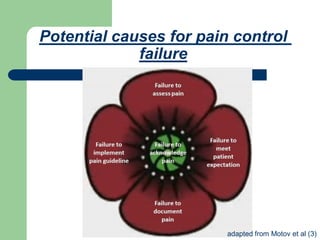

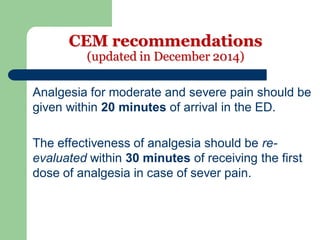

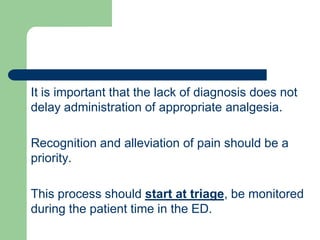

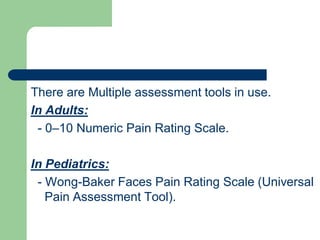

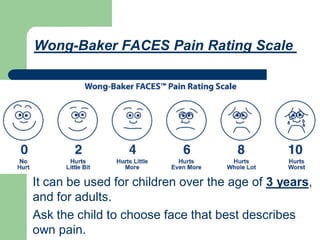

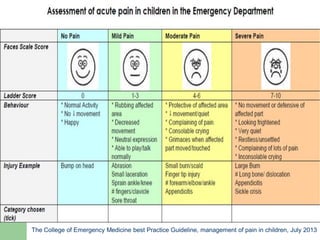

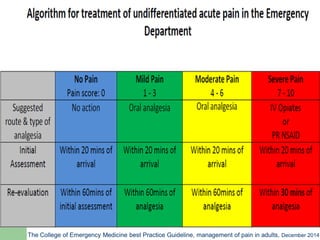

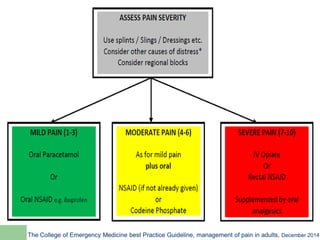

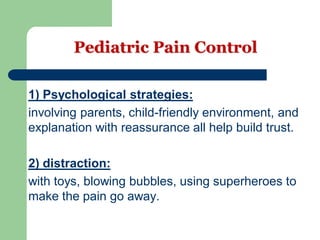

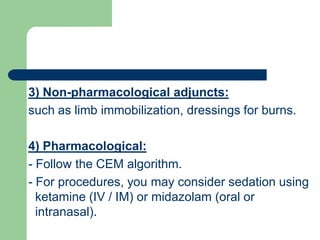

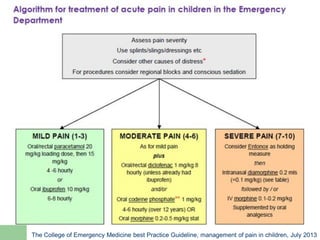

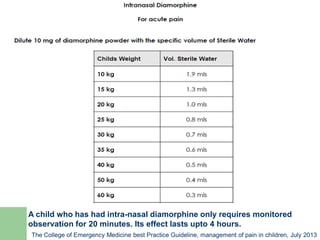

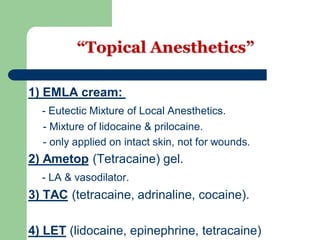

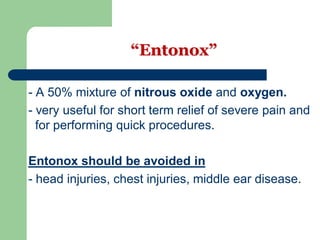

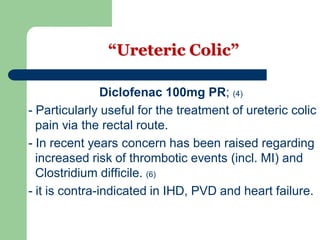

The document outlines the significance of early pain management in emergency departments (ED) and discusses various pharmacological and non-pharmacological pain control methods. It emphasizes the need for timely analgesia, regular reassessment, and appropriate documentation of pain scores. Additionally, it highlights specific considerations for managing pain in different age groups, including children and the elderly.