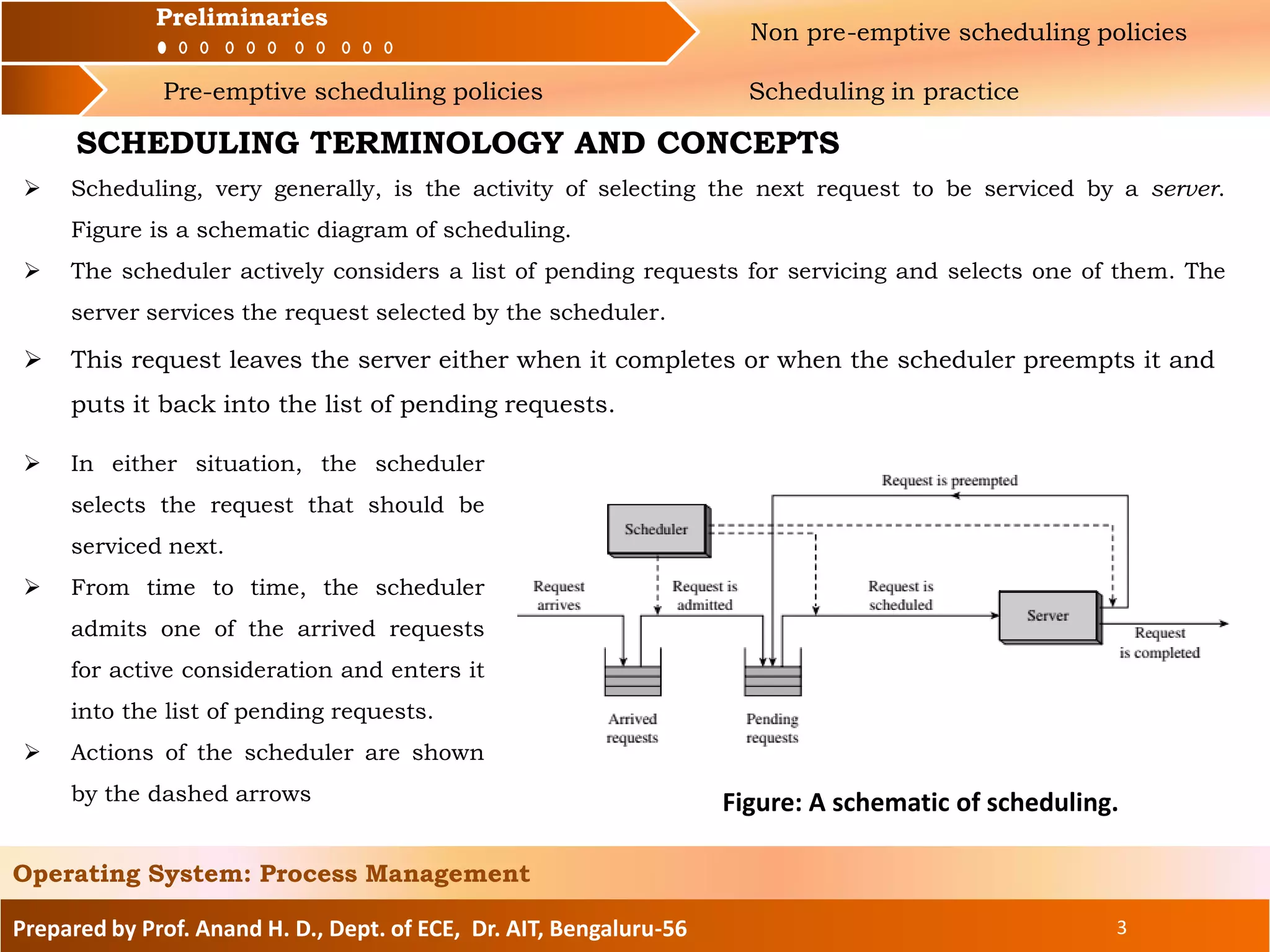

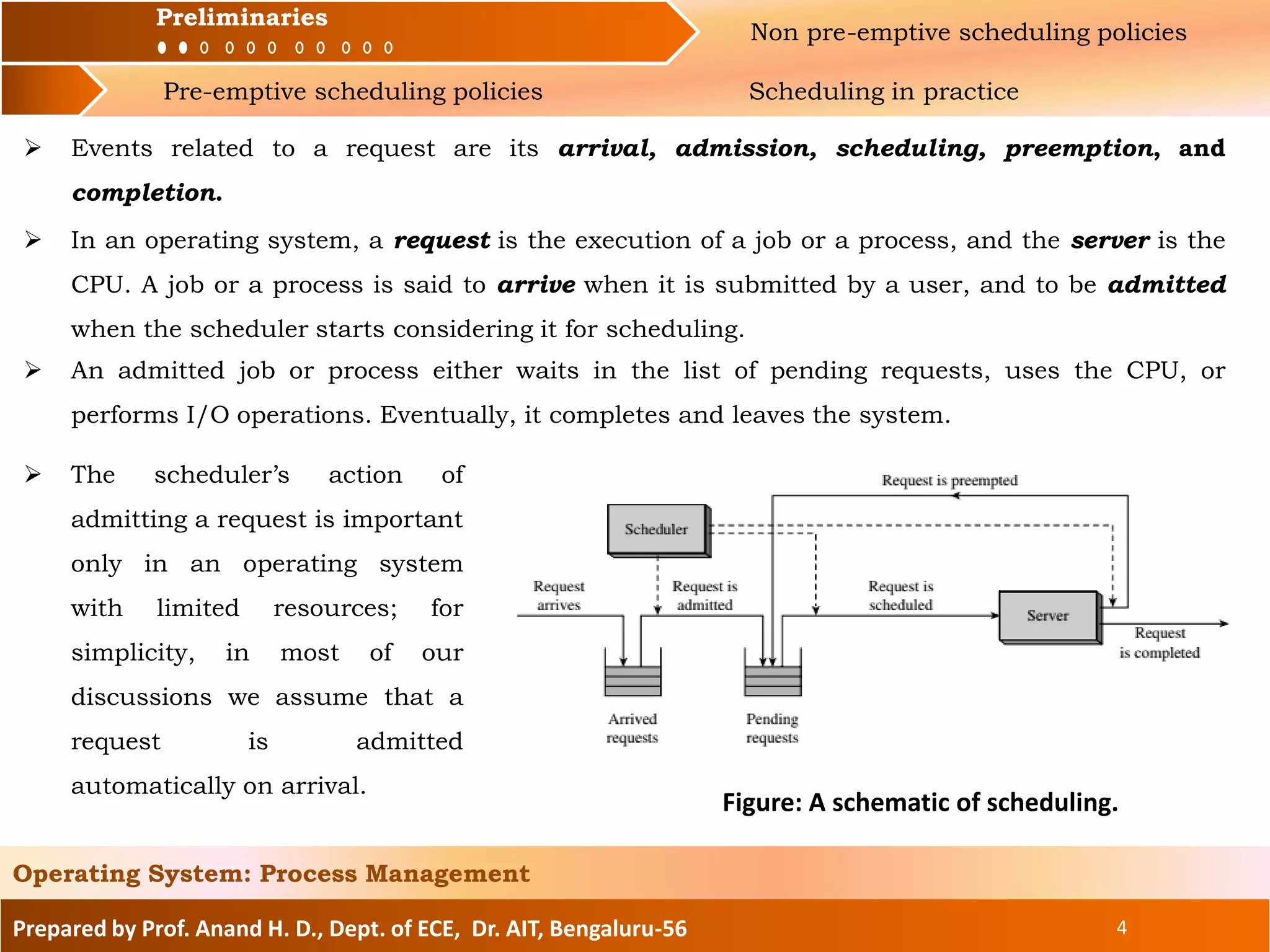

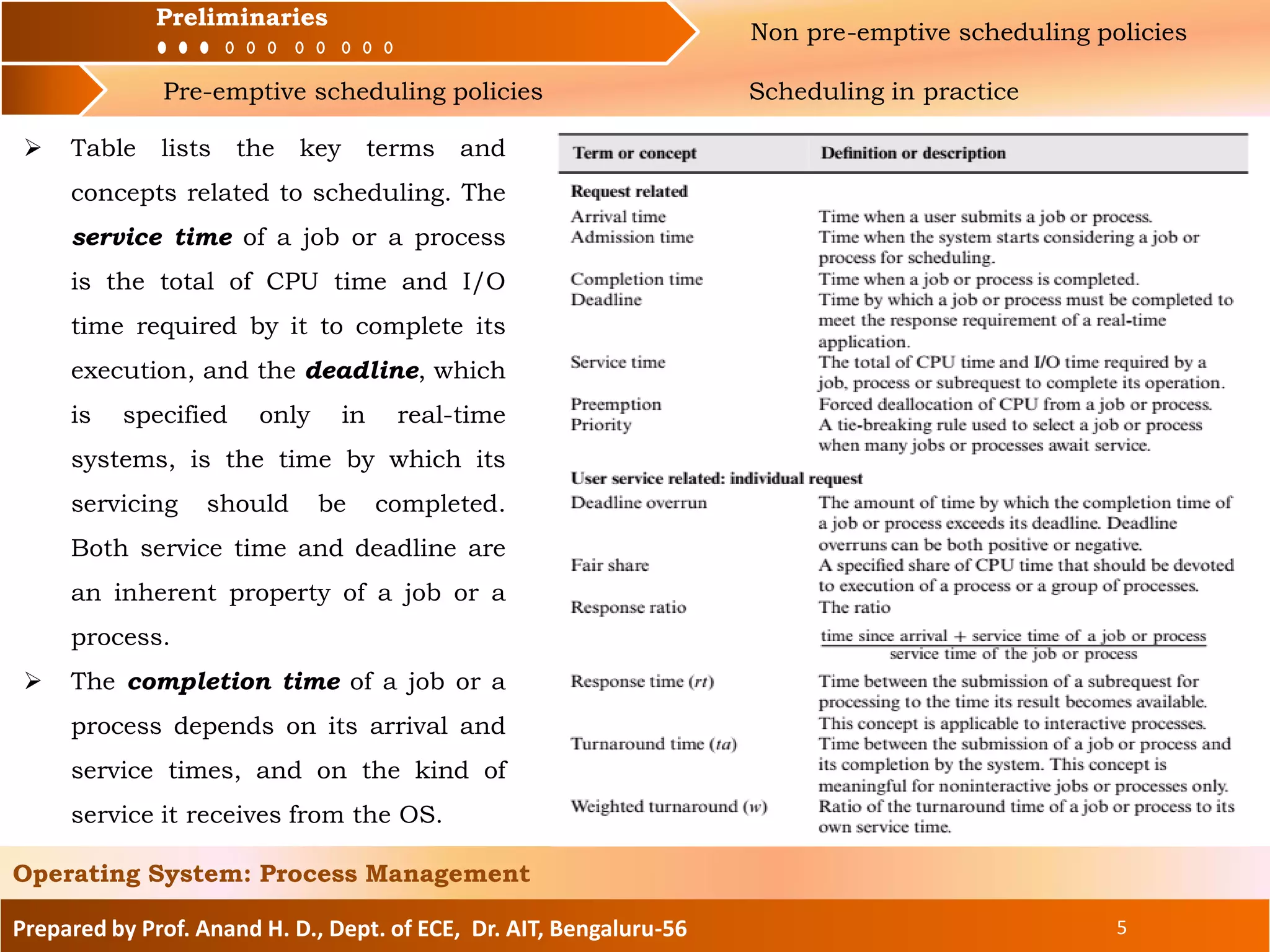

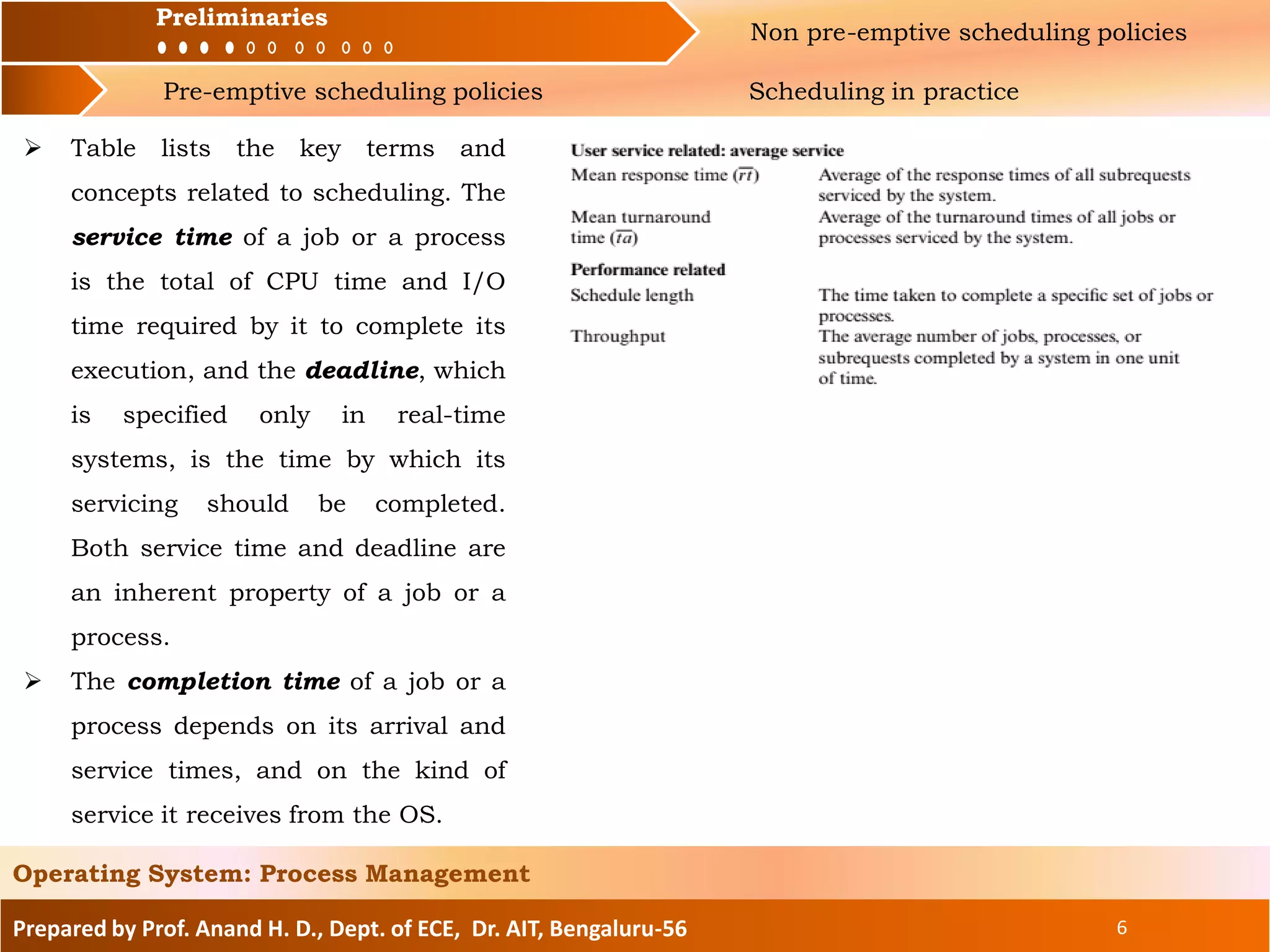

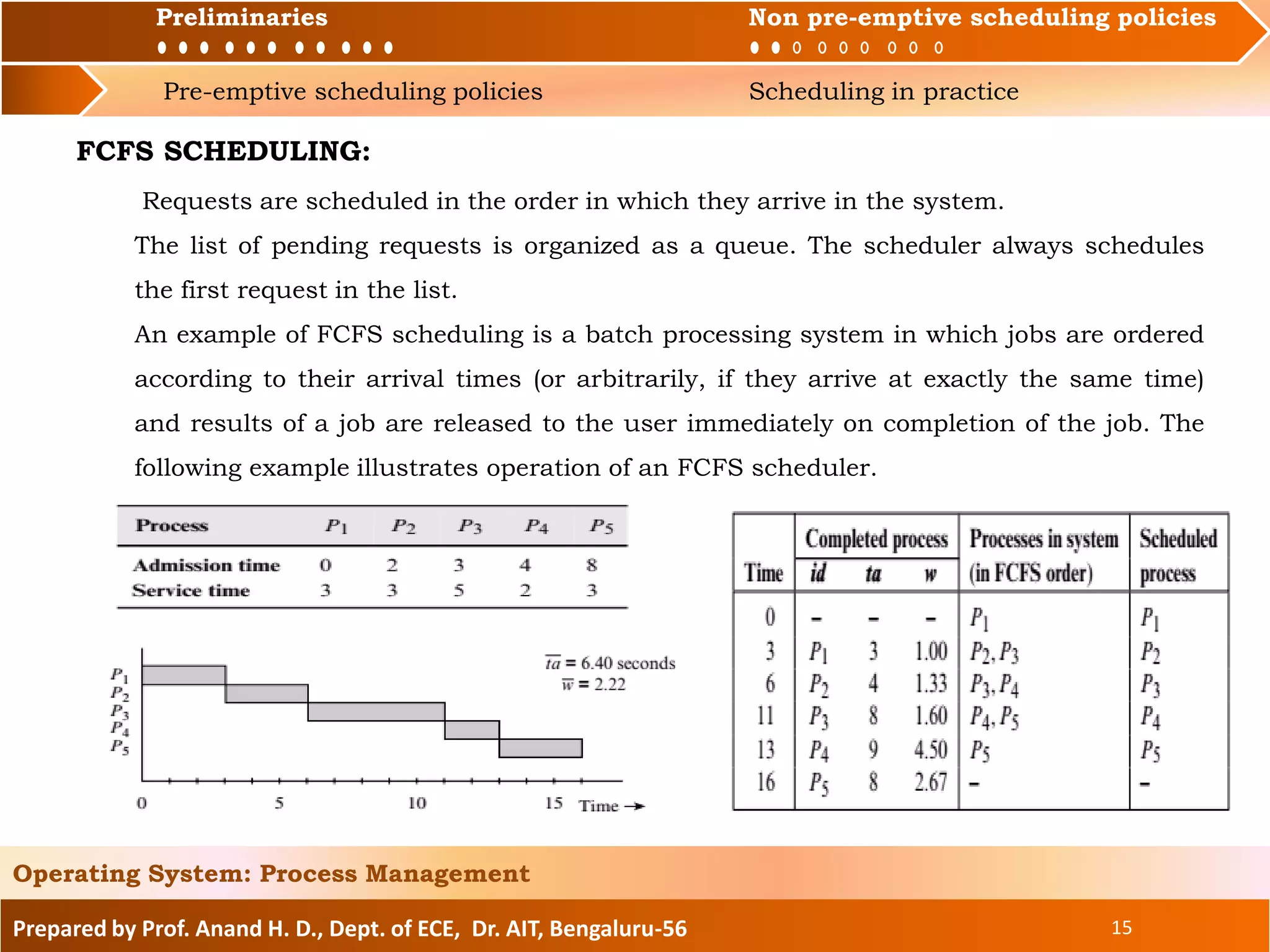

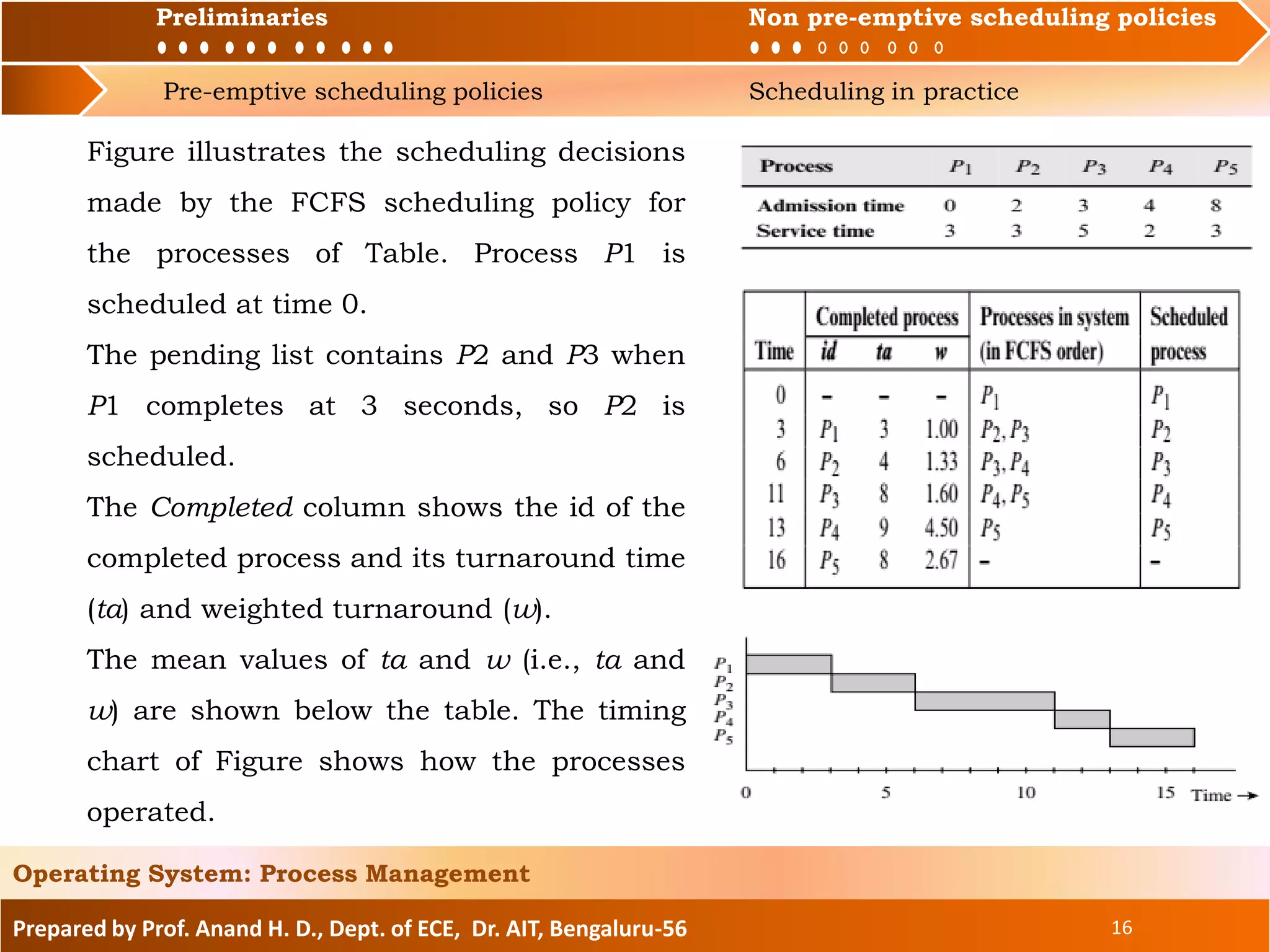

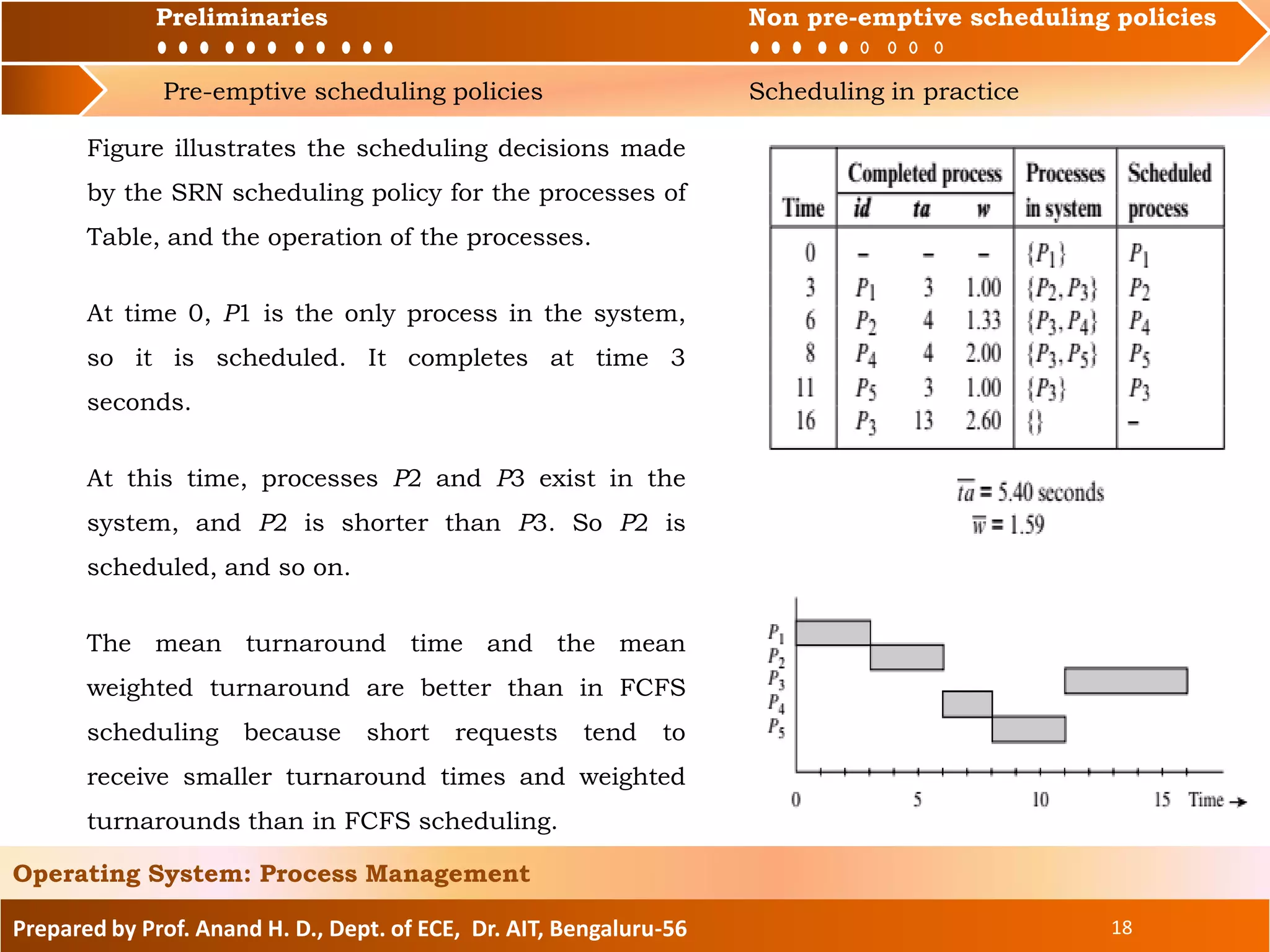

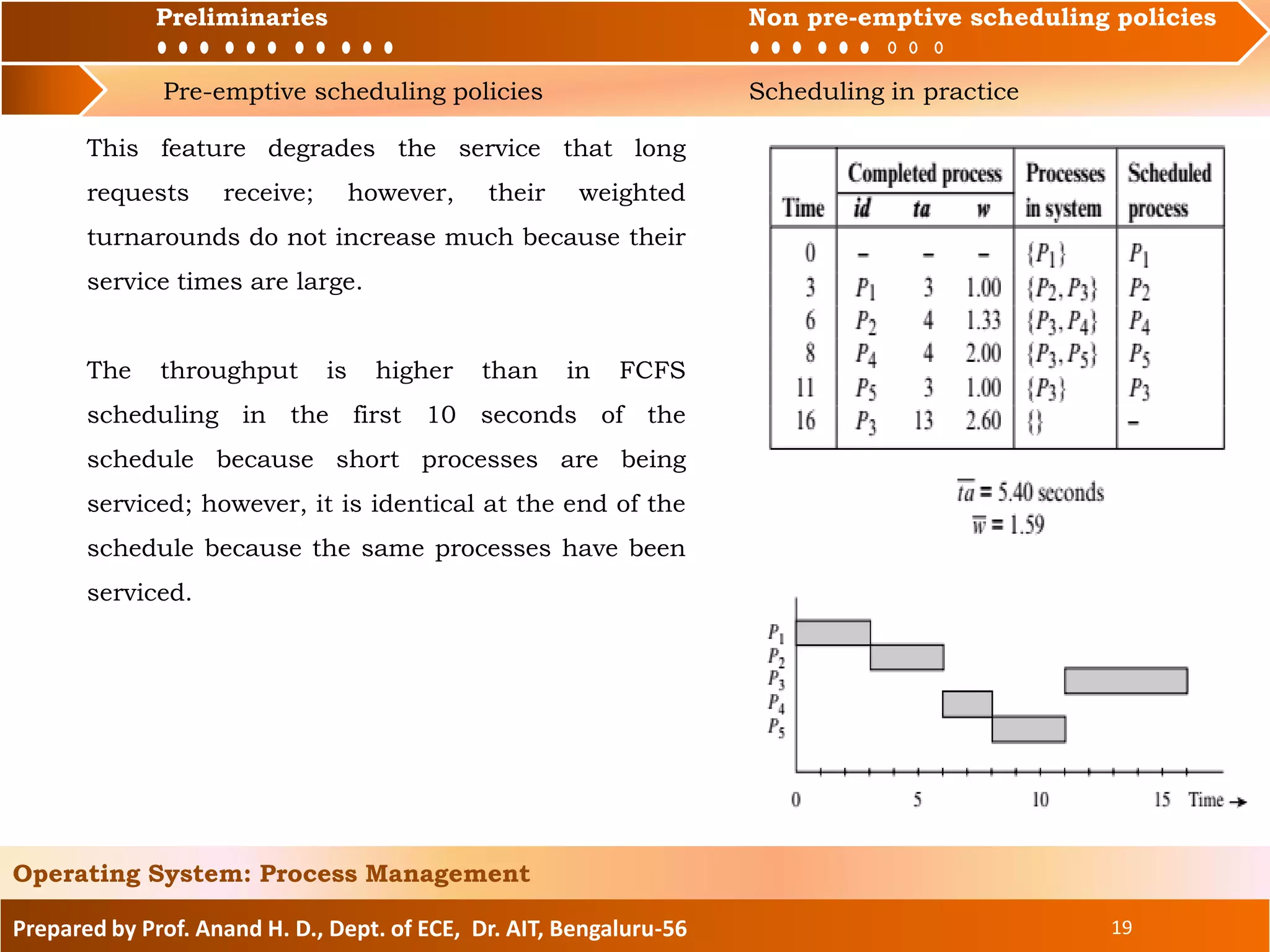

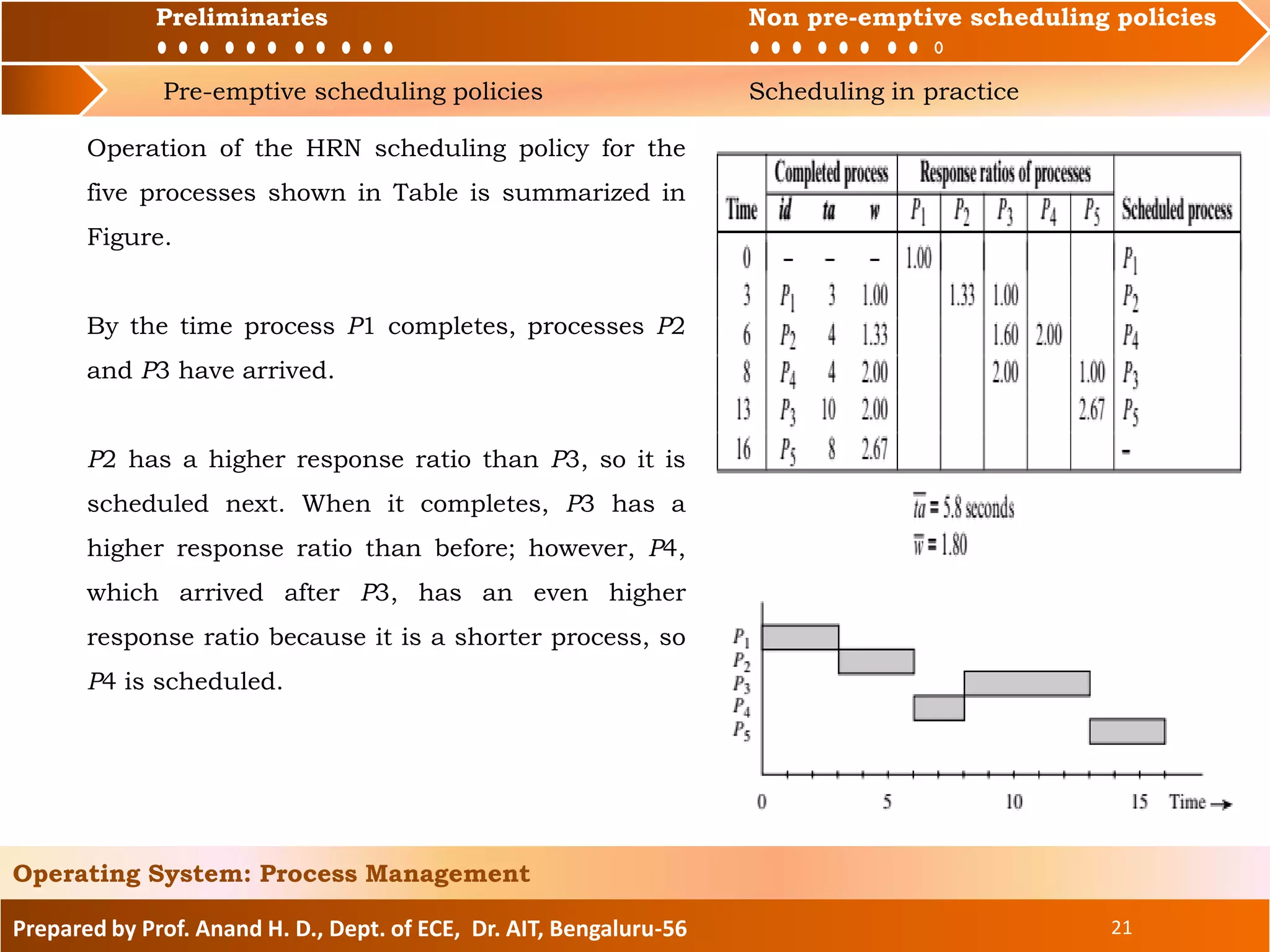

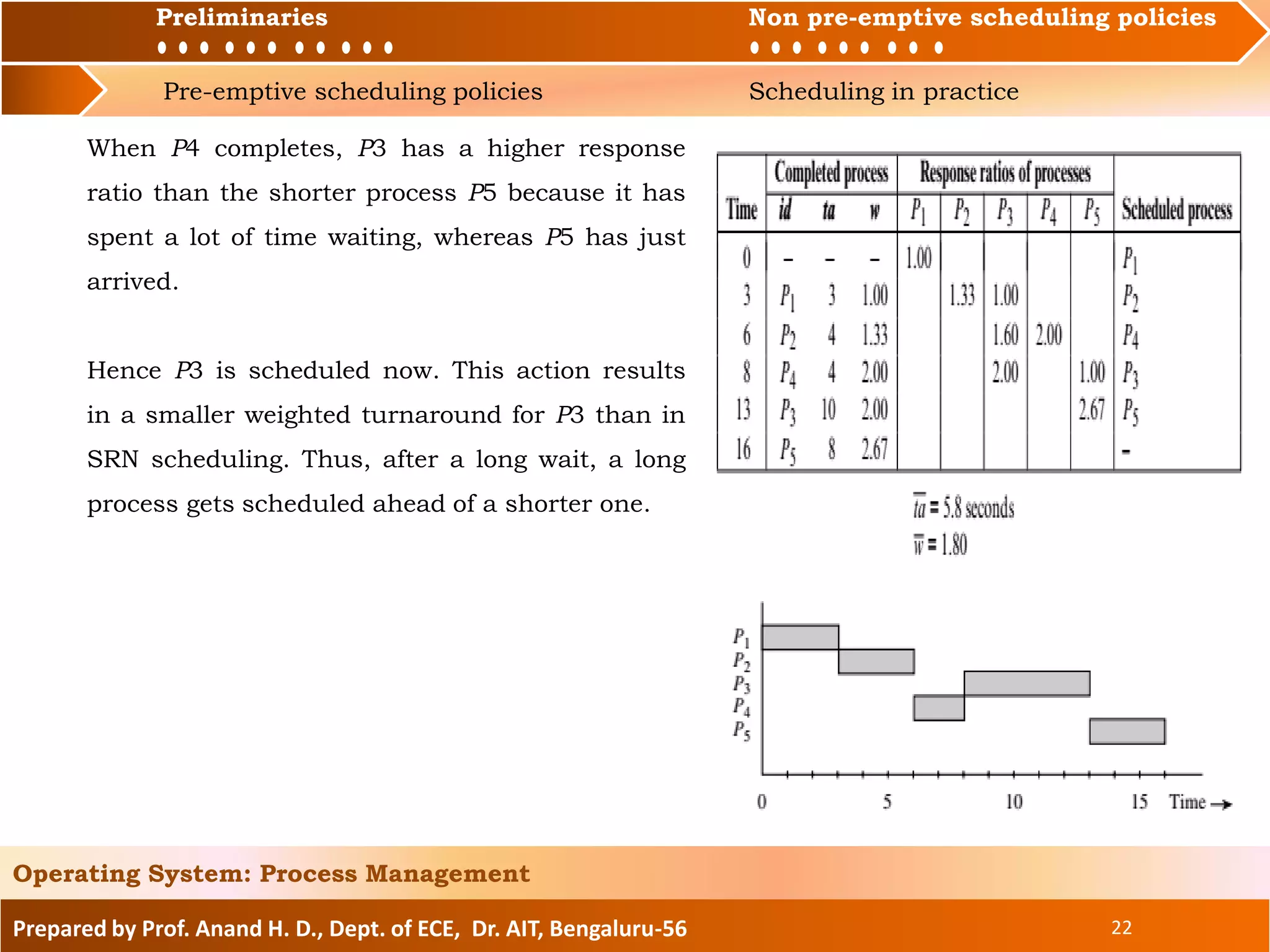

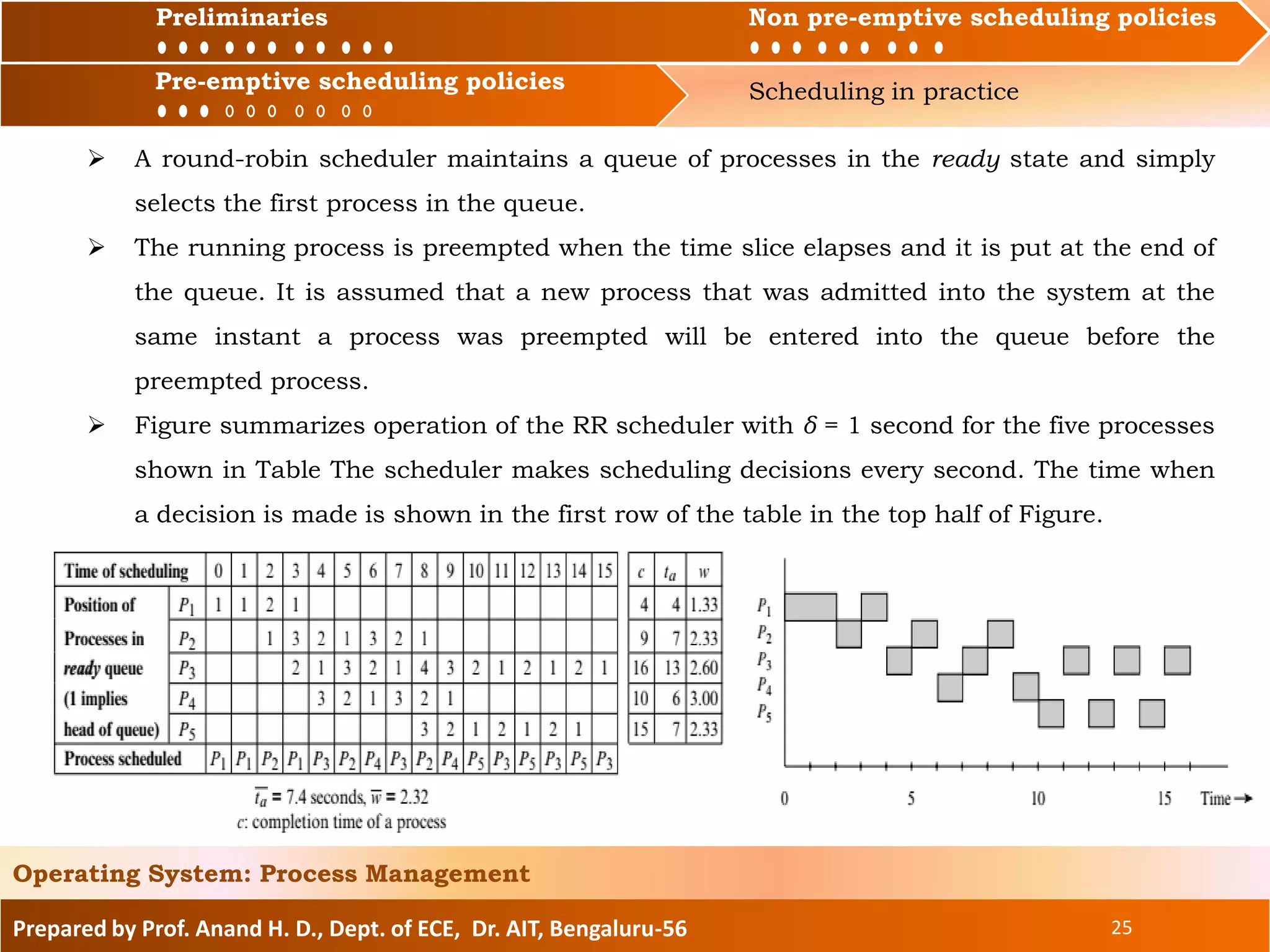

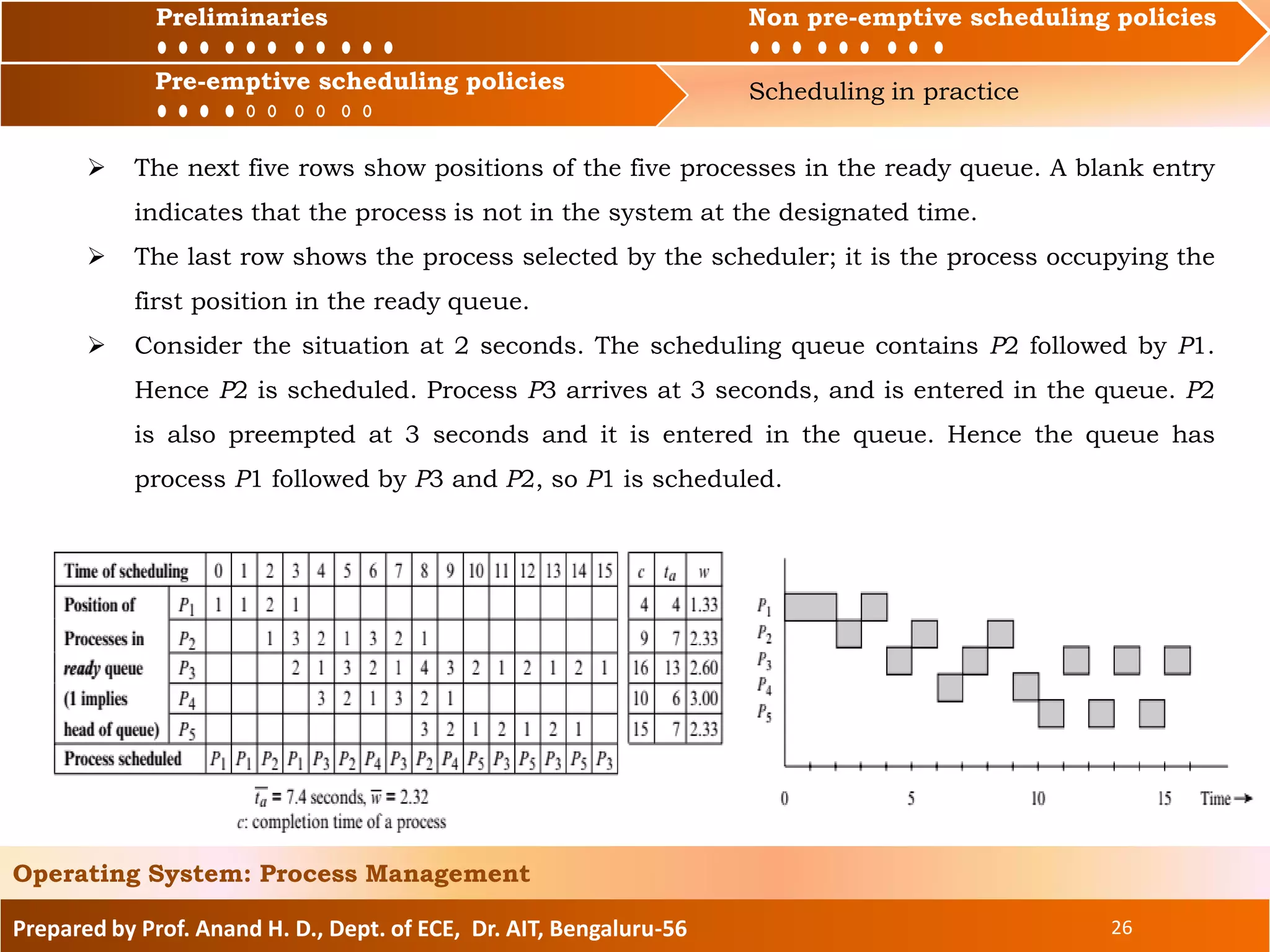

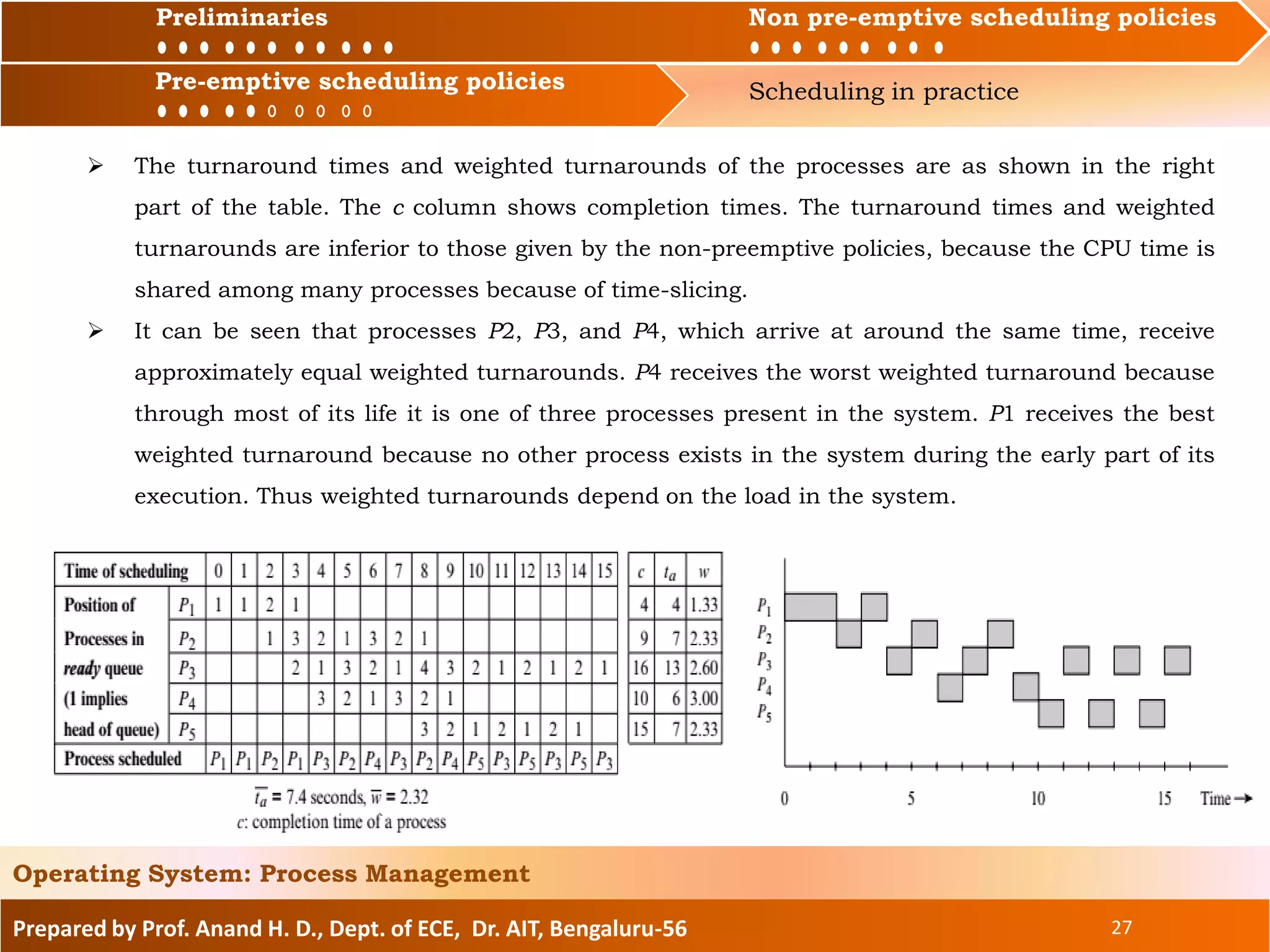

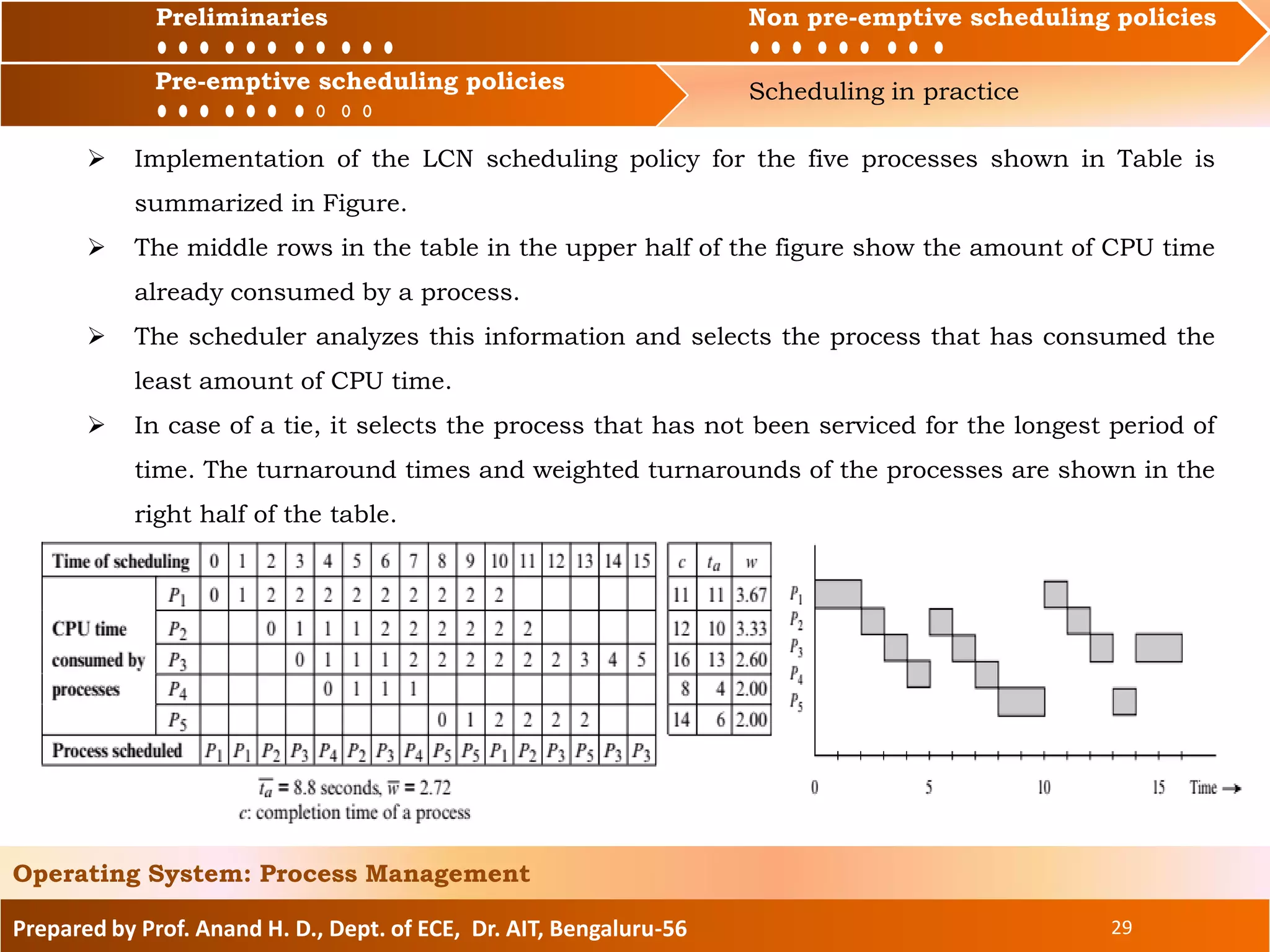

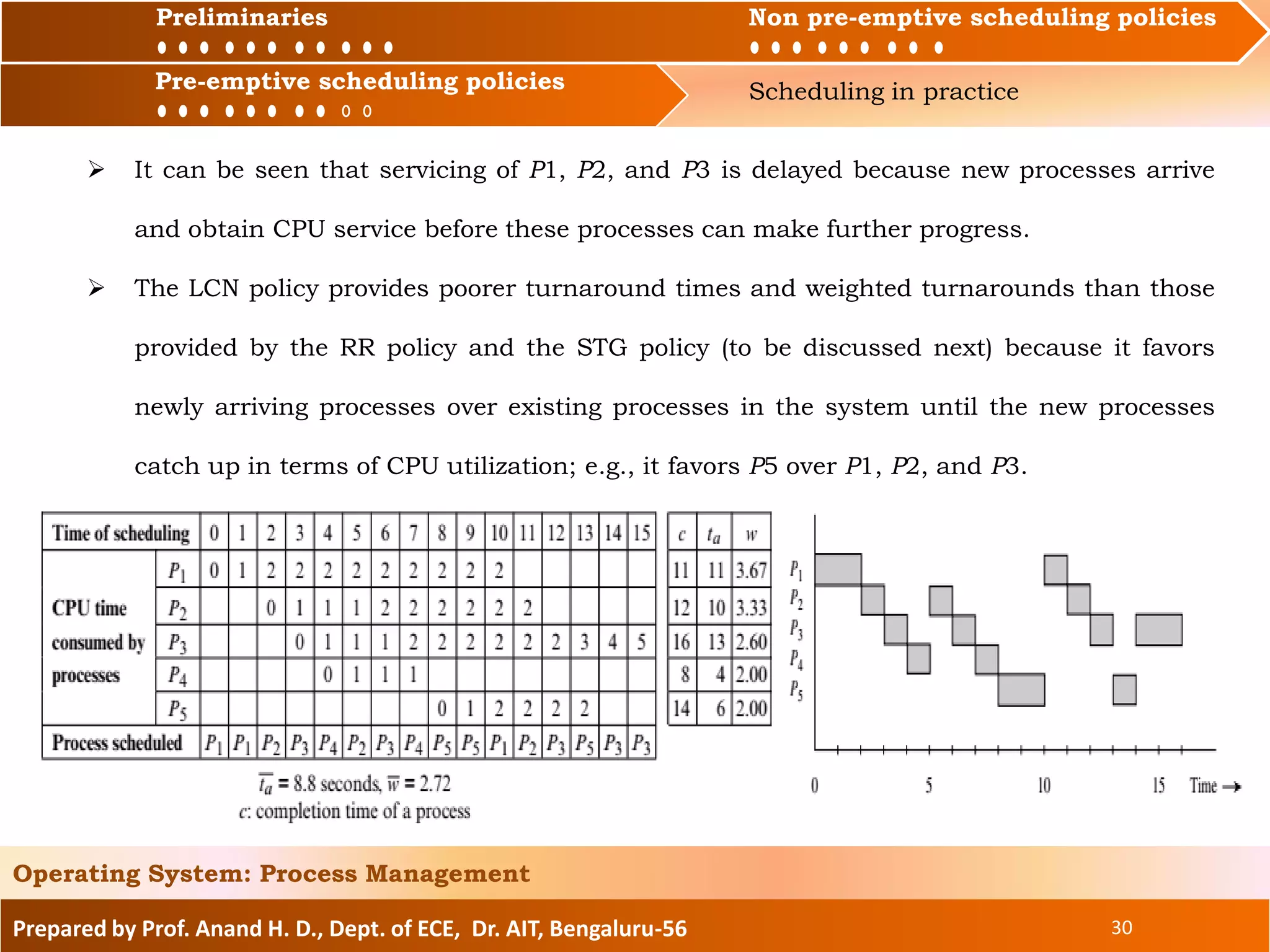

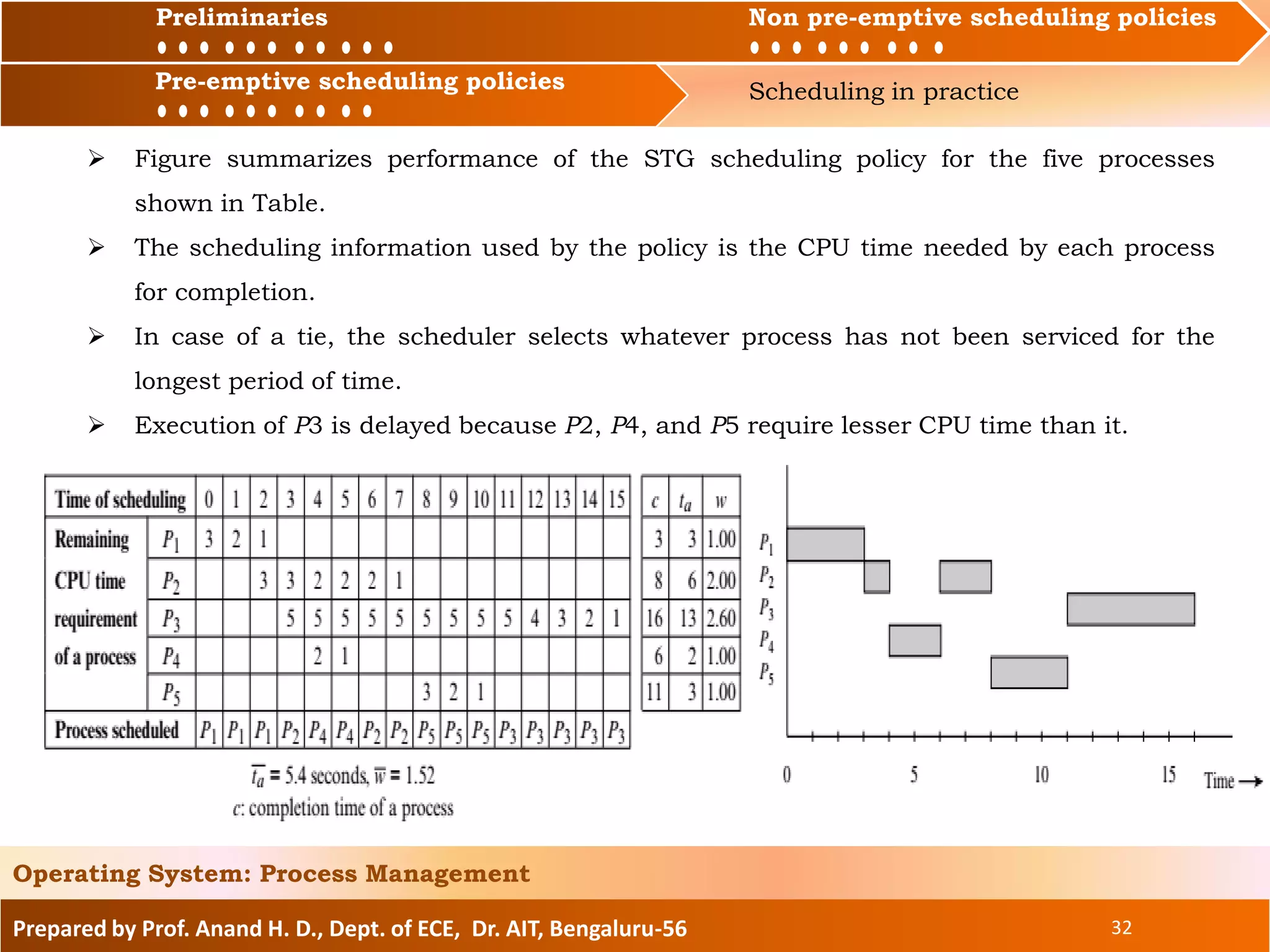

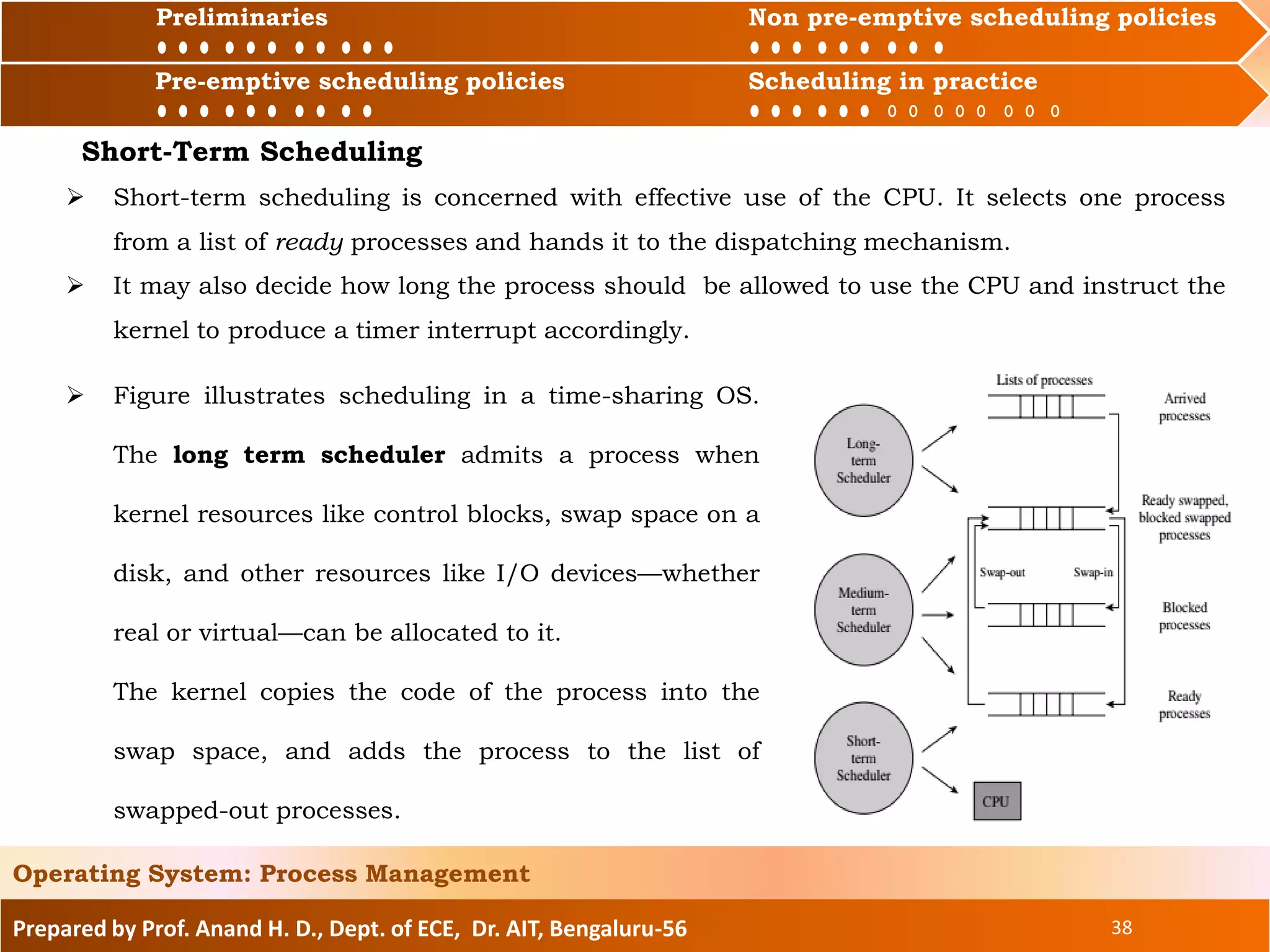

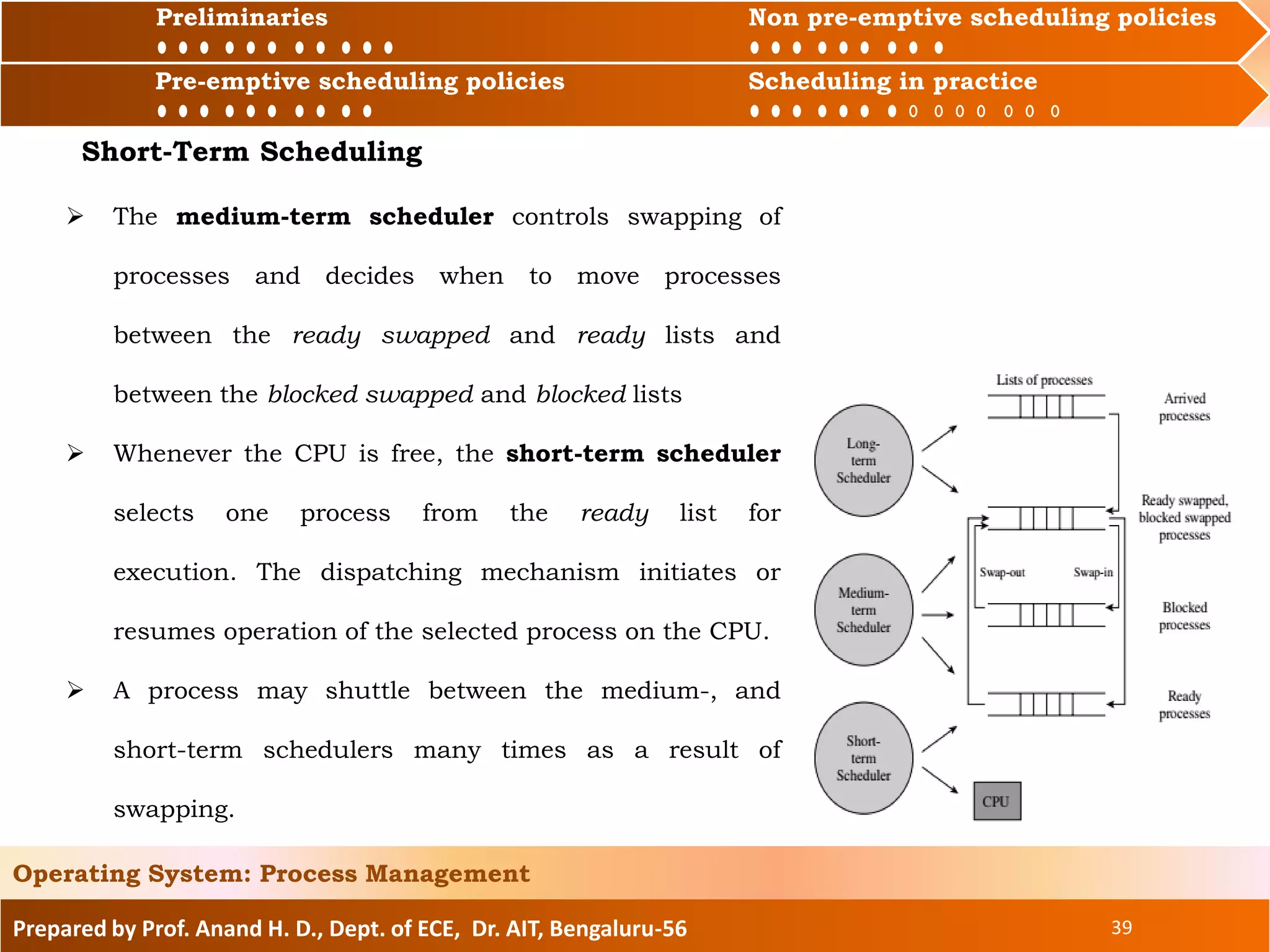

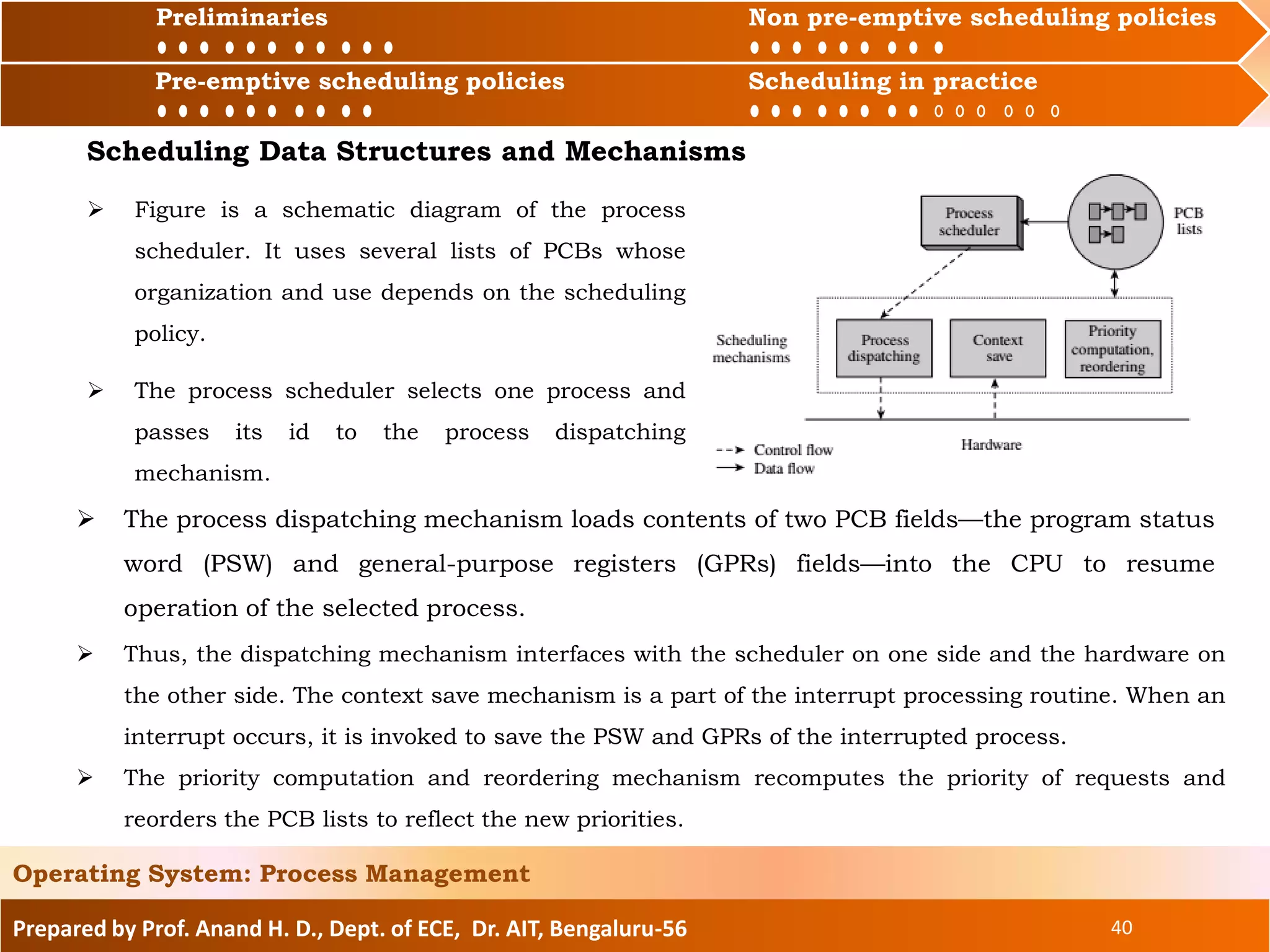

This document discusses operating system scheduling, covering both non-preemptive and preemptive scheduling policies, as well as essential concepts and metrics related to process management. It elaborates on various scheduling techniques such as First-Come, First-Served, Shortest Request Next, and Highest Response Ratio Next, analyzing their advantages and disadvantages in terms of user service and system performance. Key terms like service time, turnaround time, response time, and priority handling are introduced to demonstrate their impact on scheduling decisions.