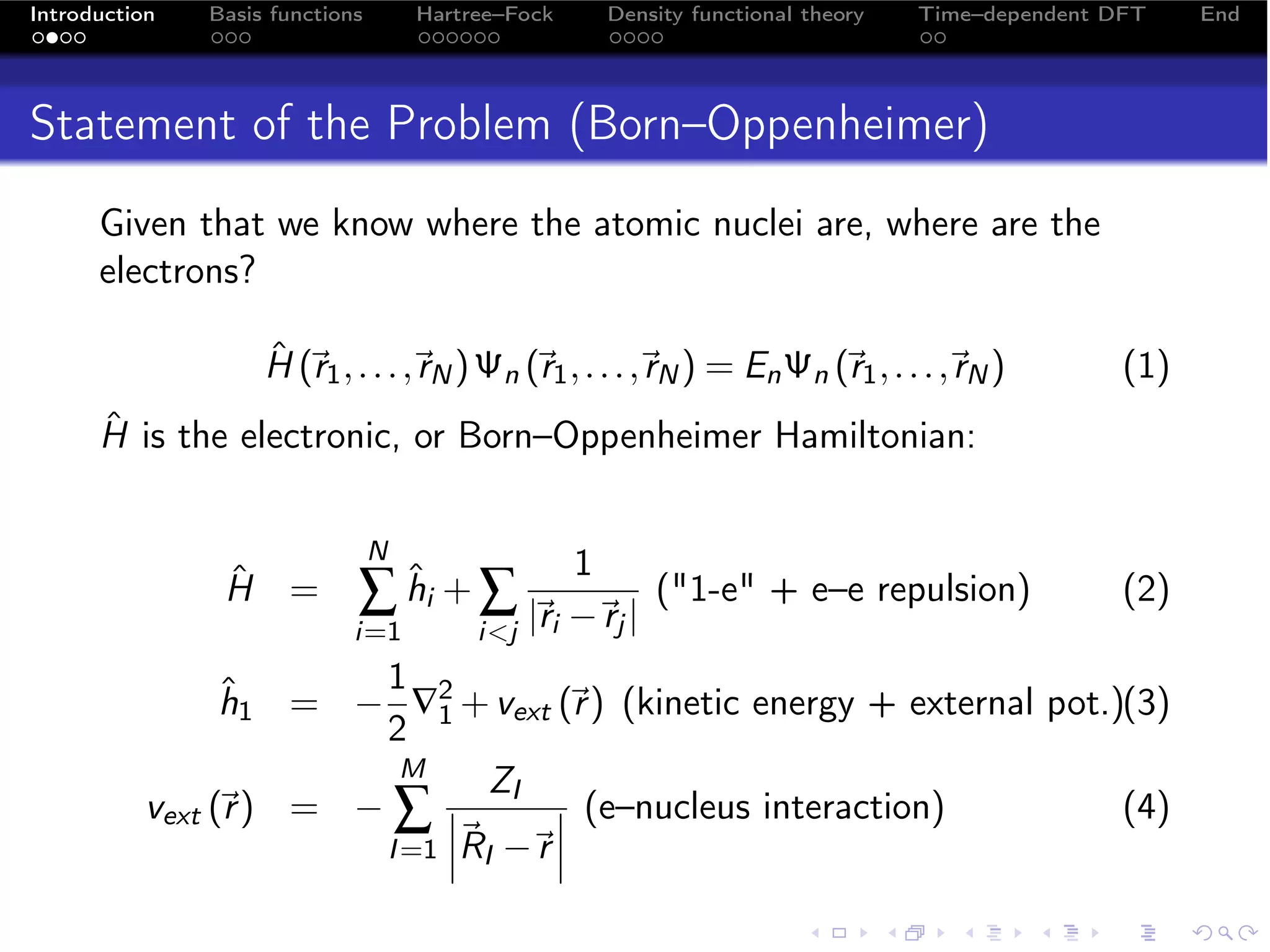

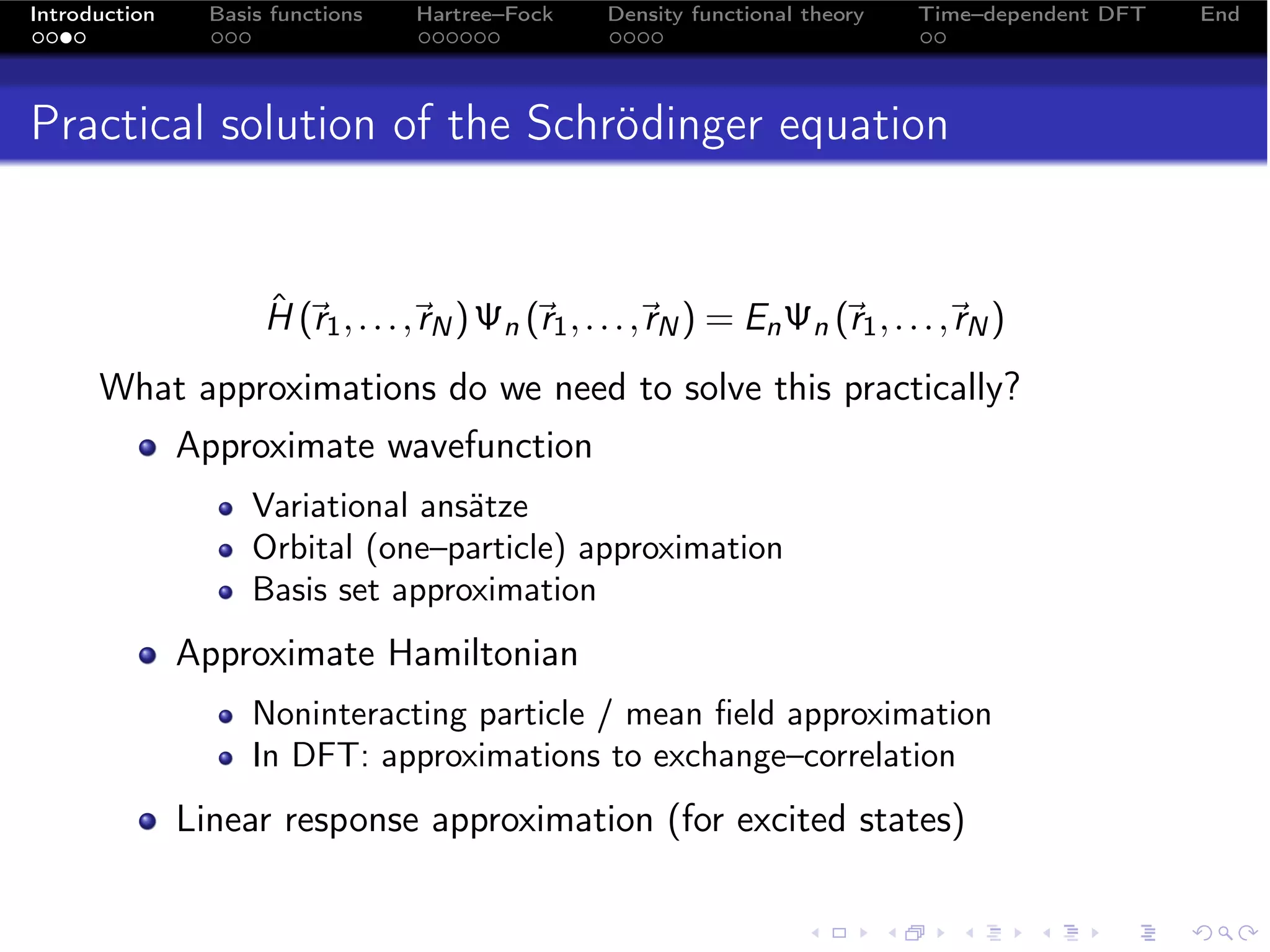

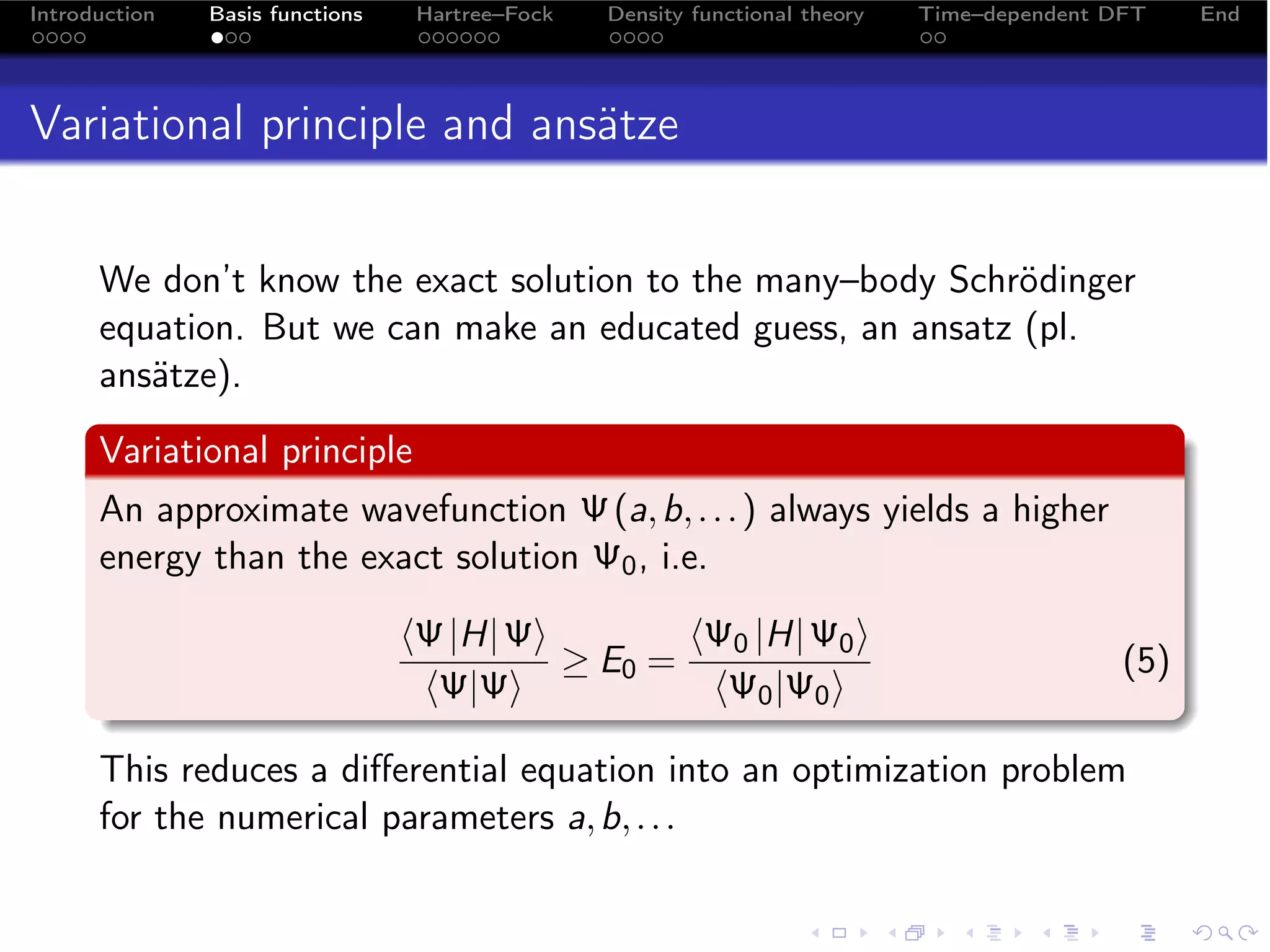

The document provides an overview of time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) for computing molecular excited states. It begins with an introduction to the Born-Oppenheimer approximation and variational principle. It then discusses the Hartree-Fock and Kohn-Sham equations as self-consistent field methods for calculating ground states, and linear response theory for calculating excited states within TDDFT. The contents section outlines the topics to be covered, including basis functions, Hartree-Fock theory, density functional theory, and time-dependent DFT.

![Introduction Basis functions Hartree–Fock Density functional theory Time–dependent DFT End

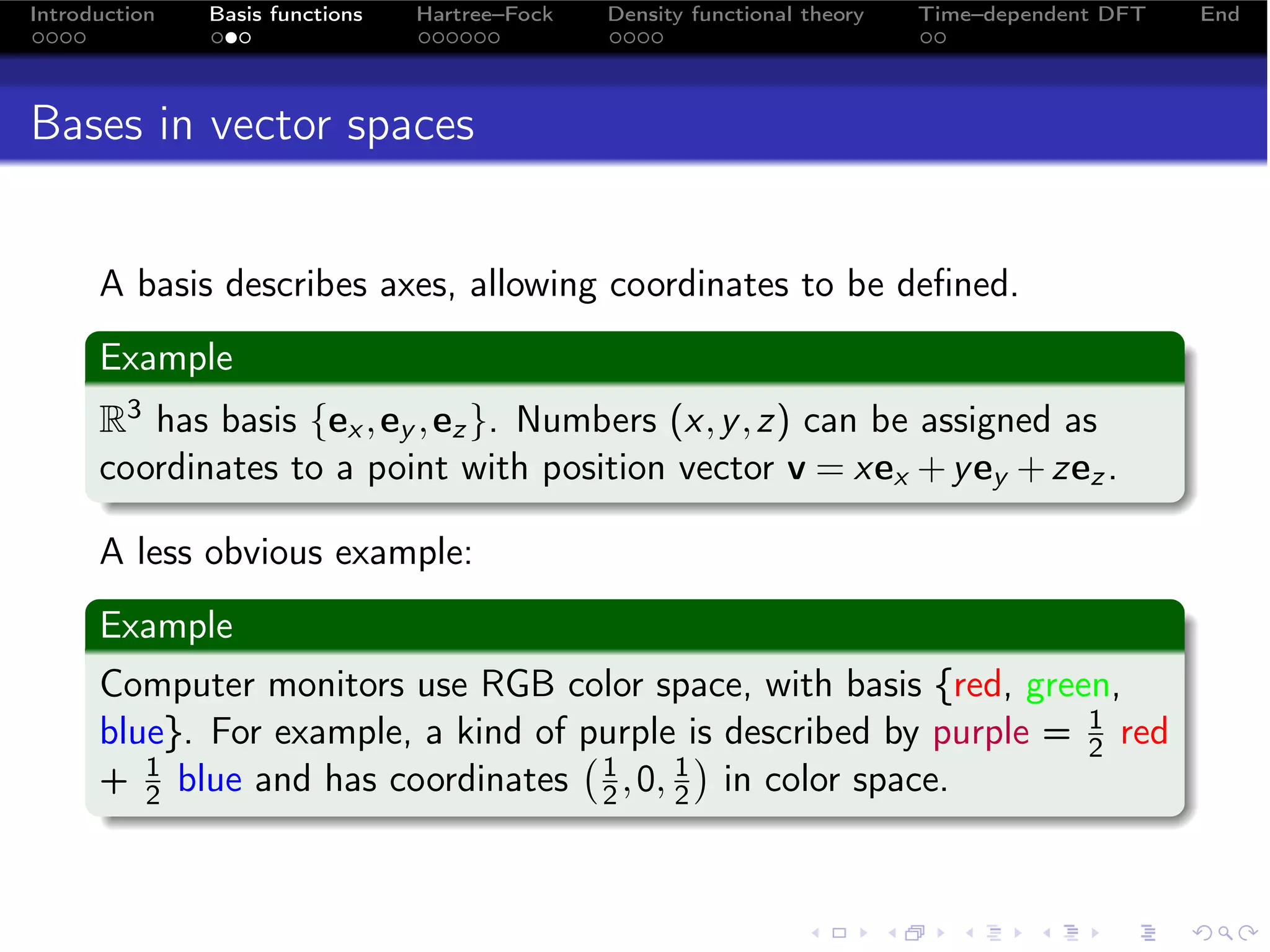

Bases in function spaces

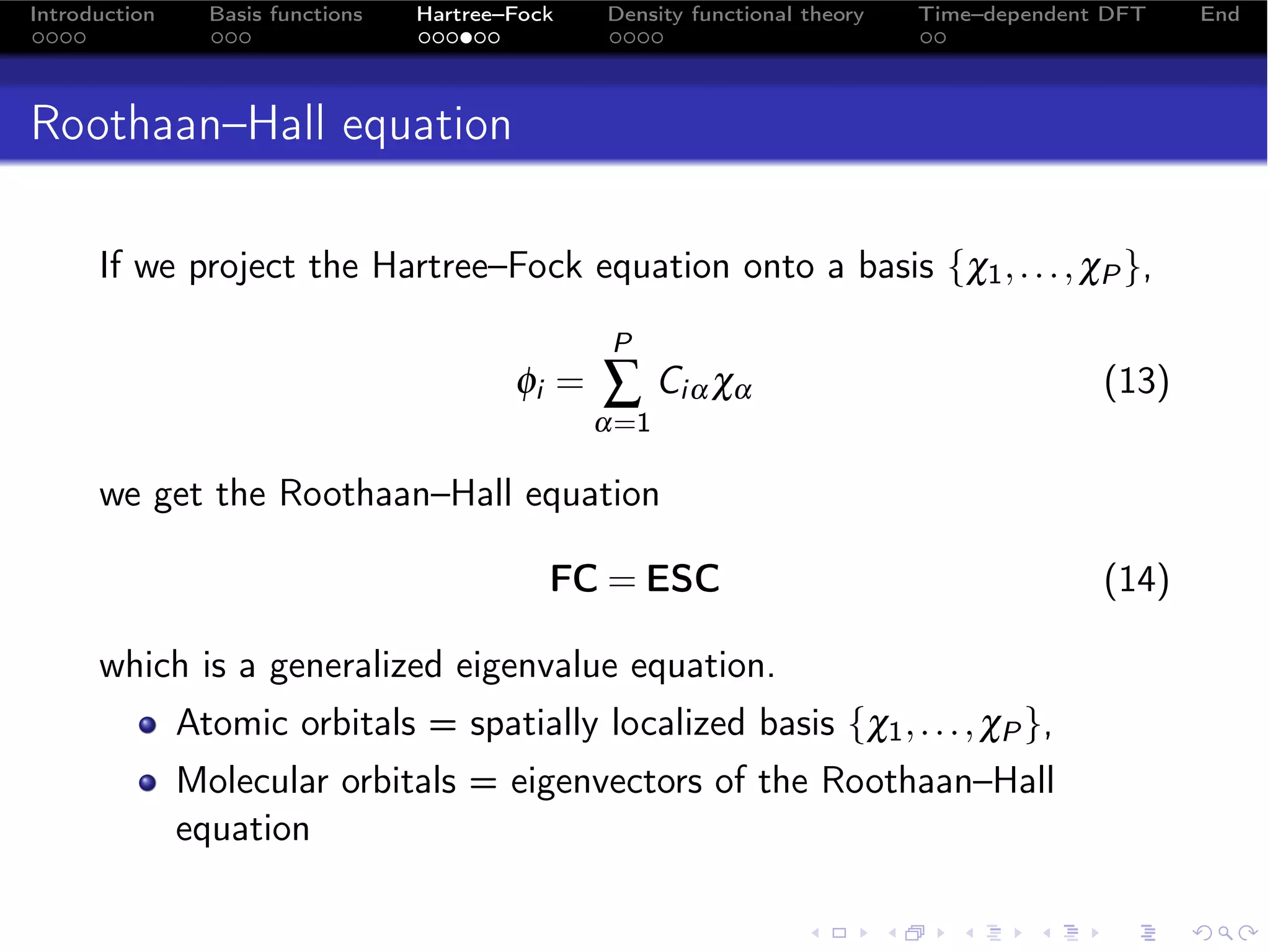

Basis functions describe “axes” in function space. If you have a

collection of mutually orthogonal, real functions φ1 (x) , . . . , φn (x)

that span the entire space of functions, then

f (x) = ∑ ci φi (x) (7)

i

whose coefficients are given by projections onto the basis

N f (x) φi (x) dx

´

ci = R´ 2

(8)

RN φi (x) dx

Then the function f has “coordinates” (c1 , c2 , . . . ) in the basis

spanning the function space.

Example

Functions over [−π, π] have Fourier series expansions, whose basis

functions are 1, sin x, cos 2x, sin 3x, cos 4x, . . .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/efrc-lunch-100311234948-phpapp01/75/A-brief-introduction-to-Hartree-Fock-and-TDDFT-11-2048.jpg)

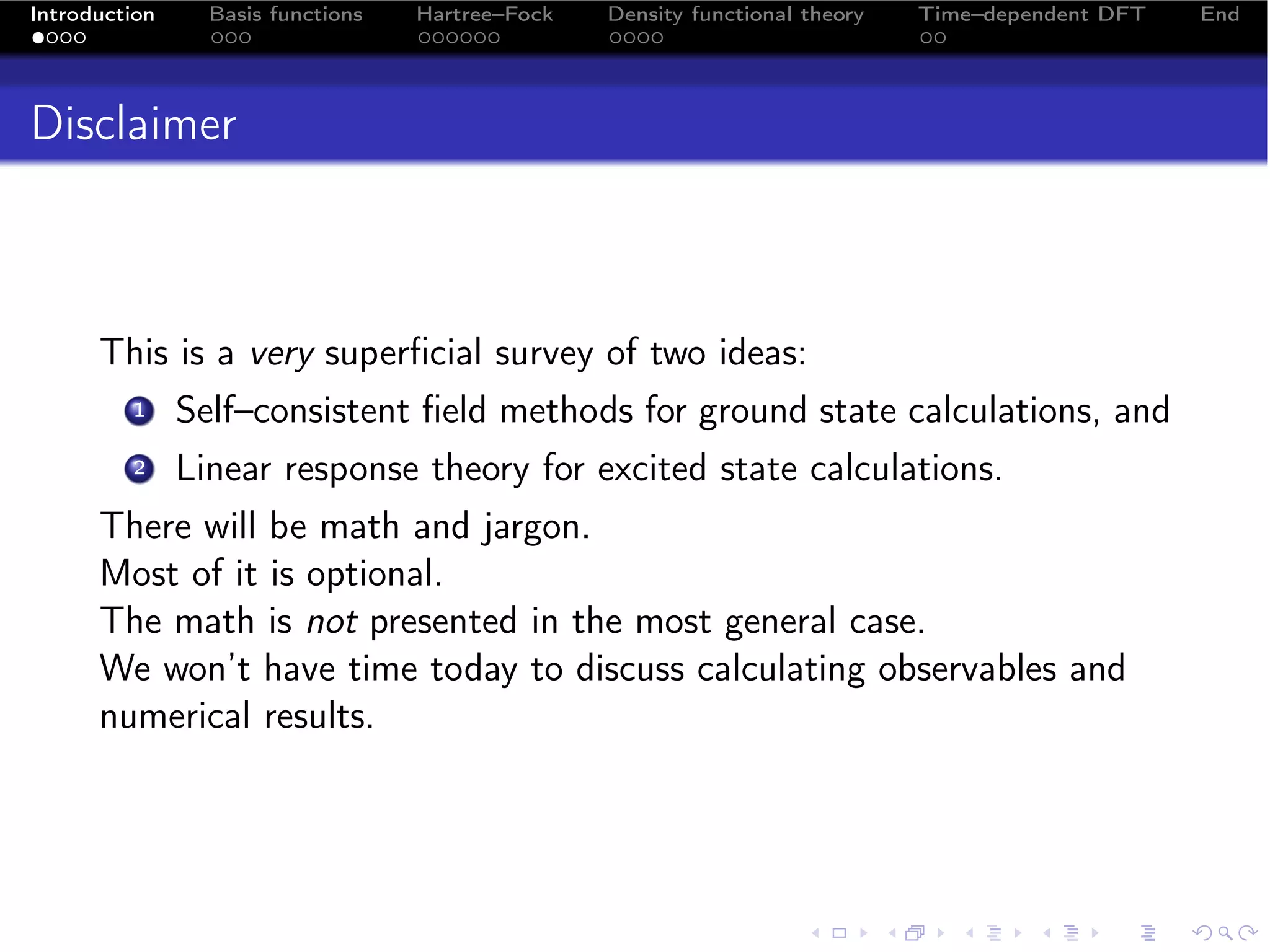

![Introduction Basis functions Hartree–Fock Density functional theory Time–dependent DFT End

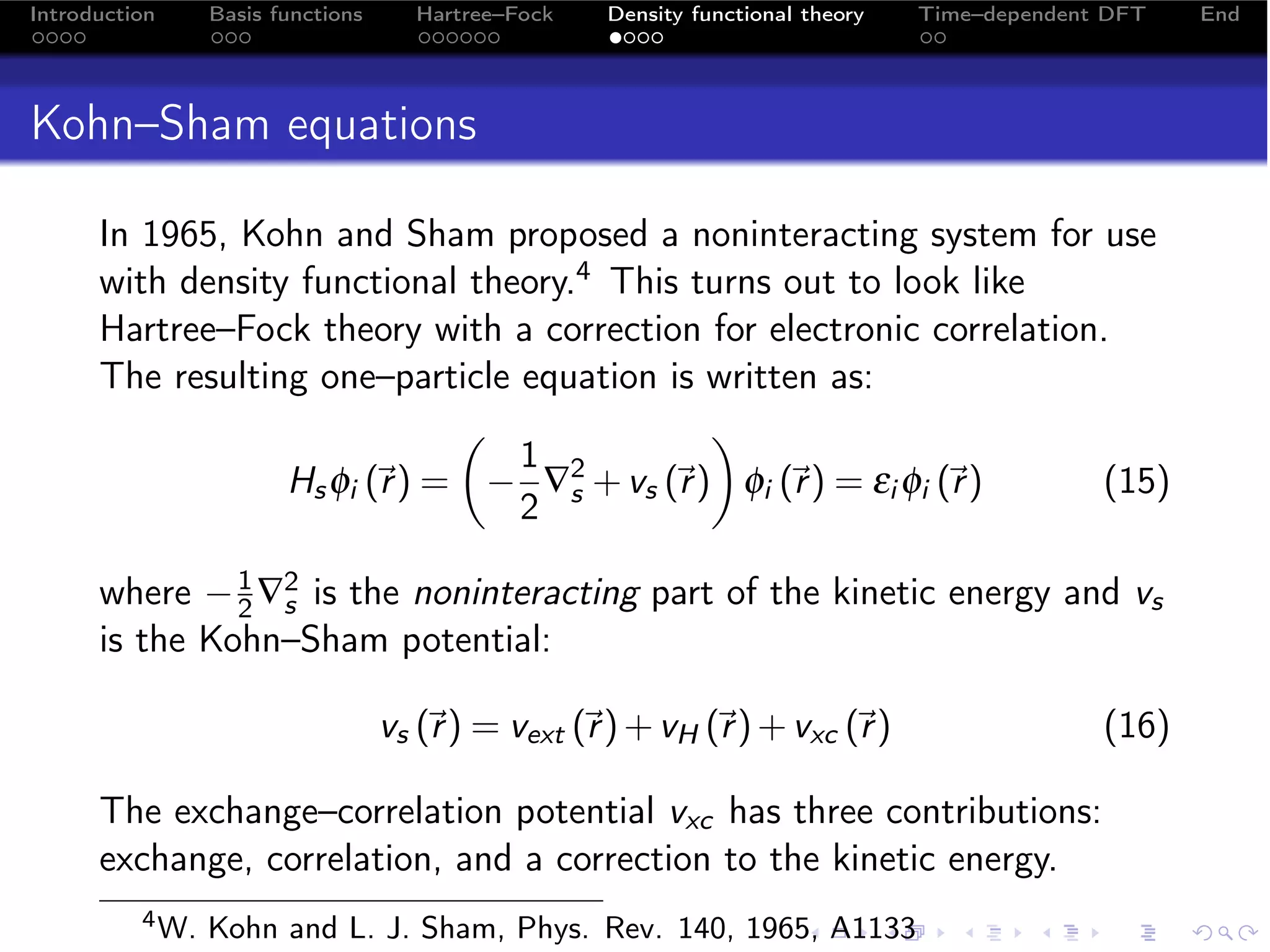

Kohn–Sham is a density functional theory

The Kohn–Sham equation is equivalent to finding the density ρ

that minimizes the energy functional

ˆ

E [ρ] = vext (r ) ρ (r ) d + Ts [ρ] + VH [ρ] + Exc [ρ]

r (17)

R3

1 N

ˆ

Ts [ρ] = − ∑ φi (r ) ∇2 φi (r ) d

r (18)

2 i=1 R3

1 ρ (r ) ρ (r )

ˆ

VH [ρ] = + d d

r r (19)

2 R6 |r −

r |

where the density is constructed from

N

ρ (r ) =

∑ |φi ( )|2 = ∑

r Ci µ Ciν χµ (r ) χν (r )

(20)

i=1 µνi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/efrc-lunch-100311234948-phpapp01/75/A-brief-introduction-to-Hartree-Fock-and-TDDFT-19-2048.jpg)

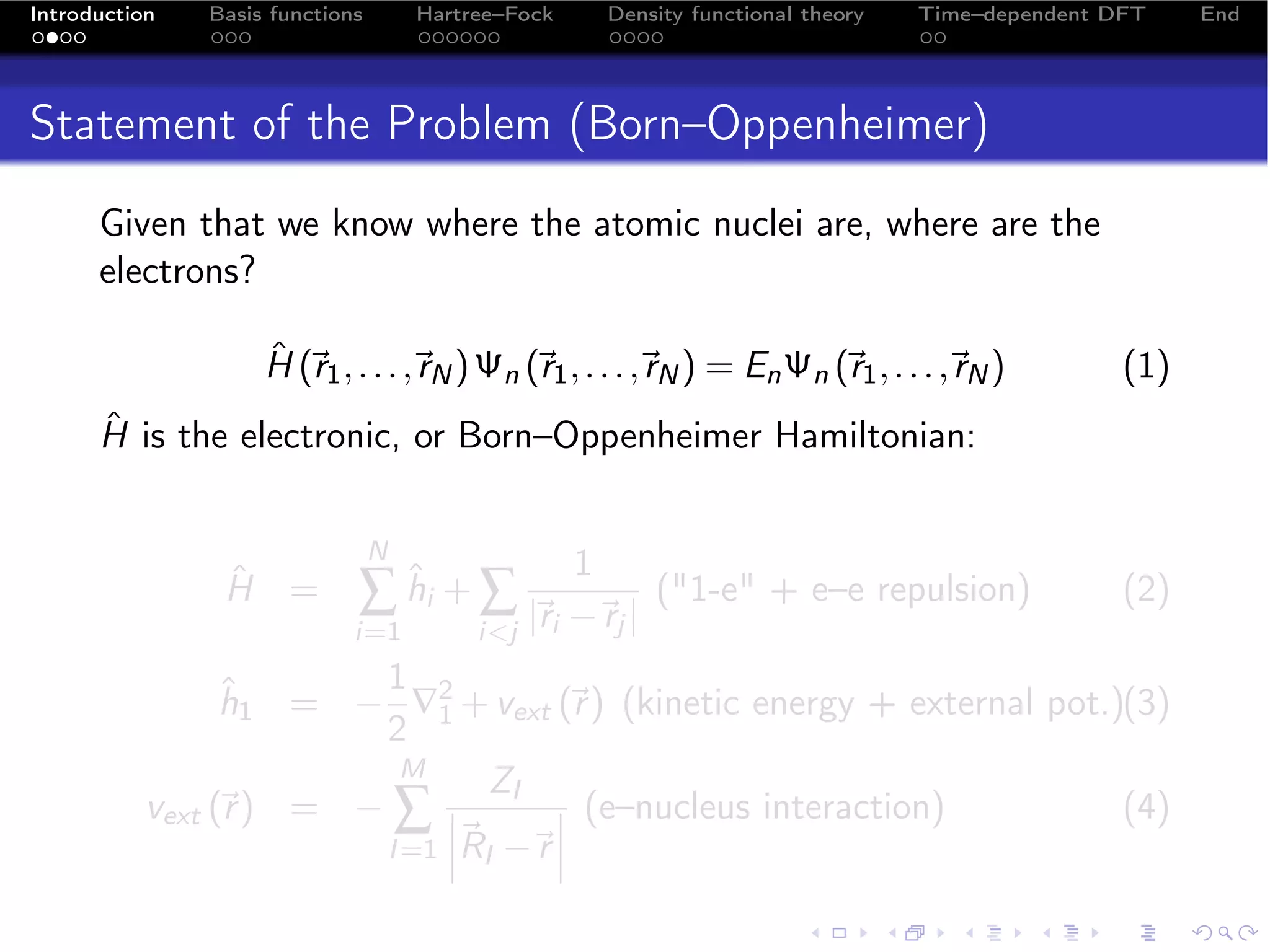

![Introduction Basis functions Hartree–Fock Density functional theory Time–dependent DFT End

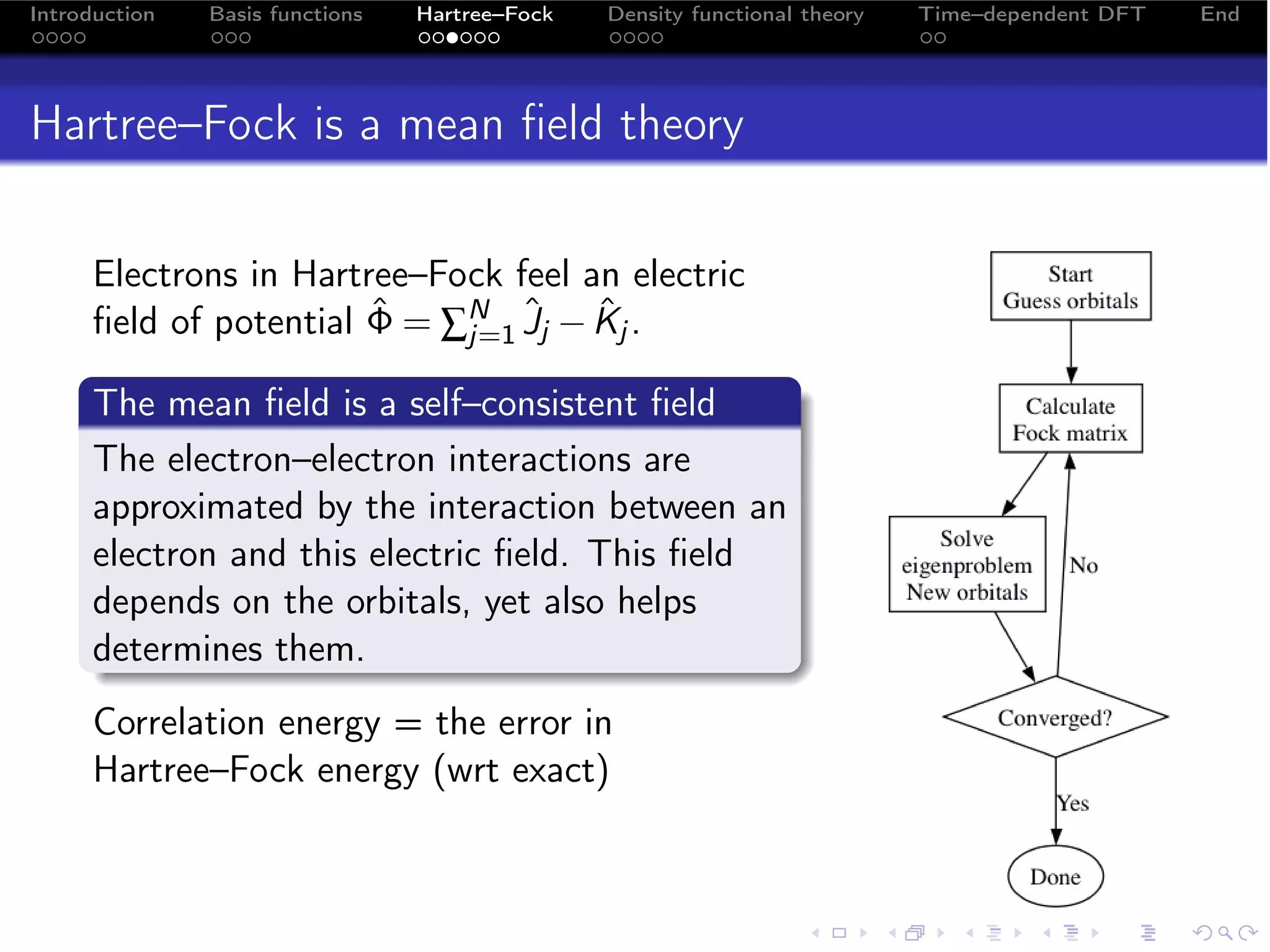

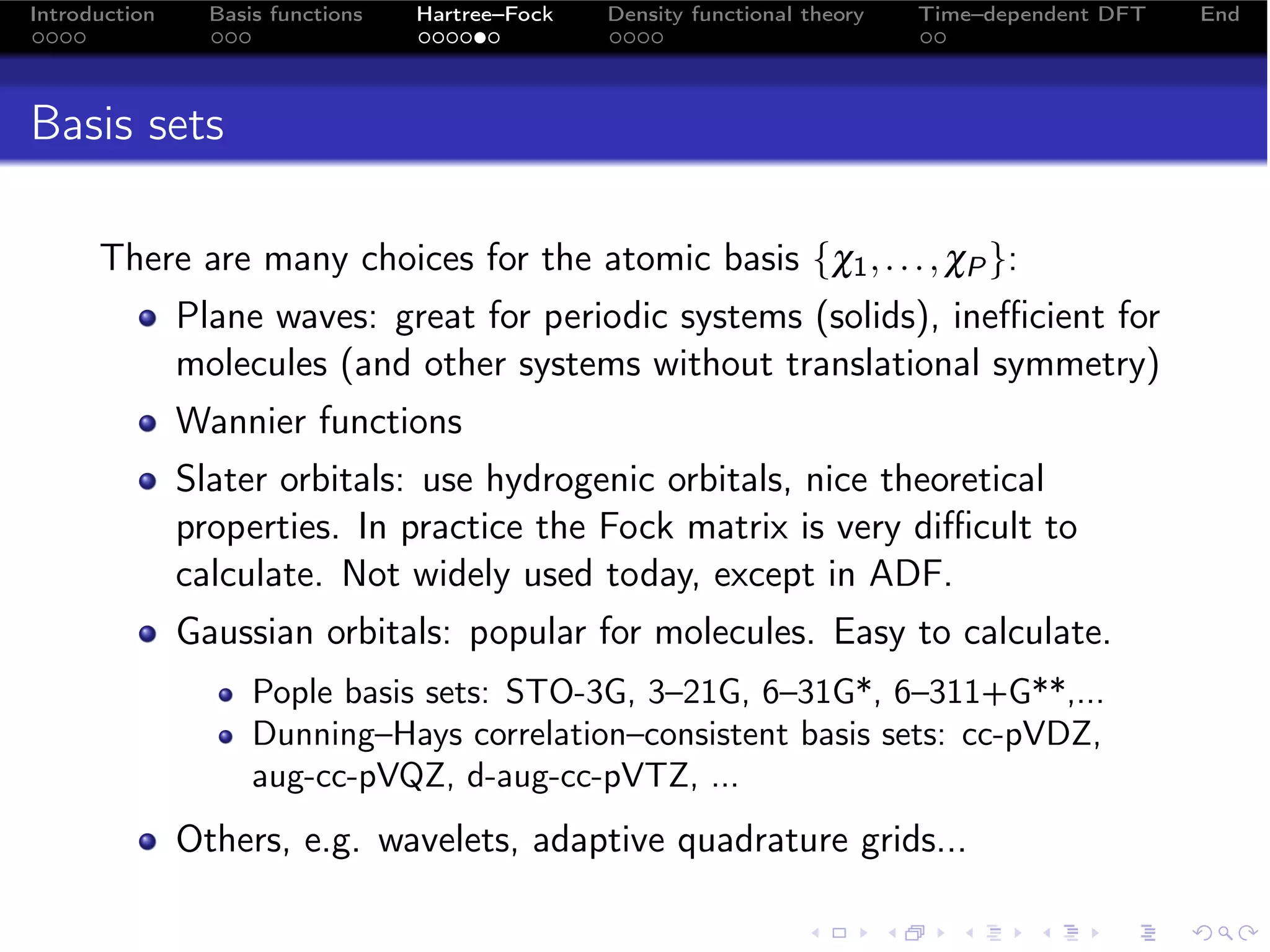

Density functionals

The form of the exchange–correlation functional Exc is unknown.

There are many, many approximations to it:

“Jacob’s Ladder” of approximations to Exc [ρ]:5

1 Exc [ρ] LDA X α, LDA,...

2 Exc [ρ, ∇ρ] GGA BLYP, PBE, PW91...

3 Exc [ρ, ∇ρ, τ] meta–GGA VSXC, TPSS, ...

4 Exc [ρ, ∇ρ, τ, {φ }o ] hybrids 6 ,... B3LYP, PBE0,...

5 Exc [ρ, ∇ρ, τ, {φ }] fully nonlocal -

LDA, local density approximation; GGA, generalized gradient

approximation; τ, kinetic energy density; {φ }o , occupied

orbitals; {φ }, all orbitals.

Green function expansions for Exc : GW, Görling–Levy PT,...

Approximations to kinetic energy: Thomas–Fermi, von

Wiezsäcker,...

5 M. Casida, http://bit.ly/casidadft

6 Hybrid functionals mix in Hartree–Fock exchange.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/efrc-lunch-100311234948-phpapp01/75/A-brief-introduction-to-Hartree-Fock-and-TDDFT-20-2048.jpg)