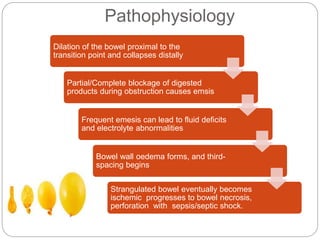

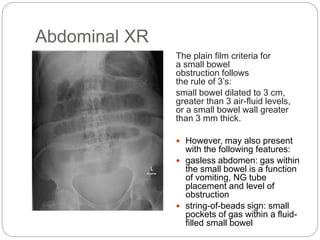

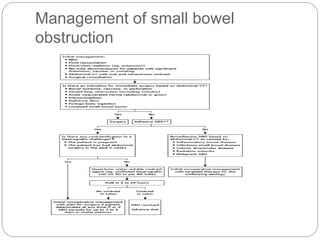

Small bowel obstruction occurs when the small bowel is blocked, preventing the normal flow of digestive contents. There are two main types - functional and mechanical. Common causes include adhesions, hernias, tumors, and ingestion of foreign bodies. Symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Diagnosis involves blood tests, abdominal x-rays to detect air-fluid levels, and CT scanning to identify the level and cause of obstruction. Treatment focuses on resuscitation, bowel decompression via nasogastric tube, and surgical intervention if needed to remove the obstruction. Early diagnosis and treatment are important to prevent complications like strangulation and perforation which can increase mortality.

![Outcomes

The morbidity and mortality of bowel obstruction are

dependent on early diagnosis and management.

If any strangulated bowel is left untreated, there is a

mortality rate of close to 100%.

However, if surgery is undertaken within 24-48 hours,

the mortality rates are less than 10%.

Factors that determine the morbidity include the age

of patient, comorbidity, and delay in treatment. Today,

the overall mortality of bowel obstruction is still about

5%-8%.[3][10] [Level 3]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/smallbowelobstructionpresentation-221106125258-a3135ec8/85/Small-Bowel-obstruction-presentation-pptx-14-320.jpg)