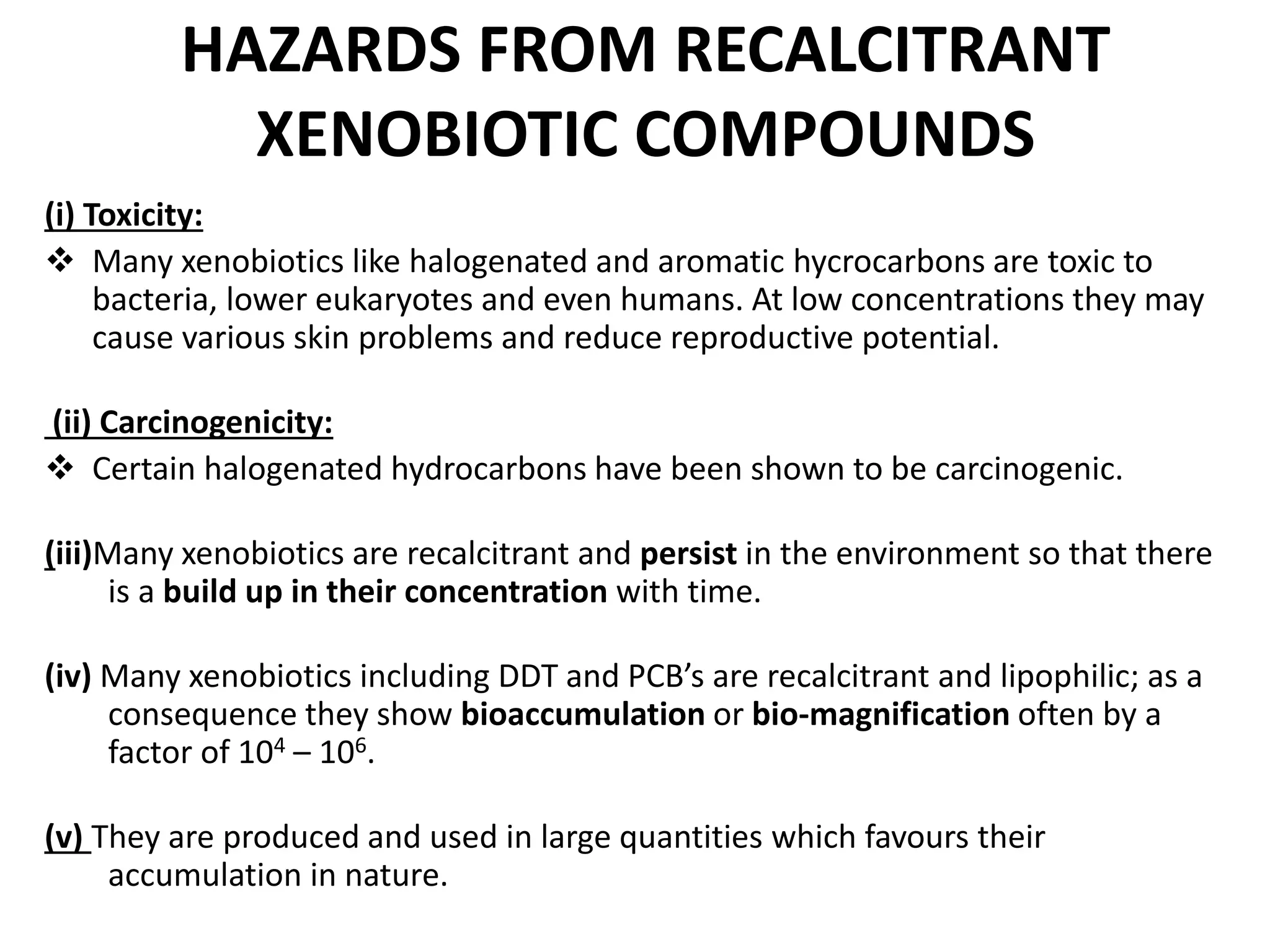

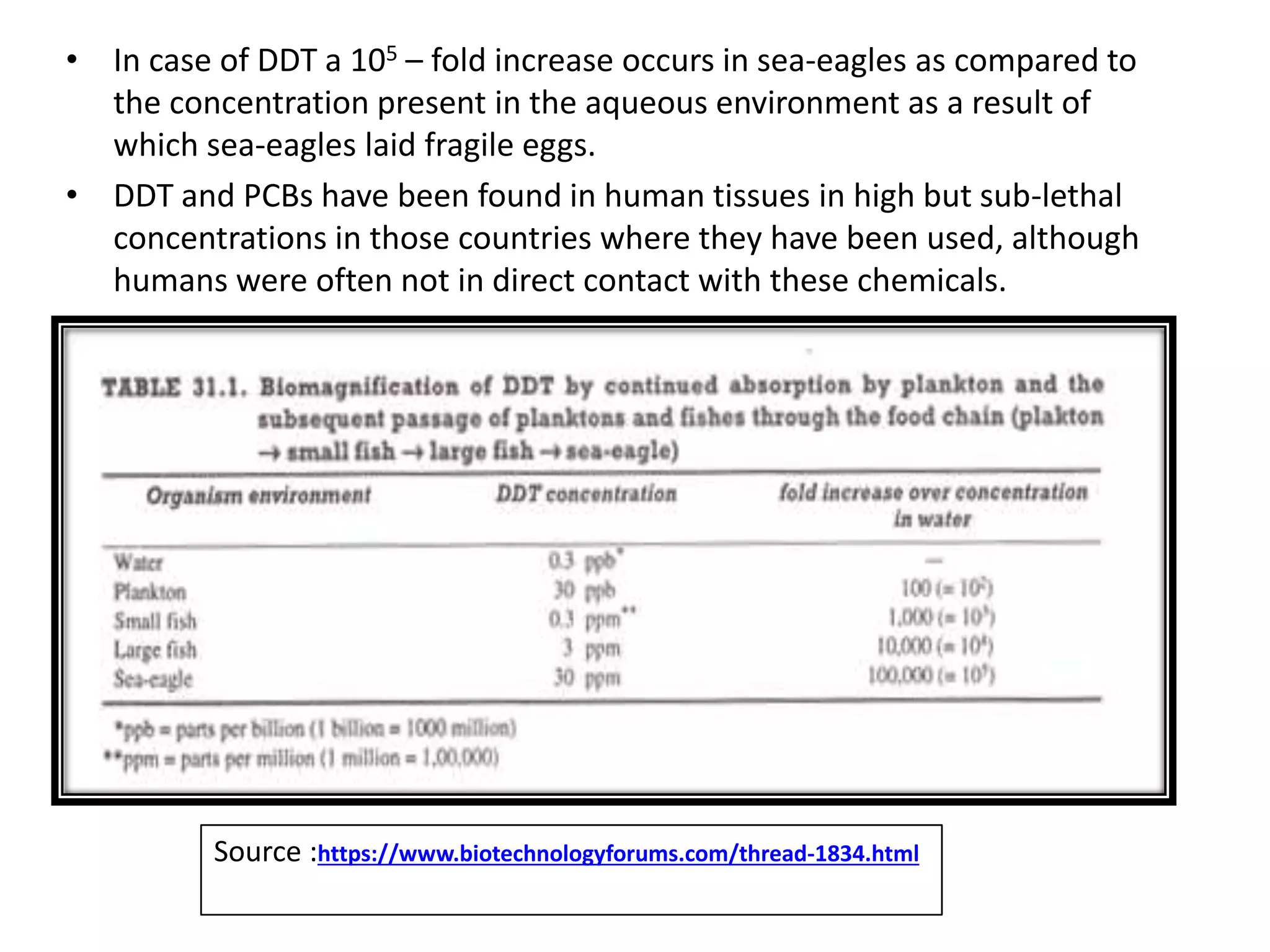

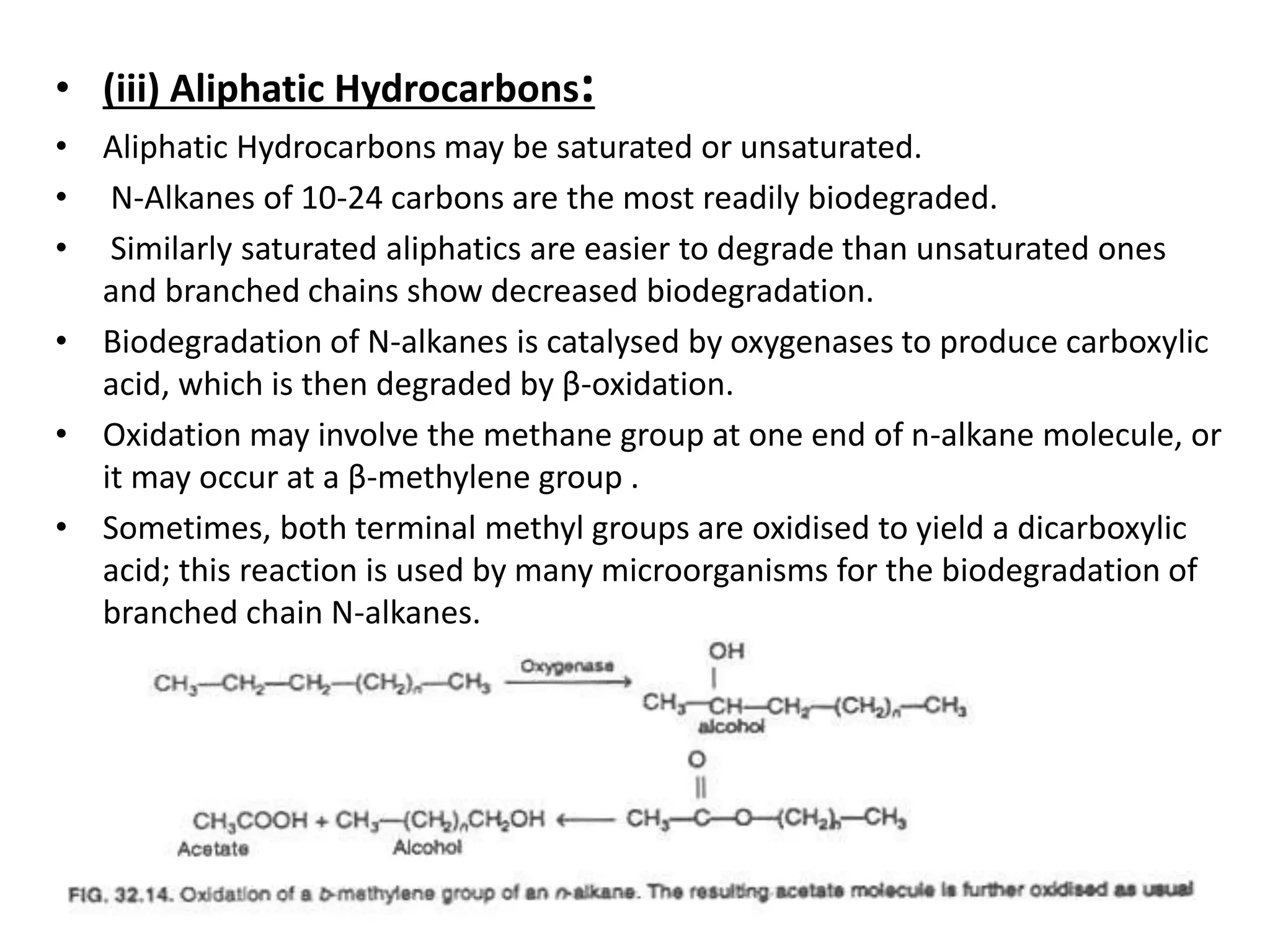

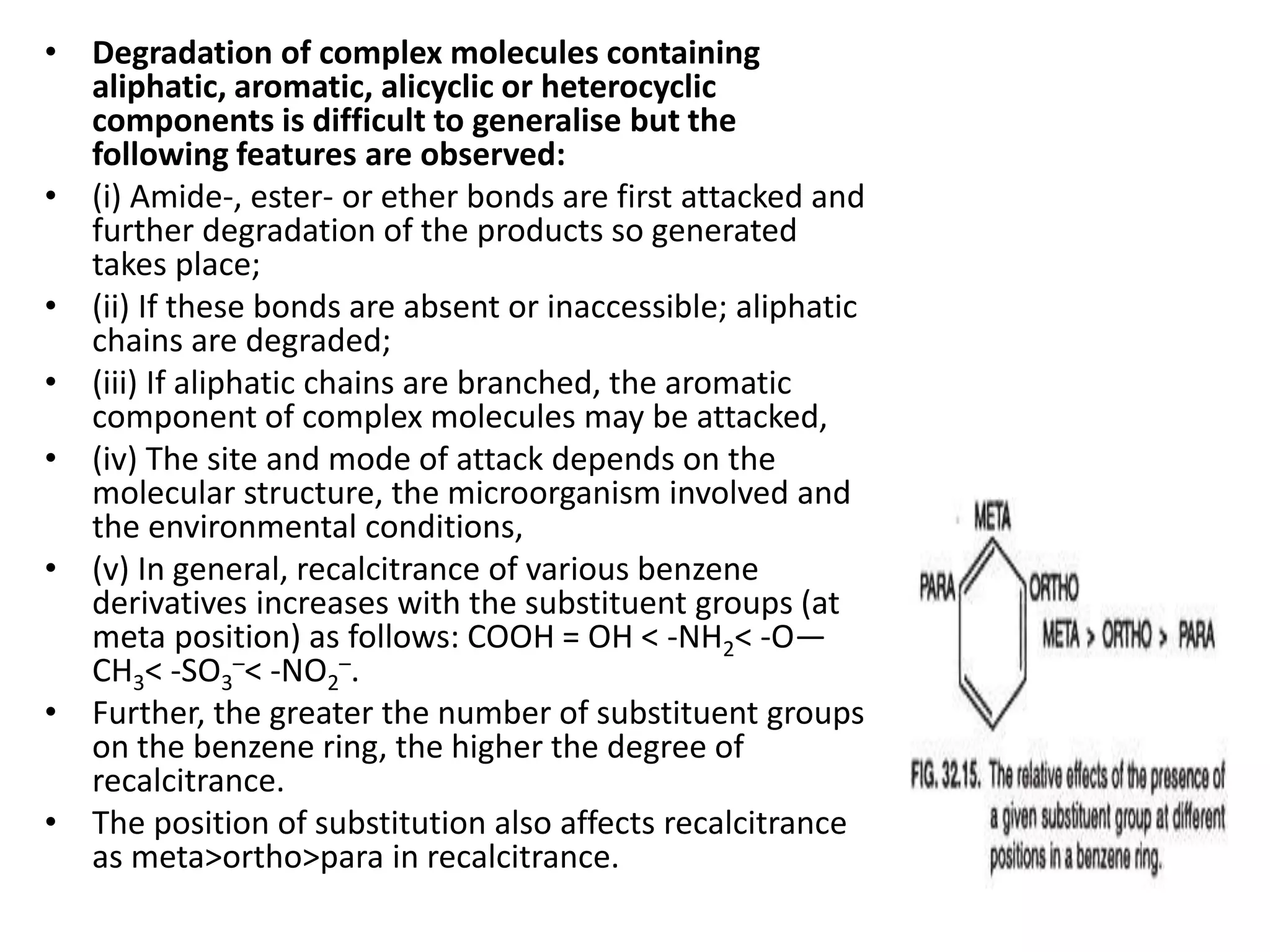

The document discusses microbial degradation of recalcitrant xenobiotic compounds, highlighting their persistence in the environment and associated health hazards. It categorizes these compounds, explains their degradation pathways using microorganisms, and emphasizes practical applications of microbes for remediation efforts. The text also details the structural characteristics that contribute to the recalcitrance of these compounds and the mechanisms by which microbial degradation occurs.