This document discusses views on the long-term value of e-learning objects and materials. While there has been significant investment in e-learning over the past decades, the failure of many initiatives to take root in higher education has damaged credibility. E-learning objects are seen as having less clear boundaries than traditional resources. Standards need to be established to define e-learning concepts and ensure quality. Respondents expressed more confidence in traditional resources than digital materials. However, use of digital resources is trending upward. Care must be taken to consider pedagogical issues and develop models for effective reuse of e-learning resources.

![Long Term Retention and Reuse of E-Learning Objects and Materials

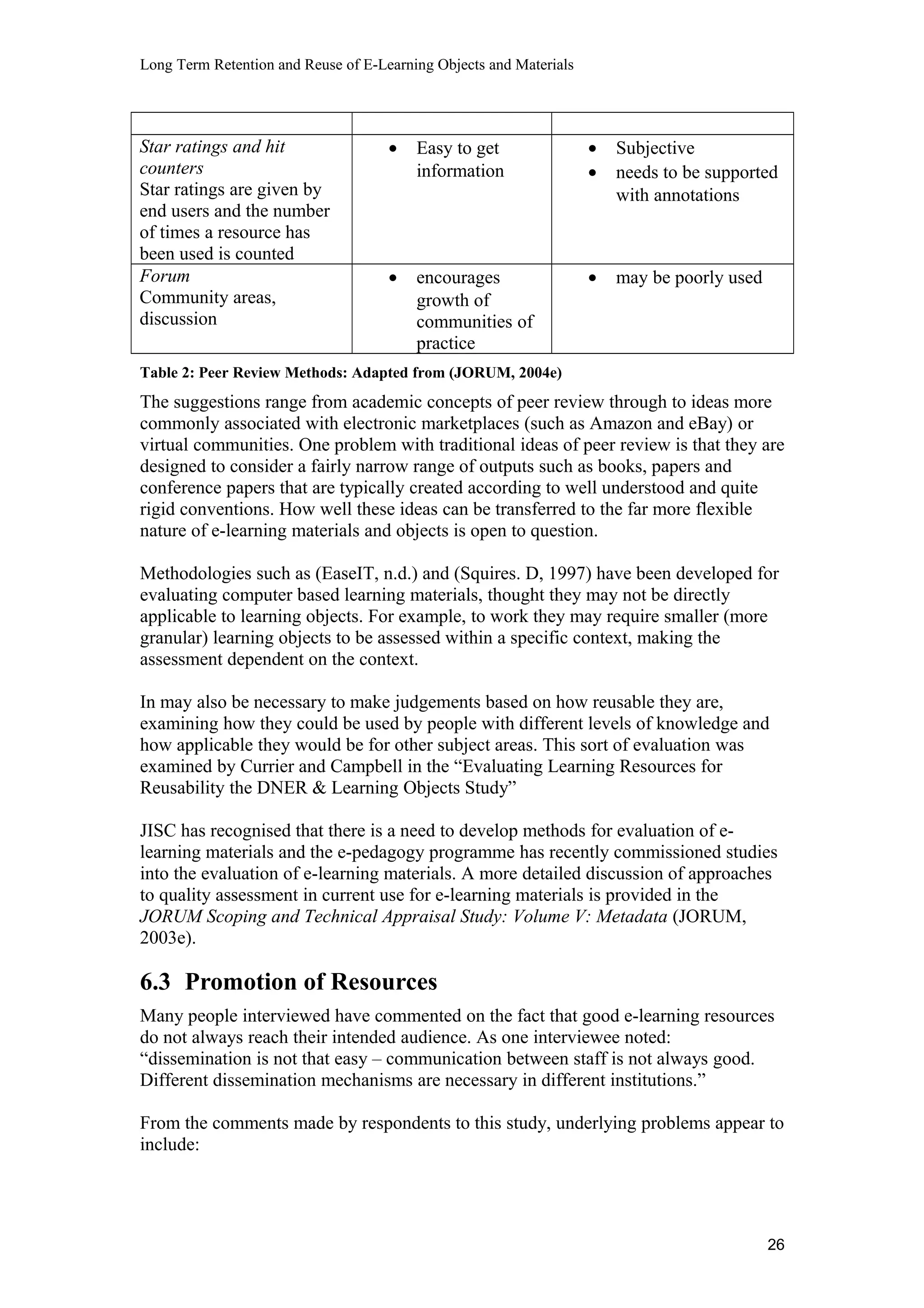

2 Recommendations

2.1 List of Recommendations

The report contains the following recommendations.

Recommendation 1

JISC should ensure that all e-learning materials created under JISC funded

programmes are available without restriction to UK HE and FE.

Recommendation 2

The failure of many e-learning initiatives to take root in higher and further education

is a significant concern. JISC should investigate the causes of this failure further.

Future funding for e-learning initiatives should include a requirement for projects to

include an evaluation of usage so that problems can be more readily identified and

lessons applied to subsequent activities.

In-depth comparative studies of successful and unsuccessful e-learning resources

should be commissioned.

Recommendation 3

Work has been done by the JISC Online Repository for [Learning and Teaching]

Materials (JORUM) study (JORUM, 2004e) into methods that the end user could use

to obtain information about the quality of a learning object. Further research is now

needed into methods for measuring the quality of learning objects.

Recommendation 4

A model licence for sharing e-learning material should be developed.

• Particular attention should be paid to protecting the moral rights of the

original creator.

• Licence terms should ensure that standard digital preservation strategies, such

as file format migration, are not precluded.

• Data protection and copyright issues over user feedback (potentially a

valuable source of quality assessment information) need to be addressed.

Recommendation 2

Guidelines for creating reusable e-learning materials have been developed by the

National Learning Network (NLN), Paving the Way document (NLN, n.d.), Ferl and

Exchange for Learning Programme (X4L) Healthier Nation (X4L, n.d.). Work should

be undertaken to determine if these and other guidelines can be amalgamated into a

single best practice guide for UK HE and FE.

Recommendation 6

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ltrstudyv1-4-181202113205/75/Long-Term-Retention-and-Reuse-of-E-Learning-Objects-and-Materials-6-2048.jpg)

![Long Term Retention and Reuse of E-Learning Objects and Materials

4 Views on the Long-Term Value of E-Learning

Objects and Materials

Since the 1990s there has been a persistent effort, pursued through an array of

initiatives, to promote learning technology in UK Higher and Further Education (HE

and FE). Major past activities include the Information Technology Training Initiative

(ITTI) and the Teaching & Learning Technology Programme (TLTP). Other

activities, such as the Fund for the Development of Teaching and Learning (FDTL)

continue. JISC programmes, such as the JISC Technology Applications Programme

(JTAP) and the 5/99 Learning and Teaching Programme have sought to investigate

and develop the technological framework needed to manage and deliver e-learning

content.

Mention must be made also of the NLN, which is one of the most significant

contributions to e-learning in the UK and is “designed to increase the uptake of

Information and Learning Technology … across the learning and skills sector in

England” (NLN, N.D.).

Like many new concepts, e-learning has been oversold on occasion and this has

created unrealistic expectations about how quickly and dramatically traditional

approaches to learning might be transformed. The failure to live up to earlier

hyperbole around e-learning has damaged the credibility of e-learning developments

within much of the academic community, as a number of respondents (focus group

and interviews) to this study observed:

• “Hype is often necessary to get funding for e-learning projects”

• “Digital resources can mutate and lose provenance quickly”

• “E-learning objects have fuzzy boundaries unlike paper resources”

• “Communities can not agree on definitions for e-learning concepts”

• “At the moment learning object systems have taken bad learning practices and

solidified – do not encourage group work.”

In general, the focus groups and interviews conducted for this study suggest that there

is still “far greater confidence in books than [in e-]learning materials”. However,

despite this view, respondents to both this study and to the JORUM scoping study

also noted that there is a trend towards greater use of digital resources in learning and

teaching:

• “Just about every FE college in Scotland has a VLE strategy”

• “There is a move towards VLEs in Universities”

• “E-Journals are being used more”

Deliberate efforts have been made to ensure that the technological innovations of e-

learning are embedded into wider professional practice. In the second phase of the

Computers in Teaching Initiative (CTI), for example, 24 subject specific centres were

established "to maintain and enhance the quality of learning and increase the

effectiveness of teaching through the application of appropriate learning technologies"

(Martin, 1996). In 2000, the CTI Centres were replaced by the Learning and Teaching

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ltrstudyv1-4-181202113205/75/Long-Term-Retention-and-Reuse-of-E-Learning-Objects-and-Materials-11-2048.jpg)

![Long Term Retention and Reuse of E-Learning Objects and Materials

(UMI) serves as a cautionary example. The initiative funded 19 projects and ended in

1998. Of those 19 projects, only four project websites are still available. Following

the UMI programme, SHEFC (Scottish Higher Education Funding Council) funded

19 projects under the ScotCIT (C & IT Programme of the Scottish Higher Education

Funding Council) programme. Nearly all the websites for these projects are still

available, but most do not appear to have been developed, or actively maintained

since funding for the projects ended.

As one respondent said: “There is some urgency here. As well as funding new

projects it is important to keep old ones [we] need to bring attention to the fact that

resources are being lost”. One learning technologist thought that saving resources

from past projects could “help the e-learning community build on resources rather

than the stop, start cycle which has been happening”.

Nevertheless, one of the conclusions drawn from the focus groups held by the

JORUM project was that “archiving of materials is a low priority for the community

and more research into digital preservation is necessary before this should be

considered” (JORUM, 2004c, pg 31). Interviewees for this study made similar

comments, noting the low awareness of the issues involved in keeping resources over

a long period.

Overseeing ongoing activities such as rights management, version control and

metadata maintenance could involve considerable costs. As respondents to the

JORUM scoping study observed, “no one wants responsibility for storage”; “who are

guardians, who takes charge?” Doubts were voiced by some respondents to the

JORUM scoping study and this study about the ability of institutions to take on the

management of e-learning materials:

• “Institutions lack a well defined structure to support the use of E-Learning

Materials”

• “Some institutions have a lot better attitude towards resource management

than others”

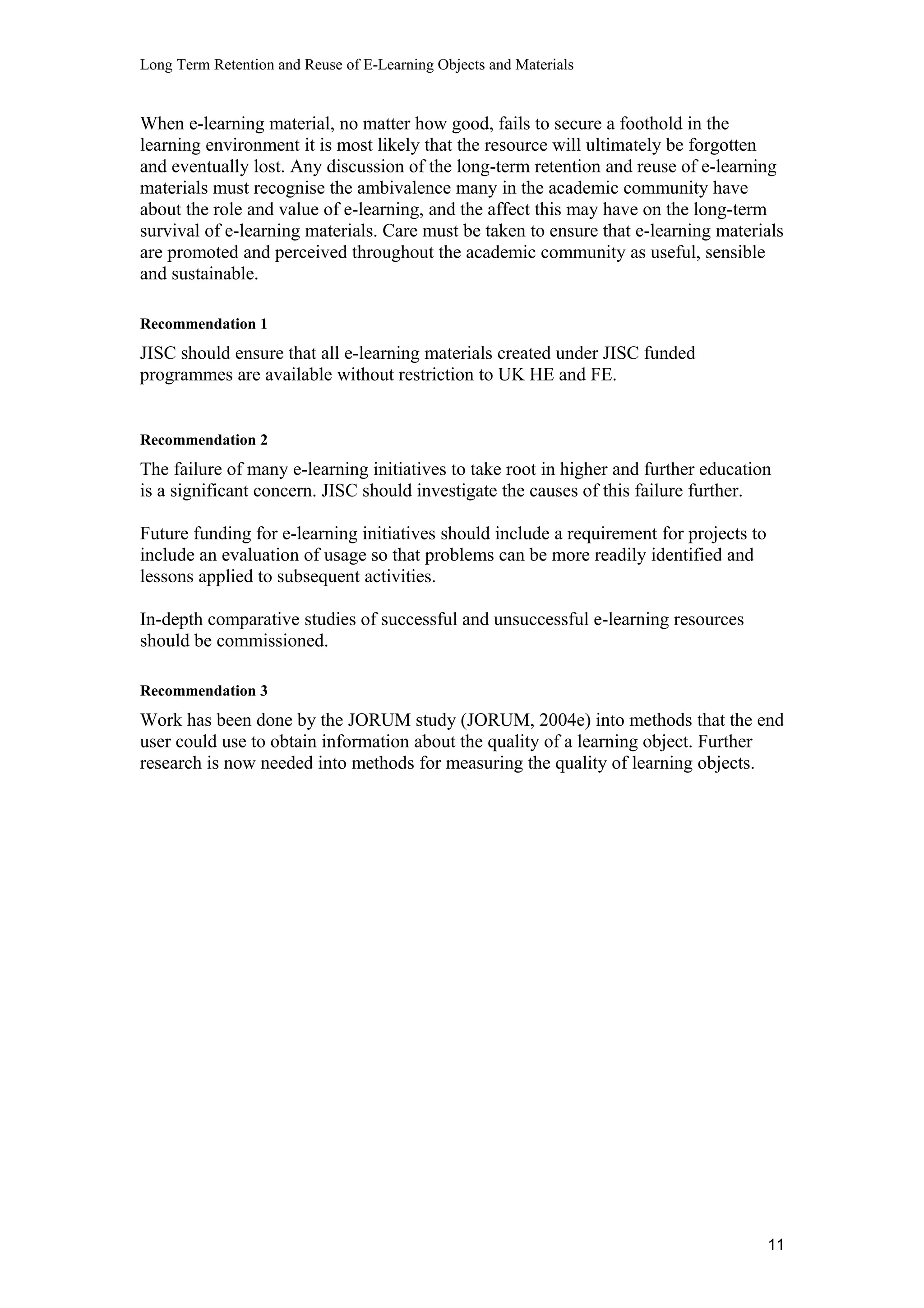

Regardless of these problems, there are issues that may well force institutions into

establishing means of retaining e-learning materials and objects. The record retention

schedules developed for higher education institutions by JISC (Parker, 2003) provide

a detailed overview of recommended practice for the retention of institutional records,

including those related to the preparation, delivery and assessment of teaching. The

guidance most directly relevant to e-learning materials is reproduced in Table 1. In

particular, there is a need to:

• Keep final versions of taught course materials available for the life of the

course and review for archival purpose

• Keep final versions of taught course assessments for the duration of the course

and review for archival purpose

• Keep taught course assessments completed by the student for the current

academic year + 1 year

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ltrstudyv1-4-181202113205/75/Long-Term-Retention-and-Reuse-of-E-Learning-Objects-and-Materials-13-2048.jpg)

![Long Term Retention and Reuse of E-Learning Objects and Materials

learning, but which lacks the additional connotations of accessibility, interoperability

and especially reusability that are typically associated with learning objects (Polsani,

2003).

5.2 Design Principles for Reusability

The definition of a learning object adopted in this report is intentionally broad. This is

done in an effort to avoid tying the report to any one view on how best to promote

reusability in e-learning. Many different approaches are currently being used to

develop e-learning materials for reuse, and they are dependent on the aims of the

creators and the audience they are designing for. For example, the MIT

OpenCourseWare project does not currently enforce a learning object type approach

for the teaching and learning content and material is made freely available on the

Internet. Conversely, the Curve project (CURVE, N.D.) at The Open University is

designed to be used internally and consists of well defined learning objects tagged

with IMS learning object metadata.

The range of different resource types that can be used in e-learning combined with

evolving techniques and standards for describing, storing and delivering e-learning

content are causing much confusion within the e-learning community. Worryingly, as

Wiley has noted:

The vast majority of existing digital educational resources cannot be

reused in current learning objects systems supposedly designed

specifically to support reusability.

Wiley (N.D.)

Maintaining any type of digital resource is, in the long-term, easier when due

attention has been given to relevant standards and good practices during the creation

of the resource (Jones & Beagrie, 2001). Retroactively improving digital resources so

that they can be deployed outside of the originally conceived context is a time

consuming and costly business. As Currier and Campbell observe:

In terms of developing reusable content, the major factor for success

that this part of DNER&LO [study] appears to highlight is the need for

planning at the start of an e-learning initiative for the considerable

amount of effort and expertise that must go into creating truly reusable

content.

(Currier and Campbell, 2002)

Elsewhere, Campbell (2003a) has identified the key factors that affect the reusability

of learning objects as granularity, technical dependency and content dependency.

These three factors all, in different ways, measure the sensitivity of a learning object

to the particular technical and pedagogical environment it is used in, and thus they in

large measure determine the potential for reusing e-learning objects in both the short

and long-terms.

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ltrstudyv1-4-181202113205/75/Long-Term-Retention-and-Reuse-of-E-Learning-Objects-and-Materials-17-2048.jpg)

![Long Term Retention and Reuse of E-Learning Objects and Materials

In addition information about how to use the resource could also be useful to the end

user. In particular, the IMS Learning Design specification is for describing resource

use in a pedagogically neutral manner so that lesson plans can be exchanged in an

accepted way. Although it is currently at an early stage of development, the JISC e-

learning and pedagogy programme is investigating its use.

More information about metadata issues is covered in (JORUM, 2004d)

5.3.2 Preservation Metadata

Preservation metadata … is the information necessary to maintain the

viability, renderability, and understandability of digital resources over

the long-term. Viability requires that the archived digital object’s bit

stream is intact and readable from the digital media upon which it is

stored. Renderability refers to the translation of the bit stream into a

form that can be viewed by human users, or processed by computers.

Understandability involves providing enough information such that the

rendered content can be interpreted and understood by its intended

users.

OCLC (2002)

In addition to descriptive metadata, a preservation metadata schema will include

components of administrative, structural and technical metadata. Administrative

metadata includes information about the provenance and rights associated with the

digital resource. Structural metadata is used to describe the internal organisation of

the items in a digital resource. Technical metadata includes information about the

formats, software and hardware used by the resource.

Several digital preservation metadata schemas and standards have emerged over

recent years, most notably from the digital library community (National Library of

Australia, 1999; CEDARS, N.D.; California Digital Library, 2001; National Library

of New Zealand, 2002). The devolvement of the Open Archival Information System

(OAIS) Reference Model has spurred development of digital preservation metadata in

this context (Lupovici & Masanès, 2000; Online Computer Libraries Center [OCLC],

2002).

Different factors, primarily the drive for interoperability, are behind developments in

e-learning metadata specifications. It is possible, however, to view the problem of

digital preservation as an interoperability problem; that is, how can we ensure that the

digital resources of today can interoperate with the digital resources of tomorrow. The

emphasis in e-learning standards on interoperability is therefore a good basis for

ensuring the long-term survival of e-learning material.

Interoperability is also an issue for the digital library community where the metadata

interoperability standard METS (Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard -

METS, 2003a) has received international attention (METS, 2003b). METS is

essentially a container format into which descriptive and other metadata can be

loaded. It also includes a native capability for structural metadata. The Library of

Congress, and other organisations, are investigating the use of METS in relation to the

OAIS reference model, highlighting the close links between information needed for

interoperability and that need for preservation (METS, 2003b).

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ltrstudyv1-4-181202113205/75/Long-Term-Retention-and-Reuse-of-E-Learning-Objects-and-Materials-22-2048.jpg)

![Long Term Retention and Reuse of E-Learning Objects and Materials

2004c). There is however, a mismatch between this enthusiastic endorsement of the

JORUM learning repository concept and other, more doubtful sentiments, expressed

by respondents to both this study and the JORUM scoping study:

• “If it’s worth something, why make it free?”

• “Institutions will keep the good stuff for themselves and put the dross online”

• “There are many people interested in sharing, but others [are] interested in

profit”

• “Having learning objects for sale could prove fatal to the sharing ideology”

• “Do we want to follow [the] overpriced text book model?”

Many respondents felt that incentives were lacking to encourage individuals to make

e-learning materials freely available to others. As one person put it, “what is the

incentive for the individual – more work and no gain”.

On a national level many people interviewed have expressed concern that good

materials are not getting as many end users as they should be. In particular, many of

those materials have not been designed for reuse using a learning object approach and

by doing so reuse may be improved.

Both individual and institutional incentives will be necessary to encourage the sharing

and reuse of e-learning materials. Many suggestions about how to create these

incentives were made during both this study and the JORUM scoping study. Given

the difficulty of accurately valuing reusable learning materials (OLCL, 2003, p.8), it

is not surprising that a central feature of most of the suggestions made is the

establishment of a mechanism that will enable e-learning material users, or their

proxies, to judge the value of e-leaning materials and feed their assessment back to e-

learning creators. Possibilities include: the creation of a ‘prestige’ economy, direct

monetary reward, credits towards learning and teaching Curriculum Vitae for

individuals, or a system similar to the Research Assessment Exercise. There was no

consensus among respondents to this study about which approach would be most

likely to succeed, but it is clear that any model for sharing and reusing e-learning

materials must, at the least, address a number of underlying considerations, including

Intellectual Property Rights (IPR), the creation and maintenance of resource discovery

metadata, and quality assurance.

6.2.1 Intellectual Property Rights

IPR is a potential issue in two ways. If sharing and reuse is based on some kind of

money based market, then e-learning materials will need to be accompanied by clear

IPR information that can be used to facilitate rights clearance. Even if e-learning

materials are made available at no cost, perhaps through a licensing framework such

as the Creative Commons (Creative Commons, N.D.), which is used by the MIT

OpenCourseWare initiative (MIT, N.D.) for example, the ability to track rights, and

assure authors due recognition for their work will still be important. A particular

complication for e-learning objects may emerge when they are modified – raising the

question of how to apportion authorship.

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ltrstudyv1-4-181202113205/75/Long-Term-Retention-and-Reuse-of-E-Learning-Objects-and-Materials-28-2048.jpg)

![Long Term Retention and Reuse of E-Learning Objects and Materials

Berglund, Y., Morrison, A., Wilson, R. and Wynne, M. An Investigation into Free

eBooks. 2004. Accessed on 13 Mar 2004.

<http://www.ahds.ac.uk/litlangling/ebooks/index.html >

Biz/ed. Virtual Economy. N.D. Accessed on 13 Mar 2004.

< http://www.bized.ac.uk/virtual/economy/index.htm >

Boyle, T. Design principles for authoring dynamic re-usable learning objects

. 2002. Accessed on 15 Mar 2004.

<http://www.ics.ltsn.ac.uk/Learning_Objects/lmu_learningobjects/papers_pres/ASCI

LITE_slides_2002.ppt>

Boyle, T., Learning Objects for Introductory Programming. N.D.

<http://www.ics.ltsn.ac.uk/Learning_Objects/lmu_learningobjects/evaluation.htm>

Budd, A. Why websites look different in different browsers (or why pixel-perfect

design is not possible on the web). 2003. Accessed on 15 Mar 2004.

< http://www.message.uk.com/articles/display.php >

Calarks. ARKS Material. 2000. Accessed on 15 Mar 2004.

< http://homepages.ed.ac.uk/calarks/arks/materials.html >

California Digital Library [CDL]. Digital object standard: metadata, content and

encoding. 2001. Acccessed on May 3, 2003.

<http://www.cdlib.org/about/publications/CDLObjectStd-2001.pdf>

Campbell, L. Talk given at “The New Economy: Learning Objects” 2003. Accessed

on 15 Mar 2004.

< http://www.intrallect.com/news/seminar_powerpoint/lorna_campbell.ppt >

Campbell, L. Reusing Online Resources, Edited by Allison Littlejohn, Kogan and

Page, 2003.

Casey, J. Draft Document: Intellectual Property Rights and Networked E-Learning,

2003.

CCSDS, Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems [CCSDS] Reference model

for an open archival system, CCSDS 650.0-B-1 Blue Book. 2002. Accessed on 15 Mar

2004.

< http://www.ccsds.org/documents/650x0b1.pdf >

CEDARS (N.D.). Metadata for digital preservation: the Cedars Project outline

specification. Accessed on May 3, 2003.

<http://www.leeds.ac.uk/cedars/colman/metadata/metadataspec.html>

Cedars Project. Cedars Guide to Digital Collection Management. 2002. Accessed on

18 Dec 2003.

< http://www.leeds.ac.uk/cedars/guideto/collmanagement/guidetocolman.pdf >

CETIS. CETIS Content Code Bash: Final Report. 2002. Accessed on 12 Mar 2004.

54](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ltrstudyv1-4-181202113205/75/Long-Term-Retention-and-Reuse-of-E-Learning-Objects-and-Materials-58-2048.jpg)

![Long Term Retention and Reuse of E-Learning Objects and Materials

OCLC. Libraries and the Enhancement of E-Learning. 2003. OCLC E-Learning Task

Force. Accessed on 11 Mar 2004.

<http://www5.oclc.org/downloads/community/elearning.pdf>

OCLC [Online Computer Library Center] (2002). Preservation Metadata and the

OAIS Information Model: A Metadata Framework to Support the Preservation of

Digital Objects. OCLC/RLG Working Group on Preservation Metadata. Accessed on

3 May 2003.

<http://www.oclc.org/research/pmwg/pm_framework.pdf>

OKI. What is the Open Knowledge InitiativeTM? 2002. Accessed on 15 Jan 2004.

< http://web.mit.edu/oki/learn/whtpapers/OKI_white_paper_120902.pdf >

Olivier, B. & Liber,O. Reusing Online Resources, Kogan & Page, 2003.

Open Archives Initiative. Open Archives Initiative Frequently Asked Questions

(FAQ). 2002. Accessed on 13 Mar 2004.

<http://www.openarchives.org/documents/FAQ.html#What%20do%20you%20mean

%20by%20an%20"Archive >

Oren, T. Original CompuServe announcement about GIF patent. 1995. Accessed on

18 Dec 2003.

< http://lpf.ai.mit.edu/Patents/Gif/origCompuServe.html >

PADI. Roles and responsibilities. N.D. Accessed on 13 Mar 2004.

< http://www.nla.gov.au/padi/topics/8.html >

Paulsen, M. F. Online Education Systems: Discussion and Definition of Terms.

Accessed on July 2002. Accessed on 15 Dec 2003.

< http://www.nettskolen.com/forskning/Definition%20of%20Terms.pdf >

Perry, S. et-al. THE CO3 PROJECT: Stretching the IMS Specifications to Achieve

Interoperability. 2002. Accessed on 12 Mar 2004.

< http://www.jisc.ac.uk/uploaded_documents/CO3Report_Final.doc >

Pinfield, S. Managing electronic library services: current issues in UK higher

education institutions. Ariadne no. 29. 2001. Accessed on 14 Mar 2004.

< http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue29/pinfield >

Planet PDF. Planet PDF Tools List. 2003. Accessed on 12 Mar 2004.

< http://www.planetpdf.com/mainpage.asp?MenuID=193&WebPageID=612 >

Polsani, P. R. Use and Abuse of Reusable Learning Objects. Journal of Digital

Information. Vol. 3, No. 4., 2003. Accessed on 8 Jun 2004.

< http://jodi.ecs.soton.ac.uk/Articles/v03/i04/Polsani/ >

RLG, Research Libraries Group [RLG]. Trusted Digital Repositories: Attributes and

Responsibilities. An RLG-OCLC Report. 2002. Accessed on 3 Mar 2004.

< http://www.rlg.org/longterm/repositories.pdf >

62](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ltrstudyv1-4-181202113205/75/Long-Term-Retention-and-Reuse-of-E-Learning-Objects-and-Materials-66-2048.jpg)

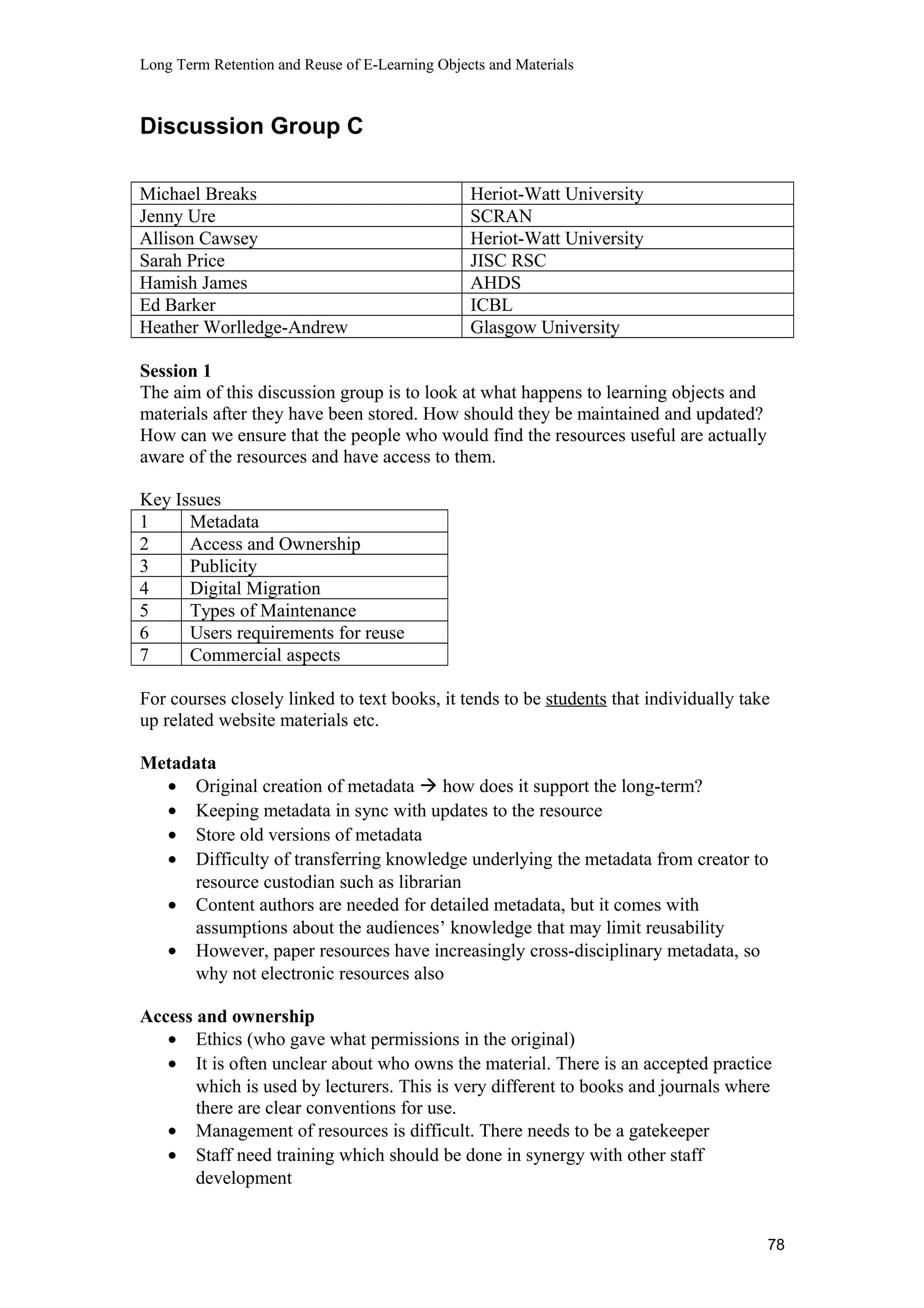

![Long Term Retention and Reuse of E-Learning Objects and Materials

• There are very different user groups. Some want large modules whereas others

would prefer to have small objects. We need to cater for both markets.

• Resources can get “worn out” if they are too publicised.

• Lack of credit and accreditation of original content creators in derivative

works

• Failure to seek permission, need to specify what is acceptable and what is not

• Are learning materials treated differently to publications?

• Seen as income generator, provide an institutional competitive advantage

o Restrictions on who can view and use resources, even within

institutions

o Opposite pressure to RAE (‘publish or perish’) as keeping e-learning

resources restricted may provide an income stream

• Need for enforcement or change of culture to allow reuse

o NLN free to use, CLIVE Vetinary science material sold at cost

o Whose budget are e-learning resources paid for from? Glasgow has a

core materials fund, but generally there is no central budget for e-

learning resources

o RAE style incentives?

Promotion and uptake of e-learning resources

• Need to promote e-learning materials to broaden usage, keeping in mind

maintenance and on-going support – not just initial effort

• Information overload and traditionalism act against the use of e-learning

resources, but there is a culture shift towards the use of more electronic

resources in learning and teaching [HJ: future sustainability issues?]

• No equivalent to publishing house publicity budgets exists

• Institutions lack a well-defined (and understood by staff) structure to support

the use of e-learning materials [HJ: technical support, password management,

subject knowledge etc may all be spread across different parts of the

organisations]

• Need to correctly target publicity

• Need to educate students and lecturers about good search strategies for finding

educational material

• Perhaps, e-books should be adopted as the best way of delivery e-learning

materials familiar concept with advantages of electronic medium

o Could query the rationale of e-learning objects: it is a core

responsibility of the lecturer to create and customise learning materials

for their students should they be using prepackaged learning objects

at all?

• HE has a craft based industry model

• Secondary user notes are added to original materials (in addition to metadata)

79](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ltrstudyv1-4-181202113205/75/Long-Term-Retention-and-Reuse-of-E-Learning-Objects-and-Materials-83-2048.jpg)