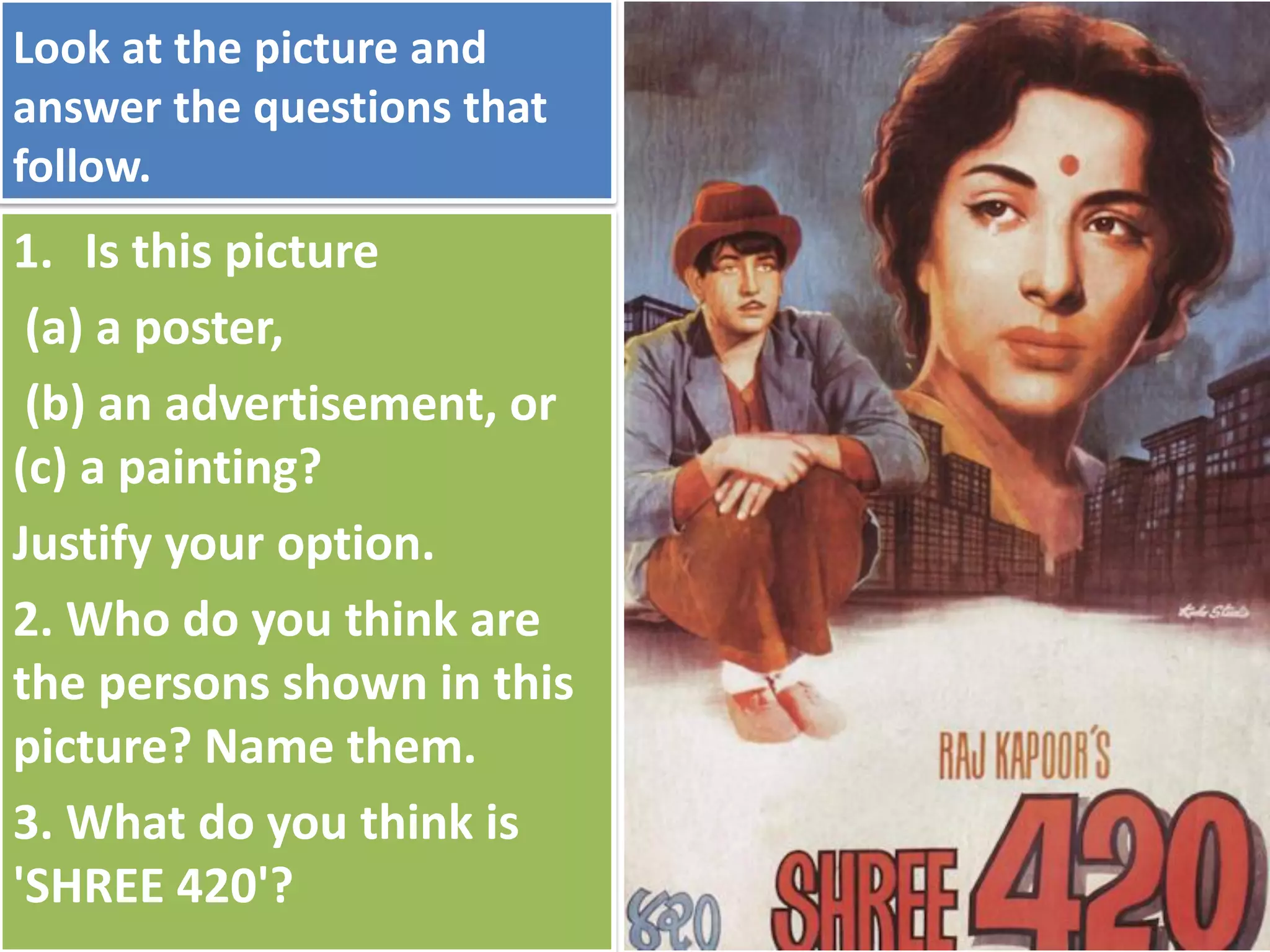

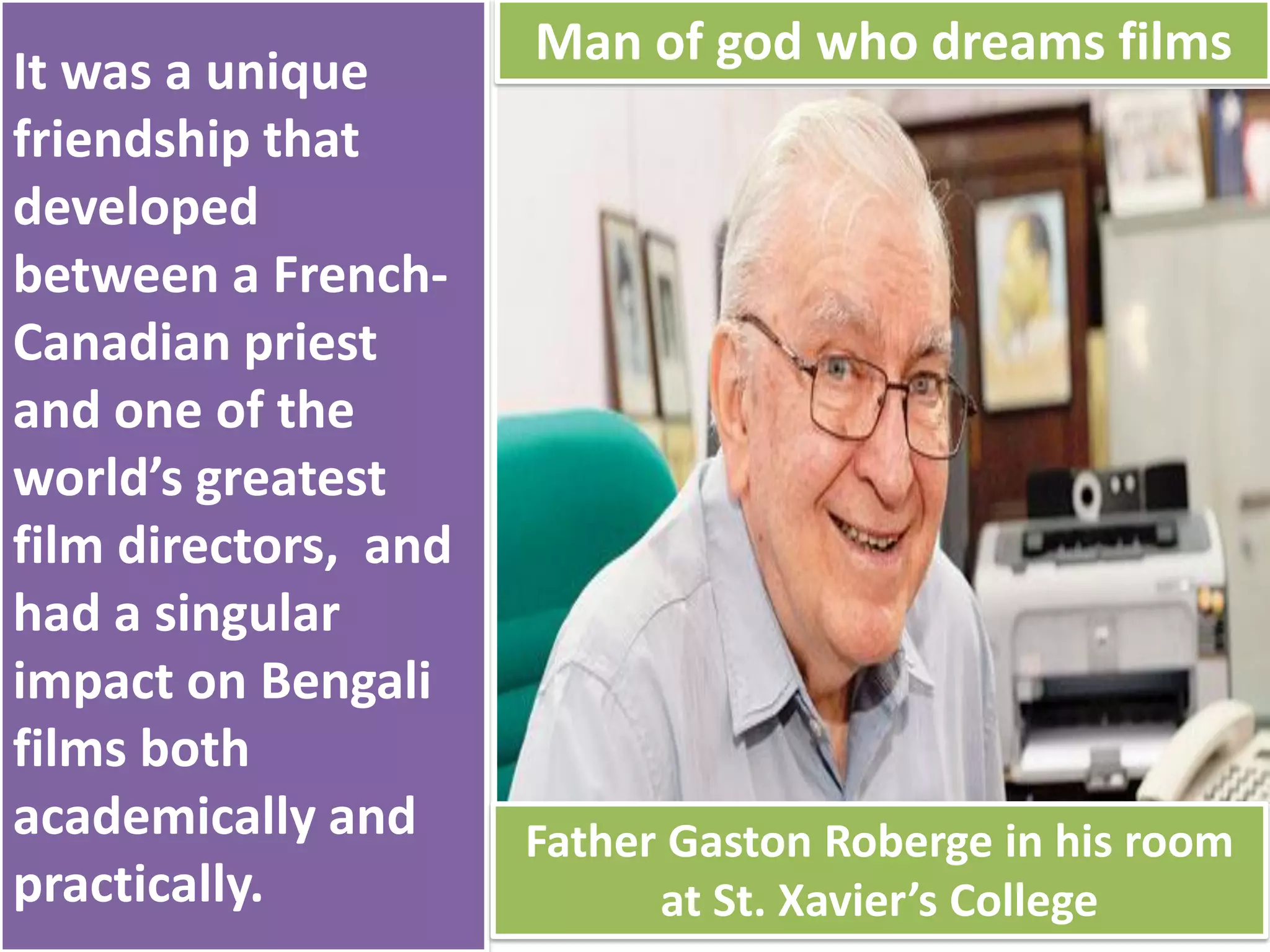

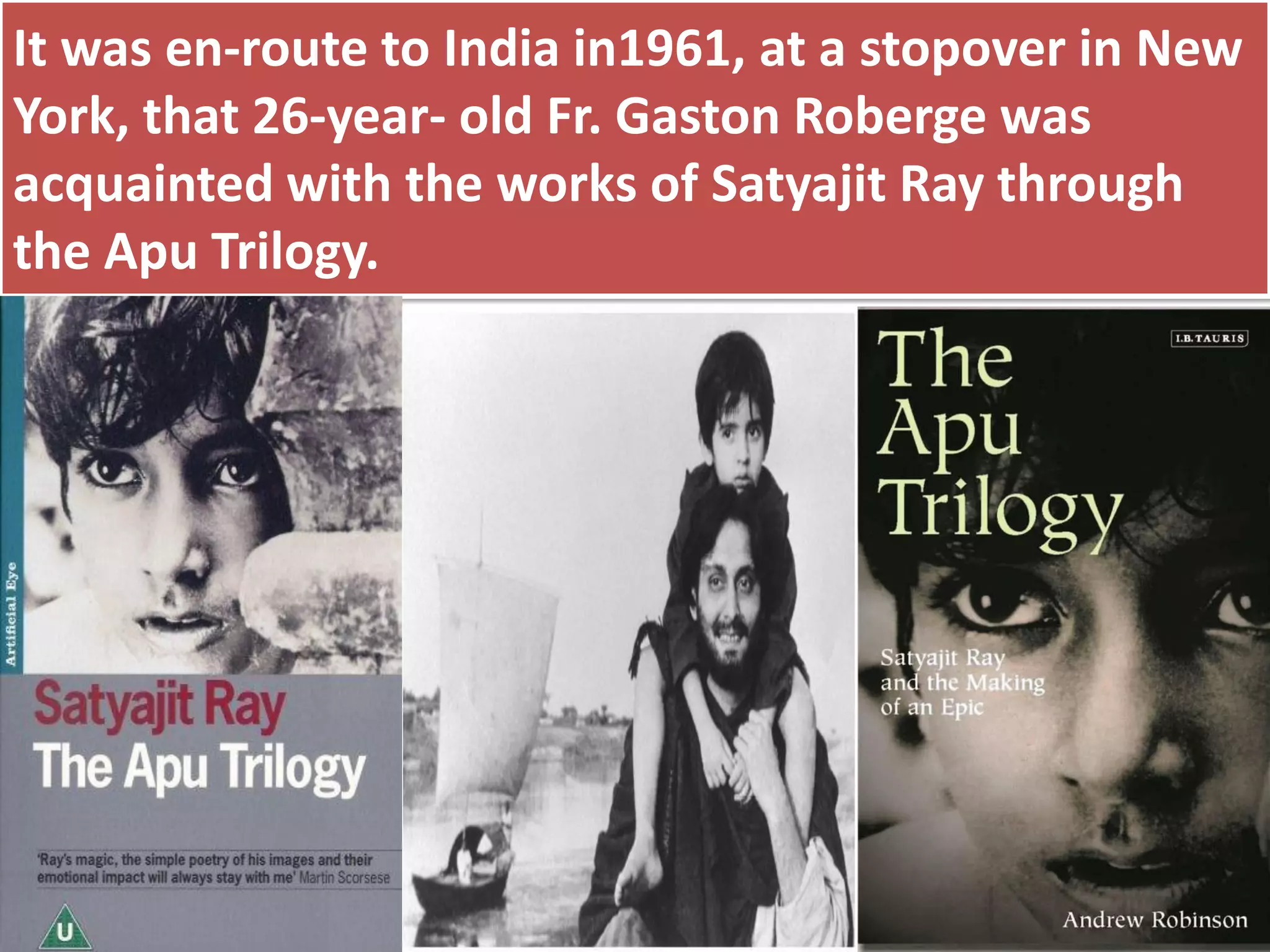

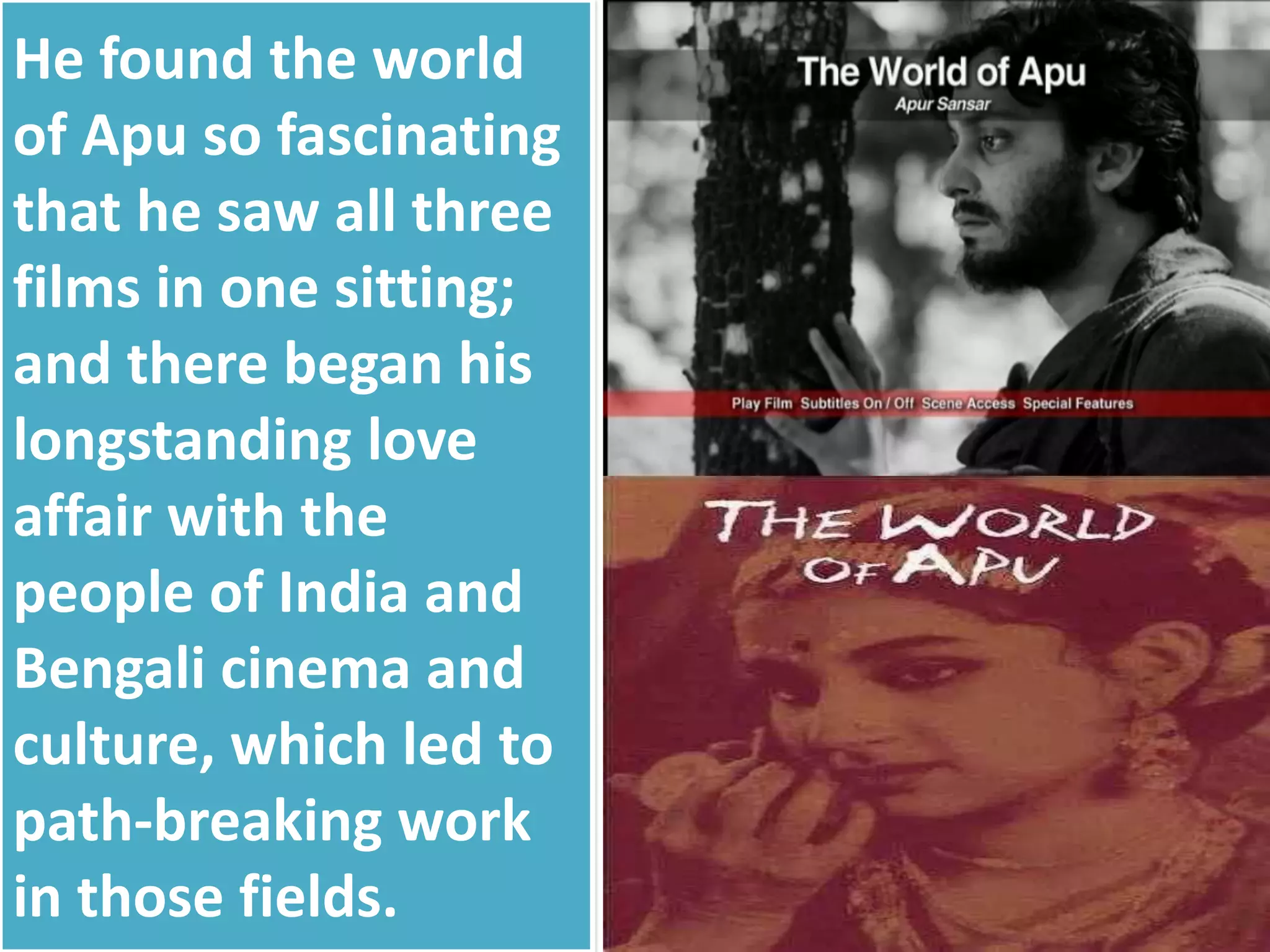

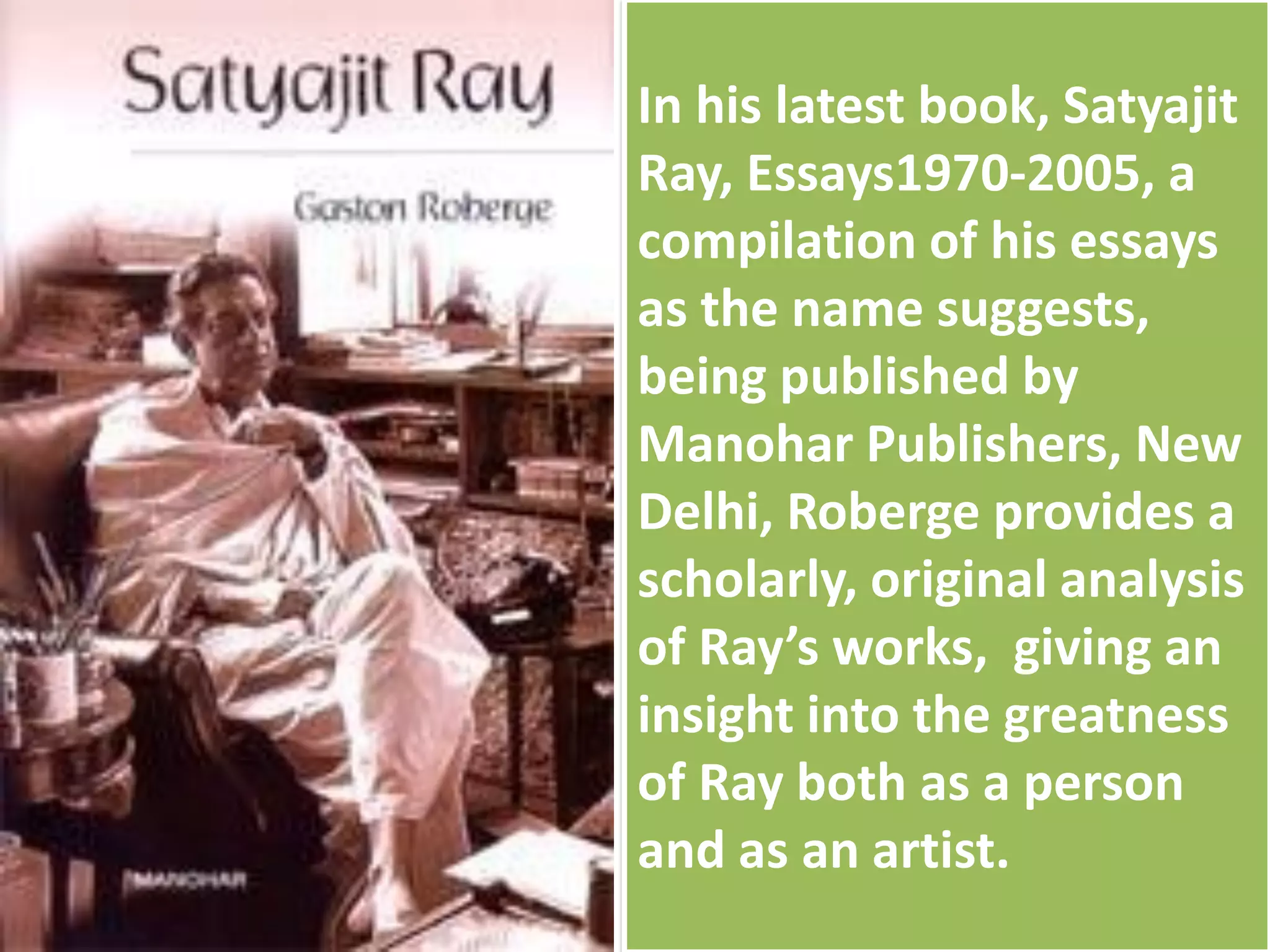

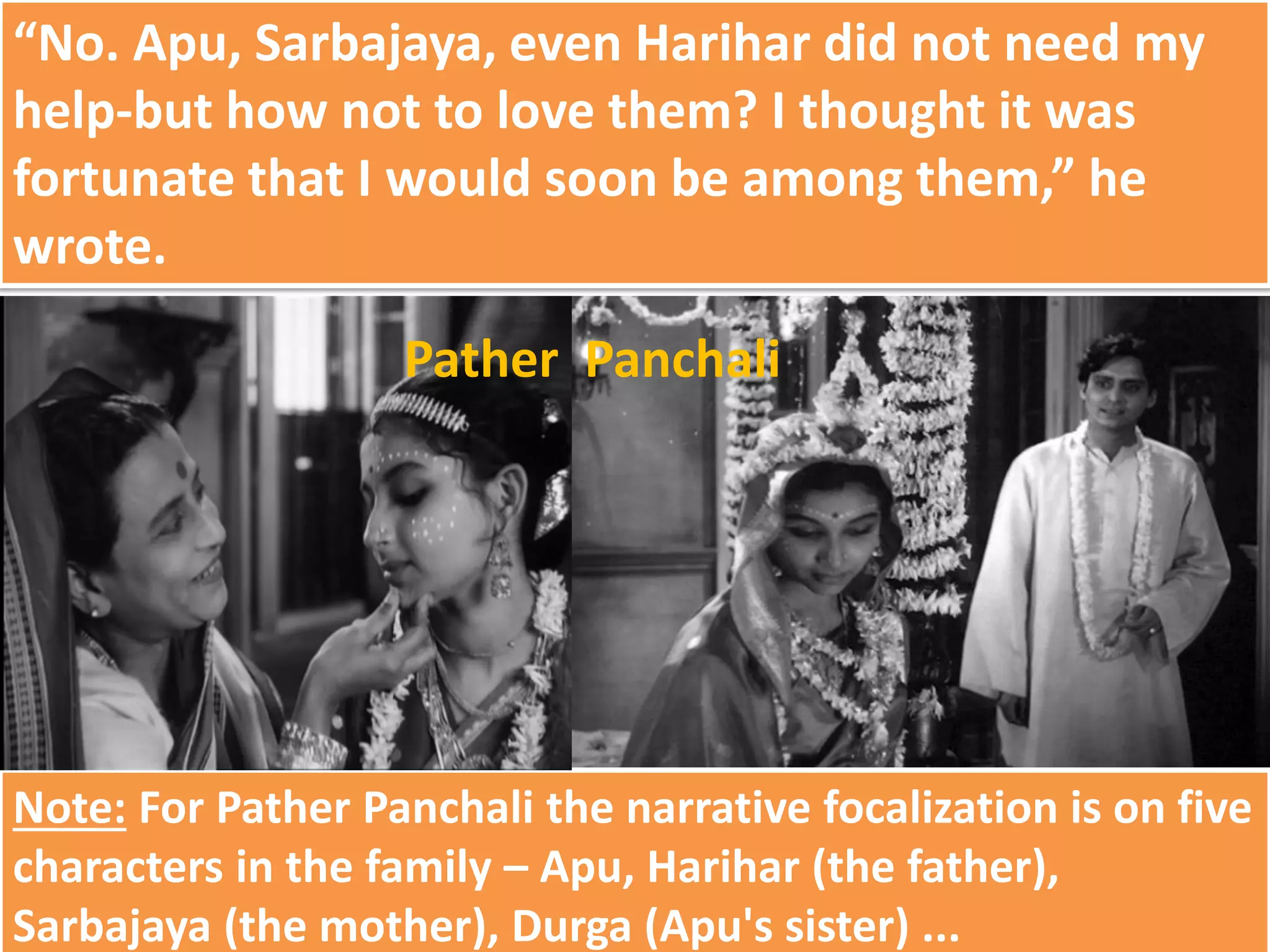

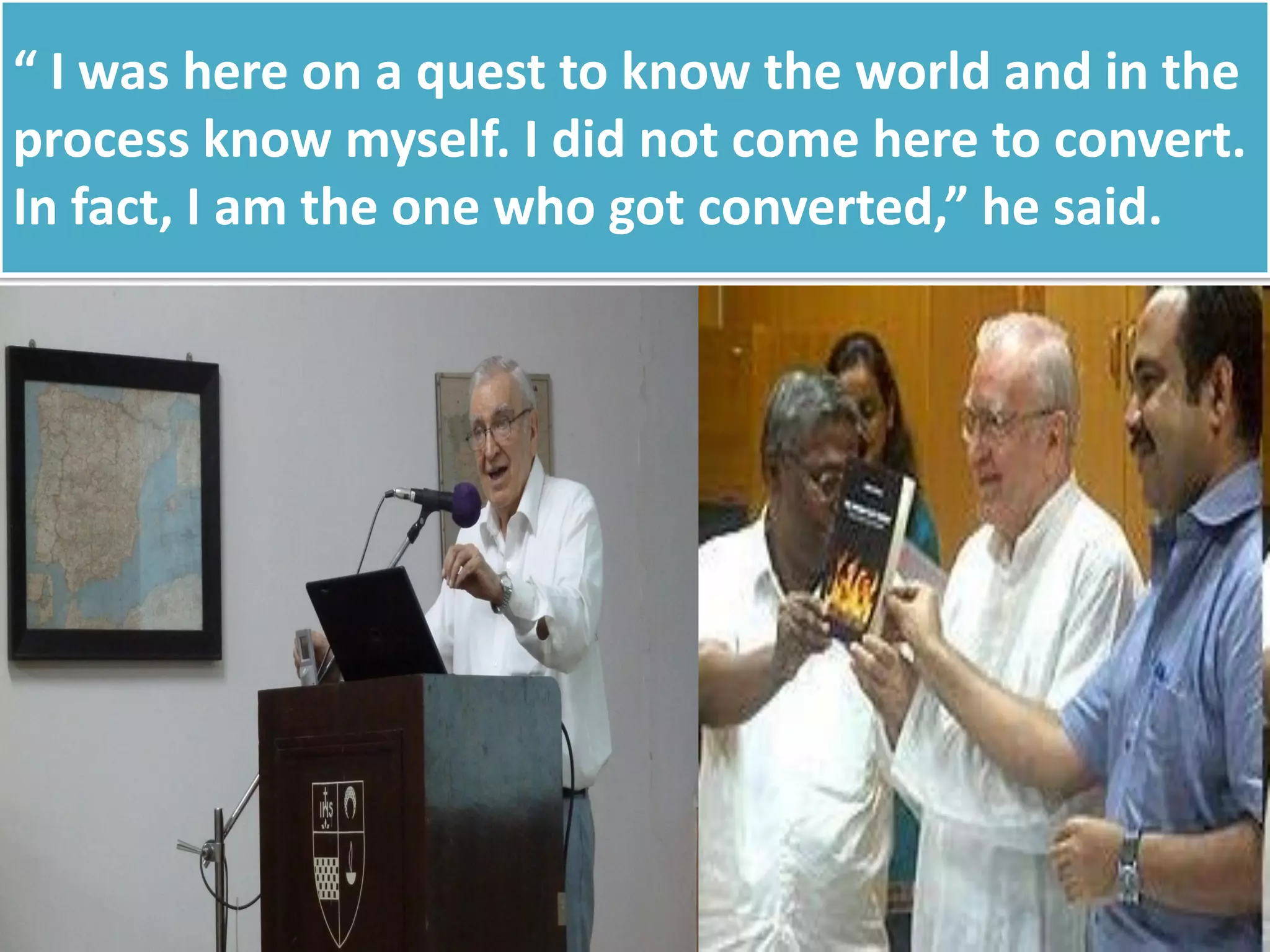

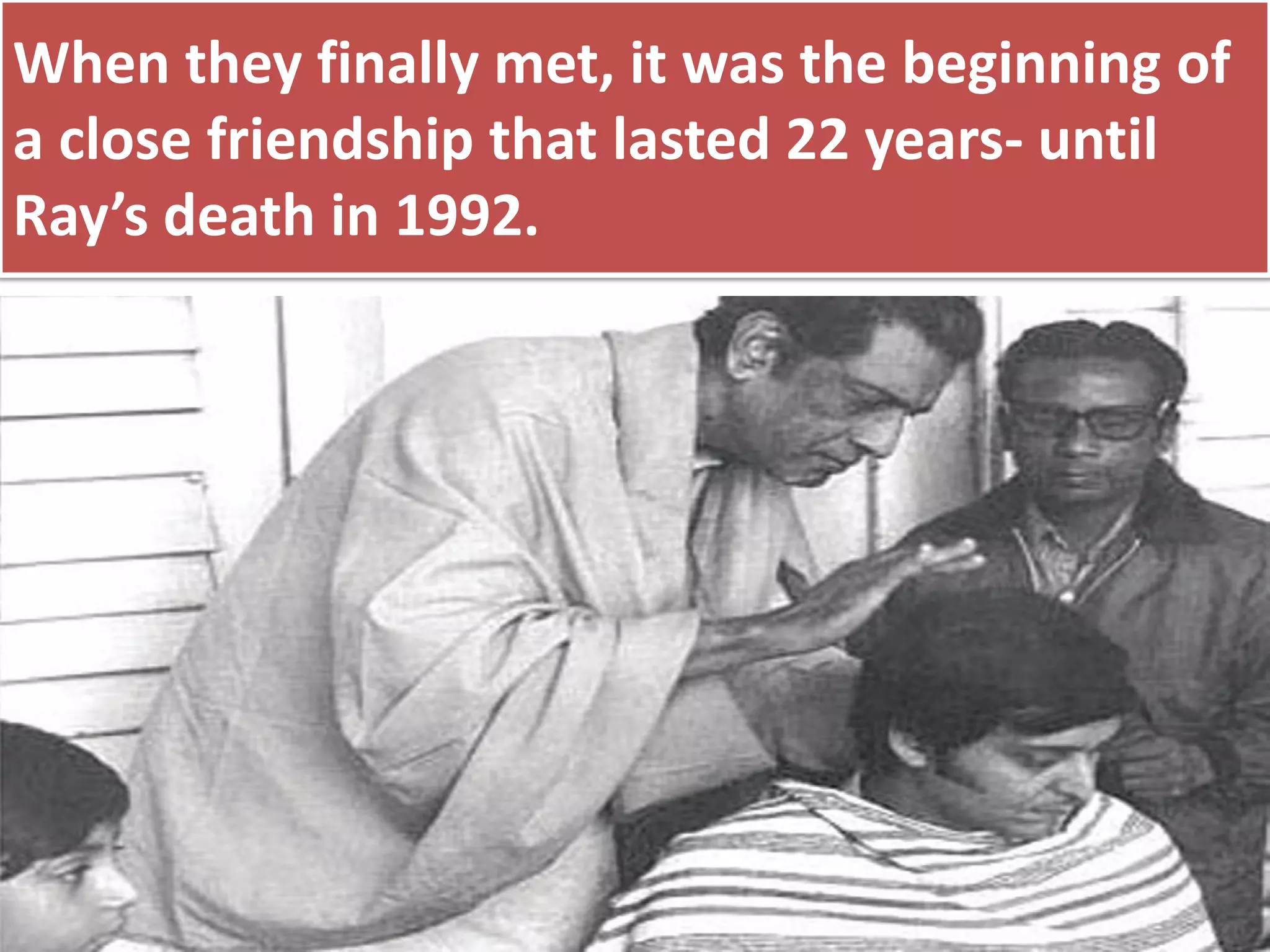

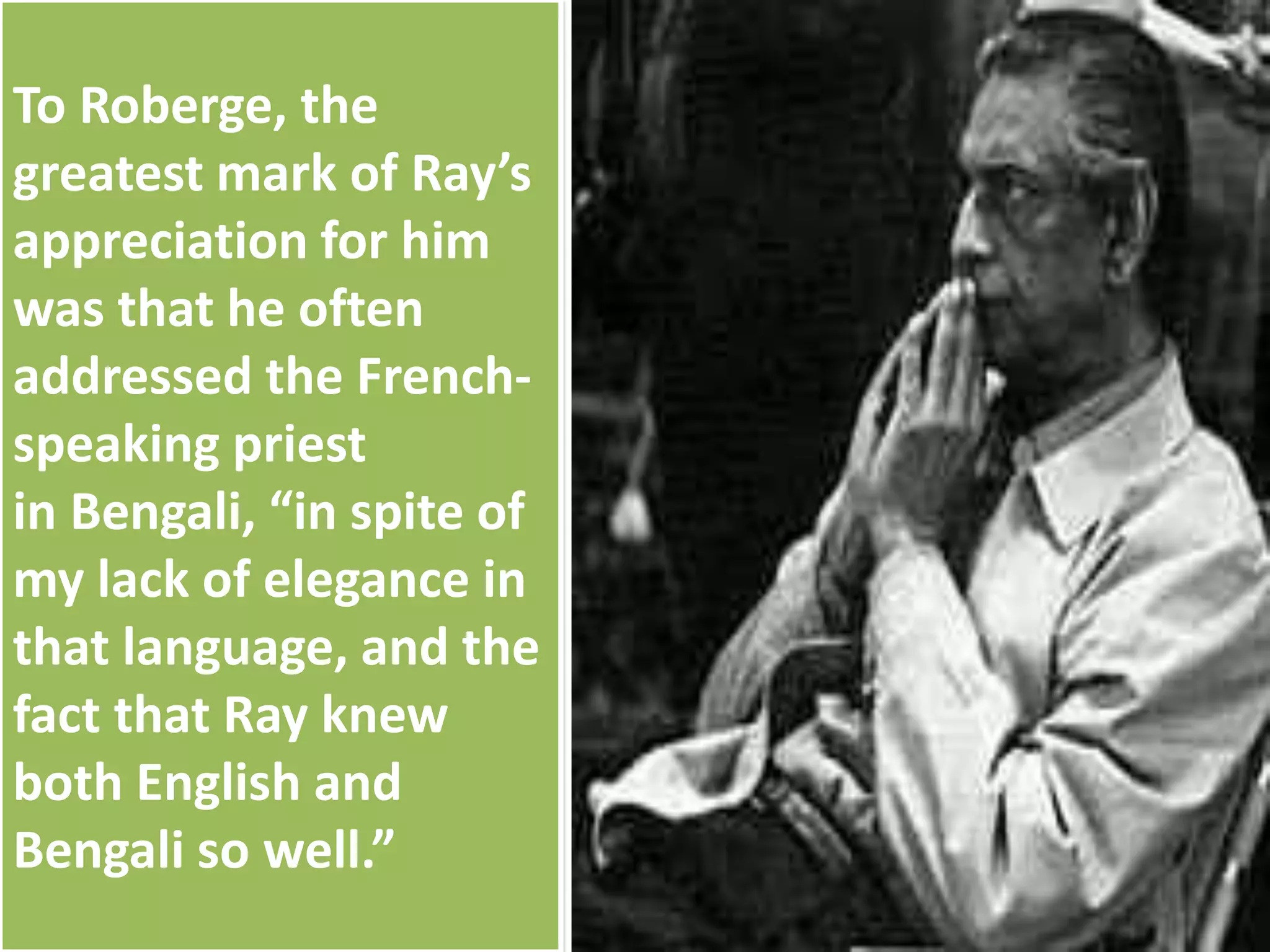

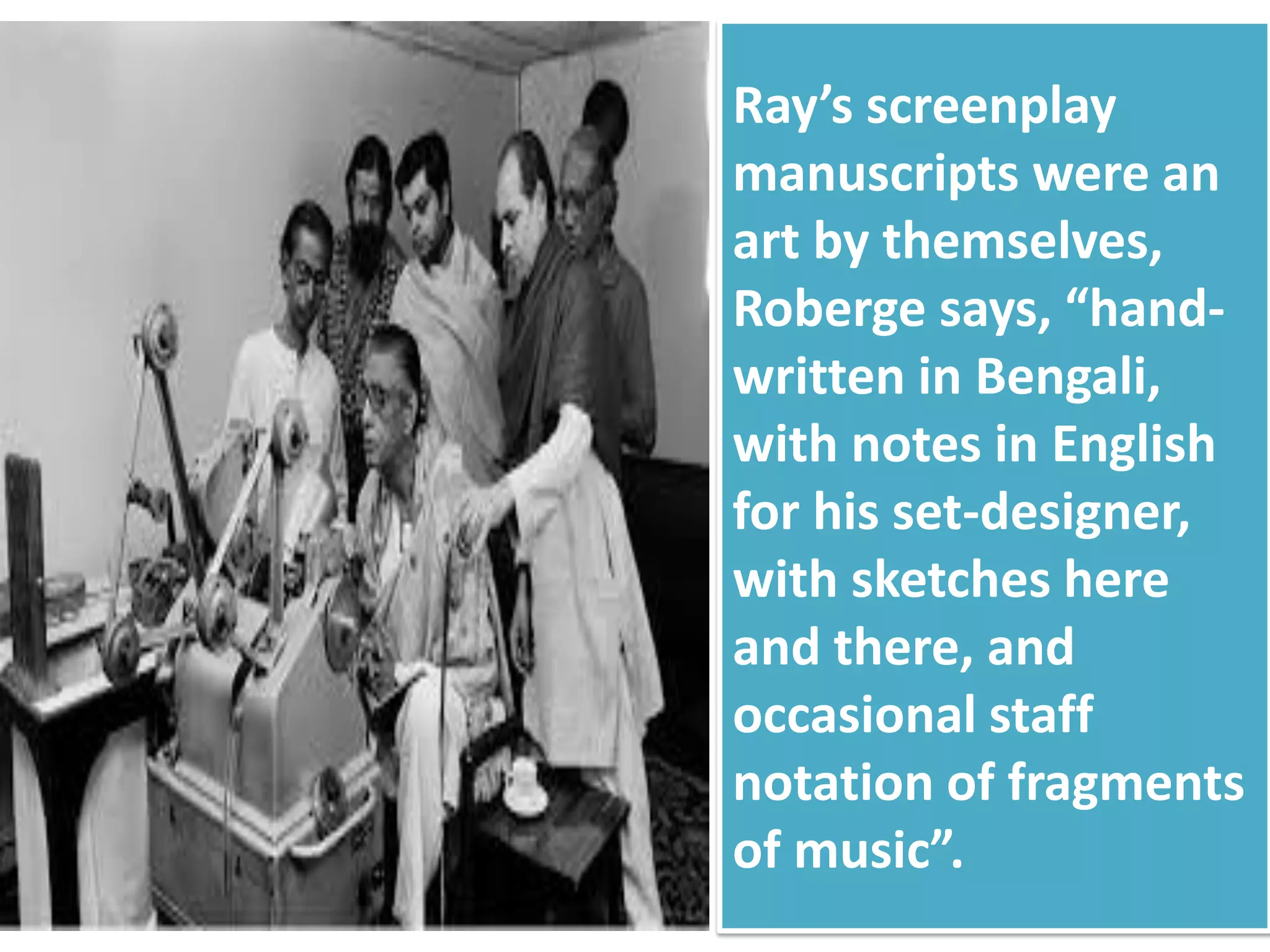

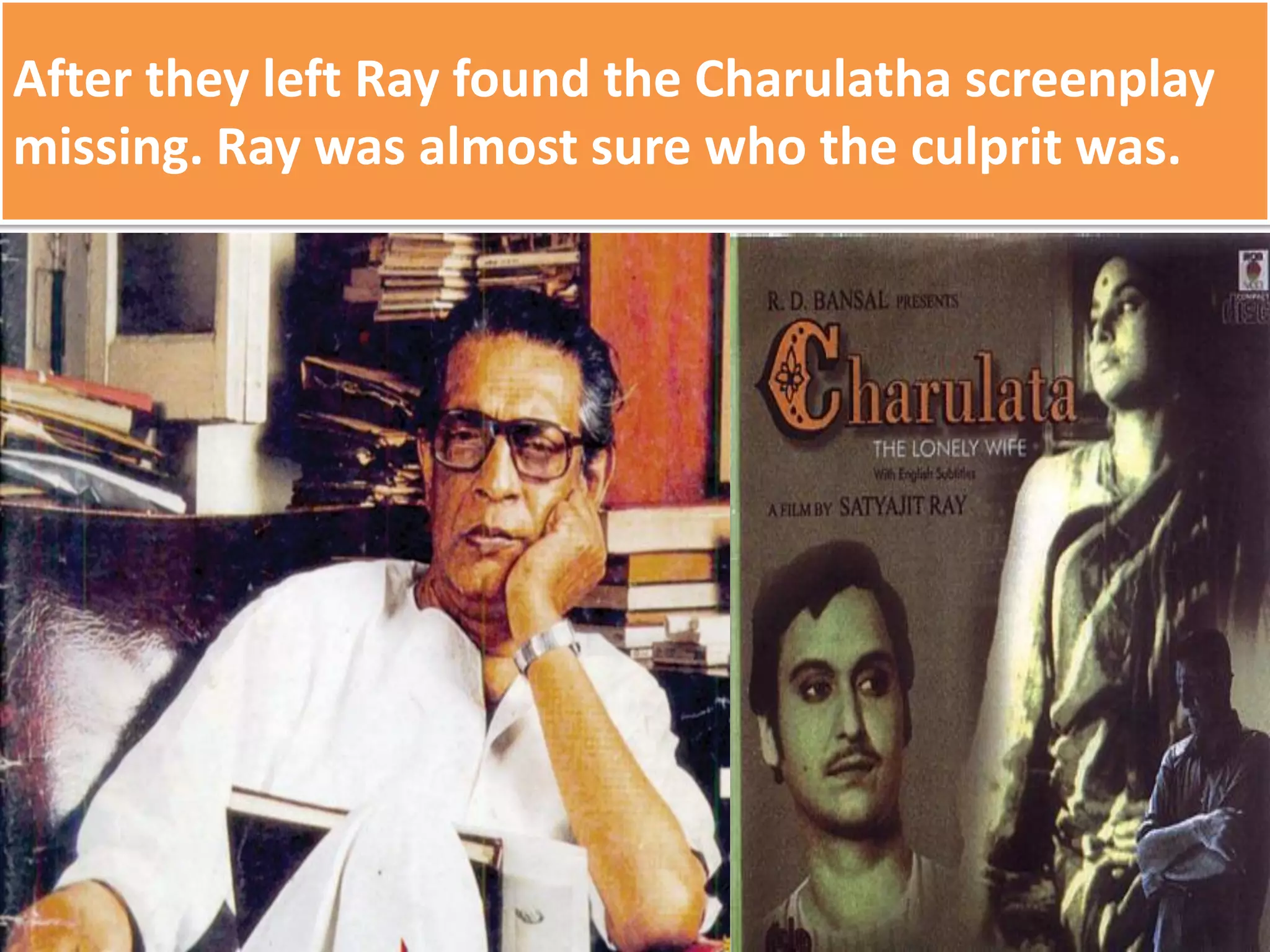

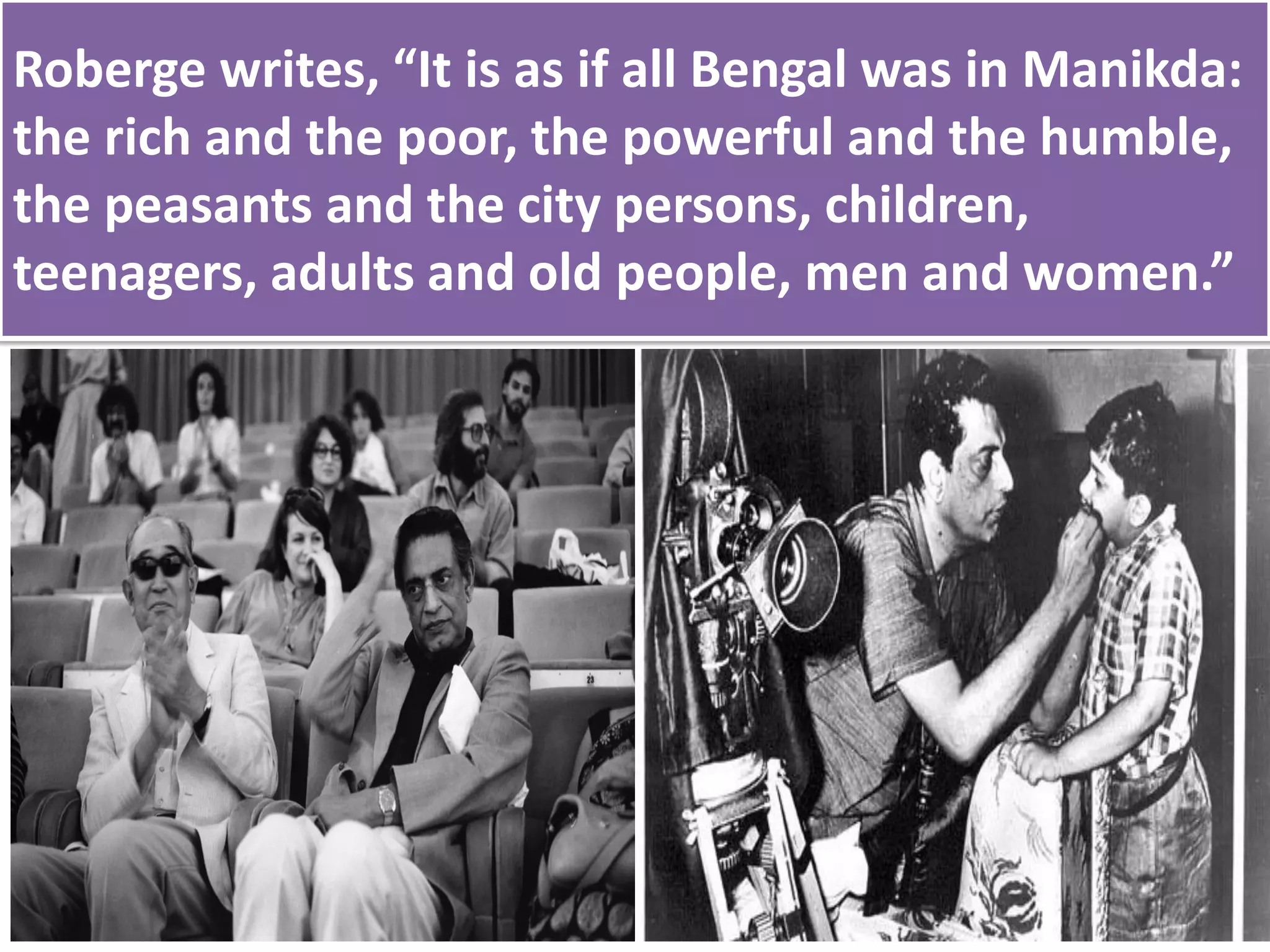

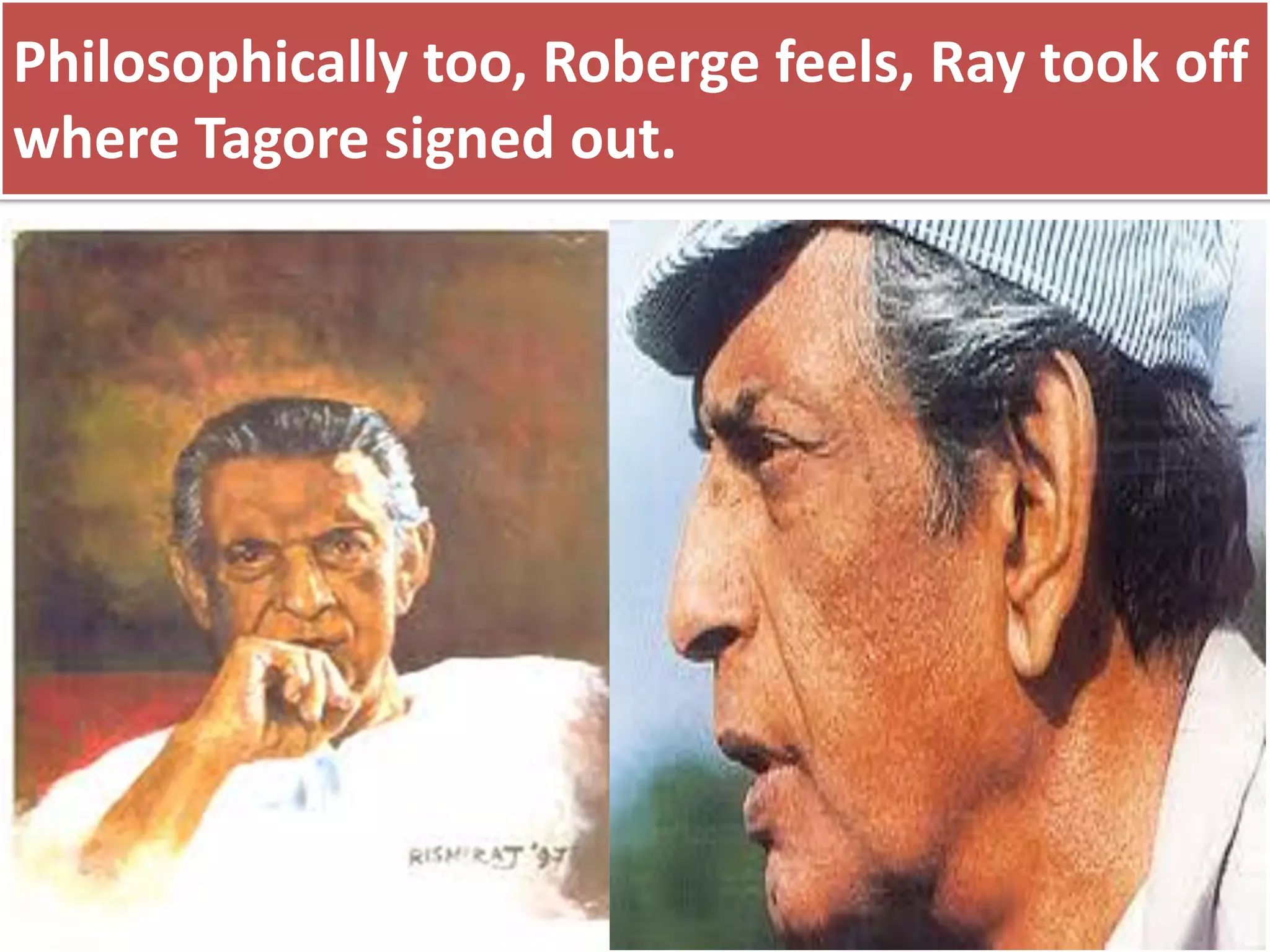

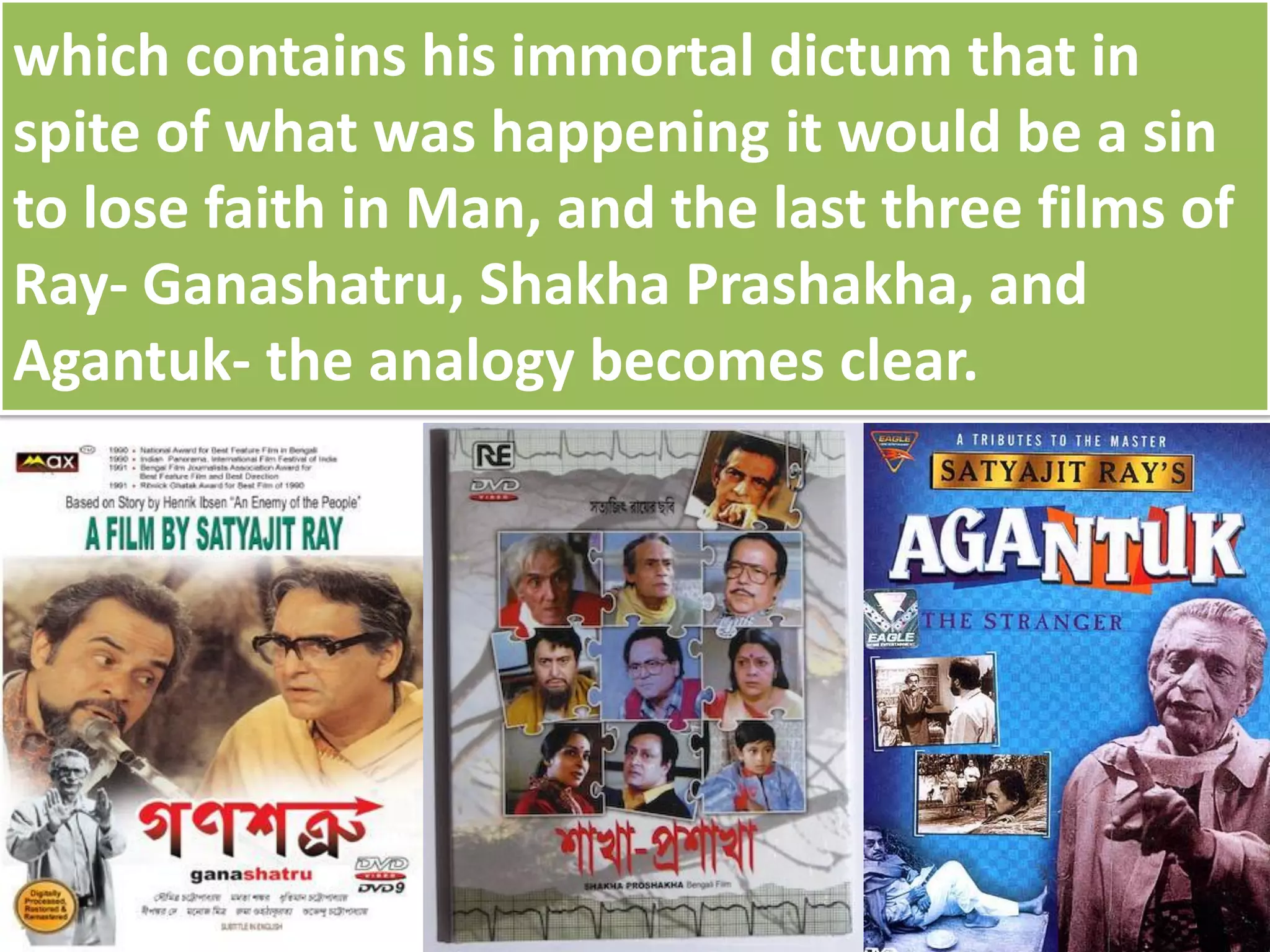

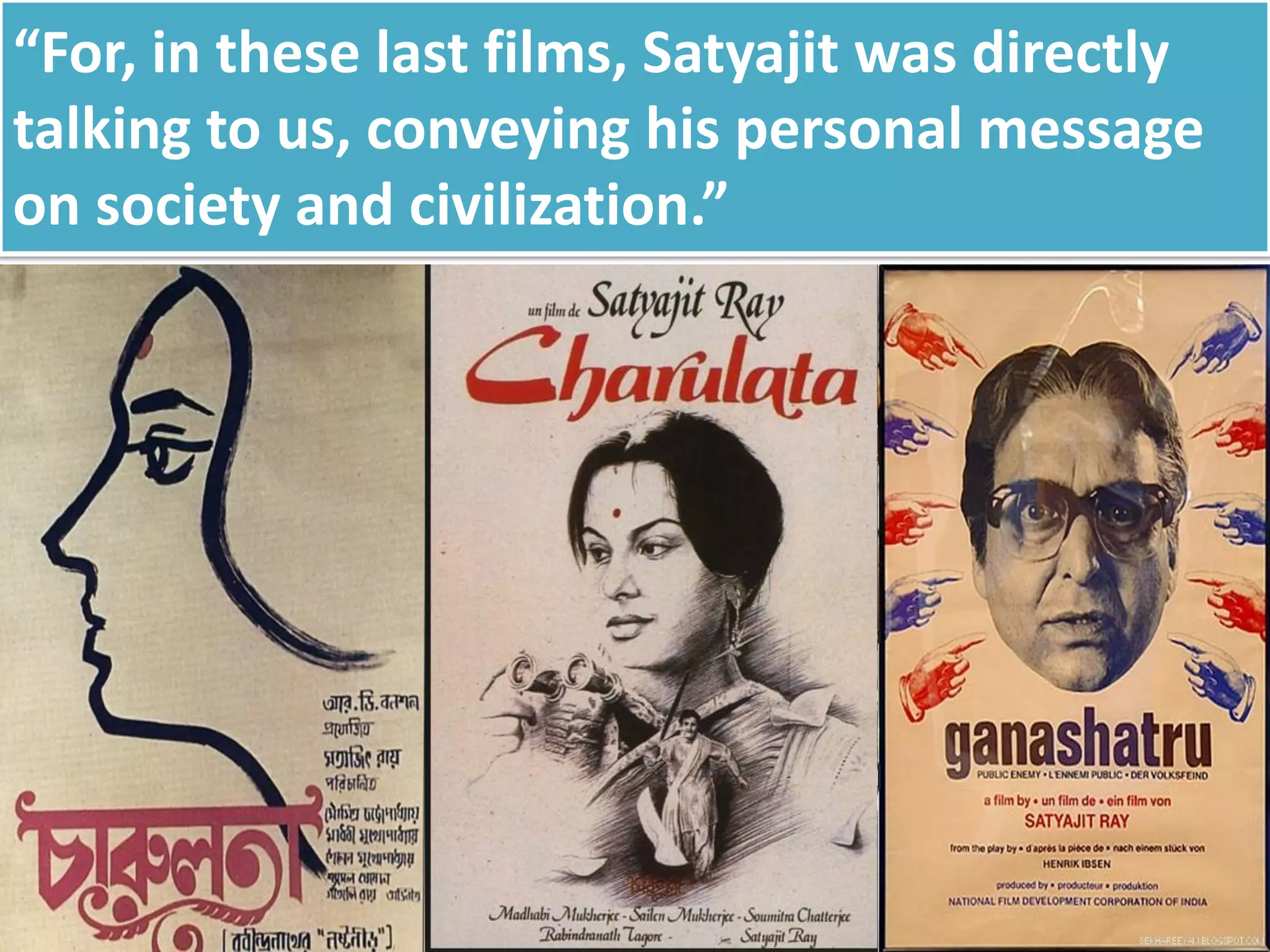

This document details the unique friendship between Fr. Gaston Roberge and filmmaker Satyajit Ray, highlighting their influential connection through Bengali cinema. Roberge, who arrived in India in 1961, became a scholar of Ray's work and eventually co-founded Chitrabani, a film institute in West Bengal. The narrative captures their deep bond over 22 years, ending with Ray's last moments and Roberge's reflections on Ray's contributions to art and society.

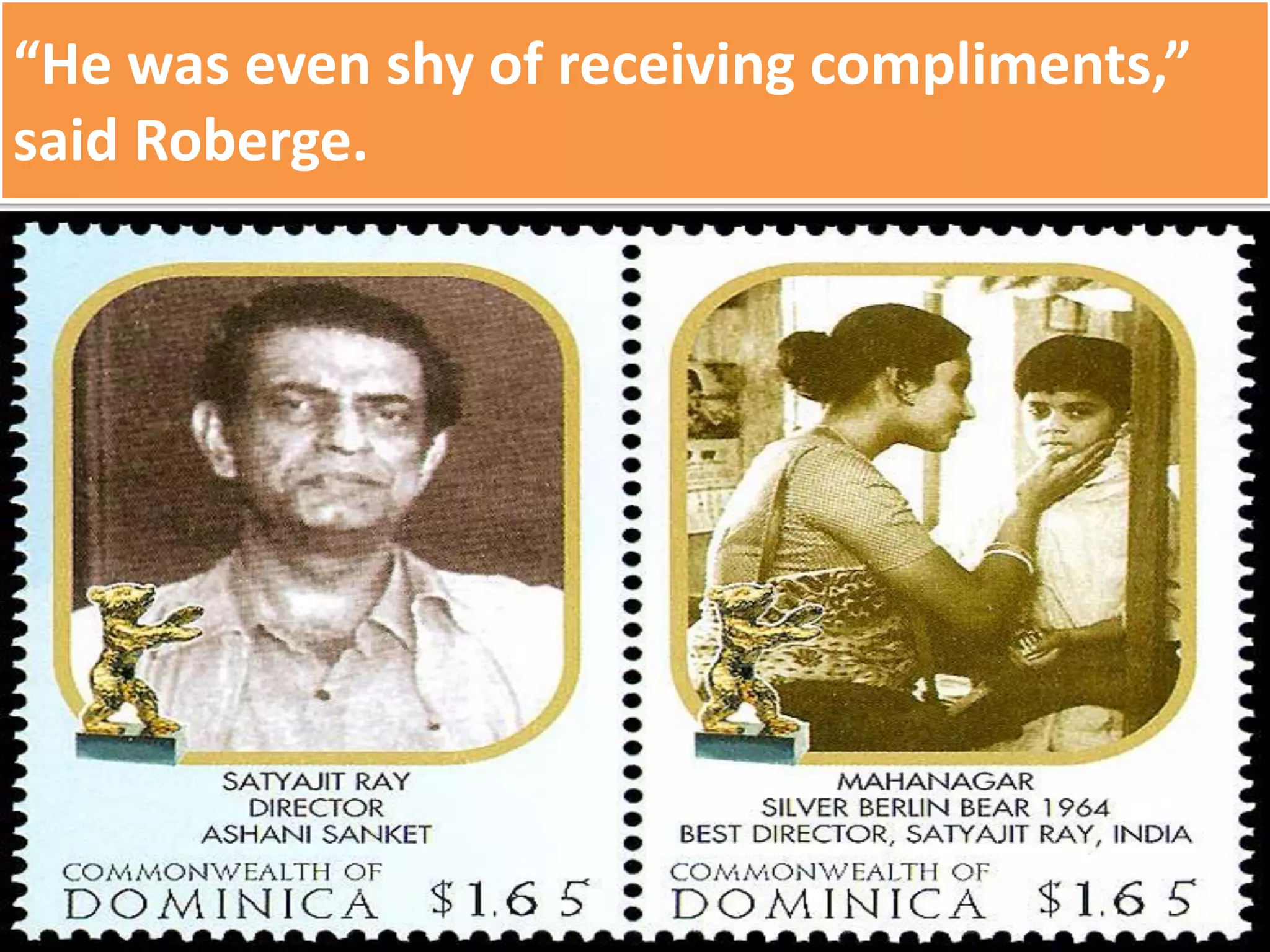

![Manikda [as Ray was affectionately called by his

friends] was a shy person and always very discreet

about displaying his emotions,” said Roberge.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rendezvouswithray-140530105457-phpapp01/75/Rendezvous-with-ray-20-2048.jpg)

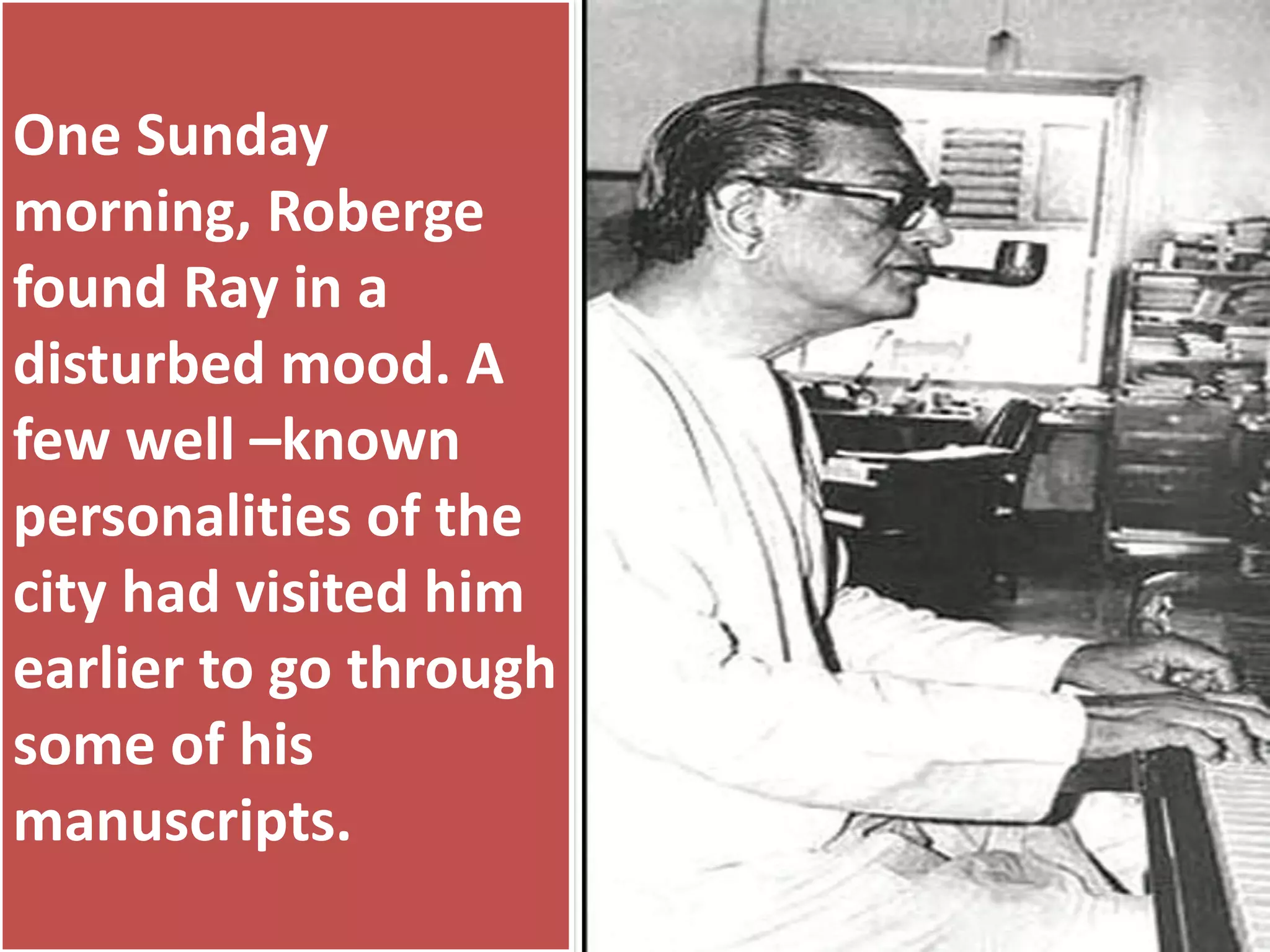

![“He had grown

so weak that he

looked frail as a

child. I did not

stay long, and as

I was leaving,

Manikda said,

‘Bhalo laglo’ [it

was nice]. Those

were his last

words to me,”

said Roberge.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rendezvouswithray-140530105457-phpapp01/75/Rendezvous-with-ray-41-2048.jpg)