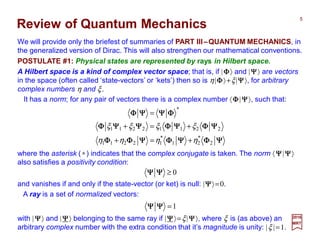

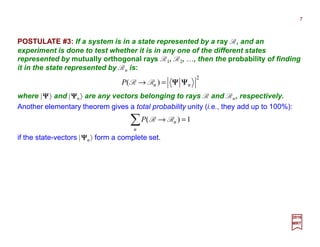

The document summarizes key concepts from quantum mechanics and symmetries. It states that physical states are represented by rays in a Hilbert space, with observables represented by Hermitian operators. The probability of measuring a state is given by the inner product of the state vectors. Symmetries are represented by either unitary or antiunitary operators on the Hilbert space. Symmetries that can be continuously connected to the identity must be represented by unitary operators. Symmetries form a group, with transformations combining according to the group multiplication rule.

![“A poet once said, ‘The whole universe is in a glass of wine.’ We will probably never know in what sense

he meant that, for poets do not write to be understood. But it is true that if we look at a glass of wine

closely enough we see the entire universe. There are the things of physics: the twisting liquid which

evaporates depending on the wind and weather, the reflections in the glass, and our imagination adds the

atoms. The glass is a distillation of the earth’s rocks, and in its composition we see the secrets of the

universe’s age, and the evolution of stars. What strange array of chemicals are in the wine? How did they

come to be? There are the ferments, the enzymes, the substrates, and the products. There in wine is

found the great generalization: all life is fermentation. Nobody can discover the chemistry of wine without

discovering, as did Louis Pasteur, the cause of much disease. How vivid is the claret, pressing its

existence into the consciousness that watches it! If our small minds, for some convenience, divide this

glass of wine, this universe, into parts – physics, biology, geology, astronomy, psychology, and so on –

remember that nature does not know it! So let us put it all back together, not forgetting ultimately what it

is for. Let it give us one more final pleasure: drink it and forget it all! ”

Richard Feynman

Epicatechin

TARTARIC ACID (C4H6O6)

2,3-dihydroxybutanedioic acid

Tartaric acid is, from a winemaking

perspective, the most important in wine

due to the prominent role it plays in

maintaining the chemical stability of the

wine and its color and finally in influencing

the taste of the finished wine. [Wikipedia]

MALIC ACID (C4H6O5)

hydroxybutanedioic acid

Malic acid, along with tartaric acid, is one of the

principal organic acids found in wine grapes. In

the grape vine, malic acid is involved in several

processes which are essential for the health

and sustainability of the vine. [Wikipedia]

CITRIC ACID (C6H8O7)

2-hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylic acid

The citric acid most commonly found in wine

is commercially produced acid supplements

derived from fermenting sucrose solutions.

[Wikipedia]

Three primary acids are found in wine grapes:

RESVERATROL DERIVATIVES

trans cis

Malvidin-3-glucoeide

Procyanidin B1 Quercetin

R = H; resueratrol

R = glucose; p Ice Id

TYPICAL WINE FLAVONOIDS

Resveratrol (3,5,4'-trihydroxy-

trans-stilbene) is a stilbenoid,

a type of natural phenol, and

a phytoalexin produced

naturally by several plants.

[Wikipedia]

In red wine, up to 90% of the

wine's phenolic content falls

under the classification of

flavonoids. These phenols,

mainly derived from the

stems, seeds and skins are

often leached out of the

grape during the maceration

period of winemaking. These

compounds contribute to the

astringency, color and

mouthfeel of the wine.

[Wikipedia]

Prolog

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-2-320.jpg)

![2017

MRT

PART V – THE HYDROGEN ATOM

What happens at 10−−−−10 m?

The Hydrogen Atom

Spin-Orbit Coupling

Other Interactions

Magnetic & Electric Fields

Hyperfine Interactions

Multi-Electron Atoms and Molecules

Appendix - Interactions

The Harmonic Oscillator

Electromagnetic Interactions

Quantization of the Radiation Field

Transition Probabilities

Einstein’s Coefficients

Planck’s Law

A Note on Line Broadening

The Photoelectric Effect

Higher Order Electromagnetic Interactions

References

“Quantum field theory is the way it is because […] this is the only way to reconcile the principles of

quantum mechanics […] with those of special relativity. […] The reason that quantum field theory

describes physics at accessible energies is that any relativistic quantum theory will look at sufficiently

low energy like a quantum field theory.” Steven Weinberg, Preface to The Quantum Theory of Fields, Vol. I.

PART III – QUANTUM MECHANICS

Introduction

Symmetries and Probabilities

Angular Momentum

Quantum Behavior

Postulates

Quantum Angular Momentum

Spherical Harmonics

Spin Angular Momentum

Total Angular Momentum

Momentum Coupling

General Propagator

Free Particle Propagator

Wave Packets

Non-Relativistic Particle

Appendix: Why Quantum?

References

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-4-320.jpg)

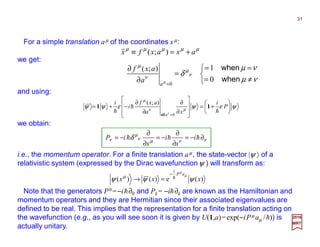

;( θθθθµµµµ

xf

so that the state vector |ψ 〉 will transform according to (i.e., by using Taylor’s expansion):

As an example of symmetry,consideratransformation (parametrizedbythevariableθ,

e.g., an angle ϕ,a translation a or aLorentzboostζ )onthespace-timecoordinates xµ :

in which the real infinitesimal is ε =dθ and the generator for the parameter θ is given by:

∑= =

∂

∂

∂

∂

−=

3

0 0

);(

)(

µ

µ

θ

µ

θ

θ

θ

x

xf

iT

all

ψεεψθψ

θ

θ

θψ

ψ

θ

θ

θψψψψψψ

µµ

µ

µ

θ

µ

µ

µ

µ

µ

θ

µ

µµ

µ

µ

µµµµµ

)]([)()()(

);(

)(

)(

);(

)()()()()(

2

0

0

OTixTdix

x

xf

idix

x

x

xf

dxx

x

dxxxdxx

T

++=+=

∂

∂

∂

∂

−+=

∂

∂

∂

∂

+≡

∂

∂

+≈+=→

∑

∑∑

=

=

111

44444 344444 21

)(Generator

all

all

2017

MRT

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-11-320.jpg)

![with f a(θ ,θ) a function of the θs and θs. Taking θ a =0 as the coordinate of the identity,

we must have:

)),(()()( θθθθ fTTT =

aaa

ff θθθ == ),0()0,(

As mentionned above, the transformation of such continuous groups must be represen-

ted on the physical Hilbert space by unitary operators U[T(θ )]. For a Lie group these op-

erators can be represented by a power series (e.g., in the neighborhoodof the identity):

A finite set of real continuous parameters θ a describe a group of transformations T(θ )

with each element of the group connected to the identity by a path (i.e., UU−1=1) within

the group. The group multiplication law U(T2)U(T1)=U(T2T1) thus takes on the form

(i.e., a connected Lie group):

According to f a(θ ,0)= f a(0 ,θ)=θ a above, the expansion of f a(θ ,θ) to second-order must

take the form:

2017

MRT

K+++= ∑∑∑ c b

bc

cb

a

a

a

TTiTU θθθθ

2

1

)]([ 1

where Ta, Tbc =Tcb, &c. are Hermitian operators independent of the θ s. Suppose that the

U[T(θ )] form an ordinary (i.e., φ =0) representation of this group of transformations, i.e.:

))],(([)]([)]([ θθθθ fTUTUTU =

...),( +⊕+= ∑∑c b

cba

bc

aaa

ff θθθθθθ

with real coefficients f a

bc. The addition of the second-order term is emphasized by ⊕.

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-12-320.jpg)

![(The Σ were also omitted to get space.) The terms of order 1, θ, θ, and θ 2 automatically

match on both sides of this equation – from the θ θ terms we get a non-trivial condition:

KKKK ++++++++=+++×+++ bc

ccbb

a

cba

bc

aa

bc

cb

a

a

bc

cb

a

a

TTfiTTitti ))(()(][][ 2

1

2

1

2

1 θθθθθθθθθθθθθθ 111

∑−−=

a

a

a

bccbbc TfiTTT

Since we are following Weinberg’s development, he points out that: This shows that if

we are given the structure of the group, i.e., the function f a(θ,θ ), and hence its quadratic

coefficient f a

bc, we can calculate the second-order terms (i.e., Tbc) in U[T(θ)] from the

generators Ta appearing in the first-order terms. (A pretty amazing fact wouldn’t you say?)

Applying the multiplication rule U[T(θ)]U[T(θ)]=U[T( f (θ ,θ )] and using the series

U[T(θ)]=1+iθ a Ta +½θ bθ c Tbc +…above withθ → f a (θ,θ)=θ a +θ a + f a

bc θ b θ c ,we get:

where Ca

bc are a set of real constants known as structure constants:

∑=−≡

a

a

a

bcbccbcb TCiTTTTTT ],[

2017

MRT

However, as he points out: There is a consistency condition: the operator Tbc, must be

symmetricinbandc(becauseitisthesecondderivativeof U[T(θ)]withrespect toθ b andθ c)

so the equation Tbc =−Tb Tc −iΣa f a

bc Ta above requires that the commutation relations be:

a

cb

a

bc

a

bc ffC +−=

Such a set of commutation relations is known as a Lie algebra to mathematicians.

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-13-320.jpg)

![This is the case for instance for ‘translations’ in spacetime, or for ‘rotations’ about any

one fixed axis(though not both together).Then the coefficients f a

bc in the function f a(θ,θ )

=θ a +θ a +Σbc f a

bc θ b θ c vanish,and so do the structure constants Ca

bc=− f a

bc+ f a

cb, that is

Ca

bc =0. So, [Tb ,Tc]≡TbTc −TcTb reduces to the fact that the generators then all commute:

aaa

f θθθθ +=),(

N

N

TUTU

=

θ

θ)]([

Such a group is called Abelian. In this case, it is easy to calculate U[T(θ)] for all θ a.

Again, from the group multiplication rule U[T(θ)]U[T(θ)]=U[T( f (θ ,θ ))] and the function

f a(θ,θ)= θ a +θ a above, and taking ε=θ/N, we have for any integer N:

As a special case of importance, suppose that the function f a(θ,θ) is simply additive:

and hence:

0],[ =cb TT

2017

MRT

Letting N→∞, and keeping only the first-order term in U[T(θ /N)], we have then:

N

a

a

a

N

T

N

iTU

+= ∑∞→

θ

θ 1lim)]([

TiTi

UTU a a

a

θθ

θθ e)(e)]([ =⇒=

∑

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-14-320.jpg)

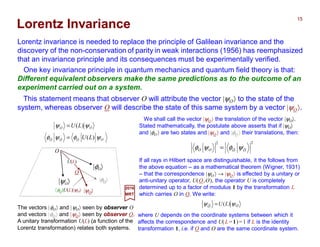

![The Relativity Principle

Einstein’s principle of relativity states the equivalence of certain ‘inertial’ frames of

reference. It is distinguished from the Galilean principle of relativity, obeyed by

Newtonian mechanics, by the transformation connecting coordinate systems in different

inertial frames.

2017

MRT

Here ηµν is the diagonal 4×4 matrix, with elements (i.e., the Minkowski metric): η00 =+1,

η11 =η22 =η33 =−1 and ηµν ≡0 for µ ≠ν. These transformations have the special property

that the speed of light c is the same in all inertial frames (e.g., a light wave traveling at

speed c satisfies |dr/dt|=c or in other words Σµνηµν dxµ dxν =c2dt2 − dr2 =0, from which it

follows that Σµνηµν dxµ dxν =0, and hence |dr /dt|=c).

If the contravariant vector xµ =(ct,r) are the coordinates in one inertial frame (x1, x2, x3)

[i.e., r = xi (i=1,2,3), as Cartesian space coordinates, and x0 =ct a time coordinate, the

speed of light being c] then in any other inertial frame, the coordinates xµ must satisfy:

OO

xdxdxdxd

FrameFrame

∑∑∑∑ = == =

≡

3

0

3

0

3

0

3

0 µ ν

νµ

µν

µ ν

νµ

µν ηη

or equivalently stated as the Principle of covariance:

∑∑ ∂

∂

∂

∂

=

µ ν

µνσ

µ

ρ

µ

σρ ηη

x

x

x

x

The covariant vector can be given as xµ=Σνηµν xν =(ct,−r). The norm of the vector

Σµ xµ xµ =(x0)−Σi(xi)2 =c2t2 −|r|2 is a Lorentz invariant term.

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-17-320.jpg)

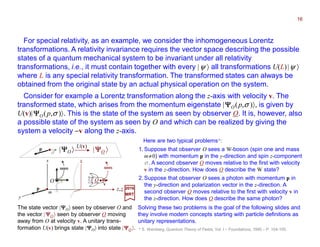

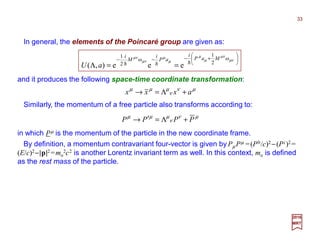

![Poincaré Transformations

with aµ arbitraryconstants(e.g.,‘leaps’),and Λµ

ν aconstantmatrixsatisfyingthecondition:

Any coordinate transformation xµ → xµ that satisfies Σµνηµν (∂xµ /∂xρ )(∂xν /∂xσ )=ηρσ is

linear and allows us to define the Poincaré Transformations:

2017

MRT

µµµµµµ

ν

ν

ν

µµ

axxxxaxx +Λ+Λ+Λ+Λ=+Λ= ∑=

3

3

2

2

1

1

0

0

3

0

σρ

µ ν

σ

ν

ρ

µ

µν ηη =ΛΛ∑∑

The matrix ηµν has an inverse, written ηµν , which happens to have the same

components: it is also diagonal matrix, with elements: η00 =+1,η11 =η22 =η33 =−1 and

ηµν ≡0 for µ ≠ν.

To save on using summation signs (Σ), we introduce the Summation Convention:

We sum over any space-time index like µ and ν (or i, j or k in three dimensions) which

appears twice in the same term, if they appear only once ‘up’ and also only once ‘down’.

As an example, and while also enforcing this tricky summation convention, we now

multiply ηµµµµνννν Λµµµµ

ρ Λνννν

σ=ηρσ above with ησττττΛκ

ττττ and when inserting parentheses for show:

ρ

κ

ρ

κκ

ρ

κ

ρ

κ

ρ

κ

ρ ηηηηηηηηη µµµµνννν

µνµνµνµν

σσσσ

σσσσ

ττττσσσσ

ττττσσσσ

ττττσσσσ

ττττσσσσ

ννννµµµµ

µνµνµνµν

µνµνµνµν ττττσσσσ

ττττσσσσ

ττττσσσσ

ννννµµµµ

µνµνµνµν Λ=Λ=Λ=Λ=ΛΛΛ=ΛΛΛ∑ ∑ ][)(])[(])[(

44 34421

and now, when multiplying with the inverse of the matrix ηµµµµν Λµµµµ

ρ, we get from this:

ττττσσσσ

ττττσσσσ ηη κνκν

ΛΛ=

( )3,2,1,0=µ

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-18-320.jpg)

![and this unitary operator U satisfies the same group composition rule as T(Λ,a):

So, in accordance with the discussion in the previous slides, the transformations T(Λ,a)

induced a unitary linear transformation on a state vector in the Hilbert space:

For example, we will soon discuss the wave function in its momentum representation:

for which the same composition rule applies:

2017

MRT

)]()([)]([)]([),( 1

pLpLUpLUpLUpU ΛΛΛ=Λ≡Λ −

),(),(),(),;( jjj mppUmpmjp ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ Λ=→µ

)(),()()( xaUxx ψψψ µ

Λ=→

),(),(),( aaUaUaU +ΛΛΛ=ΛΛ

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-20-320.jpg)

![Now it is time to study three-dimensional rotations and add relativity to the overall

description. To this effect we will exploit pretty much all the group symmetry properties!

2017

MRT

ζζβγ

ζζβγ

sinhcosh)(

sinhcosh)(

03033

22

11

30300

xxxxx

xx

xx

xxxxx

−=−=

=

=

−=−=

and v=|v| is the relative velocity of the two frames.

or (N.B., implicit sum on ν ):

β

ζ

ζ

ζβγβζ

β

ζγ ==

==

−

==

cosh

sinh

tanhsinh

1

1

cosh

2

aswellaswithand

c

v

−

−

=

3

2

1

0

3

2

1

0

cosh00sinh

0100

0010

sinh00cosh

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

ζζ

ζζ

that is, assuming propagation in the direction of the x3-axis. This can be represented in

matrix form as:

Let us recall a few facts about homogeneous Lorentz transformations:

where:

ν

ν

µνµµ

ζ xxxx )],-([Λ=

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-21-320.jpg)

![The explicit matrix representation of a restricted homogeneous Lorentz transformation

in the x1-direction (i.e., a rotation in the x0-x1 plane) is given by:

Similarly, the infinitesimal generators M02 and M03 for rotations in the x0-x2 and x0-x3

planes respectively, are given by:

and the infinitesimal generator M10 for this rotation is defined as:

−

−

=

1000

0100

00coshsinh

00sinhcosh

)(Λ[01] ζζ

ζζ

ζ

==≡

=

0000

0000

0001

0010

)(Λ

0

[01]

10

1

ζ

ζ

ζ

d

d

MK

==≡

==≡

==

0001

0000

0000

1000

)(Λ

0000

0001

0000

0100

)(Λ

0

[03]

03

3

0

[02]

02

2

ζζ

ζ

ζ

ζ

ζ

d

d

MK

d

d

MK ,

2017

MRT

22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-22-320.jpg)

![A finite rotation in the µ -ν plane (in the sense µ toν ), is again obtained by

exponentiation:

2017

MRT

ζνµ µν

ζ M

xx e),-(Λ =

µσνρνρµσµρνσνσµρρσµν

ηηηη MMMMMM −−+=],[

One verifies that the infinitesimal generators, Mµν ,satisfy the following commutation

rules:

25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-25-320.jpg)

![

∂

∂

=

∂

∂

−=

∂

∂

−=

∂

∂

∂

∂

−=•

=

kj

kji

ikji

kji

k

k

k

x

xi

x

xi

x

i

x

xf

i

εε

ζ

ζ

ϕ

µ

)ˆ()ˆ()ˆ(

);(ˆˆ

0

nnrn

Jn

××××

hence:

kj

kjii

x

xiJ

∂

∂

= ε

For the rotation acting on the space-time coordinates, note that the time coordinate is

unaffected (hence only latin indices):

•−=

−•−+=

=

+−+==≡

ζζ

ζζ

ϕϕϕϕµµ

sinhˆcosh

]sinhˆ)1[(coshˆ

]ˆ[sin)]ˆ(ˆ)[cos1()],ˆ([);(

rn

nrnrr

rnrnnn

cttc

ct

xxRxfx kkki

i

k

××××××××××××

in which we made use of the relation xj =ηij xj =−x j, η being the Minkowski 3-metric. It can

be shown that the generators for rotation are equivalent to the generators for the SO(3)

Special Orthogonal group (which are Hermitian). Thus, the representation for a finite

rotation acting on the wavefunction is unitary and it is given by U(R)=exp(−iϕ n•J/h).ˆ

2017

MRT

where v=ctanhζ n. So, we get:ˆ

26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-26-320.jpg)

(

ˆ j

iR

R ϕ

ν

µ

n

2017

MRT

27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-27-320.jpg)

;(

x

x

x

xi

x

x

x

xi

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

xi

x

xi

x

xf

iK

ζζζζ

µ

ν

ζ

ν

µ

µ

ζ

µ

ζζζζ

ζζ

ζ

2017

MRT

28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-28-320.jpg)

![Similarly:

)( 0000 iiiii xxi

x

x

x

xiK ∂−∂=

∂

∂

−

∂

∂

=

†

00

])([)()()( xKx

x

xx

x

xixK iiii ψψψψ ≠

∂

∂

−

∂

∂

=

Consider that the state-vector of the system is given by |ψ 〉, hence the action of Ki on

the state is:

This implies that the generator for the Lorentz boost, Ki, is not Hermitian and hence the

exponentiation of the generator (i.e., exp(−iζ i Ki /h)) will not be unitary. The

representation of the Lorentz boost acting on the wavefunction is not unitary and hence

is not trace-preserving.

We can summarize the effects of the rotations and the Lorentz boost into one second-

rank covariant tensor:

)( µννµµν ∂−∂= xxiM

in which Ji =½ε ijk Mjk and Ki =Mi0.

2017

MRT

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-29-320.jpg)

![These generators (i.e., Pµ and Mµν ) obey the following commutation relations, which

characterize the Lie algebra of the Poincaré group (and adding h and c for reference):

kkjijikkjijikkjiji JiKKKiKJJiJJ εεε hhh −=== ],[],[],[ and;

0],[

)(],[

)(],[

=

−−=

−+−−=

λµ

νµλµνλλµν

νρµσµρνσµσνρνσµρµνρσ

ηη

ηηηη

PP

PPiPM

MMMMiMM

h

h

The rotation Ji and boost Kj generators can be written in covariant notation Mµν and

the commutation relations are then re-written as:

2017

MRT

00

],[],[],[ P

c

iPKcPiPKPiPJ jijiiikkjiji δε

h

hh === and;

0],[0],[0],[ 00

=== jiii PPPPPJ and;

The first of these is the usual set of commutators for angular momentum, the second

says that the boost K transforms as a three-vector under rotations, and the third implies

that a series of boosts can be equivalent to a rotation. Next we have:

where P0c=H, the Hamiltonian, and finally all components of Pµ should commute with

each other:

Together, these equations above form the Lie algebra of the Poincaré group.

30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-30-320.jpg)

![]ω,ω)([

]ω)(,ω)([

]ω)(,ω)([

]ω)(,ω)[(),(

])ω)((,ω)[(),(),(),ω(),(),(),ω(),(

11

111

11

ω)(ω)(

11

11

ω

111

11

11

aU

aaaU

aaU

aUaU

aUaUaUUaUaUUaU

aaaa

aaa

−−

−−−

−−

+Λ+−=Λ+=Λ=Λ=Λ

−−

−−

Λ−=Λ=Λ=+=Λ

−−−

ΛΛ−ΛΛ+Λ≡

ΛΛ+Λ+ΛΛ−Λ+Λ=

+Λ+Λ+Λ−Λ+Λ=

+Λ+−Λ+Λ=

+Λ−+Λ+Λ=Λ−Λ+Λ=Λ+Λ

−−

−−

ε

ε

ε

ε

εεε

ε

ε

1

1

11

11

1111

11

1

4444444 34444444 21

4444 34444 21

&;;

&;;

2017

MRT

where Λµ

ν and aµ are here the parameters of a new transformation, unrelated to ω and

ε.

Let us consider the Lorentz transformation properties of Pρ and Mρσ. We consider the

product:

),(),( 1

aUaU Λ+Λ −

),(1 εεεεωωωωU

In the end the transformation rule is given by:

],[),(),(),( 111

aUaUUaU −−−

ΛΛ−ΛΛΛ+≡Λ+Λ ωωωωωωωωωωωω εεεεεεεε 11

since Λ1Λ−1= 1.

According to the composition rule T(Λ,a)T(Λ,a)= T(ΛΛ,Λa+a) with T =U(Λ,a) the

product U(Λ−1,−Λ−1a) U(Λ,a) equals U(1,0), so U(Λ−1,−Λ−1a) = U−1(Λ,a), i.e., U(Λ−1,−Λ−1a)

is the inverse of U(Λ,a). It follows from U(Λ,a)U(Λ,a)= U(ΛΛ,Λa+a) that, in sufficient

detail to show these important group operations so that they be well understood, we have:

36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-36-320.jpg)

![2017

MRT

Using U(1+ω,ε)=1−(i/h)ερ Pρ +½(i/h)ωρσ Mρσ to first order in ω and ε we have then:

)(ω

2

1

)(

2

1

)(

2

1

ω

ω

2

1

)(ω

2

1

])(ω[

)ω(

2

1

)ω(),(ω

2

1

),(

1

1

111

µννµµνσ

ν

ρ

µρσ

µρ

µρ

µννµνµµνσ

ν

ρ

µρσ

µρ

µρ

µνσ

ν

ρ

µρσ

µν

ν

σ

ρσ

ρ

µ

µν

ν

σ

ρσ

ρ

µ

µ

ρ

ρ

µ

µν

µν

µ

µ

σρ

σρ

ρ

ρ

ε

ε

ε

εε

PaPaM

i

P

i

PaPaPaPa

i

P

i

M

i

M

i

PaP

i

M

i

Pa

i

aUM

i

P

i

aU

−−ΛΛ+Λ−=

++−ΛΛ+

Λ−

ΛΛ+=

ΛΛ+

ΛΛ−Λ−=

ΛΛ+ΛΛ−Λ−=Λ

+−Λ

−

−

−−−

hh

h

h

h

h

h

hhhh

1

1

1

11

Equating coefficients of ωρσ and ερ on both sides of this equation we find:

)(),(),(

),(),(

1

1

µννµµνσ

ν

ρ

µ

σρ

µρ

µ

ρ

PaPaMaUMaU

PaUPaU

−−ΛΛ=ΛΛ

Λ=ΛΛ

−

−

where we have exploited the antisymmetry of ωρσ , i.e., ωρσ =−ωσρ , and we have used

the inverse (Λ−1)ν

σ =Λν

ρ =ηνµ ηρσ Λµ

ρ.

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-37-320.jpg)

![Next, let’s apply these rules rules to a transformation that is itself infinitesimal, i.e.,

Λµ

ν=δ µ

ν +ωµ

ν and aµ =ε µ, with infinitesimals ωµ

ν andεµ unrelated to the previous ω

and ε.

2017

MRT

Equating coefficients of ωρσ and ερ on both sides of these equations, we would find

these commutation rules:

µρνσρνµσσνρµµσρνρσµν

ρσµσρµρσµ

ρµ

ηηηη

ηη

MMMMMM

i

PPMP

i

PP

+−+=

−=

=

],[

],[

0],[

h

h

This is the Lie algebra of the Poincaré group.

µρ

µ

ρµ

µ

µν

µν ε PPPM

i

ω,ω

2

1

=

−

h

νρσ

ν

µσρ

µ

ρσσρµνµ

µ

µν

µν εεε MMPPMPM

i

ωω,ω

2

1

+++−=

−

h

and

By using U(1+ω,ε)=1−(i/h)ερ Pρ +½(i/h)ωρσ Mρσ and keeping only terms of first order

in ωµ

ν andε µ, our equations for Pρ and Mρσ become:

38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-38-320.jpg)

![In quantum mechanics a special role is played by those operators that are conserved,

i.e., that commute with the energy operator H=P0. We just saw that [Pµ,Pρ]=0 and

(i/h)[Pµ,Mρσ ]=ηµρPσ−ηµσ Pρ shows that these are the momentum three-vectors:

2017

MRT

and the angular momentum three-vector:

These are not conserved, which is why we do not use the eigenvalues of K to label

physical states. In a three-dimensional notation, the commutation relations may be

written:

where i, j, k, &c. run over the values 1, 2, and 3, and εijk is the totally antisymmetric

quantity with ε123 =+1. The commutation relation [Ji ,Jj ]=iεijk Jk is the angular-

momentum operator.

],,[ 321

PPP=P

],,[],,[ 211332123123

JJJJJJ −−−==J

and the energy P0 itself. The remaining generators form what is called the ‘boost’ three-

vector:

],,[],,[ 030201302010

JJJJJJ −−−==K

jijikjkiji

kjkijikjkijikjkiji

iiii

HiPKPiPJ

JiKKKiKJJiJJ

PiHKHHHPHJ

δε

εεε

==

−===

====

],[],[

],[],[],[

],[0],[],[],[

and

and,

and

39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-39-320.jpg)

![Now,* there is one peculiar consequence to one of these commutators – the two boost

generators are:

2017

MRT

This commutator means that two boosts, Bi and Bj , in different directions (i.e., the

indices i and j can’t equal each other at the same time) are not equivalent to a single

boost B:

where B is some boost. The reason things aren’t equal is the factor Wn××××m(Ω), the Wigner

Rotation where Ω is the Wigner Angle (i.e., a true space-time rotation although to be

realistic, for practical reason it is usually an infinitesimal one.)

BWBB )(ˆˆˆˆ Ω= mnmn ××××

kjkiji JiKK ε−=],[

)()()()( ˆˆˆˆ

1

ˆˆˆˆˆˆ Ω=ΩΩΩ= −

mnmnmnmnmn ×××××××××××××××× WBWBWWBB

* Credit for developing this in the way it is shown here (and in the next few slides), with an example of which is given pretty

much as it is, is much due to Entanglement in Relativistic Quantum Mechanics, E. Yakaboylu, arxiv:1005.0846v2, August 2010.

By using B=WBW−1, the expression Bn Bm =Wn××××m (Ω)B above can be re-written as:ˆ

ˆ ˆ

ˆ ˆ ˆ

40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-40-320.jpg)

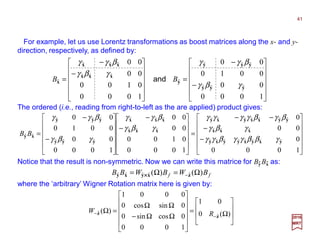

![By replacing sinΩ and cosΩ in the boost matrix Bf one gets:

2017

MRT

Notice now that this Bf matrix is symmetric. So, as a result in this case (i.e., a boost

along the x-direction followed by a boost in the y-direction), we obtain a boost along

‘some’ direction given by Ω=tan−1[− βxγx βyγ y /(γx+γy)] in the x-y plane.

+

+

+

−

++

+−

−−

=Ω= −

−

1000

0

1

)(

1

0

11

1

0

)(

ˆˆ

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆ

2

ˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆ

ˆˆ

2

ˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆ

2

ˆ

2

ˆ

2

ˆ

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆ

1

ˆ

yx

yxy

yx

yyxx

yy

xy

yyxx

yx

yxx

yxx

yyyxxyx

xyz

γγ

γγγ

γγ

γβγβ

βγ

γγ

γβγβ

γγ

γβγ

γβγ

βγγβγγγ

BBWBf

mnmn ˆˆ

1

ˆˆ )( BBWB Ω= −

××××

Note that we can read BnBm =Wn××××m (Ω)Bf (e.g., By Bx =Wy××××x (Ω)Bf =W−z (Ω)Bf in the

example above) backward to note that any boost B in the n-m (e.g., the x-y plane in the

example above) can be decomposed into two mutually perpendicular boosts (in order)

followed by a Wigner rotation (using group algebra – we mean it’s inverse)*:

ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ

ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ

* Credit for this notation is based on Generic composition of boosts: An elementary derivation of the Wigner rotation, R.

Ferraro and M. Thibeault, Eur. J. Phys. 20 (1999) 143-151.

This result will be used later when we discuss particle representation in quantum field

theory using Wigner basis states and especially when we calculate one first hand…

ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ

43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-43-320.jpg)

![Since we will be using this soon let us look at a general example. Suppose that a parti-

cle of mass mo is seen from system O with momentum p along the +z-axis. A second ob-

server sees the same particle from a system O moving with velocity v along the +x-axis:

ΩΩ

Ω−Ω−Ω+Ω−−

Ω+ΩΩ−Ω

=

ΩΩ

Ω−Ω

ΩΩ

−

−

=

ΩΩ

Ω−Ω

+

+

−

−

=ΛΛ=Λ −

−−=

cos0sin

0100

sincos0cossin

sincos0cossin

cos0sin

0100

sin0cos0

cos0sin

1000

0100

00

00

cos0sin0

0100

sin0cos0

0001

00

0100

0010

00

1000

0100

00

00

),()()(

ˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆ

1

ˆˆˆˆˆˆ

zzzz

xzzxxxzzxxzxx

xxzzxxxzzxzx

zzzz

zzzzz

xxx

xxx

zzz

zzz

xxx

xxx

yzxyzx

γγγβ

γγβγβγγβγβγγβ

γβγβγγβγβγγγ

γγγβ

γβγβγ

γγβ

γβγ

γγβ

γβγ

γγβ

γβγ

pWpLpL ××××

2017

MRT

+

−=Ω⇒

+

−=Ω=

Ω

Ω

Ω=Ω+−⇒Ω=Ω−Ω−

zx

zzxx

zx

zzxx

zzxxzxzxzzxx

ˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆ

arctantan

cos

sin

cossin)(sinsincos

γγ

γβγβ

γγ

γβγβ

γβγβγγγγγβγβ

Since Lx××××z(Λp) is symmetric we can extract the [Lx××××z(Λp)]3

2=[Lx××××z(Λp)]2

3 components:ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ ˆ

44](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-44-320.jpg)

![px

W−−−−y(Λ,p)

Now, since:

This provides us with the three Cartesian values for the boosted

momentum:

2017

MRT

y

mo

Suppose that observer O sees a particle

(mass mo ≠0) with momentum pz in the z-

direction. A second observer O moves relative

to the first with velocity v in the x-direction.

How does O describe the particle’s motion?

Λp

)ˆˆ(ˆˆ ˆˆˆˆˆoˆˆ kikip zzzxxzx γβγγβ +−=+−=Λ cmpp

pz

Λ(v)

y

x

v ↑

−−

−

=

−

−

=Λ

zzz

zzxxxzxx

zzxxxzx

zzz

zzz

xxx

xxx

zx

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆ

00

0100

0

0

00

0100

0010

00

1000

0100

00

00

)(

γγβ

γβγβγγγβ

γβγγβγγ

γγβ

γβγ

γγβ

γβγ

pL

−

=

−−

−

=Λ

cm

cm

cmcm

kpL

oˆˆ

oˆˆˆ

oˆˆo

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆˆˆˆ

ˆˆ

0

0

0

0

00

0100

0

0

)(

zz

zxx

zx

zzz

zzxxxzxx

zzxxxzx

zx

γβ

γγβ

γγ

γγβ

γβγβγγγβ

γβγγβγγ

µ

we then have (N.B., with kµ=[moc,0,0,0]T a standard rest momentum for massive particles):

−

=

Λ

Λ

Λ

zz

zxx

ˆˆo

ˆˆˆo

3

2

1

0

γβ

γγβ

cm

cm

p

p

p

)ˆˆ(ˆˆ ˆˆˆˆˆooˆˆoˆˆˆ kikip zzzxxzzzxx γβγγβγβγγβ +−=+−=Λ cmcmcm

x

z

z

Lz(p)

which when applied in the Figure will look like:

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-45-320.jpg)

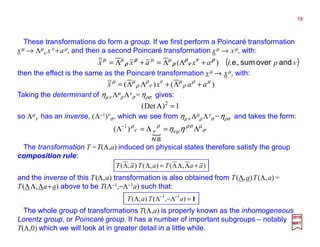

![The Poincaré Algebra

and is a space-time translation, i.e., as the product operation of a translation by a real

vector aµ =[τ,a] and a homogeneous Lorentz transformation, Λµ

ν (the translation being

performed after the homogeneous Lorentz transformation.) It can conveniently be

represented by the following matrix equation:

The inhomogeneous Lorentz transformation (or Poincaré group), L={Λ,a}, is defined by:

2017

MRT

ΛΛΛΛ

ΛΛΛΛ

ΛΛΛΛ

ΛΛΛΛ

=

1100001

3

2

1

0

33

3

3

2

3

1

3

0

22

3

2

2

2

1

2

0

11

3

1

2

1

1

1

0

00

3

0

2

0

1

0

0

3

2

1

0

x

x

x

x

a

a

a

a

x

x

x

x

The commutation rules of these generators with themselves are the Poincaré Algebra:

µν

ν

µµµ

axx +Λ== )( xL

ρµσνρνσµµσµρµσνρρσµνρµ

ηηηη MMMMMMiPP +−−== ],[0],[ and

ρµσσµρσρµ

ηη PPMPi −=],[

where the last coordinate, i.e., 1, has no physical significance and is left invariant by the

transformation. The generators for infinitesimal translations are the Hermitian operators

Pµ, and their commutative relations with the Hermitian generators for ‘rotations’ in the

xµ -xν plane, Mµν =−Mν µ are as expressed in contravariant form:

46](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-46-320.jpg)

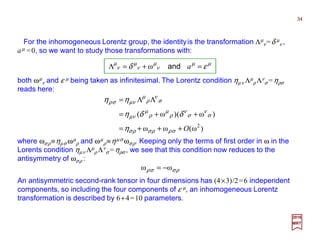

![Lorentz Transformations

We note from (detΛ)2=1 above that either detΛ=+1 or detΛ=−1; those transformations

with detΛ=+1 form a subgroup of either the homogeneous or the inhomogeneous

Lorentz group. Furthermore, from the 00-components of ηµν Λµ

ρ Λν

σ=ηρσ and Λν

σ Λκ

τ ηστ

=ηνκ, we have:

These transformations also form a group.

Now, those transformations with aµ =0 form a subgroup with to the Poincaré group:

with i summed over the values 1, 2, and 3. We see that either Λ0

0≥+1 or Λ0

0≤−1. Those

transformations with Λ0

0≥+1 form a subgroup. Note that if Λµ

ν and Λµ

ν are two such Λs,

then:

ii

ii 00

00

2

0

0

11)( ΛΛ+=ΛΛ+=Λ

0

3

3

0

0

2

2

0

0

1

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

)( ΛΛ+ΛΛ+ΛΛ+ΛΛ=ΛΛ≡ΛΛ µ

µ

)0,()0,()0,( ΛΛ=ΛΛ TTT

2017

MRT

Taking the determinant of ηµν Λµ

ρ Λν

σ=ηρσ gives:

so Λµ

ν has an inverse, [Λ−1]ν

σ, which we see from ηµν Λµ

ρ Λν

σ=ηρσ and takes the form:

σ

µσρ

µν

ρ

νν

ρ

ηη Λ=Λ=Λ−

][ 1

These transformations also form a group. known as the homogeneous Lorentz group.

If we first perform a Lorentz transformation Λ:

ν

ν

ρ

ρ

µρ

ρ

µµ

xxx ΛΛ=Λ=

1)det( 2

=Λ

47](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-47-320.jpg)

![and so:

The subgroup of Lorentz transformations with detΛ=+1 and Λ0

0≥+1 is known as the

proper orthochronous Lorentz group.

1)(1)( 2

0

02

0

0

0

3

3

0

0

2

2

0

0

1

1

0

0

0

−Λ−Λ≤ΛΛ+ΛΛ+ΛΛ≡ΛΛ i

i

But (Λ0

0)2=1+Λi

0Λi

0=1+Λ0

iΛ0

i shows that the three-vector [Λ1

0,Λ2

0,Λ3

0] has length

√[(Λ0

0)2−1], and similarly the three-vector [Λ0

1,Λ0

2,Λ0

3] has length √[(Λ0

0)2−1], so the

scalar product of these two three-vector is bounded by:

1)(1)()( 2

0

02

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

−Λ−Λ−ΛΛ≥ΛΛ

2017

MRT

49

If we look over the Lorentz transformation properties of Pρ and Mρσ is the case for

homogeneous Lorentz transformations (i.e., aµ =0), we get:

µνσ

ν

ρ

µ

σρ

µρ

µ

ρ

MaUMaU

PaUPaU

ΛΛ=ΛΛ

Λ=ΛΛ

−

−

),(),(

),(),(

1

1

These transformation rules simply say that Mρσ is a tensor and Pρ is a vector. For pure

translations (i.e., with Λµ

ν =δ µ

ν ), they tell us that Pρ is translation-invariant, but Mρσ is

not.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-49-320.jpg)

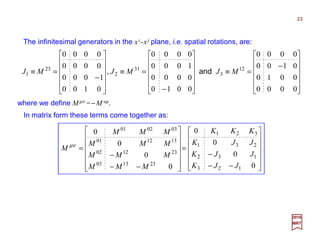

![The problem of finding the representation of the ‘restricted’ Lorentz group is equivalent

to finding all the representations of the commutation rules above. The finite dimensional

irreducible representation of the restricted group can be labeled by two discrete indices

which can take on a values the positive integers, the positive half-integers, and zero. To

show this, let us define the operators:

2017

MRT

and their commutation rules are:

From these operators, we can construct these invariants of the group:

( )

( )

( )Boost

momentumAngular

Momentum

],,[

],,[

],,[

030201

211323

321

MMM

MMM

PPP

=

=

=

K

J

P

kijkji

kijkji

kijkji

KKJ

JKK

JJJ

ε

ε

ε

=

−=

=

],[

],[

],[

which commute with all the Ji and Ki. They are therefore the invariants of the group and

they are multiples of the identity in anyirreduciblerepresentation.The representations

can thus be labeled by the values of these operators in the given representation.

and

µν

µν MM2

122

=− KJ

ρσµν

µνρσε MM8

1=•− KJ

51](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-51-320.jpg)

![which satisfy the following commutation rules:

To make the range of values of the label more transparent, let us introduce the

following generators:

2017

MRT

)(

2

1

)(

2

1

iiiiii KiJiKKiJiJ −=+= and

and

It follows from the commutation rules that a finite dimensional irreducible

representation space, Vjj' can be spanned by a set of (2j +1)(2j' +1) basis vectors

| jmj, j'm'j〉 where j, mj, j' and m'j are integers or half-odd integers, −j ≤ mj ≤ j, −j' ≤ m'j ≤ j'

and in terms of which the J and K operators have the following representation:

0],[

],[

],[

=

=

=

ji

kijkji

kijkji

KJ

JiKK

JiJJ

ε

ε

jjjjj

jjjjjjjj

mjmjmmjmjJ

mjmjmjmjmjmjJiJmjmjJ

′′=′′

′′±+±=′′±=′′±

,;,,;,

,;1,)1)((,;,)(,;,

3

21

h

hm

jjjjj

jjjjjjjj

mjmjmmjmjK

mjmjmjmjmjmjKiKmjmjK

′′′=′′

±′′+′±′′′=′′±=′′±

,;,,;,

1,;,)1)((,;,)(,;,

3

21

h

hm

53](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-53-320.jpg)

![One-Particle States

The physical states of particles are described by the Wigner basis states |ΨΨΨΨkmo

( j,mj)〉

(which are equivalent to the states|ΨΨΨΨ(k,mj)〉) for a unitary irreducible representation

of the inhomogeneous Lorentz group (Poincaré group) with Σµ pµ p µ =p02

−p2 =(moc)2.

Thesestatesformthe Hilbert space of the theory and the momentum states |ΨΨΨΨ(p,mj)〉 can

be obtained from the standard state |ΨΨΨΨpmo

( j,mj)〉≡|ΨΨΨΨ( p,mj)〉 by a unitary transformation:

∑

+

−=′

Λ

′−•−

′Λ

Λ

=≡

j

jm

jEp

m

m

j

tE

i

j

j

j

mjpW

pE

pE

xx ),()],([e

)(

)(

)π2(

1

)()( )(

)(

2/3

ΨΨΨΨD

rp

h

h

ψψ µ

Our goal is to find eigenkets of |ΨΨΨΨpmo

( j,mj)〉 as they appear following an homogeneous

Lorentz transformation group U(ΛΛΛΛ,a) product on a state-vector |ΨΨΨΨpmo

( j,mj)〉 is as follows:

where L( p) is some standard Lorentz transformationmatrix that depends on p=pµ and the

momentum states are normalized over intermediate states andweget the coordinate ket:

),()(),( jj mkpLmp ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ =

),()]([)]([)]([)]([

)(

),(

),()]([)]([

)(

),(),(),(

o

oo

1o

o

jmk

jmkjmp

mjpUpLUUpLU

pE

m

aU

mjpUU

pE

m

aUmjaU

ΨΨΨΨ

ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ

LvΛ1

LvΛ1Λ

ΛΛ=

=

−

2017

MRT

The spin j corresponds to the eigenvaluesJ2= j( j +1)h2of J2 and J3 =mj h (mj = j, j −1,…,−j).

Also, U(1,a)|ΨΨΨΨkmo

( j,mj)〉 meansthesamethingas exp(−iΣµ kµ aµ)|ΨΨΨΨkmo

( j,mj)〉(pµ =hkµ ).

57](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-57-320.jpg)

![The Lorentz transformations associated with the Poincaré group can be constructed in

which the quantum state differs by only a mixture of the internal spin indices mj (i.e., run-

ning over the discrete values j, j −1,…,−j) but possess the same physical observables.

The effects of the inhomogeneous Lorentz transformations (e.g., acting on the Dirac

fields) can be elucidated by considering the particle states obtained from the irreducible

unitary representations of the Poincaré group. The unitary operation representing the

Lorentz transformations acting on the Poincaré generators are given by the equations

U(Λ,a)PρU−1(Λ,a)=Σµ[Λ−1]ρ

µPµ & U(Λ,a)MρσU−1(Λ,a)=Σµν [Λ−1]ρ

µ [Λ−1]σ

ν (Mµν−aµ Pν −aν Pµ).

Since the momentum four-vector commutes among each other according to [Pµ ,Pν]=0,

the particle states can be characterized by the four-momentum Pµ together with

additional internal degrees of freedom mj. The internal degrees of freedom pertain to the

spin vector which can be affected by transformations in the space-time coordinates.

and the state transforms accordingly for a space-time translation:

),(),( jj mppmpP ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ µµ

=

),(e),(e),(),( j

ap

i

j

aP

i

j mpmpmpaU ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ

∑∑ −−

=≡ µ µ

µ

µ µ

µ

hh1

Thus, the one-particle state is an eigenvector of the momentum operator:

2017

MRT

The components of the energy-momentumfour-vector operator Pµ all commute with each

other (i.e., [Pµ,Pν ]=0), so it is natural to express physical state-vectors in terms of

eigenvectors of the four-momentum.This four-momentum Pµ is a trusted observable!

58](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-58-320.jpg)

![Under space-time translations, the states |ΨΨΨΨ(p,mj)〉 transforms as:

2017

MRT

It is thus natural to identify the states of a specific particle type with the components

of a representation of the inhomogeneous Lorentz group which is irreducible.

Hence U(ΛΛΛΛ)|ΨΨΨΨ(p,mj)〉 must be a linear combination of the state vectors |ΨΨΨΨ(Λp,mj)〉:

We must now consider how these states transform under homogeneous Lorentz

transformations U(ΛΛΛΛ,0)≡U(ΛΛΛΛ) is to produce eigenvectors of the four-momentum with

eigenvalues Λp (where we use U −1 (ΛΛΛΛ,a)Pµ U(ΛΛΛΛ,a)=Σν [Λ−1]µ

ν Pν ):

),()()(),()(

),(][)(),()]()([)(),()( 11

jj

jjj

mpUpmpUp

mpPUmpUPUUmpUP

ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ

ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ

ΛΛ

ΛΛΛΛΛ

µ

ν

ν

ν

µ

ν

ν

ν

µµµ

Λ=Λ=

Λ==

∑

∑ −−

),(),( jj mppmpP ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ µµ

=

We now introduce a label mj to denote all other degrees of freedom (i.e., all the other

total angular momentum orientations), and thus consider state-vectors |ΨΨΨΨ(p,mj)〉 with:

),(e),(),( j

ap

i

j mpmpaU ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ

∑−

= µ µ

µ

h1

∑′

′

′ΛΛ=

j

j

j

m

j

m

mj mppCmpU ),()],([),()( ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΛ

59](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-59-320.jpg)

![In other words, if a system is confronted with a homogeneous Lorentz transformation

ΛΛΛΛ, the momentum p is changed to Λp. According to Pµ |ΨΨΨΨ(p,mj)〉=pµ |ΨΨΨΨ(p,mj)〉, the one-

particle state must possess an eigenvalue of Λp as well:

in which U(ΛΛΛΛ,a)Pµ U−1(ΛΛΛΛ,a)=Σν [Λ−1]ν

µ Pν has been used for the Lorentz transformed

momentum generator. It can be seen then that U(ΛΛΛΛ)|ΨΨΨΨ(p,mj)〉 is a linear combination of

the states |ΨΨΨΨ(Λp,m′j)〉, where:

and this, believe it or not, does leave the momenta of all the particle states invariant.

∑∑ ′

′

+

−=′

′

′ΛΛ≡′ΛΛ=

j

jj

j

j

j

m

j

j

mm

j

jm

j

m

m

j

j mppmppmpU ),(),(),()],([),()( )()(

ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ DDΛ

),()(),(),( 2

o jjj mpcmmpppmpPP ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ == ∑∑ µ

µ

µ

µ

µ

µ

),()()(

),(])[(),()]()()[(),()0,( 1

j

jjj

mpUp

mpPUmpUPUUmpUP

ΨΨΨΨ

ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ

Λ

ΛΛΛΛΛ

µ

ν

ν

ν

µµµ

Λ=

Λ== ∑−

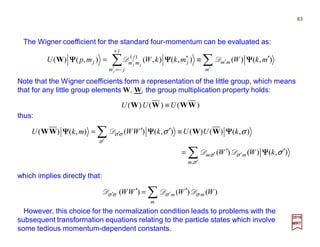

in which Dm′jmj

( j) (Λ,p) is termed the Wigner coefficient and, as said previously, they

depend on the irreducible representations of the Poincaré group.

As a special example, the Casimir operator Σµ Pµ Pµ cannot change the value of the

momentum (i.e., its an invariant – as also stated previously):

2017

MRT

60](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-60-320.jpg)

![Hence, to distinguish each state, the standard four-momentum given by kµ =[moc,0,0,0] is

chosen, from which all momenta can be achieved by means of a pure Lorentz boost:

which implies that there exists a subgroup of elements consisting of some arbitrary

Wigner rotations, W, and this subgroup is called the little group.

µ

ν

ν

ν

µ

kkW =∑

Notice that a simple three-dimensional rotation, W (which is an element of the

Poincaré group), will render the standard four-momentum invariant:

It is important to distinguish that this little group is not unique in the Lorentz group but it

is actually isomorphic to other subgroups under a similarity transformation. This is

because there is no well-defined frame for the standard momentum kµ due to the

equivalence principle in special relativity.Thedefinitionofthelittle group is dependent

on the choice of the standard momentum as well as the Lorentz transformation Λ.

Wigner’s Little Group

(N.B., the standard four-momentum is non-unique and it also depends on the charac-

teristics of the particle, e.g., whether it is a massive or a massless particle).

kpLp )(=

2017

MRT

),(),(),(),(),( 2

o jjjjjj mkmmkmkmkcmmkH ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ h=== J0p and&

In this momentum rest frame, the state |ΨΨΨΨ(k,mj)〉 is specified in terms of the eigen-

values of the Hamiltonian H=p0, the momentum p, and the z-component of the total

angular momentum operator J as:

61](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-61-320.jpg)

![When L(p) is

applied to k we

get the momentum

p. When ΛΛΛΛ is applied

next to p it becomes

Λp. When L−1(Λp) is

applied to Λp we

recover k!

So, the only functions of pµ that are left invariant by all proper orthochronous Lorentz

transformations Λµ

ν are the invariant square p2 =Σµν ηµν pµ pν, and p2 ≤ 0, also the sign of

p0. Hence, for each value of p2, and (e.g., for p2 ≤0) each sign of p0, we can choose a

‘standard’ four-momentum, kµ, and express any pµ of this class as:

where Lµ

ν is some standard Lorentz transformation that dependsonpµ,andalso implicitly

on our choice of the standard kµ. We can define the states |ΨΨΨΨ(p,mj)〉 of momentum p by:

∑=

ν

ν

ν

µµ

kpLp )(

Wigner’s little group is the Lorentz transformation

L−1(Λp) ΛΛΛΛL(p) that takes k to L(p)k =p, and then to

Λp, and then back to k, so it belongs to the

subgroup of the homogeneous Lorentz group.

Operating on this equation with an arbitrary homogeneous

Lorentz transformation U(ΛΛΛΛ), we find:

k µ =[moc,0,0,0]

pµ =Σν Lµ

ν ( p)kνΛ p=Σν Λ0

ν pν

L−1(Λ p) L(p)

ΛΛΛΛ

),()]([)(),( jj mkpUpNmp ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ L=

N(p) is a numerical normalization factor to be chosen on the next slideandwhere U[L(p)]

is a unitary operator associated with the pure Lorentz ‘boost’ thattakes[moc,0] into[p0,p].

The transformation Wµ

ν (i.e., L−1(Λp) ΛΛΛΛL(p) = W(Λ, p)) thus

leaves k µ invariant: Σν Wµ

ν kν =kµ. For any Wµ

ν satisfying this

relationship, we have:

),()]()([)]([)(

),()]([)(),()(

1

1

j

jj

mkppUpUpN

mkpUpNmpU

ΨΨΨΨ

ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ

LΛLL

LΛΛ

4444 34444 21

=

−

ΛΛ=

=

∑

+

−=′

′

′Λ=Λ

j

jm

j

j

mmj

j

jj

mkpmkpU ),()],([),()],([ )(

ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ WW D

where the coefficients Dm′j mj

( j ) [W(Λ, p )] furnish the

representation of the little group.

2017

MRT

62](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-62-320.jpg)

![Normalization Factor

Using W=L−1 ΛΛΛΛL and inserting into U(ΛΛΛΛ)|ΨΨΨΨ(p,m)〉=NU[L(Λp)]U[L−1(Λp)ΛΛΛΛL(p)]|ΨΨΨΨ(p,m)〉

and using U(W)|ΨΨΨΨ(k,m)〉=Σm′ Dm′ m(W )|ΨΨΨΨ(k,m′)〉 we get:

or, recalling the definition |ΨΨΨΨ〉=NU[L(p)]|ΨΨΨΨ〉, we finally get:

2017

MRT

for which

The normalization factor N(p) is sometimes chosen to be N(p)=1 but then we would

need to keep track of the p0/k0 factor in scalar products. Instead, the convention is that:

The normalization condition is achieved using the scalar product:

∑′

′ ′ΛΛ

Λ

=

m

mm mppW

pN

pN

mpU ),()],([

)(

)(

),()( ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ DΛ

∑′

′ ′ΛΛ=

m

mm mkpUpWpNmpU ),()]([)],([)(),()( ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ LΛ D

0

0

)(

p

k

pN =

mmmpmp ′−′=′′ δδ )(),(),( ppΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ

)()(),(),(

2

kk −′=′′ ′ δδ mmpNmpmp ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ

)(

)()(

)(

)(

)(

)( 0

0

0

0

pE

pE

p

p

pN

pN

p

k

pN

Λ

=

Λ

=

Λ

⇒

Λ

=Λ

and

64](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-64-320.jpg)

![The explicit form for W(Λ,p) is:

where the angle θ is defined by tanhθ =√[(p0)2 −mo

2c4]/p0 and the components of the

particle momentum are given by pi (i=1,2,3). The Lorentz boost L(p) transforms the

standard momentum kµ to momentum pµ. In addition, the general Lorentz transformation

ΛL for ‘pure boost’ only is written as:

( )ppkpLpLpW pL

Λ→ →ΛΛ=Λ Λ− )(1

)(),(),(

−+

= ji

ji

i

j

ppp

p

pL

ˆˆ)1(coshsinhˆ

sinhˆcosh

)(

θδθ

θθ

−+

=Λ ji

ji

i

j

L

nnn

n

ˆˆ)1(coshsinhˆ

sinhˆcosh

ξδξ

ξξ

and it can be shown that this is an element of the little group associated with the

standard vector kµ. (N.B., L(Λp) is the Lorentz boost of the momentum (Λp)µ from

standard momentum vector kµ ). Then the Wigner transformation corresponding to the

present choice of kµ is a SO(3) rotation. Furthermore, the Lorentz boost L(p) can be

computed from the boost generator Ki =Mi0=ih(xi ∂0 −x0∂i) where L(p)=exp(−icθ p•K/h).

The explicit form of L(p) is given by:

ˆ

where n is a unit vector along the direction of the boost. This transforms the

momentum pµ to a Lorentz-transformed momentum (Λp)µ.

ˆ 2017

MRT

66

One-Particle States – con’d](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-66-320.jpg)

![Considering now a Taylor expansion of the Wigner transformationW(Λ,p)=

L−1(Λp)ΛL(p) as well as the explicit form of the matrix for L(p) just obtained for an

arbitrary Lorentz transformation Λ:

in which the Lorentz boosts, L(p) and L(Λ,p) and the arbitrary Lorentz transformation, Λ,

are parametrized in terms of its generators. In addition, the spatial component of the

Lorentz-transformed momentum is given by pΛ=Λp (N.B., The corresponding Lorentz

boost for the Lorentz transformed momentum starting from the standard vector, kµ, is

given by tanhθ′=|pΛ|/(Λp)0, in which L(Λp)k=Λp).

K+−=Λ µν

µν

Mω

2

1

)ω( 1

thus:

KpKp •−−•′

−

≡

ΛΛ=Λ

ˆω

2

1

ˆ

1

eee

)()(),(

Λ θθ µν

µν

hh

ci

M

ci

pLpLpW

βα

β

αβα

βµν

µναα

pppM

i

pp ]ω[]ω[

2

)( +≡−≅Λ

Consider the inifinitesimal Lorentz transformation being parametrized by the anti-

symmetric tensor ωµν (expressed to first order terms of ω):

2017

MRT

Note that in the above and from now on, we restored the summation convention

where we sum over any space-time index which appears twice in the same term.

67](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-67-320.jpg)

![A Taylor series expansion of the Wigner transformation is considered as fallows:

thus:

In the ‘second term’ of this last equation the expression can be re-written as:

K

K

+

∂

ΛΛ∂

+=

+

∂

Λ∂

+Λ=Λ

=

−

=

=

0ω

1

0ω

0ω

ω

)]()([

ω

ω

),(

ω),(),(

µν

µν

µν

µν

pLpL

pW

pWpW

1

K

K

+

−Λ+

∂

Λ∂

+=

+

∂

Λ∂

Λ+

Λ

∂

Λ∂

+≅Λ

=

−

=

−

=

−

=

−

)(

2

)(ω)(

ω

)(

ω

)(

ω

)ω(

)(ω)()ω(

ω

)(

ω),(

0ω

1

0ω

1

0ω

1

0ω

1

pLM

i

pLpL

pL

pLpLpL

pL

pW

µν

µν

µν

µν

µν

µν

µν

µν

1

1

in which the substitution Λp=p′ has been made and, in general, L−1(p′)=ηηηηLT(p′)ηηηη.

2017

MRT

68

−+

′

′′

−

′

+

′

−

′

−

′

∂

∂

+=

∂

Λ∂

=

=

−

22

o

0

o

o

2

o

0

0ω

22

o

0

o

o

2

o

0

0ω

1

11

ω

ω)(

ω

)(

ω

p

pp

cm

p

cm

p

cm

p

cm

p

p

pp

cm

p

cm

p

cm

p

cm

p

pL

pL

kj

kj

j

k

ji

ji

j

i

δδ

µν

µν

µν

µν

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-68-320.jpg)

![Now, since (Λp)α≅pα−(i/2)[ωµν Mµν]α

β pβ≡pα+[ω]α

β pβ, we get (h=c=1):

and since ξ i =ω0i =−ωi0 and θ k =εijk ωij as well as Ji =εijk Mjk and Ki =Mi0:

βα

β

βα

βµν

µν

µν

α

µν

ppM

ip

]ω[][ω

2ω

)(

ω

0ω

≡−≅

∂

Λ∂

=

in which the axial vector is given by θθθθ=[θ 1,θ 2,θ 3]† and mi =(p××××θθθθ)i as well as:

−

•

≡

−

•

=

−

=

−

=

+−=++−=

ii

ii

k

jkjii

jj

j

k

kjii

j

k

ki

i

ji

ji

i

i

i

i

p

ppp

p

p

p

pJK

i

pMMM

i

p

mp

ξpp

θpp

ξpp

ξ

ξθεξ

ξ

θεξ

ξ

θξ βββ

β

α

0

00

0

0

0

0

0

)ˆ(

)ˆ(

)ˆ(0

]22[

2

]ωωω[

2

]ω[

××××

−−−=

∂

′∂

∑

= nm

nnmiii

i

pppp

p

][ˆˆ][

1

ω

)ˆ(

ω 00

0ω

mpmp

p

ξξµν

µν

At this junction, the sum Σmn pm[p0ξn −|p|mn] describes the relation between the

components of the momentum and its Lorentz boost.

ˆ

2017

MRT

ˆ

69](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-69-320.jpg)

![Assuming that any sum over the cross-terms is zero for m≠n, that is:

)ˆ(][ˆ 00

ξpmp •=−∑ ppp

nm

nnm

ξ

in which the boost vector is given by ξξξξ=[ξ 1,ξ 2,ξ 3]†. With the axial vector, θθθθ=[θ 1,θ 2,θ 3]†,

θθθθ and ξξξξ become the parameter vectors associated with the infinitesimal Lorentz

transformation Λ. In addition, the vector normal to both the axial and momentum vectors

is given by m=p××××θθθθ.

Jmpξp

p

Km

p

pξpξ

pmξp

p

m

p

ξp

m

p

ξp

ξp

p

m

p

m

p

ξp

p

•

−

−+•

−•

−−≡

−

−−+•

−

−+•

−

=

−+

•

−

−−

−+−

+−•

=

∂

Λ∂

=

−

))))××××××××

××××××××

ˆ(2)ˆ(1ˆ)ˆ(1

)ˆ(2)ˆ(1ˆ)ˆ(1

ˆ)ˆ(10

ˆˆ1ˆˆ)ˆ(]ω[ˆ]ω[ˆ1

)ˆ(

)(

ω

)(

ω

0

o

0

oo

0

o

0

0

o

0

o

0

oo

0

o

0

oo

0

o

0

o

oo

0

o

0

o

0

oo

0

oo

0

o

0ω

1

p

m

p

i

mm

p

m

p

i

p

m

p

m

p

m

p

m

p

m

p

m

p

m

p

pp

m

p

m

p

m

p

m

p

pp

mp

pppp

m

p

mm

p

mm

p

m

pL

pL

nkinniii

kkk

kj

kj

j

k

jiijjiii

jj

εξ

ξ

δξ

ξ

β

β

β

β

µν

µν

ˆ

Our equation for ωµν [∂L−1(Λp)/∂ωµν ]|ω=0L(p) above (i.e. the ‘second term’) can be

simplified by using the Lorentz boosts from the matrices for L(p) and ΛL further up, and

this can be worked out as:

2017

MRT

70](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-70-320.jpg)

![The third term in our Taylor expansion for W(Λ,p) above (i.e., the term obtained above

ωµν [L−1(Λp)(−½i Mµν )]|ω=0L(p)) can also be simplified in terms of its matrix elements

(Note that the expression (−½i ωµν Mµν ) can be re-written as the matrix [ω]):

Jmpθξp

p

Km

p

pξpξ

mp

p

ξm

p

ξp

m

p

ξp

m

p

ξp

m

p

ξp

•

−+−−+•

−•

−−−≡

−+−

−•

−

−

−+•

−

=

−

−

+−

−−•

−

−

−•

−

−

=

−+

−

′′

−+

′

−

′

−

′

=′−

))))××××××××

))))××××××××

ˆ(1)ˆ(

2

ˆ)ˆ(1

ˆ(1ˆ)ˆ(

ˆ)ˆ(10

)ˆˆˆˆ(ˆ)ˆ(

)(ˆ)ˆ(0

ˆˆ1

0

ˆˆ1

)](][ω)][([

o

00

oo

0

o

0

o

0

ooo

o

0

o

0

o

0

oo

0

o

o

0

oooo

o

0

o

0

oo

o

0

o

0

o

0

o

oo

0

o

0

o

oo

0

1

m

pp

i

mm

p

m

p

i

m

p

mm

p

m

mp

m

p

m

p

m

p

m

p

pmmp

m

mp

m

p

m

p

m

p

m

mp

m

p

m

p

m

mp

m

p

pp

m

p

m

p

m

p

m

p

pp

m

p

m

p

m

p

m

p

pLpL

mlimm

m

iii

kkk

lilimmlil

il

iiii

lll

lk

lk

k

l

mmkjj

k

ji

ji

i

j

εθξ

ξ

θεξξξ

ξ

δ

θεξ

ξ

δ

in which ωµν [∂( p′)α/∂ωµν]|ω=0 above has been used for the matrix reprentation of the

arbitrary infinitesimal Lorentz transformation Λ(ω).

2017

MRT

71](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-71-320.jpg)

![After some careful re-grouping of the terms from all the matrix elements given in ωµν

[∂L−1(Λp)/∂ωµν]|ω=0L(p) and [L−1(p′)][ω][L(p)] just obtained, the boost terms in our

expansion for W(Λ,p) has cancelled out completely and leaving behind the rotation

terms:

where Ω( p) k =−ε ijk [ωij −(piω0j −pj ω0i)/( p0 +mo)] is the Wigner angle and Jk =½ε ijk Mij

is the rotation generator for the Poincaré group.

Thus, we obtain:

J1

1

1

Jθξp

p

1

•+=

−

−

−+=

−−

−

−=

•

+

−

−≡Λ

)(

)ωω(

)(

1

ω

)(

)(

1

)(

)(

),(

00

o

0

o

0

o

0

pi

Mpp

mp

i

Mpp

mp

i

mp

ipW

ji

ijjiji

jin

njiijji

n

θεξξ

××××

−

−

−+=Λ njinnmppW εθ)ˆ(

)(

0

00

)],([ o

0

ξp

p

1 ××××

2017

MRT

72](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-72-320.jpg)

![The Wigner angle can be re-written as a sum of the contributions from the rotation and

the boost:

Here the angle of rotation are represented by the Euler angles θk =ε ijk ωij and the boost

parameter ξi =ξ ni =ω0i. The finite Wigner transformation is given by:

)ˆˆ(

)(

o

0

o

0

pn

p

θ

ξp

θ

××××

××××

mp

mp

p

+

−≡

+

−≡

ξ

J•

∞→

=

Λ=Λ

i

N

N

p

N

WpW

e

,

ω

lim]),ω([

ˆ

2017

MRT

73](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-73-320.jpg)

![The representation matrix Dmjσ

( j) [W(Λ,p)] can be constructed from the angular

momentum generators Ji explicitly, depending on the angular momentum of the particle.

For example, spin-1/2 particles will be considered to have appropriate generators as

given by J=½σσσσ according to the isomorphism between the proper Lorentz group and the

SU(2)⊗SU(2) algebra.

J•

=Λ i

pW e),(

The Wigner transformation corresponding to an arbitrary Lorentz transformation Λ is

given by:

where Ω( p)k =−½ε ijk [(piωj

0 −pj ωi

0)/(p0 +mo)] and Jk =½ε ijk Mjk in the absence of rotation.

This can also be written as:

o

0

o

0

ˆ

)(

mpmp

p

+

=

+

−≡

pnξp ××××××××

ξ

Here the boost parameters are represented by ξi =ξni =ωi

0. For an infinitesimal variation

ωµν, the transformation matrix is (e.g., spin-1/2 case described above):

ˆ

+

−

+

•+

+

−=

−

•+

−≅

•+

=Λ

×

××

3

o

0

o

0

2

o

022

32

2222

)2/1(

)(2

ˆ

!3

1

)(2

ˆ

)(2

ˆ

!2

1

1

2!3

1

22!2

1

1

2

sin

2

cos)],([

mpmp

i

mp

I

iIiIpW

p

pnpn

σ

pn

σσ

×××××××××××× ξξξ

D

2017

MRT

74](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-74-320.jpg)

![The representation matrix becomes (i.e., spin-1/2 case):

For the sake of convenience, I2×2 is assigned as the 2×2 identity matrix, and σσσσ as the

‘vector’ that is comprized of the Pauli 2×2 matrices [σ1,σ2,σ3]. (Note that the Wigner

angle |ΩΩΩΩ|=Ω is dependent on both the rotation and boost parameters for an arbitrary

Lorentz transformation Λ. In addition, notice that an additional normalization factor of

√[p0/(Λp)0] has been appended to the matrix so as to maintain the condition given

D†(Λ,p) D(Λ,p)=p0/(Λp)0 I2×2).

by using the well known Pauli spin vector σσσσ relation (σσσσ•a)(σσσσ•b)=(a•b)+iσσσσ•(a××××b) and

remembering that ΩΩΩΩ=ΩΩΩΩ /|ΩΩΩΩ|. Thus, with the well known sinξ=ξ−ξ 3/3!+ξ 5/5!−… and cosξ

=1−ξ 2/2!+ξ 4/4!−… identities:

•+

Λ

=Λ

2

sin)ˆ(

2

cos

)(

)],([ 0

0

)2/1(

σ1 i

p

p

pWD

+

−•+

+

−

Λ

=

+

•+

•+

Λ

=

Λ

=Λ

×

×

•

KK

K

32

220

0

2

220

0

2

0

0

)2/1(

2!3

1

2

)ˆ(

2!2

1

1

)(

2!2

1

2!1

1

)(

e

)(

)],([

σ

σσ

σ

iI

p

p

iiI

p

p

p

p

pW

i

D

2017

MRT

ˆ

75](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-75-320.jpg)

]([

)]()([)],([

)2/1()2/1(1)2/1(

1)2/1()2/1(

pLpL

pLpLpW

DDD

DD

ΛΛ≡

ΛΛ=Λ

−

−

The representation matrix D(1/2)[W(Λ,p)], in the absence of rotation, is this given by:

Ω

•+

Ω

Λ

=

•−

•+

+

+Λ+

Λ

=Λ

×

××

2

sin)ˆ(

2

cos

)(

2

sinh)]ˆ([

2

sinh)ˆ(

2

cosh)(

]))[((

)/(

)],([

220

0

22o

0

22

o

0

o

0

00

)2/1(

mσ

npσnp

iI

p

p

iImpI

mpmp

pp

pW

ξξξ

××××D

)ˆˆ(sinhsinh

2

1

coshcosh

2

1

2

1

)ˆˆ(

2

sinh

2

sinh

ˆ

2

sin

)ˆˆ(sinhsinh

2

1

coshcosh

2

1

2

1

)ˆˆ(

2

sinh

2

sinh

2

cosh

2

cosh

2

cos

pn

pn

m

pn

pn

•++

=

•++

•

+

=

θξθξ

θξ

θξθξ

θξθξ

××××

&

where coshθ =p0/mo and m=n××××p represents the axis of rotation of the equivalent Wigner

transformation (e.g., of the Dirac spinors in the spin-½ case). Here the parameters ξ and

n are defined in the same manner as the general Lorentz boost as given by the ΛL

matrix.

ˆ

ˆˆ

2017

MRT

ˆ

76](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-76-320.jpg)

![∑−=′

′

′ΛΛ

Λ

=Λ

j

jm

j

j

mmj

j

jj

mppW

p

p

mpU ),()],([

)(

),()( )(

0

0

ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ D

With the normalization and the understanding of D, our transformation thus becomes:

where Wα

µ (Λ,p)=(L−1)α

σ (Λp)⊗ Λρ

ν Lν

µ (p) is theWigner Rotation,k≡kµ =[k0 =moc,ki =0],

p≡pν =[p0 =E/c,pi ], and since U(W)|ΨΨΨΨ(k,mj)〉=Σm′j

Dm′jmj

( j) [W(Λ,p)]|ΨΨΨΨ(k,m′j)〉:

2017

MRT

since N(Λp)U[L(Λp)]|ΨΨΨΨ(k,m′j)〉=|ΨΨΨΨ(Λp,m′j)〉⇒U[L(Λp)]|ΨΨΨΨ(k,m′j)〉=N−1(Λp)|ΨΨΨΨ(Λp,m′j)〉

where the normalization constant is N(Λp)=√[k0/(Λp)0]. Finally we have:

),()],([)]([),(])()([)]([),()( 0

0

),(

1

0

0

jj

p

j mkpUpLU

p

k

mkpLpLUpLU

p

k

mpU ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ ΛΛ=ΛΛ=

Λ

−

WΛΛ

W

44 344 21

444 3444 21

),(

)(

0

0

)(

0

0

),()()],([

),()],([)(),()(

j

j

jj

j

jj

mp

j

m

j

mm

j

m

j

mmj

mkpLpW

p

k

mkpWpL

p

k

mpU

′Λ

′

′

′

′

′ΛΛ=

′ΛΛ=Λ

∑

∑

ΨΨΨΨ

ΨΨΨΨ

ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ

D

D

77

Isn’t this the most beautiful equation you’ve ever seen? So, this is how particle states

|ΨΨΨΨ( p,mj)〉 transform into when a Lorentz transformation Λ acts on it! That is, using a

quantum mechanical unitary operator U(Λ) that changes momentum p and spin mj!

6447481

64748p = L(p)k](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-77-320.jpg)

![Mass Positive-Definite

To define the mass positive-definite, we must recall a few definitions such as the unitary

quantum transformation for coordinate and angular momenta:

where P={P1,P2,P3}, J={M23,M31,M12} and K={M10,M20,M30} and their properties are

P

ρ†

=P

ρ

, M

ρσ †

=M

ρσ

and M

ρσ

=−M

σρ

. Now for the definition of invariance under a unitary

transformation of a homogeneous Lorentz Transformation Λ and a uniform translation a:

...ω

2

1

),ω( ++−=+ ρσ

ρσ

ρ

ρεε M

i

PU

h

11

),(),(),(),ω1(),( 1

jj mpmpaUUaU ΨΨΨΨΨΨΨΨ =Λ+Λ −

ε

which also applies to both momenta:

)(),(),(),(),( 11 µννµµνσ

ν

ρ

µ

µνµρ

µ

µ

PaPaMaUMaUPaUPaU +−ΛΛ=ΛΛΛ=ΛΛ −−

&

For the momentum, they commute with each other:

0],[ =νµ

PP

but for the angular momentum they do not:

ρµσσµρρσµ

ηη PPMPi −=],[

nor do the angular momenta together commute:

ρµσνρνσµνσµρµσνρρσµν

ηηηη MMMMMMi +−−=],[

As comparison, we show the case when Λ=1 then a= 0 and a rotation around the 3-axis:

θµ

µ

pJ ˆ

3 e)0,(e),1(

•−−

== hh

i

aP

i

RUaU and

( ))()0,( Λ=Λ UU

2017

MRT

78](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linked-inslides-qft-130507130813-phpapp02/85/Part-IV-Quantum-Fields-78-320.jpg)

(

Ω•−•−

′ ′=′=Ω

pJJ

hhD

∑∑ ′

′

′

′Ω=′Ω′=Ω

j

jj

j m

j

j

mm

m

jjjj mRmmjRmjmjR )]([,)]([,,)]([ )(

DDD

θϕ

θϕ j

jjjj

j

jj

mi

kmmkmmj

mi

k jjjj

jjjjkj

mm

kmmkmjkmjk

mjmjmjmj

e

2

sin

2

cose

)!()!()!(!

)!()!()!()!(

)1(),,(

222

)(

+−′−′−+

′

Ω

Ω

+−′−′−−+

′−′+−+

−=Ω ∑D

∑∑∑ Ω=′⇒Ω= ′

l

ll

l

l

l

l

l

ll llll

m

mm