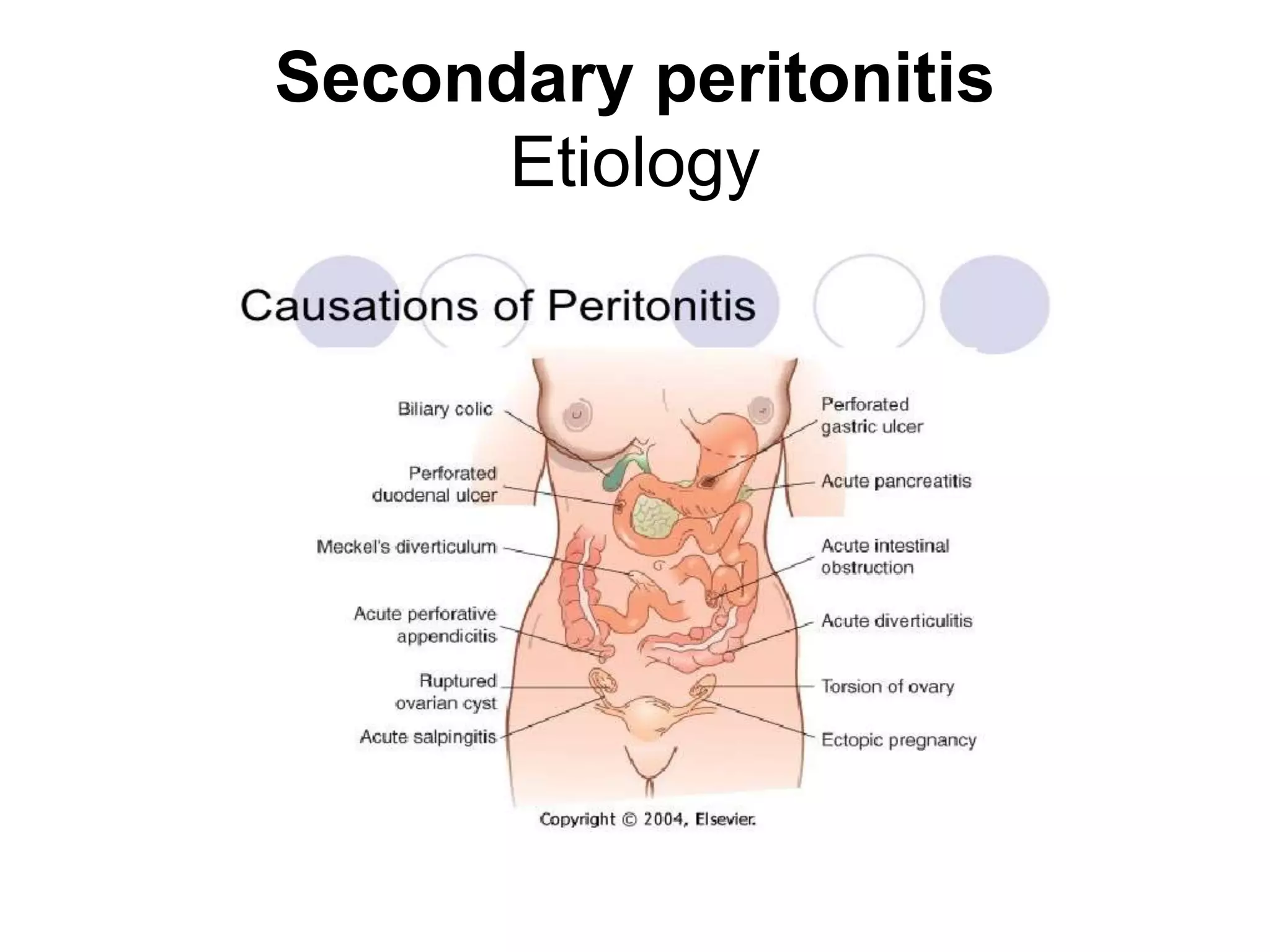

Peritonitis is an inflammation of the peritoneum that can be caused by infections spreading from the gastrointestinal tract or other abdominal organs. There are two main types - primary peritonitis arising from the peritoneum itself, and secondary peritonitis arising from intra-abdominal infections. Symptoms include abdominal pain and tenderness. Diagnosis involves physical exam, imaging, and diagnostic laparoscopy. Treatment focuses on treating the underlying cause, administering antibiotics, and surgically removing infected tissues or foreign bodies to control the infection.