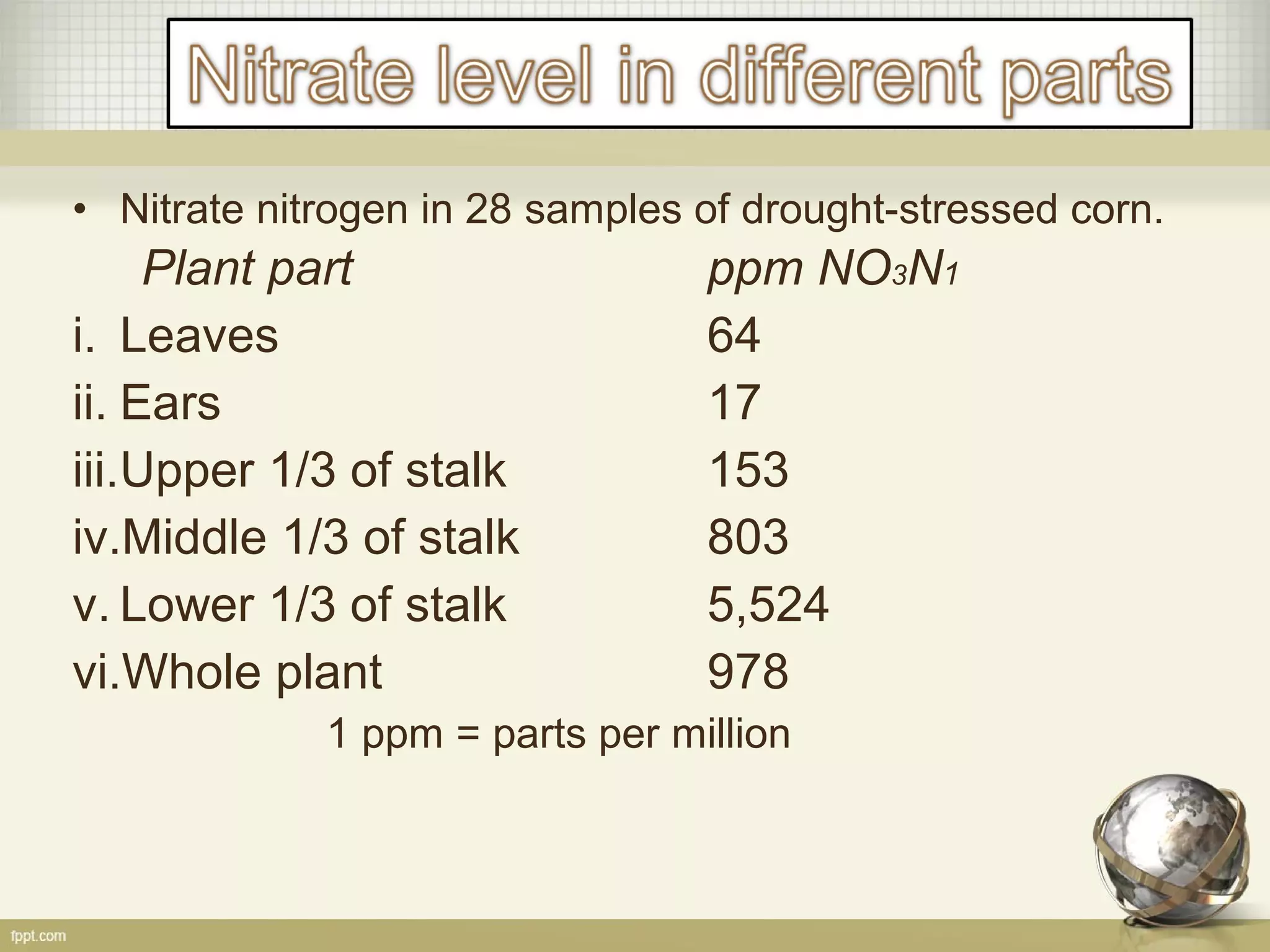

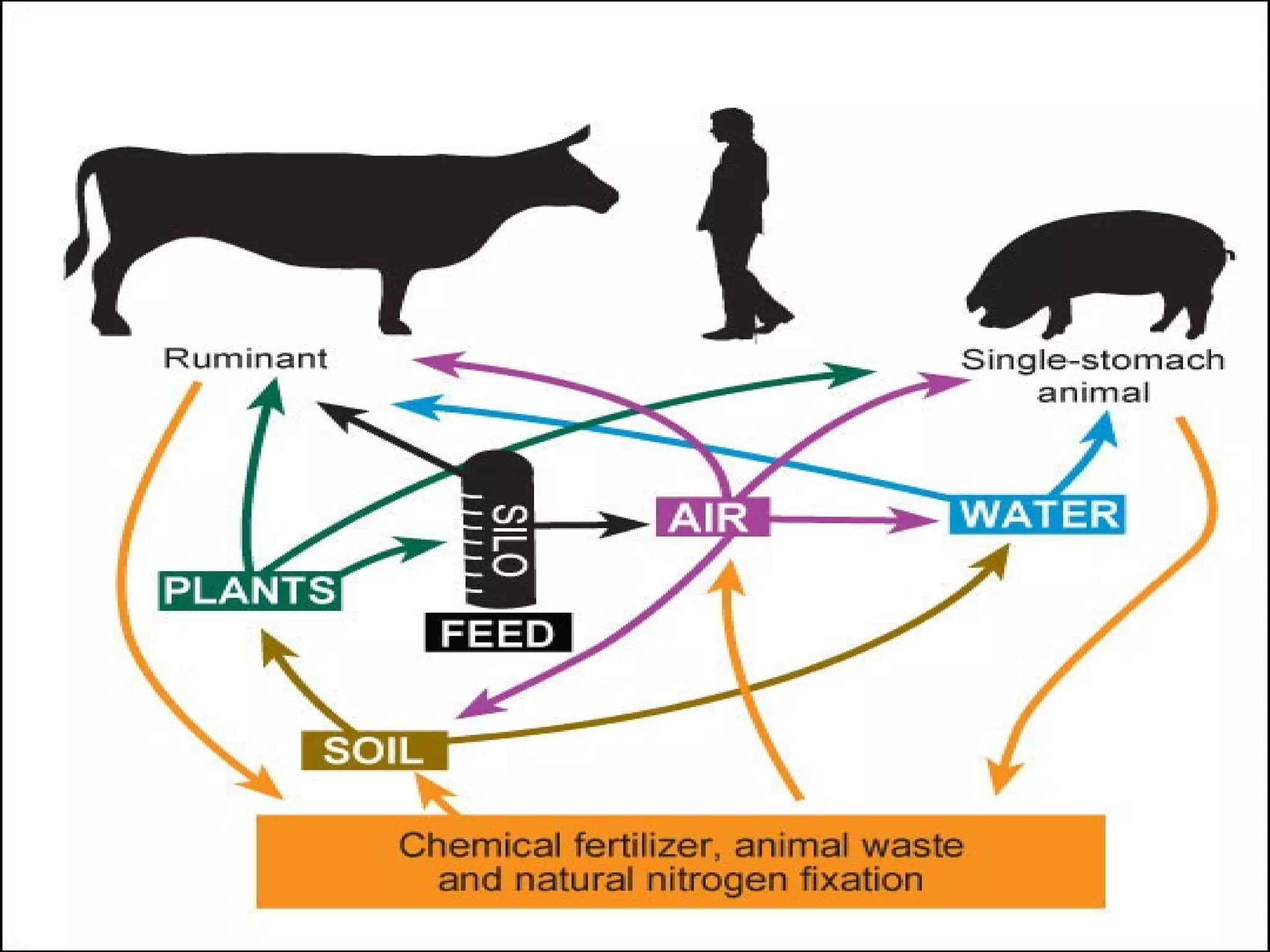

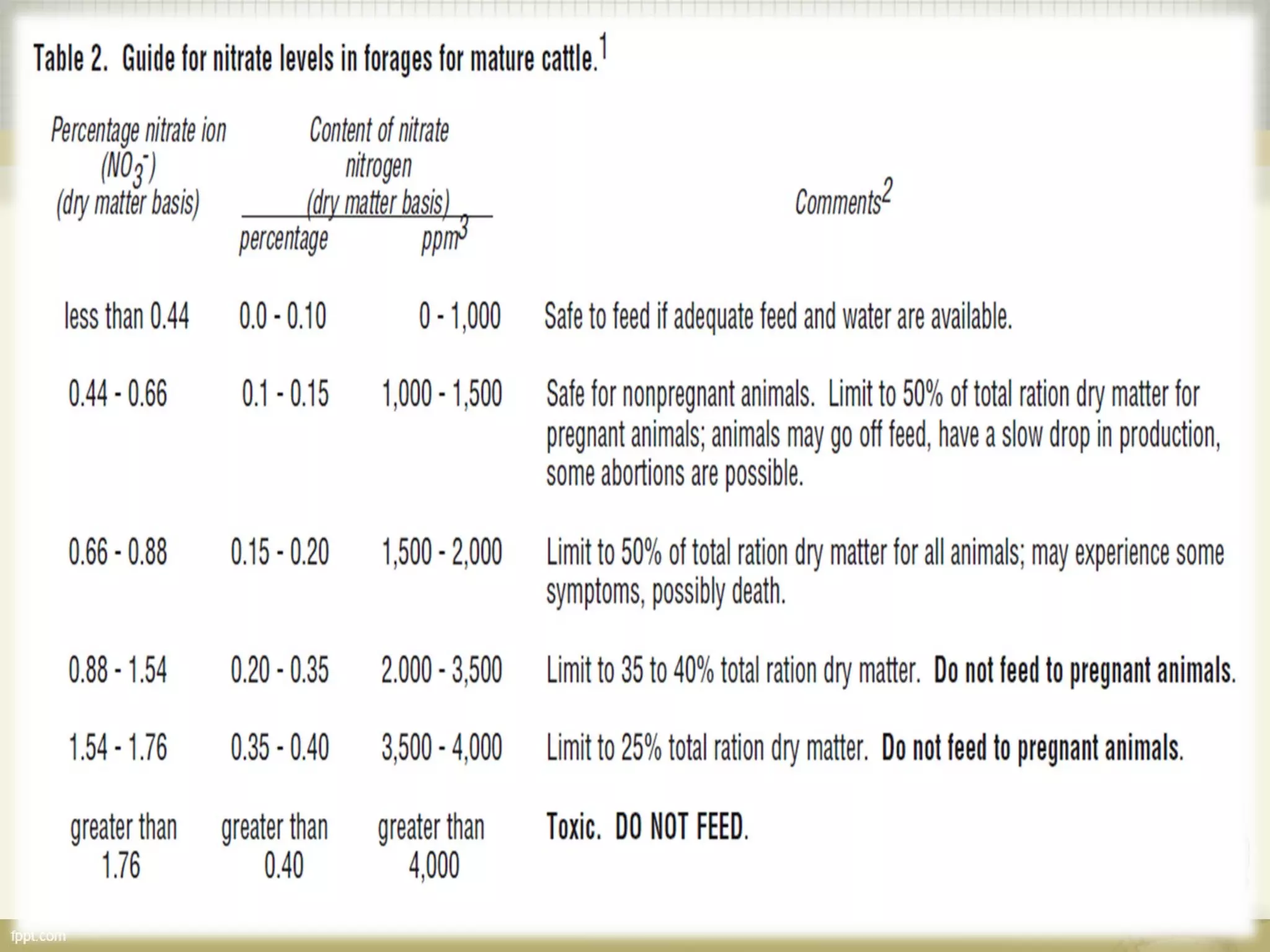

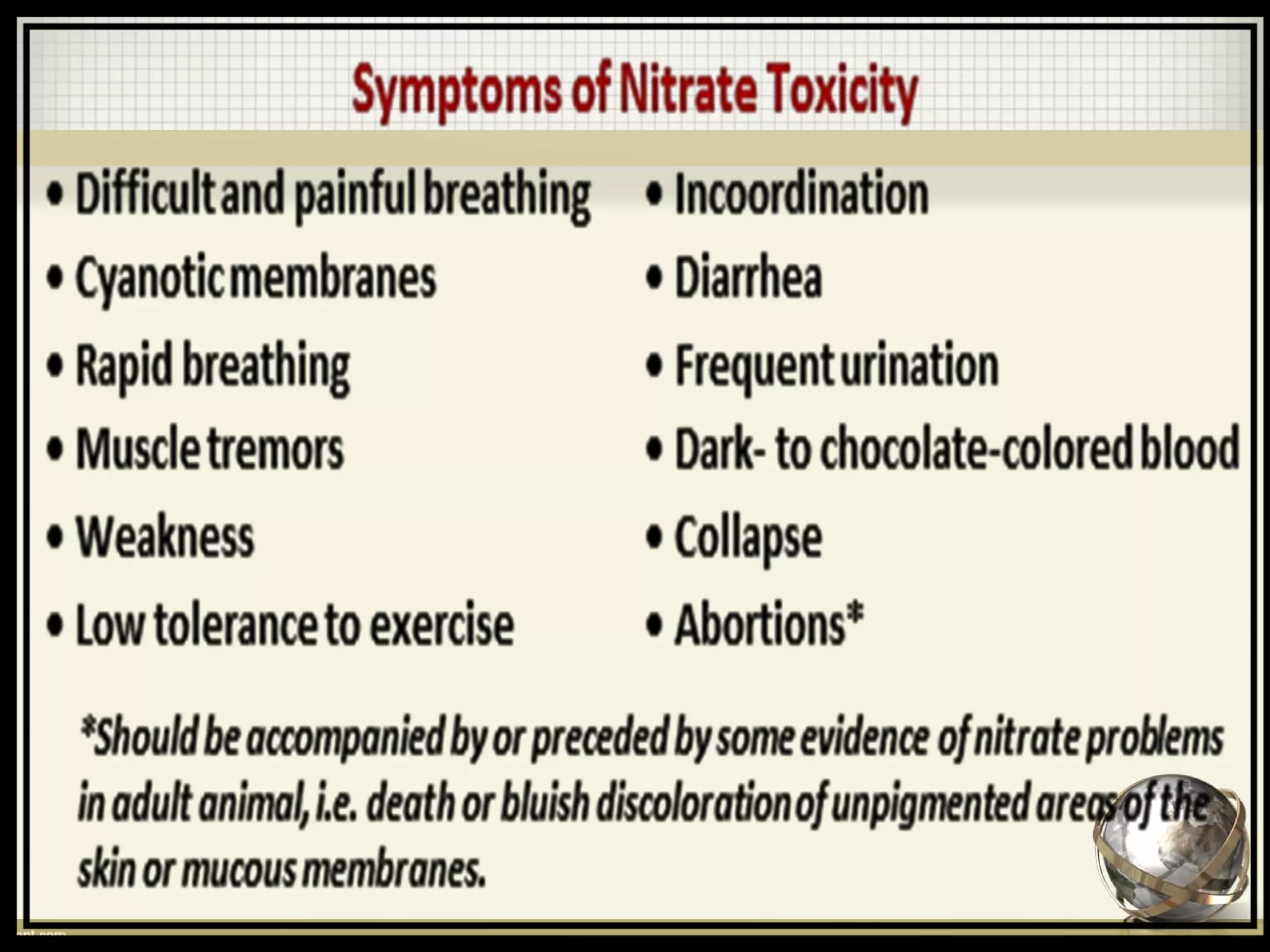

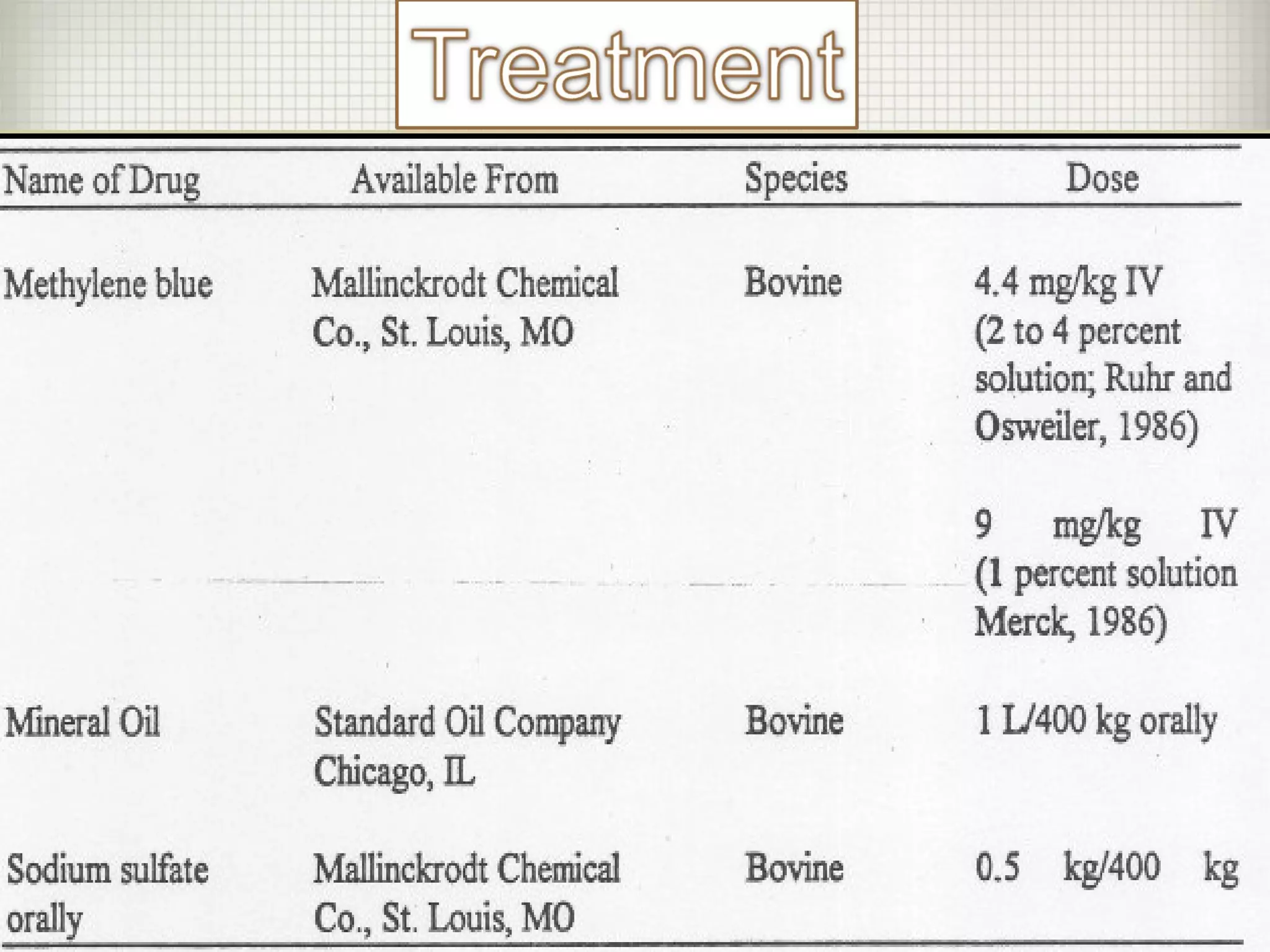

Nitrate poisoning in animals can occur when they consume forages high in nitrates under certain stress conditions. The nitrates interfere with oxygen transport in the blood, causing clinical signs like brown mucous membranes and eventually collapse. Testing forages using the diphenylamine spot test can help identify nitrate issues, with positive results requiring quantitative analysis. Managing nitrogen fertilizer application and harvesting forages at full maturity can help minimize nitrate accumulation. Affected animals may require veterinary treatment with methylene blue to restore oxygen carrying capacity in their blood. Proper testing and management of high-nitrate feeds can prevent nitrate poisoning in livestock.