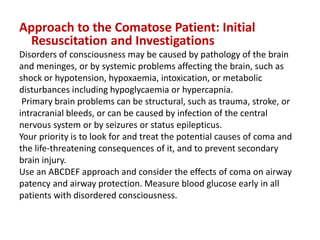

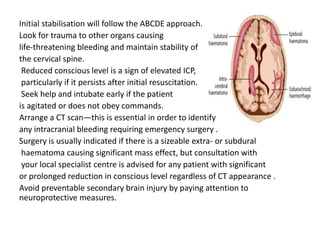

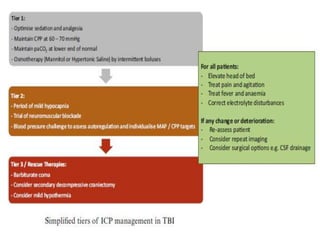

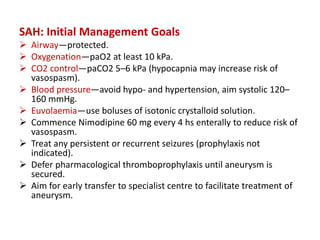

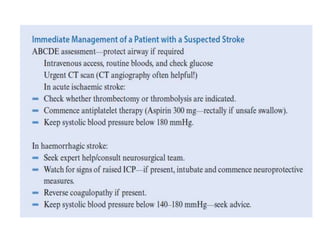

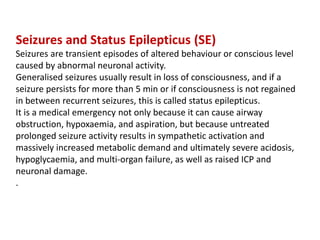

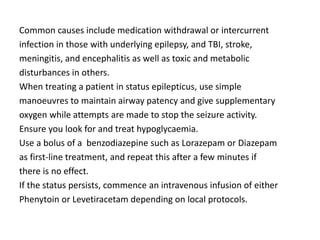

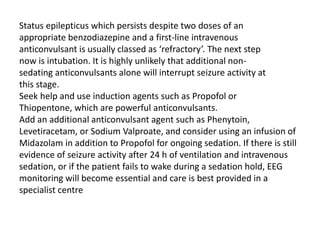

Dr. Rania Gashan's approach to managing comatose patients emphasizes identifying and addressing the underlying causes of consciousness disorders, using an ABCDEF method to prioritize airway protection and monitoring. Key interventions include early intubation, monitoring intracranial pressure (ICP), and managing systemic factors such as blood pressure and oxygenation to prevent secondary brain injury. The document also covers treatment protocols for various conditions like traumatic brain injury, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and strokes while emphasizing the importance of specialized care and timely imaging.