The document discusses various methods for estimating cost functions, including both short run and long run techniques, such as regression analysis and engineering cost approaches. It provides examples of cost estimates for firms like Boeing and utilities, and includes discussions on break-even analysis and the degree of operating leverage. Additionally, it touches on the learning curve effect in production processes.

![Slide 17

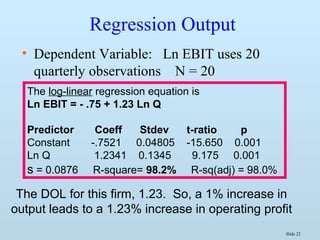

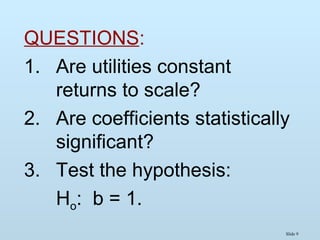

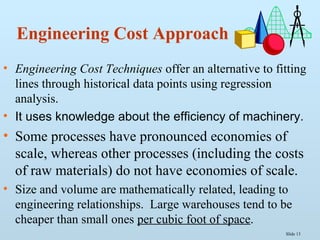

• Amount of sales

revenues that breaks

even

• P•QB/E = P•[F/(P-v)]

= F / [ 1 - v/P ]

Break-even Sales Volume

Variable Cost Ratio

Ex: At Q = 20,

B/E Sales Volume is

$9,000•20 =

$180,000 Sales Volume

Answer: Q = 40,000/(2,000)= 40/2 = 20

garages at the break-even point.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/me09-140429095149-phpapp02/85/Chapter-9-Application-of-Cost-Theory-17-320.jpg)

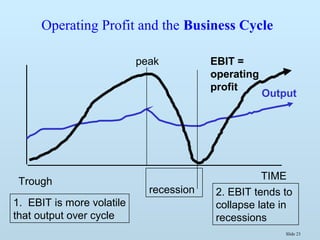

![Slide 18

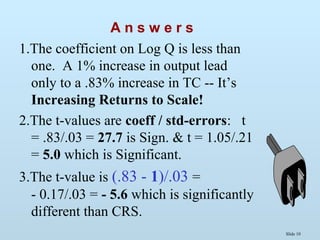

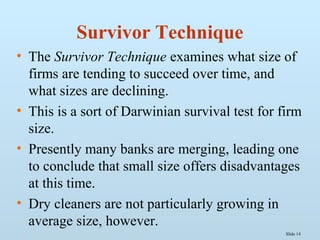

Target Profit Output

Quantity needed to attain a target

profit

If π is the target profit,

Q target π = [ F + π] / (P-v)

Suppose want to attain $50,000 profit, then,

Q target π = ($40,000 + $50,000)/$2,000

= $90,000/$2,000 = 45 garages](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/me09-140429095149-phpapp02/85/Chapter-9-Application-of-Cost-Theory-18-320.jpg)

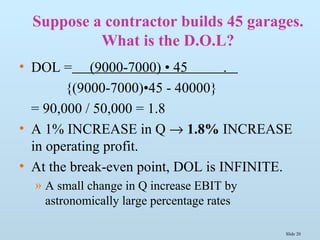

![Slide 19

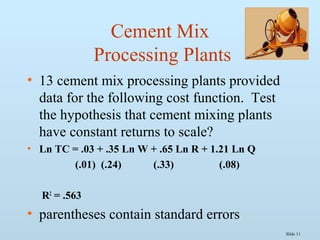

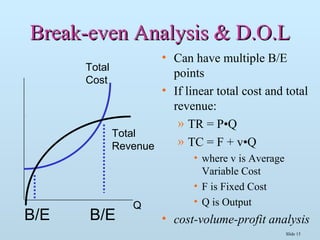

Degree of Operating Leverage

or Operating Profit Elasticity

• DOL = Eπ

» sensitivity of operating profit (EBIT) to

changes in output

• Operating π = TR-TC = (P-v)•Q - F

• Hence, DOL = ∂ π/∂ Q•(Q/π) =

(P-v)•(Q/π) = (P-v)•Q / [(P-v)•Q - F]

A measure of the importance of Fixed Cost

or Business Risk to fluctuations in output](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/me09-140429095149-phpapp02/85/Chapter-9-Application-of-Cost-Theory-19-320.jpg)

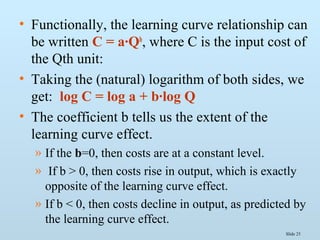

![Slide 21

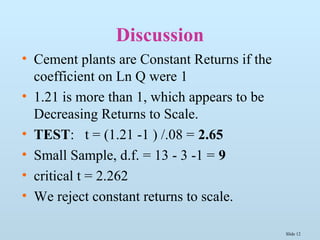

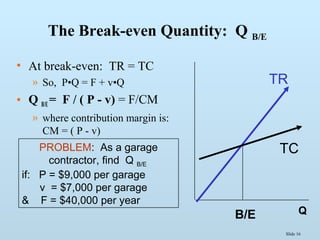

DOL as

Operating Profit Elasticity

DOL = [ (P - v)Q ] / { [ (P - v)Q ] - F }

• We can use empirical estimation methods to find

operating leverage

• Elasticities can be estimated with double log

functional forms

• Use a time series of data on operating profit and

output

» Ln EBIT = a + b• Ln Q, where b is the DOL

» then a 1% increase in output increases EBIT by b%

» b tends to be greater than or equal to 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/me09-140429095149-phpapp02/85/Chapter-9-Application-of-Cost-Theory-21-320.jpg)