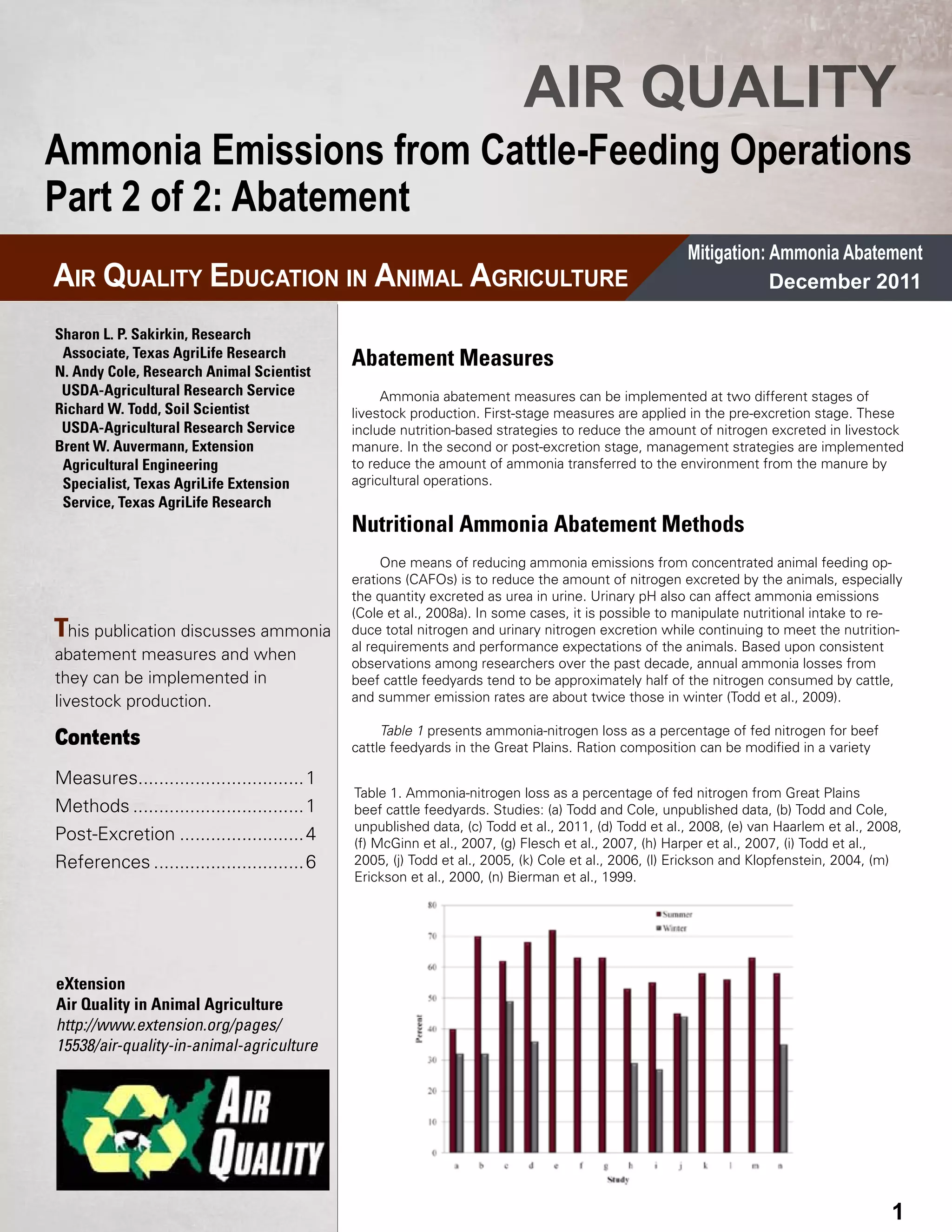

This document discusses ammonia abatement measures that can be implemented at livestock operations. It describes how nutritional strategies can reduce the amount of nitrogen excreted by livestock, such as decreasing crude protein levels and implementing phase feeding as cattle mature. Post-excretion, improving manure management through techniques like pen cleaning, covering storage areas, and immediate soil incorporation can also decrease ammonia emissions. While some measures may impact costs or animal performance, many options exist to significantly lower ammonia levels with only small effects.