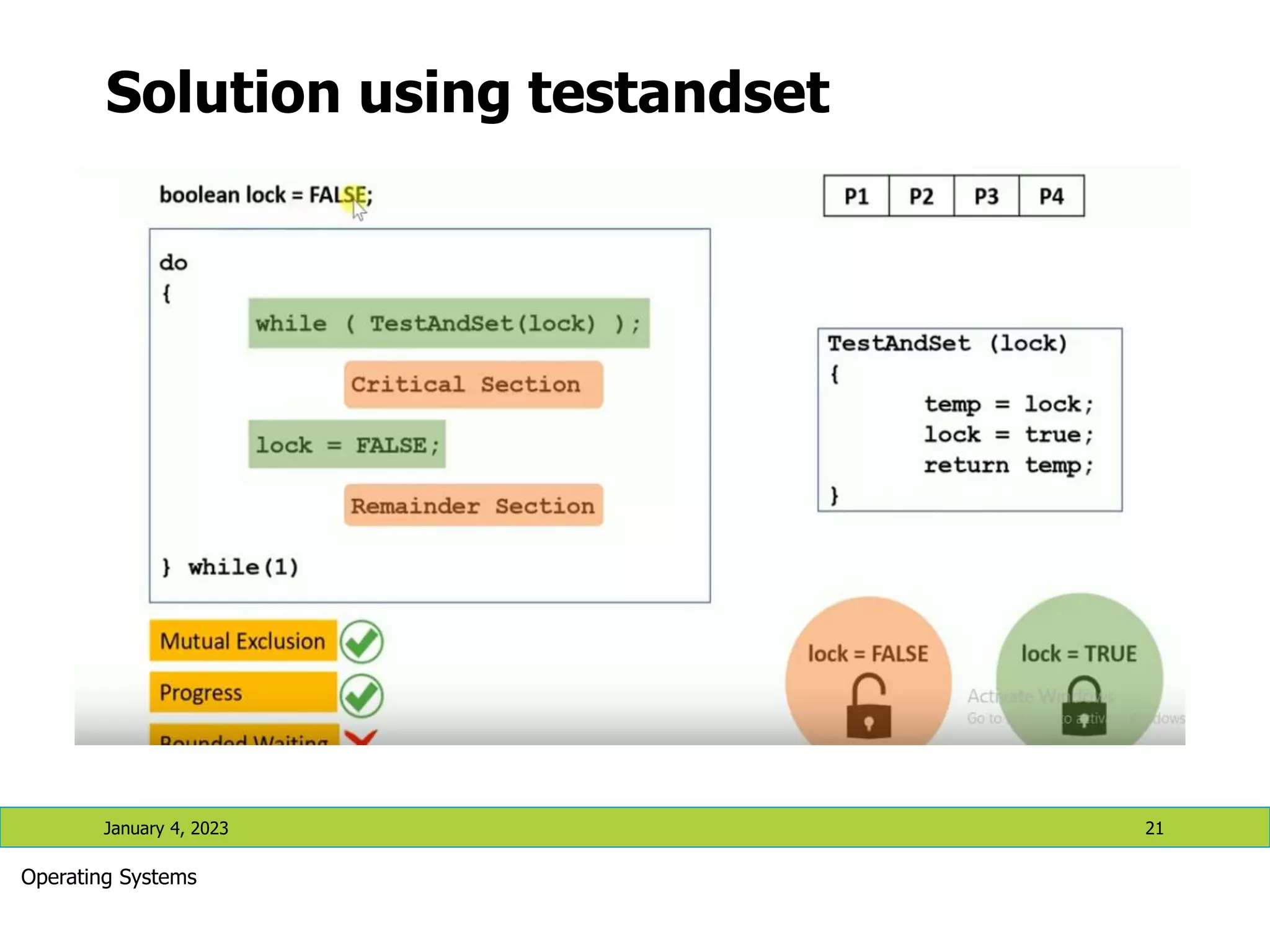

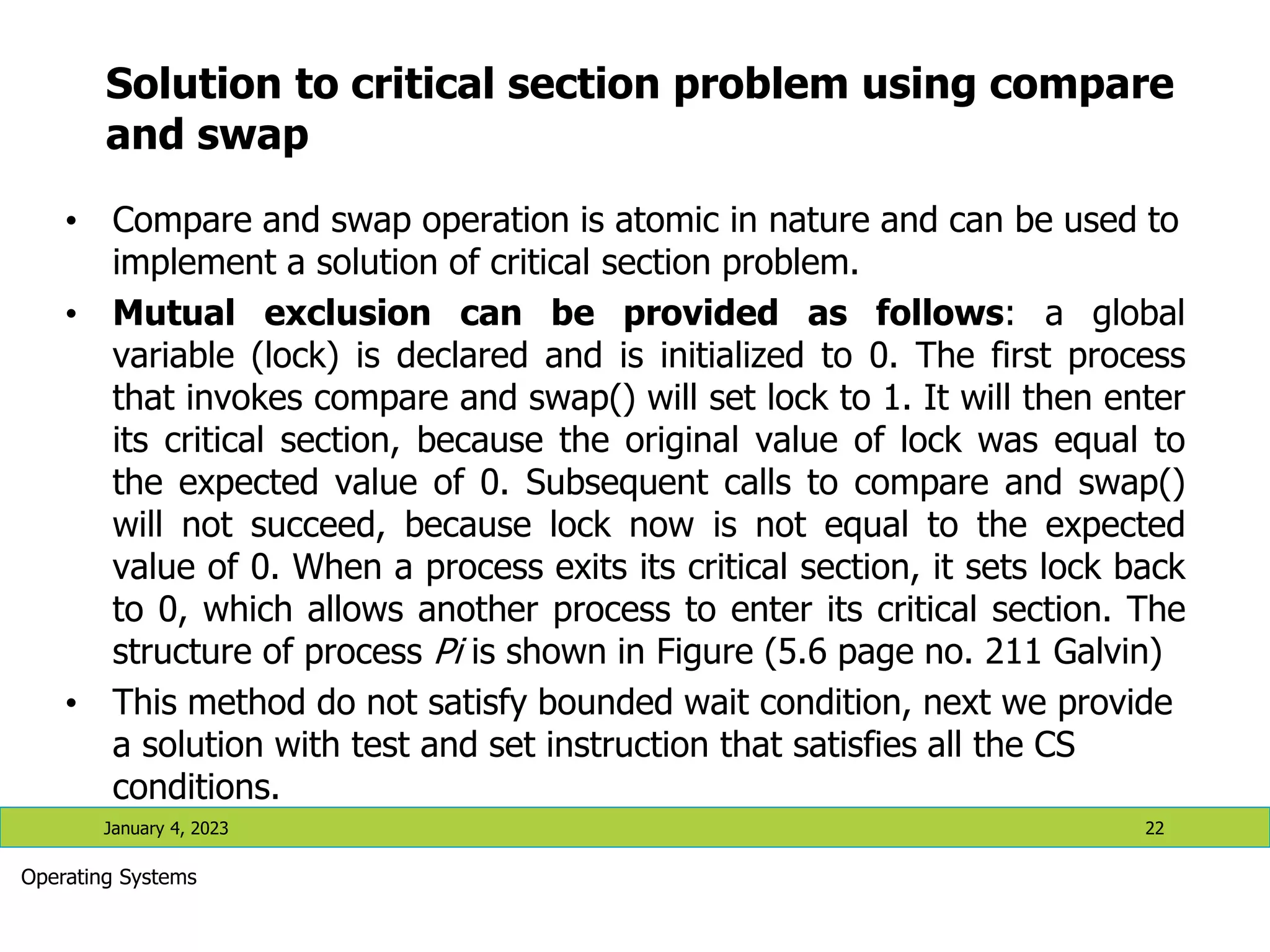

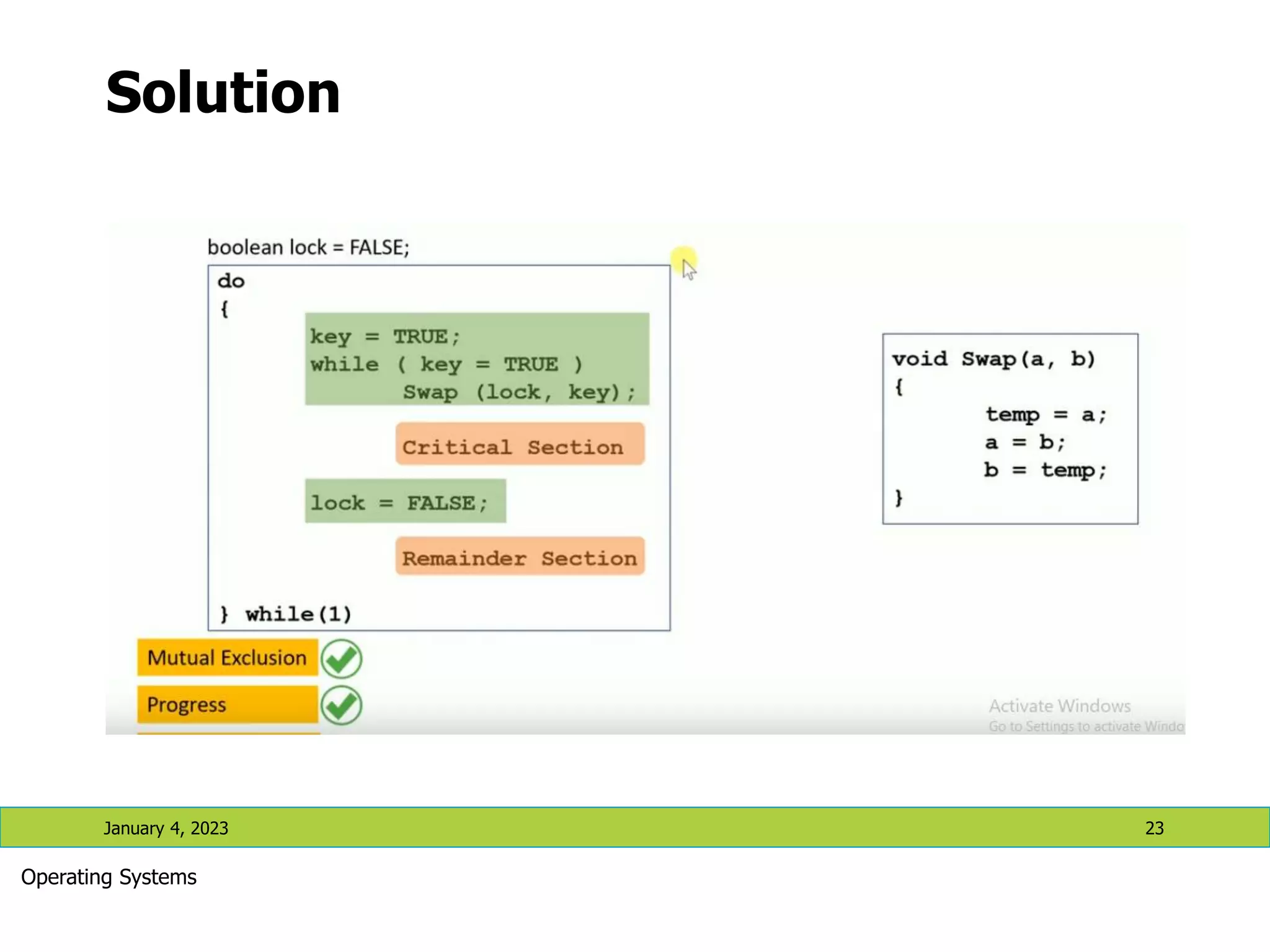

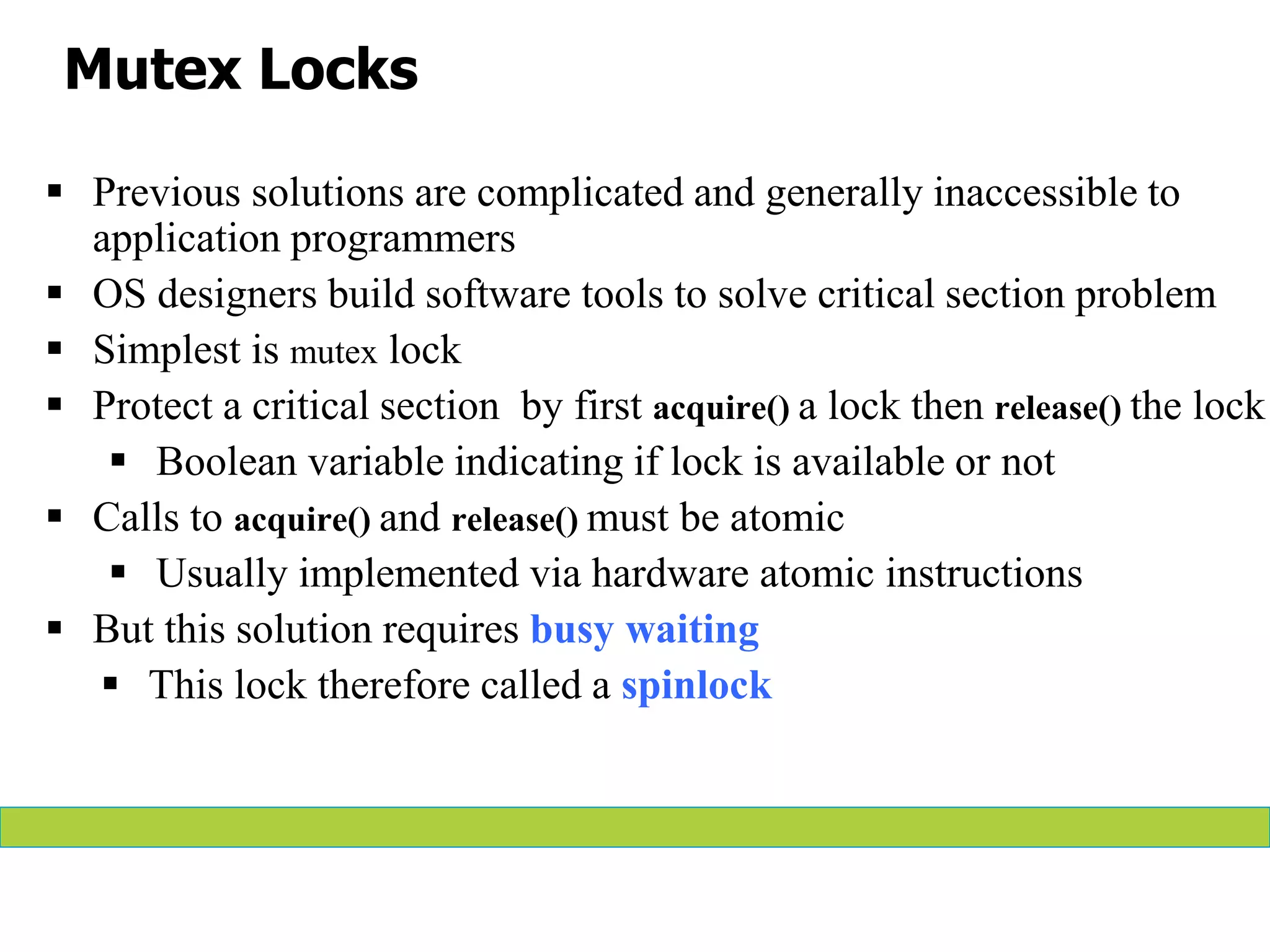

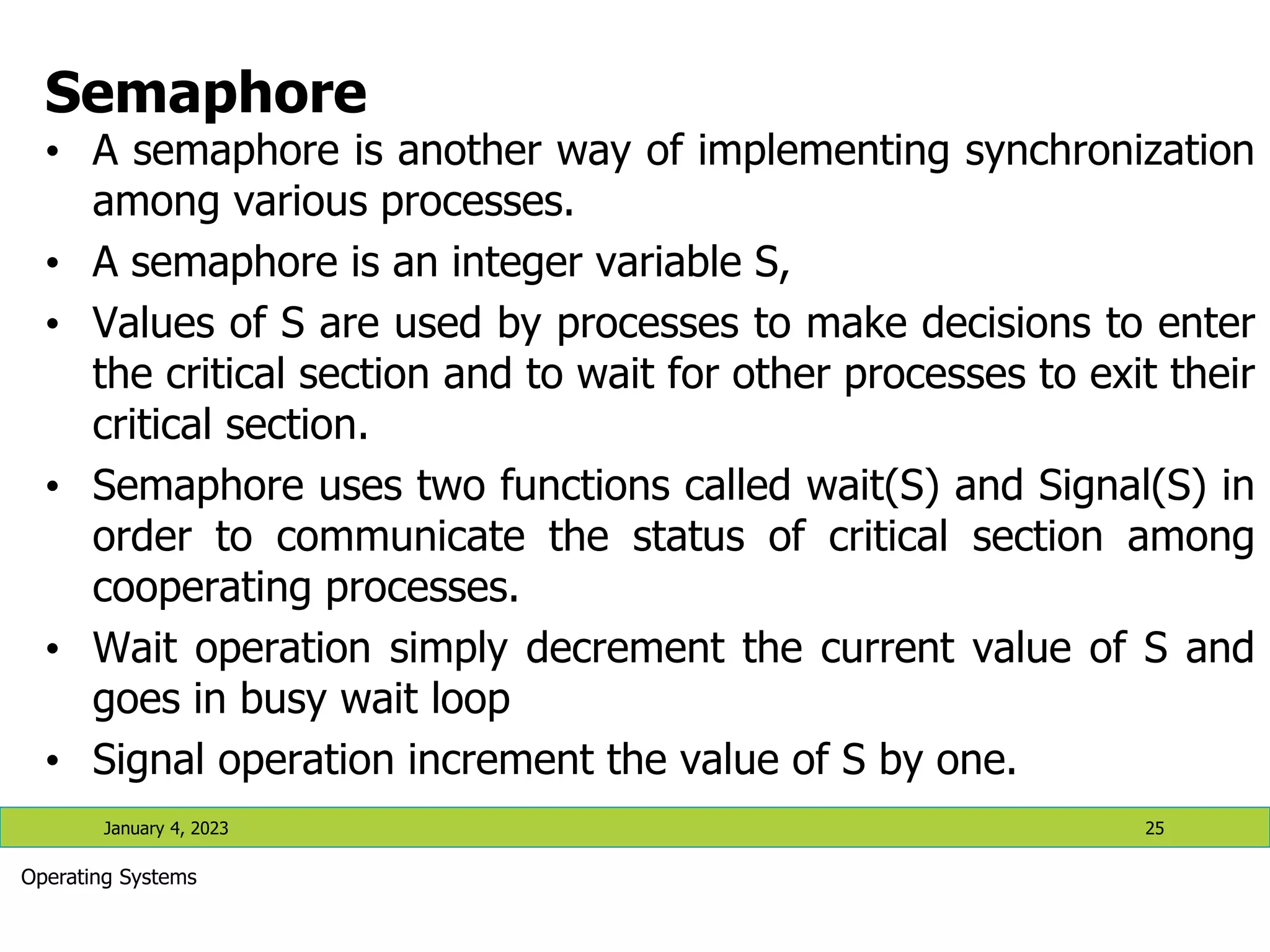

This document discusses process synchronization in operating systems. It covers the critical section problem where multiple processes need synchronized access to shared resources. Several solutions to the critical section problem are presented, including Peterson's algorithm using shared variables, and using hardware-based synchronization methods like test-and-set and compare-and-swap atomic instructions. Mutex locks are also introduced as a software-based approach where a process must acquire a lock before entering a critical section and release it after.

![Peterson’s Solution

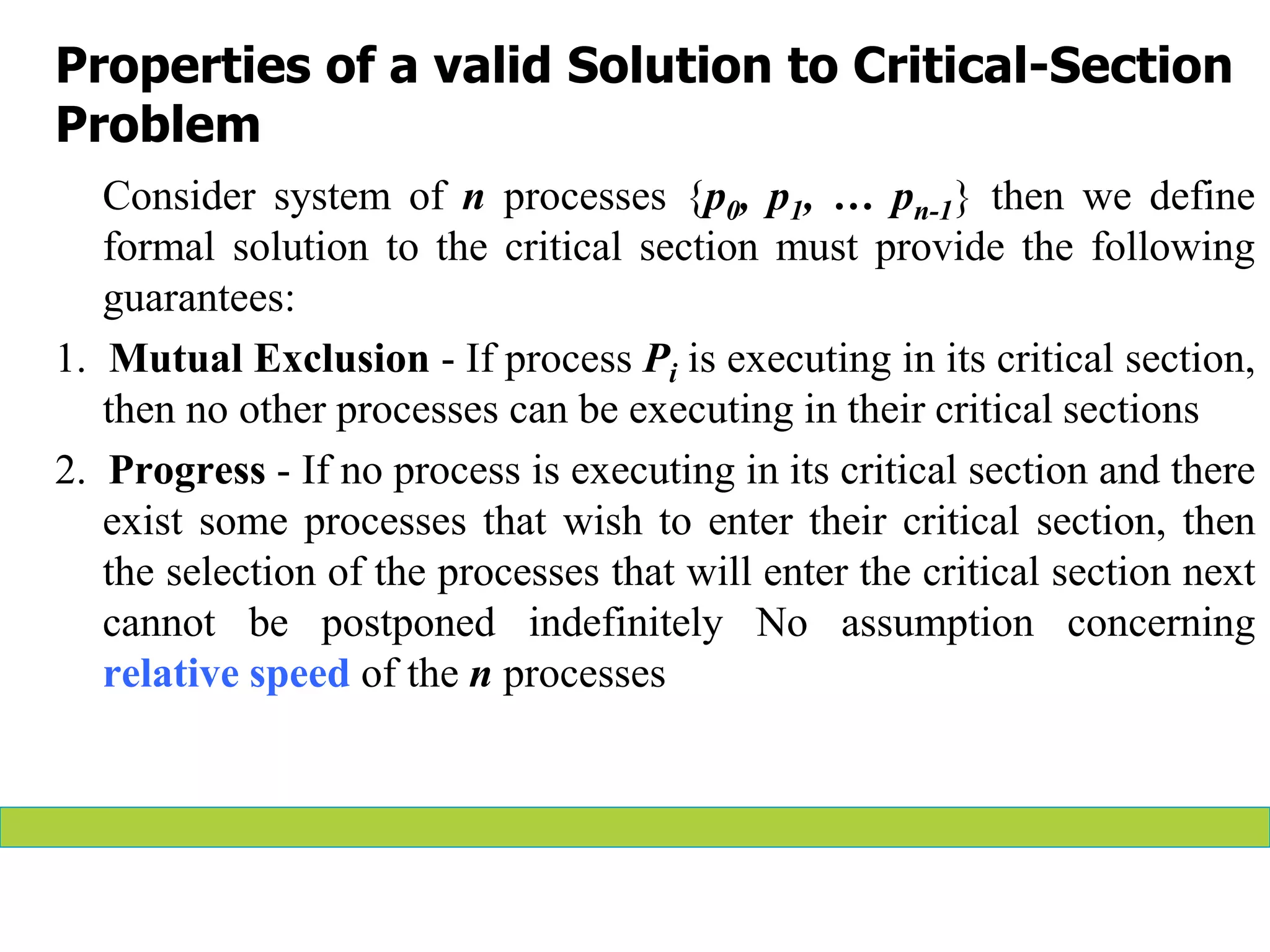

This solution provide an algorithmic description of solving the

problem of critical section, this is a two process solution.

• Assume that the load and store machine-language instructions

are atomic; that is, cannot be interrupted

• The two processes share two variables:

• int turn;

• Boolean flag[2]

• The variable turn indicates whose turn it is to enter the critical

section

• The flag array is used to indicate if a process is ready to enter

the critical section. flag[i] = true implies that process Pi is ready!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture5-processsynchronization1-230104191210-4e1c3fd4/75/Lecture-5-Process-Synchronization-1-pptx-12-2048.jpg)

![Algorithm

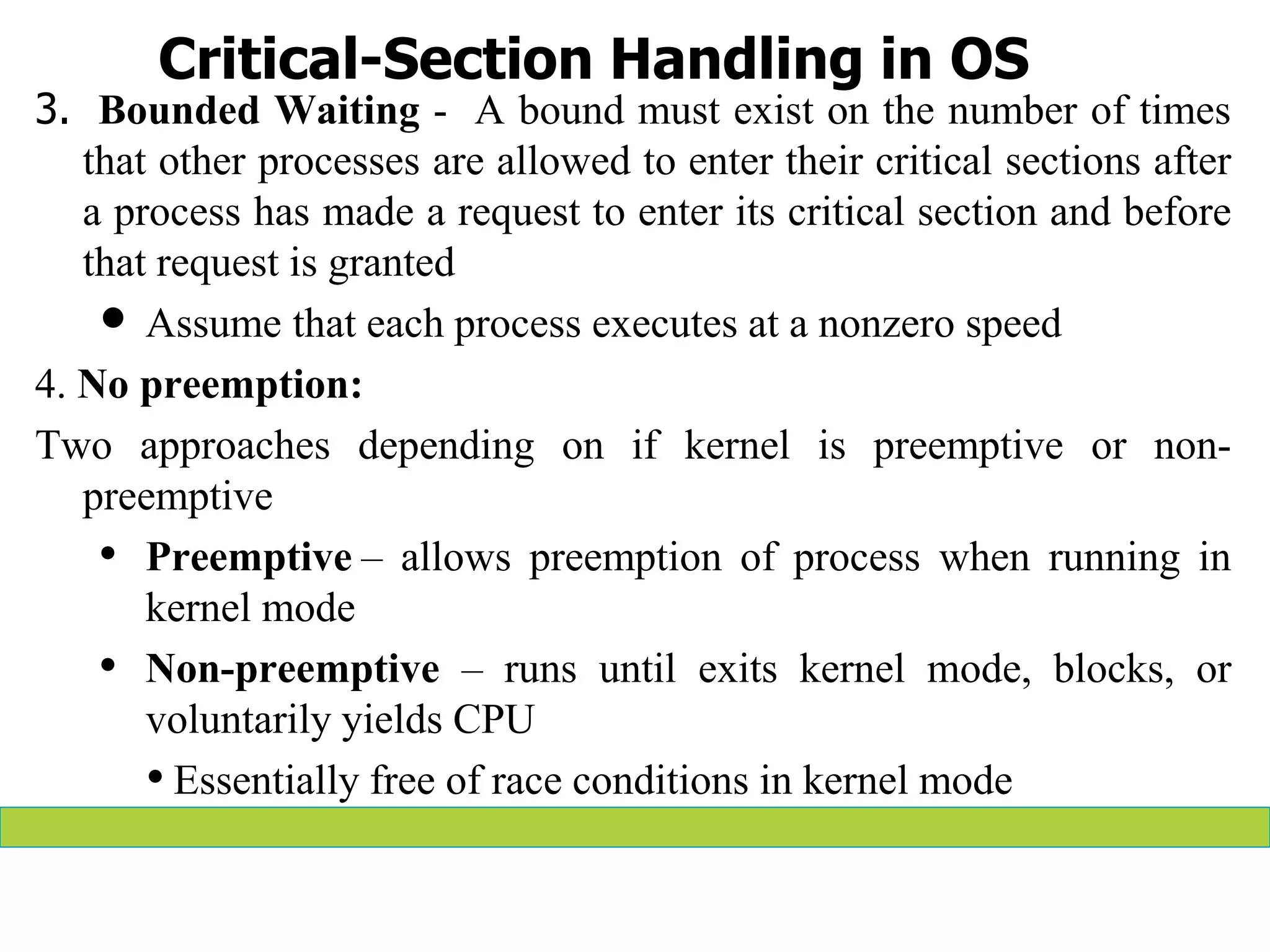

• To enter the critical section, process Pi first sets flag[i] to be true

and then sets turn to the value j, thereby asserting that if the

other process wishes to enter the critical section, it can do so.

• If both processes try to enter at the same time, turn will be set to

both i and j at roughly the same time. Only one of these

assignments will last; the other will occur but will be overwritten

immediately.

• The eventual value of turn determines which of the two

processes is allowed to enter its critical section first.

January 4, 2023 13

Operating Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture5-processsynchronization1-230104191210-4e1c3fd4/75/Lecture-5-Process-Synchronization-1-pptx-13-2048.jpg)

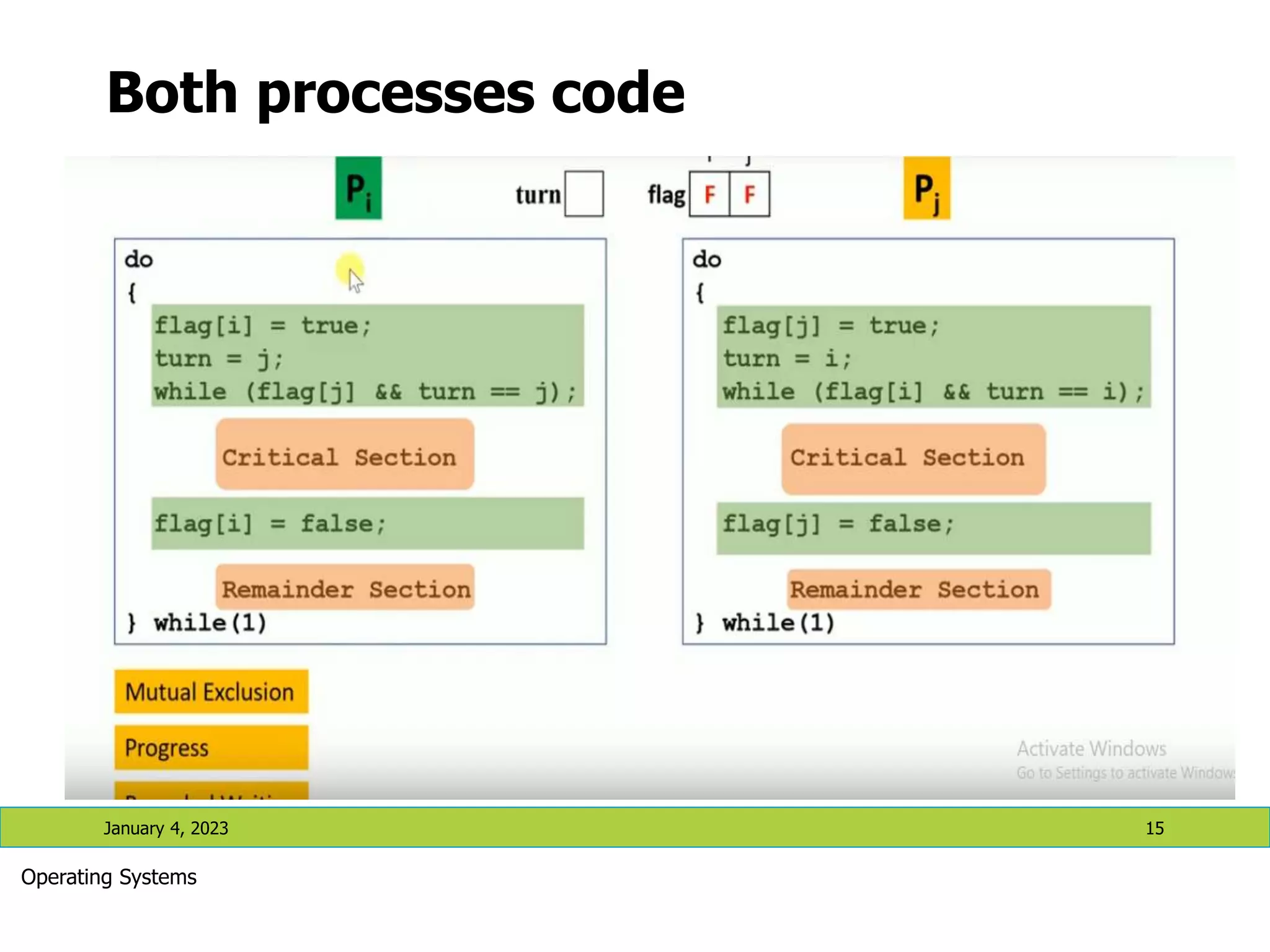

![Algorithm for Process Pi

do {

flag[i] = true;

turn = j;

while (flag[j] && turn = = j);

critical section

flag[i] = false;

remainder section

} while (true);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture5-processsynchronization1-230104191210-4e1c3fd4/75/Lecture-5-Process-Synchronization-1-pptx-14-2048.jpg)

![Cross check the guarantees

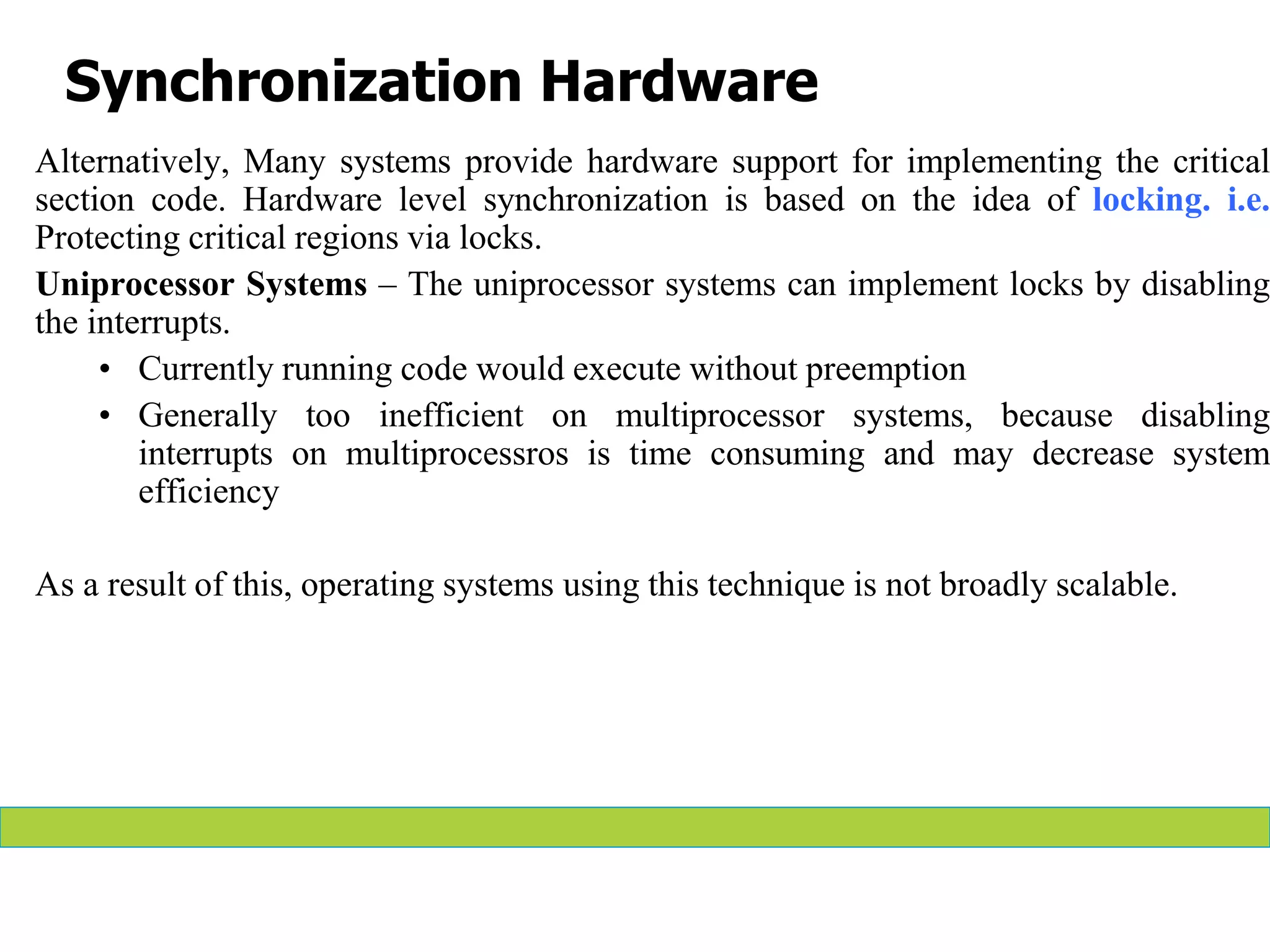

• In the Peterson’s Algorithm it can be Proved that the three

Critical Section requirement are fulfilled by this algorithm:

1. Mutual exclusion is preserved

Pi enters CS only if:

either flag[j] = false or turn = i

2. Progress requirement is satisfied

3. Bounded-waiting requirement is met

Limitation: All the algorithms discussed till now don’t work for N process critical section

problem. That’s why we design hardware based solutions to guarantee n process

synchronization.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture5-processsynchronization1-230104191210-4e1c3fd4/75/Lecture-5-Process-Synchronization-1-pptx-16-2048.jpg)

![Producer

while (true) {

/* produce an item in next produced */

while (counter == BUFFER_SIZE) ;

/* do nothing */

buffer[in] = next_produced;

in = (in + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

counter++;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture5-processsynchronization1-230104191210-4e1c3fd4/75/Lecture-5-Process-Synchronization-1-pptx-38-2048.jpg)

![Consumer

while (true) {

while (counter == 0)

; /* do nothing */

next_consumed = buffer[out];

out = (out + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

counter--;

/* consume the item in next consumed */

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture5-processsynchronization1-230104191210-4e1c3fd4/75/Lecture-5-Process-Synchronization-1-pptx-39-2048.jpg)

![Dining-Philosophers Problem

• Philosophers spend their lives alternating thinking and eating

• Don’t interact with their neighbors, occasionally try to pick up 2

chopsticks (one at a time) to eat from bowl

• Need both to eat, then release both when done

• In the case of 5 philosophers

• Shared data

• Bowl of rice (data set)

• Semaphore chopstick [5] initialized to 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture5-processsynchronization1-230104191210-4e1c3fd4/75/Lecture-5-Process-Synchronization-1-pptx-45-2048.jpg)

![Dining-Philosophers Problem Algorithm

• The structure of Philosopher i:

do {

wait (chopstick[i] );

wait (chopStick[ (i + 1) % 5] );

// eat

signal (chopstick[i] );

signal (chopstick[ (i + 1) % 5] );

// think

} while (TRUE);

• What is the problem with this algorithm?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture5-processsynchronization1-230104191210-4e1c3fd4/75/Lecture-5-Process-Synchronization-1-pptx-46-2048.jpg)

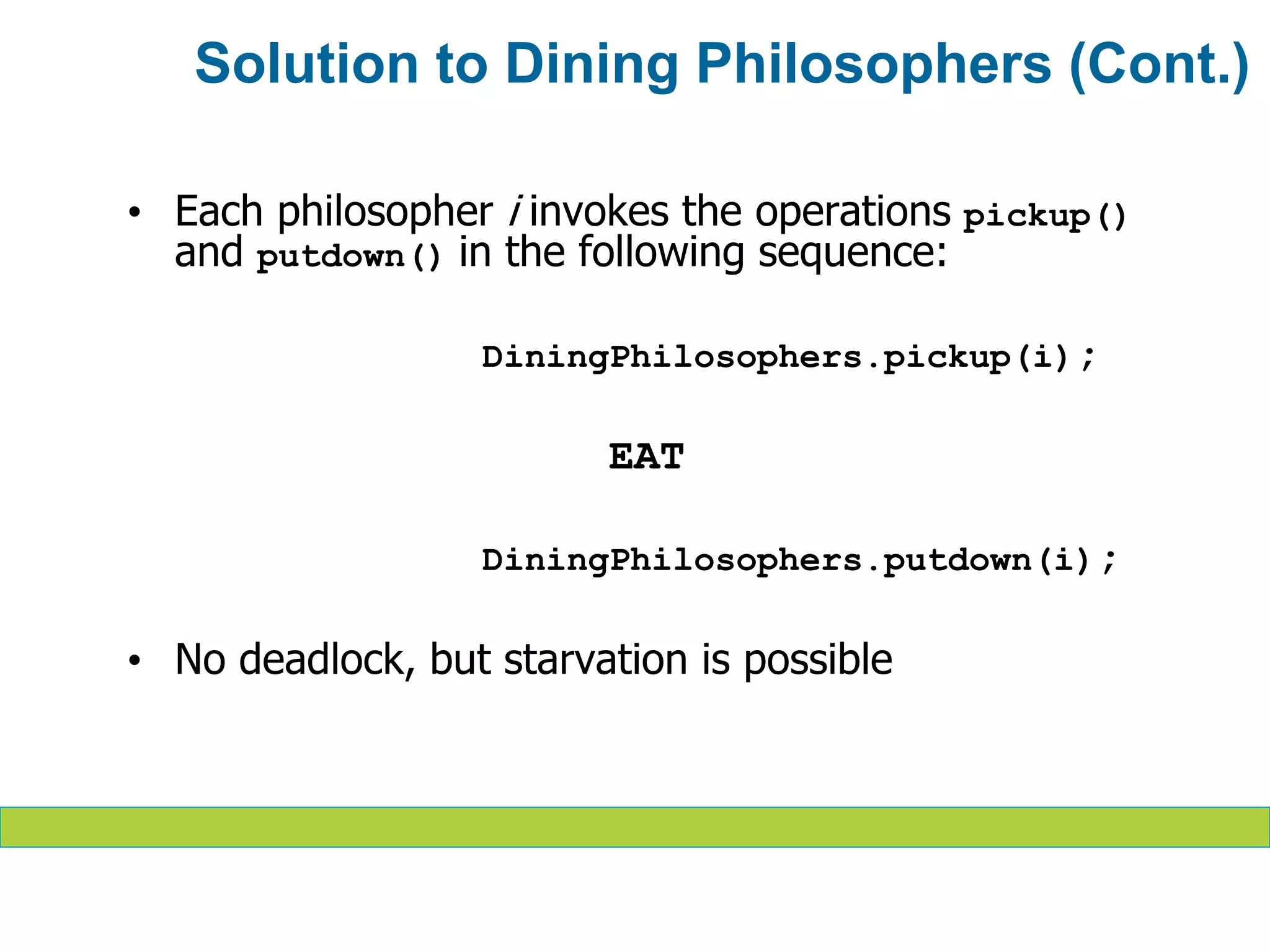

![Monitor Solution to Dining Philosophers

monitor DiningPhilosophers

{

enum { THINKING; HUNGRY, EATING) state [5] ;

condition self [5];

void pickup (int i) {

state[i] = HUNGRY;

test(i);

if (state[i] != EATING) self[i].wait;

}

void putdown (int i) {

state[i] = THINKING;

// test left and right neighbors

test((i + 4) % 5);

test((i + 1) % 5);

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture5-processsynchronization1-230104191210-4e1c3fd4/75/Lecture-5-Process-Synchronization-1-pptx-54-2048.jpg)

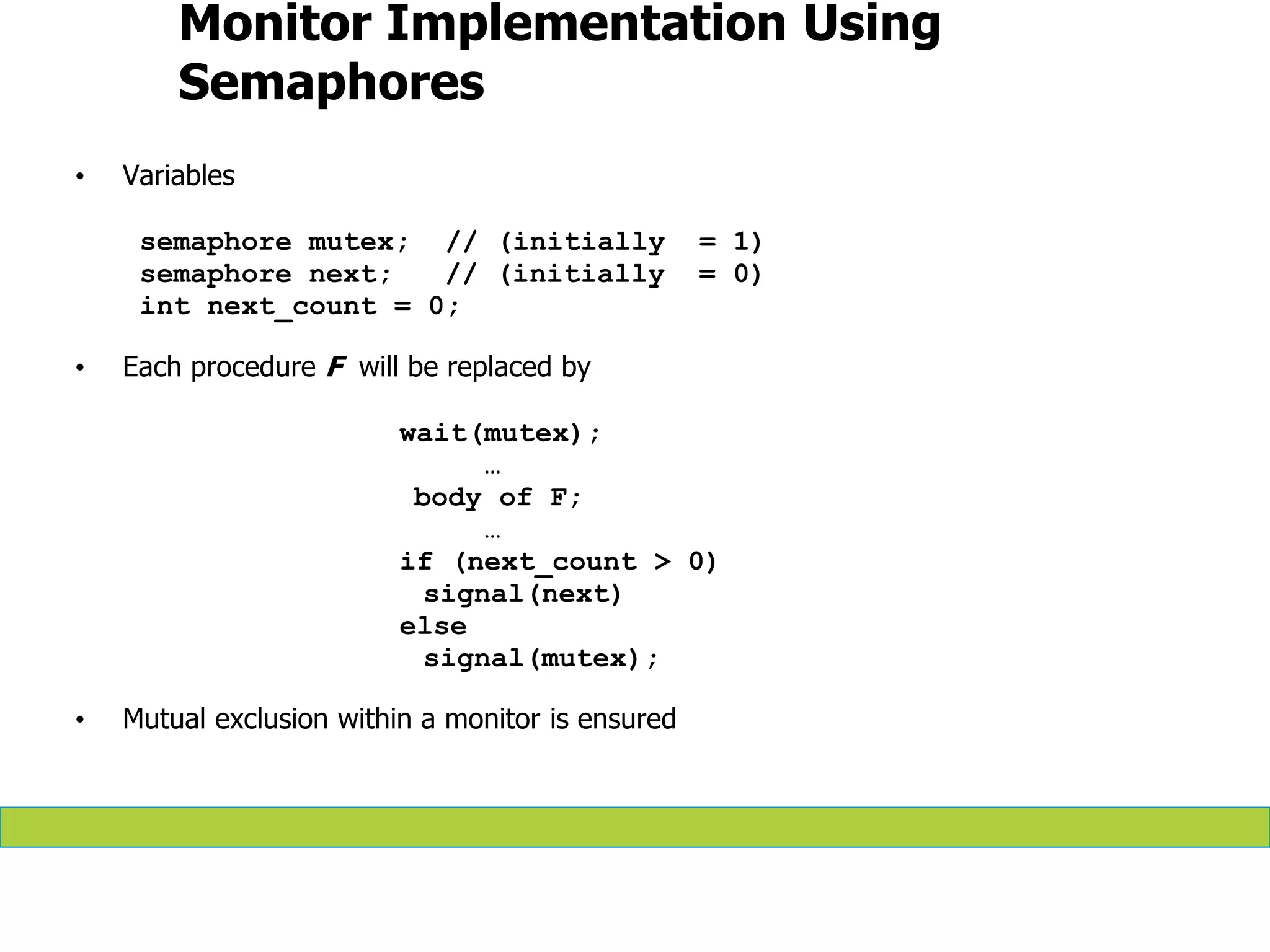

![Solution to Dining Philosophers

(Cont.)

void test (int i) {

if ((state[(i + 4) % 5] != EATING) &&

(state[i] == HUNGRY) &&

(state[(i + 1) % 5] != EATING) ) {

state[i] = EATING ;

self[i].signal () ;

}

}

initialization_code() {

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++)

state[i] = THINKING;

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture5-processsynchronization1-230104191210-4e1c3fd4/75/Lecture-5-Process-Synchronization-1-pptx-55-2048.jpg)