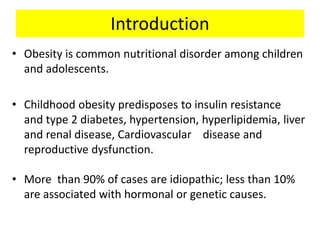

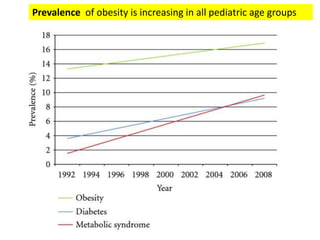

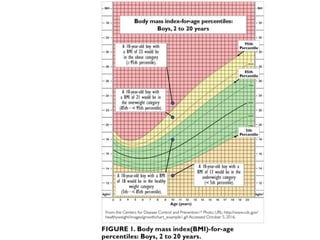

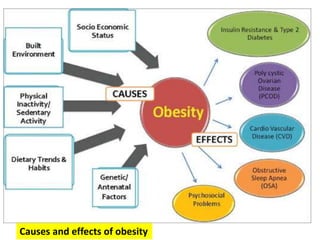

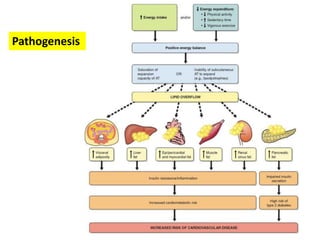

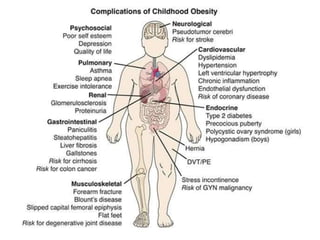

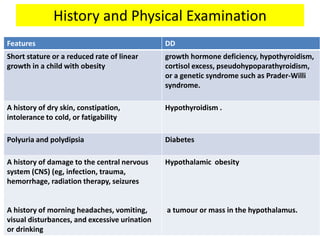

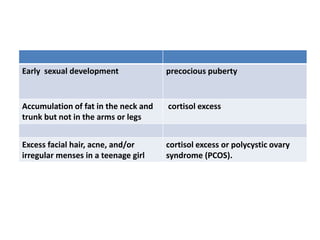

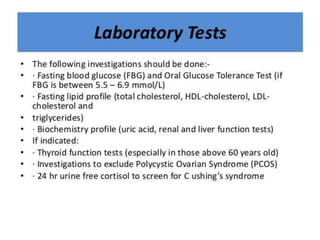

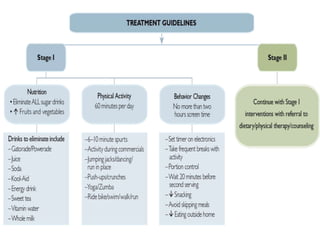

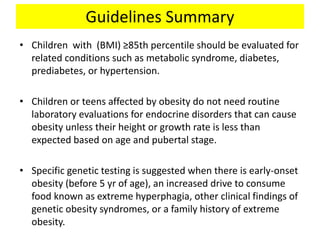

Childhood obesity is a prevalent nutritional disorder that increases the risk of various health complications, including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases. The majority of cases are idiopathic, with less than 10% linked to hormonal or genetic factors, and effective management includes lifestyle changes and, in some cases, surgical intervention. Guidelines recommend monitoring children with a BMI at or above the 85th percentile for associated conditions without routine endocrine evaluations unless growth is atypical.

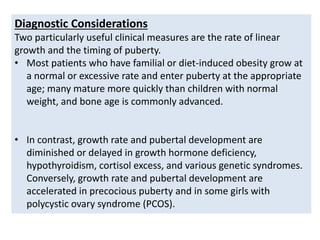

![Other tests when indicated

• Adrenal function tests, when indicated, to assess the possibility of

Cushing syndrome

• Karyotype for Prader-Willi [15q-]), as indicated by clinical history and

physical examination

• Growth hormone secretion and function tests, when indicated

• Assessment of reproductive hormones (including prolactin), when

indicated

• Serum calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid hormone levels to

evaluate for suspected pseudohypoparathyroidism

• Serum leptin

• When clinically indicated, obtain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

of the brain with focus on the hypothalamus and pituitary.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pediatricobesity-200807210504/85/Pediatric-obesity-23-320.jpg)

![References

• D'Adamo E, Cali AM, Weiss R, Santoro N, Pierpont B, Northrup V. Central role of fatty liver in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance in

obese adolescents. Diabetes Care. 2010 Aug. 33(8):1817-22. [Medline].

• Ruiz-Extremera A, Carazo A, Salmerón A, et al. Factors associated with hepatic steatosis in obese children and adolescents. J Pediatr

Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011 Aug. 53(2):196-201. [Medline].

• Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents,

1999-2010. JAMA. 2012 Feb 1. 307(5):483-90. [Medline].

• Eneli I, Dele Davis H. Epidemiology of childhood obesity. Dele Davis H, ed. Obesity in Childhood & Adolescence. Westport, Conn: Praeger

Perspectives; 2008. Vol 1.: 3-19.

• Ortega FB, Labayen I, Ruiz JR, et al. Improvements in fitness reduce the risk of becoming overweight across puberty. Med Sci Sports

Exerc. 2011 Oct. 43(10):1891-7. [Medline].

• Rosen CL. Clinical features of obstructive sleep apnea hypoventilation syndrome in otherwise healthy children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999

Jun. 27(6):403-9. [Medline].

• Juonala M, Magnussen CG, Berenson GS, et al. Childhood adiposity, adult adiposity, and cardiovascular risk factors. N Engl J Med. 2011

Nov 17. 365(20):1876-85. [Medline].

• Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Story M, Standish AR. Dieting and unhealthy weight control behaviors during adolescence: associations

with 10-year changes in body mass index. J Adolesc Health. 2012 Jan. 50(1):80-6. [Medline]. [Full Text].

• Parker ED, Sinaiko AR, Kharbanda EO, Margolis KL, Daley MF, Trower NK, et al. Change in Weight Status and Development of

Hypertension. Pediatrics. 2016 Mar. 137 (3):1-9. [Medline].

• Brown T. Obesity, High BMI Raise Hypertension Risk in Kids, Teenagers. Medscape Medical News. Available

at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/859416. February 25, 2016; Accessed: March 30, 2016.

• Perry DC, Metcalfe D, Lane S, Turner S. Childhood Obesity and Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis. Pediatrics. 2018 Nov. 142

(5):[Medline].

• Di Sario A, Candelaresi C, Omenetti A, Benedetti A. Vitamin E in chronic liver diseases and liver fibrosis. Vitam Horm. 2007. 76:551-

73. [Medline].

• Akin L, Kurtoglu S, Yikilmaz A, Kendirci M, Elmali F, Mazicioglu M. Fatty liver is a good indicator of subclinical atherosclerosis risk in

obese children and adolescents regardless of liver enzyme elevation. Acta Paediatr. 2012 Nov 28. [Medline].

• Inge TH, King WC, Jenkins TM, et al. The effect of obesity in adolescence on adult health status. Pediatrics. 2013 Dec. 132(6):1098-

104. [Medline].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pediatricobesity-200807210504/85/Pediatric-obesity-32-320.jpg)

![• Ogden CL, Yanovski SZ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterology. May 2007.

132:2087-2102. [Medline]. [Full Text].

• Fiore H, Travis S, Whalen A, Auinger P, Ryan S. Potentially protective factors associated with healthful body

mass index in adolescents with obese and nonobese parents: a secondary data analysis of the third national

health and nutrition examination survey, 1988-1994. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006 Jan. 106(1):55-64; quiz 76-

9. [Medline].

• Flegal KM, Ogden CL, Wei R, et al. Prevalence of overweight in US children: comparison of US growth charts

from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention with other reference values for body mass index. Am J

Clin Nutr. 2001 Jun. 73(6):1086-93. [Medline].

• McGavock JM, Torrance BD, McGuire KA, Wozny PD, Lewanczuk RZ. Cardiorespiratory fitness and the risk of

overweight in youth: the Healthy Hearts Longitudinal Study of Cardiometabolic Health. Obesity (Silver

Spring). 2009 Sep. 17(9):1802-7. [Medline].

• Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Zocca JM, Field SE, Drinkard B, Yanovski JA. Depressive symptoms and

cardiorespiratory fitness in obese adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2012 Jan. 50(1):87-92. [Medline]. [Full

Text].

• Carter PJ, Taylor BJ, Williams SM, Taylor RW. Longitudinal analysis of sleep in relation to BMI and body fat in

children: the FLAME study. BMJ. 2011 May 26. 342:d2712. [Medline]. [Full Text].

• Archbold KH, Vasquez MM, Goodwin JL, Quan SF. Effects of Sleep Patterns and Obesity on Increases in Blood

Pressure in a 5-Year Period: Report from the Tucson Children's Assessment of Sleep Apnea Study. J Pediatr.

2012 Jan 25. [Medline]. [Full Text].

• Mosli RH, Kaciroti N, Corwyn RF, Bradley RH, Lumeng JC. Effect of Sibling Birth on BMI Trajectory in the First

6 Years of Life. Pediatrics. 2016 Mar 11. [Medline].

• Garcia J. Birth of a Sibling May Decrease Obesity Ris. Medscape Medical News. Available

at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/860298. March 14, 2016; Accessed: March 30, 2016.

• Huh S, Rifas-Shiman S, Taveras E, Oken E, Gillman M. Timing of solid food introduction and risk of obesity in

preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2011 Mar. 127(3):e544-51. [Medline]. [Full Text].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pediatricobesity-200807210504/85/Pediatric-obesity-33-320.jpg)