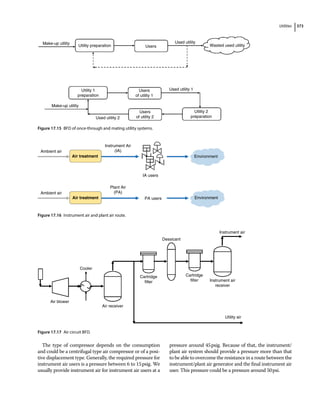

![Piping and Instrumentation Diagram Development

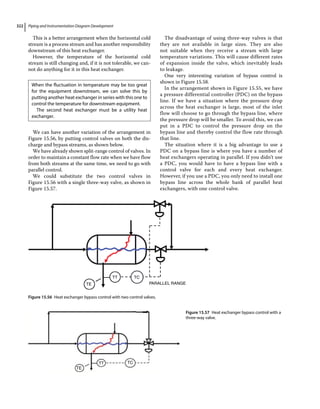

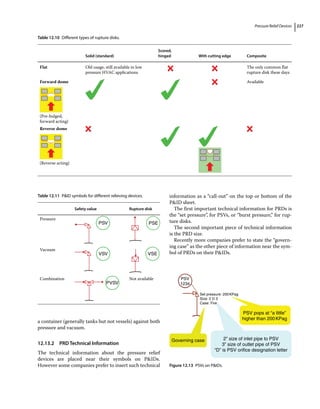

226

the functionality of the spring. The other feature of a bel-

lows‐type pressure relief valve is that the pressure down-

stream of the relief valve (or backpressure) doesn’t

impact the set pressure of the relief valve. Pilot‐type

relief valves also have this feature.

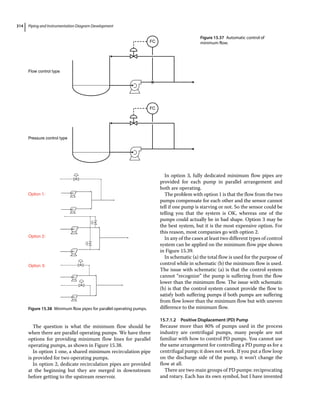

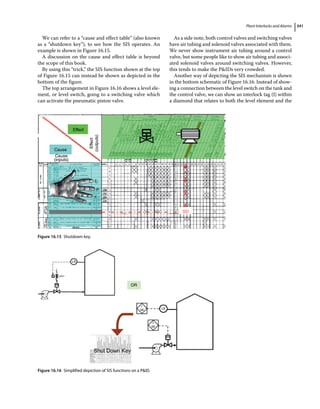

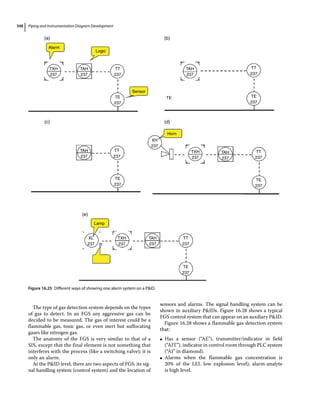

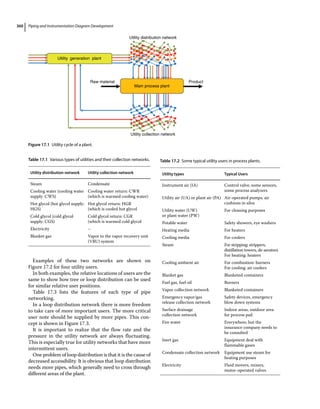

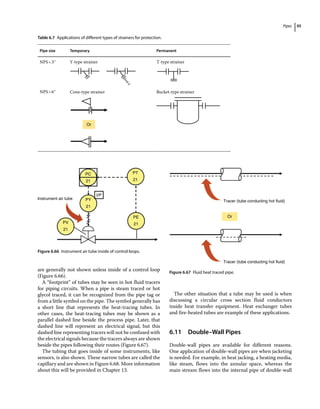

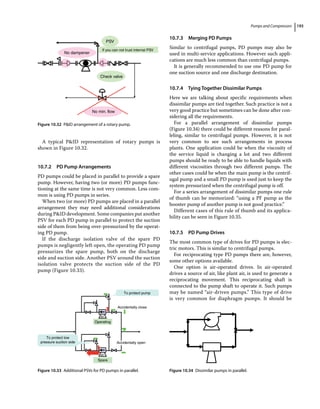

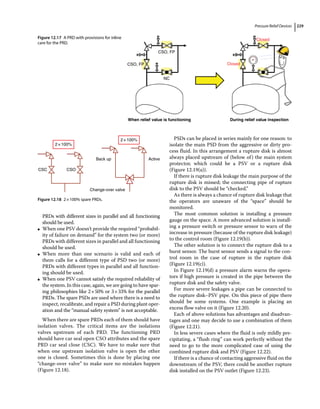

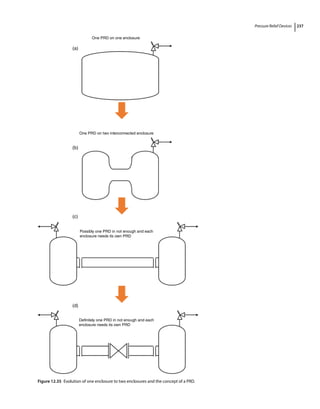

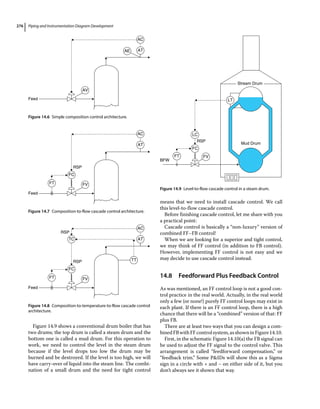

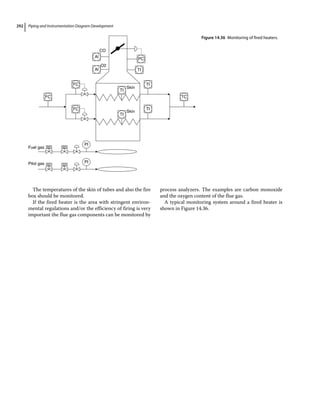

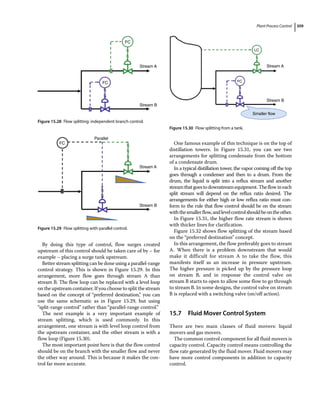

Schematics of the different types of PRDs are depicted

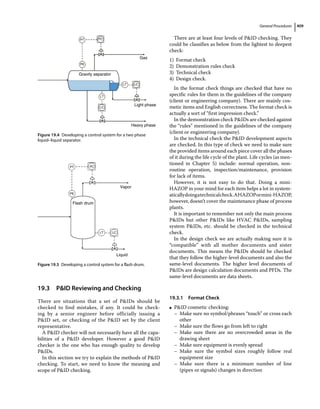

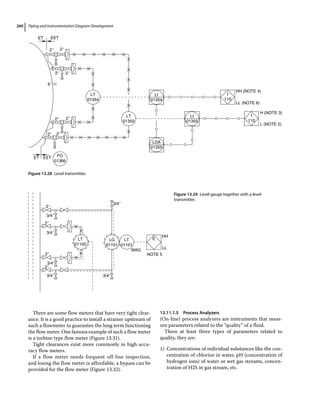

in Figure 12.12.

12.12.2 Rupture Disks

There are two types of non‐reclosable PRDs. In “rupture

disks,” a “hole” is covered by a disk that will rupture at a

specific pre‐set pressure, and release the pressure. The sec-

ond type of non‐reclosable PRDs is very similar to a spring‐

loaded PRV, but the spring is replaced by a “buckling/

breaking” pin. Between these two non‐reclosable PRDs,

rupture disks are more common.

Rupture disks are manufactured in main three forms:

flat, forward dome, and backward dome. These three

types of rupture disks could be in the form of a solid

sheet, a hinged or scored sheet, with a cutting edge, and

in composite. The available types of rupture disks are

shown in Table 12.10.

12.12.3 Decision General Rules

Deciding on PSD types are based on quantitative and

qualitative parameters. As many criteria go back to the

design stage of project, they are not discussed here.

12.13 PRD Identifiers

As it was stated in Chapter 4, the identifiers of PRDs – as

an item of instrumentation – on PIDs are PRD sym-

bols, PRD tags, and PRD technical information.

12.13.1 PRD Symbols and Tags

Table 12.11 shows P/V RD symbols and tags.

As can be seen in the table, when there is a need to

have both a pressure relief valve and a vacuum relief

valve, these two devices can be merged together to save

money on nozzles and other operating costs. The PVSV

was invented for this purpose. PVSVs (pressure/vacuum

safety valves, or as some companies call them, PVRVs

[pressure/vacuum relief valves]) are devices that protect

Inlet connection

Conventional type

Spring-type

Schematic

Dead weight-type Pilot-type

Outlet

connection

Inlet connection

Balance type

Outlet

connection

Inlet connection Inlet connection

Outlet

connection

Outlet

connection

Figure 12.12 Different types of relief valves.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pipingandinstrumentationdiagramdevelopment-230302184324-9a1d2221/85/Piping-and-Instrumentation-Diagram-Development-pdf-244-320.jpg)

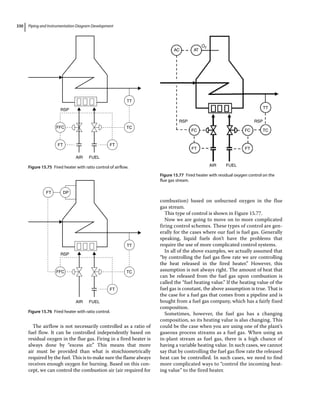

![Piping and Instrumentation Diagram Development

312

Control Valve Versus VFD

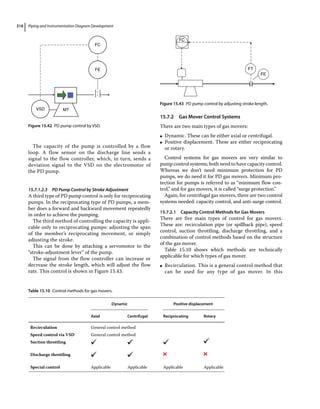

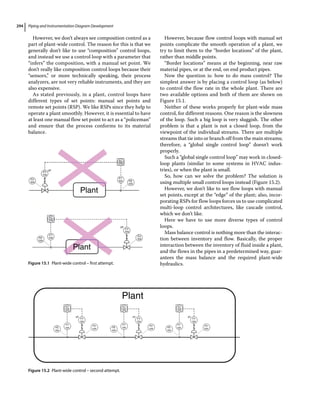

We learned that there are at least two methods of con-

trolling pumps: by control valve and by VFD. Now the

question is, which one should be used? Sometimes when

we are not sure, we use both of them in the form of split‐

range control. If we cannot afford to use both of them (in

the form of split control), we need to choose one of them.

Traditionally, we use a control valve because it is an older

technology; however, there are cases where a VFD works

better.

The main consciously changing parameter in a water

treatment plant is the flow rate. The flow rate is changing

and we have to find “something” to adjust the flow rate of

different pieces of equipment.

There are mainly two types of device can be used to

adjust the flow rate: control valve and VSD.

A control valve is generally installed on the discharge

line of a pump (or compressor) and the VSD is installed

on the electromotor of the pump (or compressor).

These two methods of adjusting flow rates are named

“final control elements.”

These two methods of controlling the flow rate are

very similar to two methods of controlling the speed of

car we are driving. This analogy can be seen below.

Table 15.9 summarizes some process reasons for using

a control valve or a VFD.

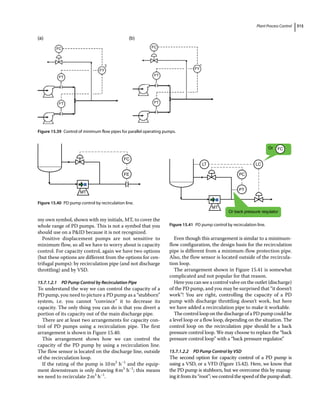

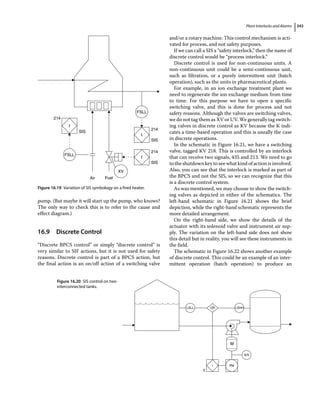

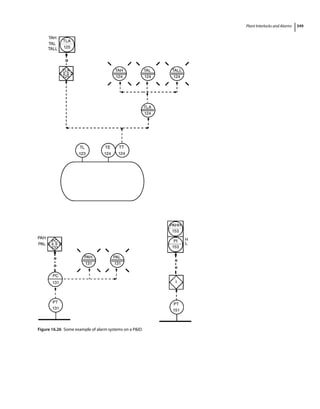

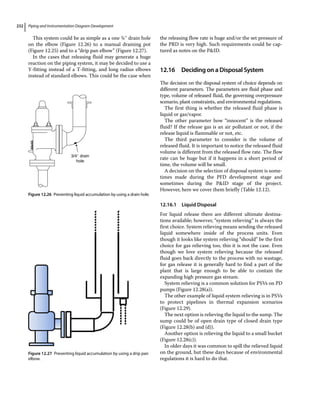

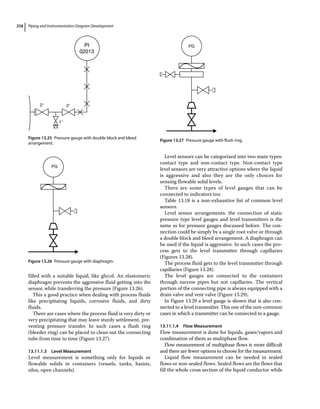

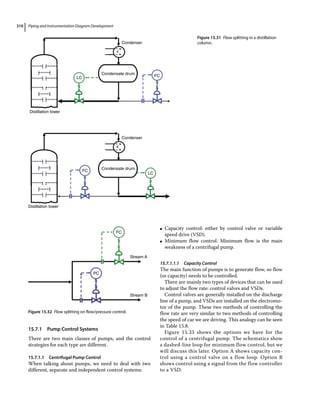

15.7.1.1.2 Minimum Flow Control

The concept of minimum flow control is shown in

Figure 15.34. Let’s assume that this pump has a capacity

of 200m3

h−1

. The vendor specified that the minimum

flow rate of the pump is 100m3

h−1

. We can provide a

recirculation line from the outlet of the pump back into

the inlet line.

If the flow rate into the pump is 165m3

h−1

, the pump

is happy, since its flow is higher than the minimum flow.

In this case, the sensor on the pump outlet sends a signal

to the control valve on the recirculation line and it

remains closed. However, if the flow drops below

100m3

h−1

, for example to 80m3

h−1

, the flow sensor on

the outlet will send a signal to the controller to say: “I am

short of my minimum required flow by 20 m3

h−1

and I

am worried about the pump. Please open the valve

enough to recirculate 20 m3

h−1

, so we can fool the pump

into thinking that the flow is 100 m3

h−1

, and make it

happy,” The control valve on the recirculation line will

be partially opened to provide a flow of 20m3

h−1

, which

is sent back to the inlet to satisfy the minimum flow

condition of 100m3

h−1

, and prevent damage to the

pump. This is the concept of minimum flow control.

It is important to recognize that this “trick” only

increases the flow rate inside the recirculation loop to a

number higher than 100m3

h−1

to “fool” the pump. We

are not able to increase the overall flow in the whole

upstream and downstream piping system; the flow in

those pipes is still 80m3

hr−1

.

The point here is that the sensor should be placed as

close as possible to the pump and within the recircula-

tion loop.

Now the question is whether we need a minimum flow

control loop for all centrifugal pumps or not. The answer

is no! We don’t need minimum flow control loop for all

centrifugal pumps.

The following examples of pumps may not need a min-

imum flow control loop [1]:

●

● Small pumps of less than 5hp; they need it, but they

are inexpensive so we don’t bother to put an expensive

minimum flow control loop on them.

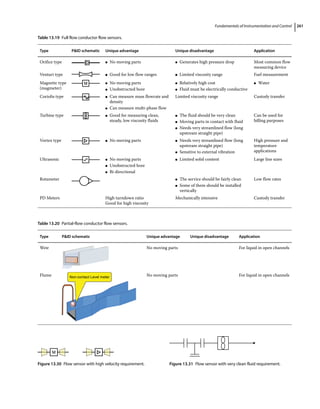

FC

Option A

Option B

FC

FC

FC

VSD

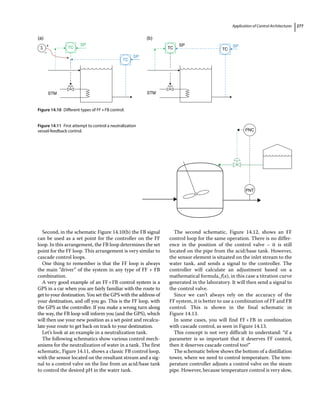

Figure 15.33 Options for centrifugal pump capacity control.

Table 15.9 Options for centrifugal pump capacity control.

Control valve VFD

●

● Generates more shear on the

stream. Not good for shear‐

sensitive liquids like oily

waters, biomaterial, water

carrying flows etc.

●

● Works for all types of piping

circuits

●

● Generates less shear on

the stream

●

● Doesn’t work in systems

where the majority of the

pump head is used to

overcome static pressure

rather than pipe pressure

loss](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pipingandinstrumentationdiagramdevelopment-230302184324-9a1d2221/85/Piping-and-Instrumentation-Diagram-Development-pdf-328-320.jpg)