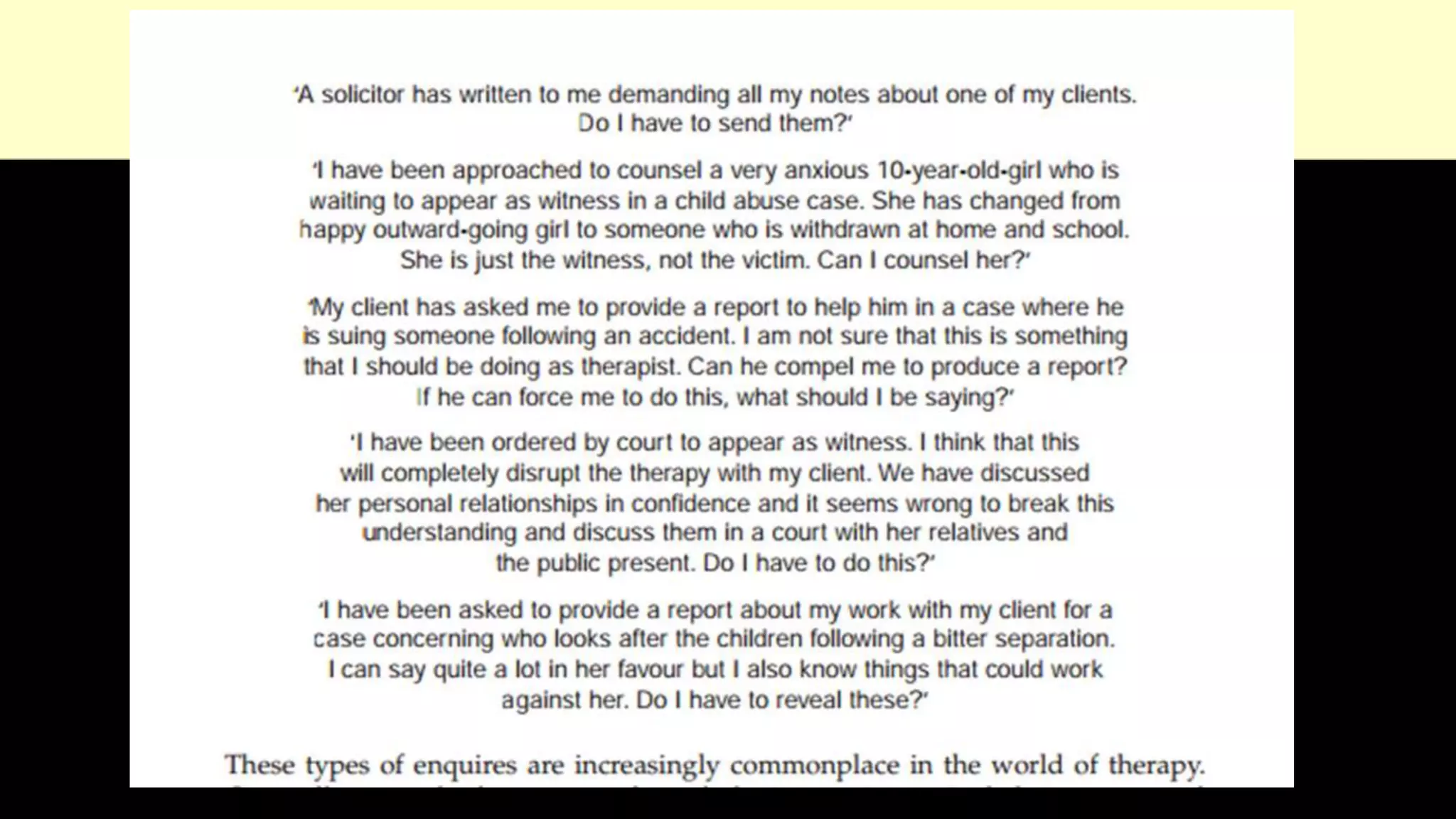

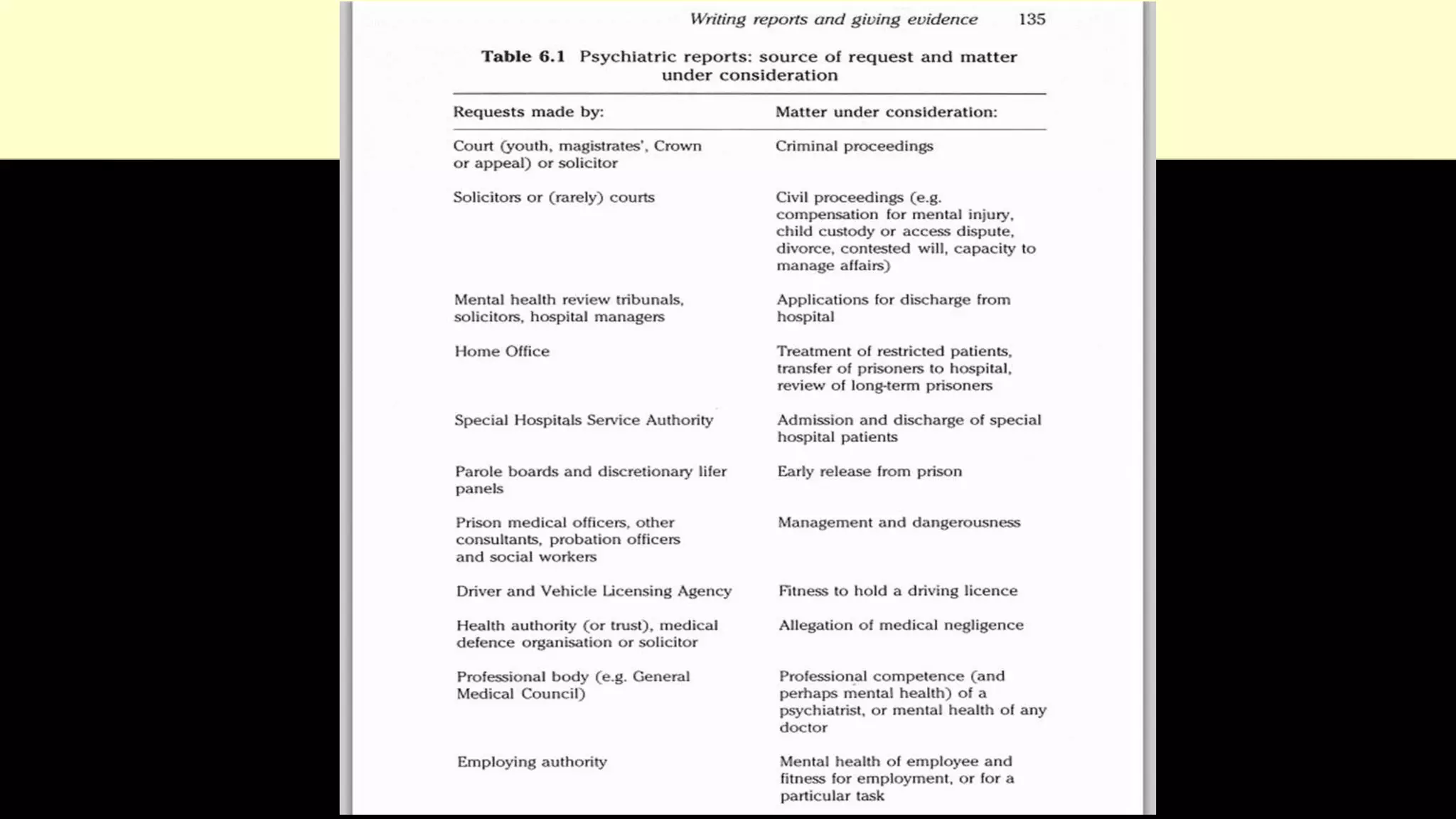

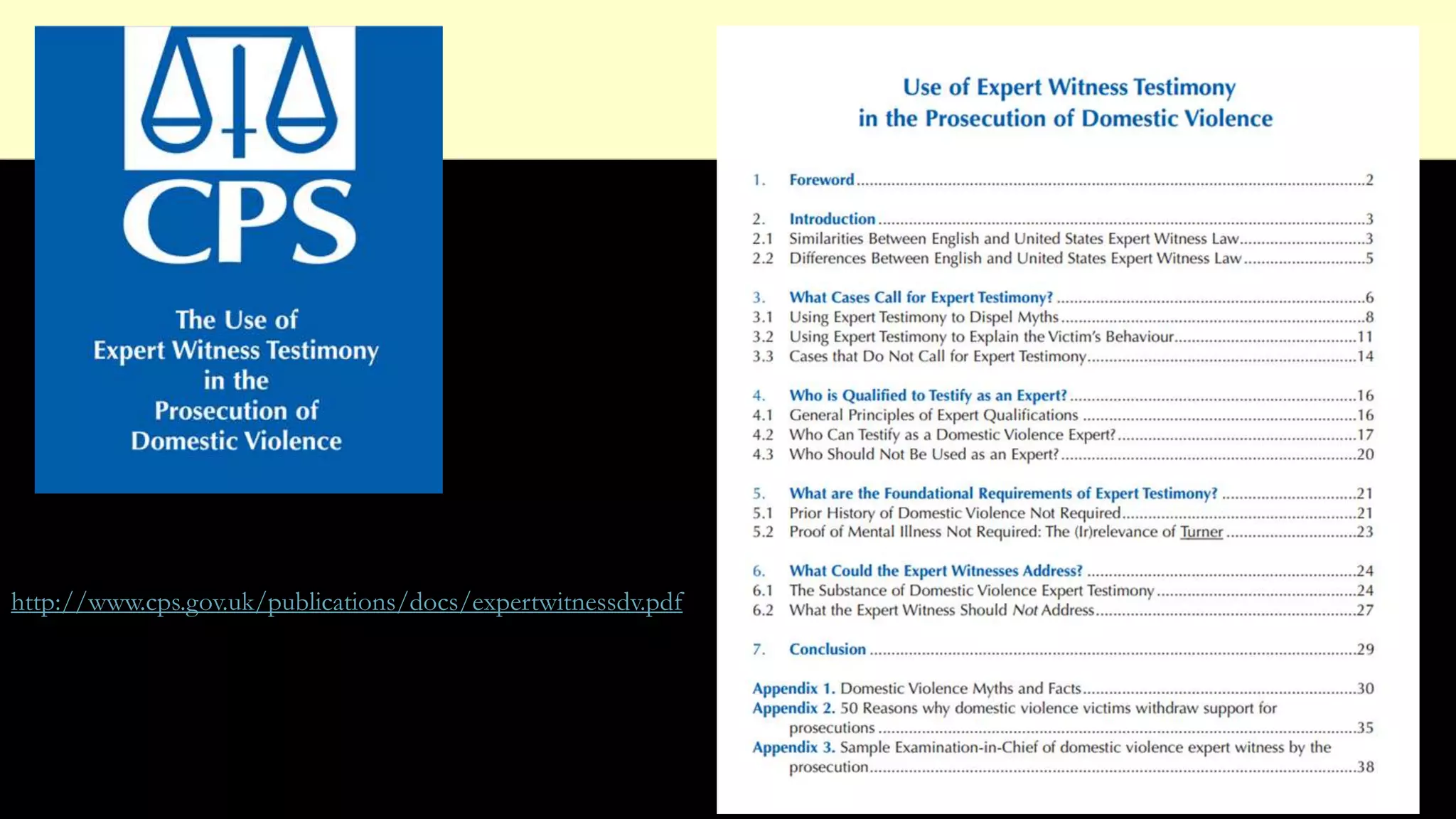

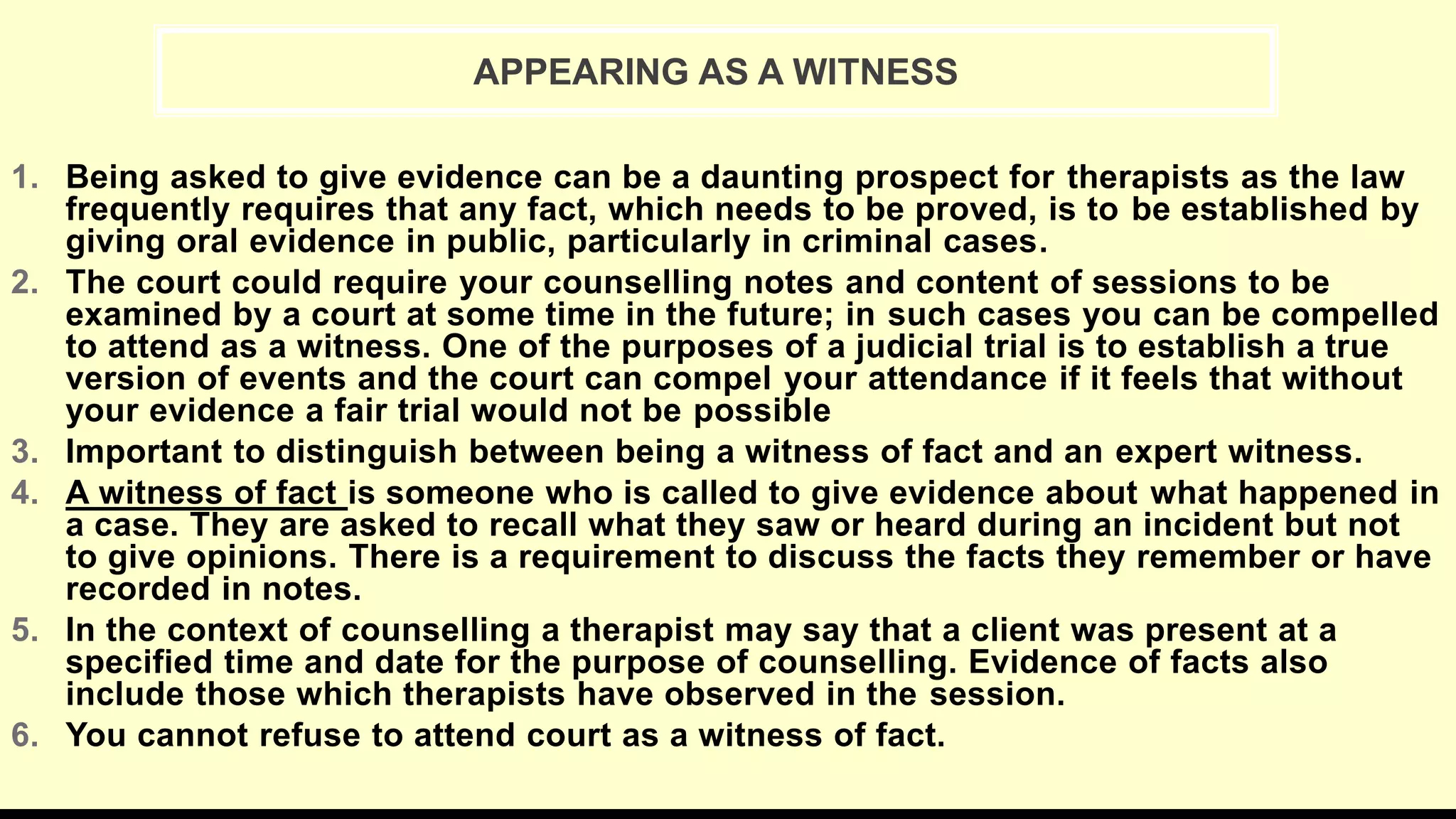

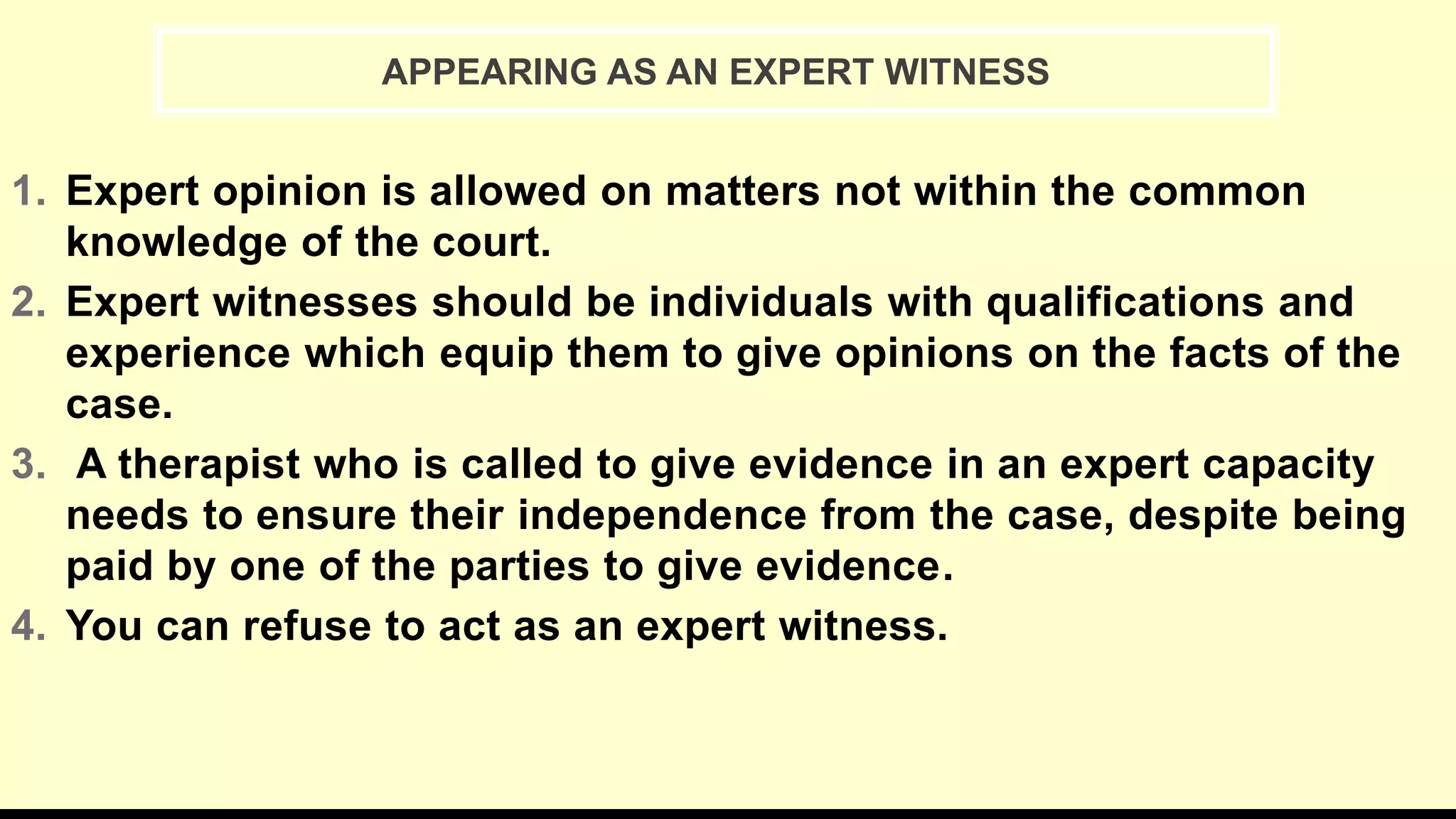

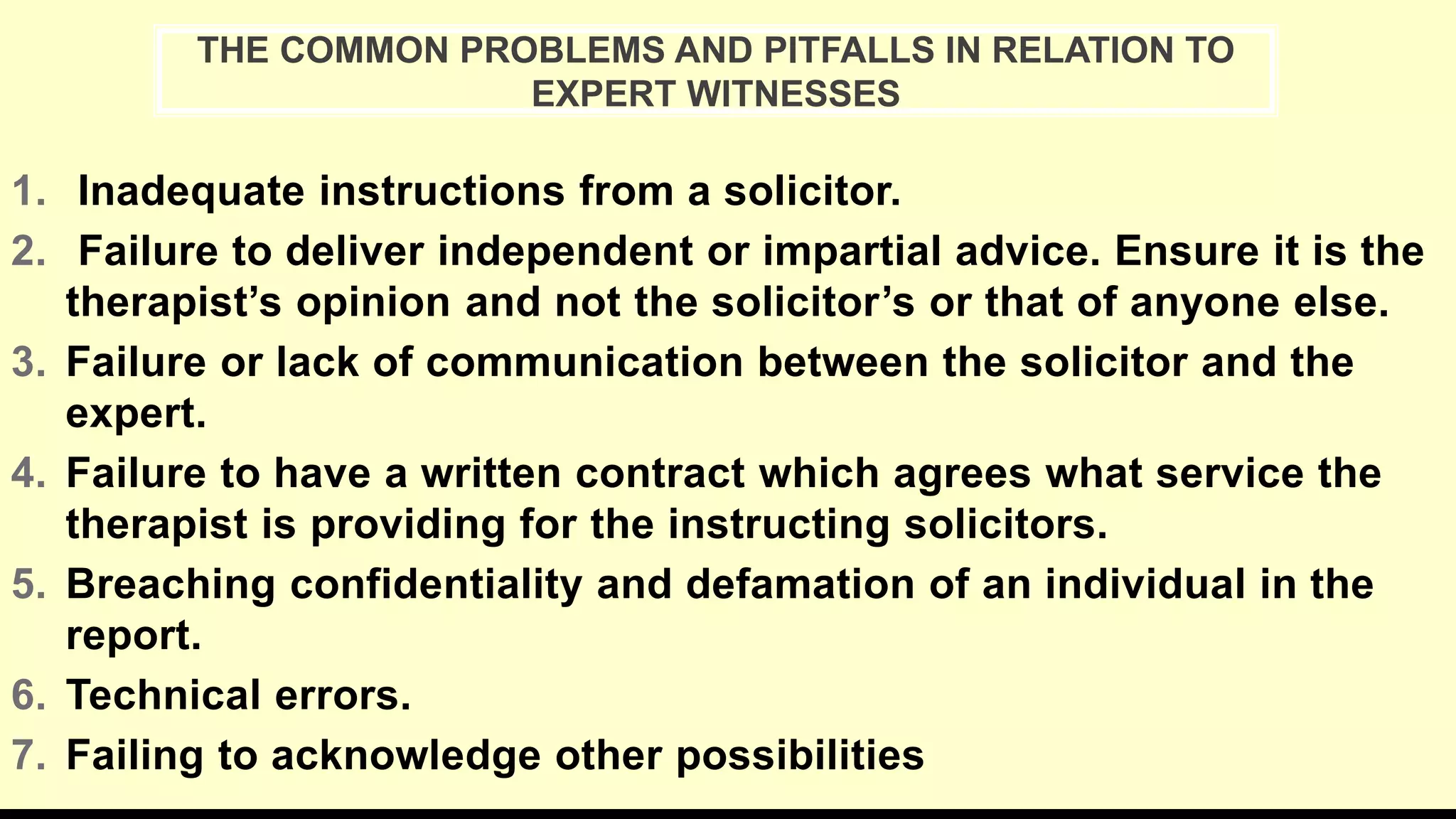

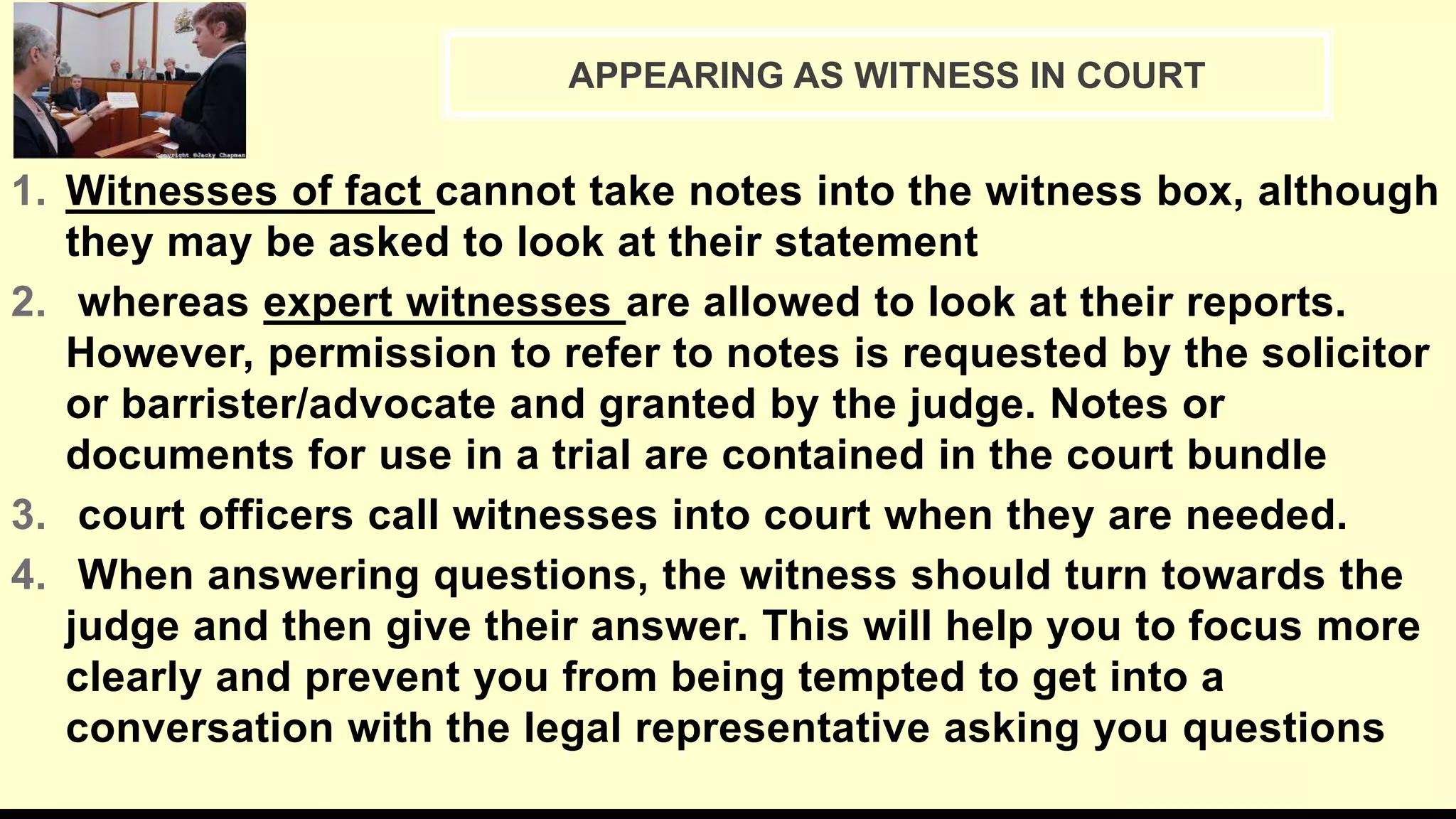

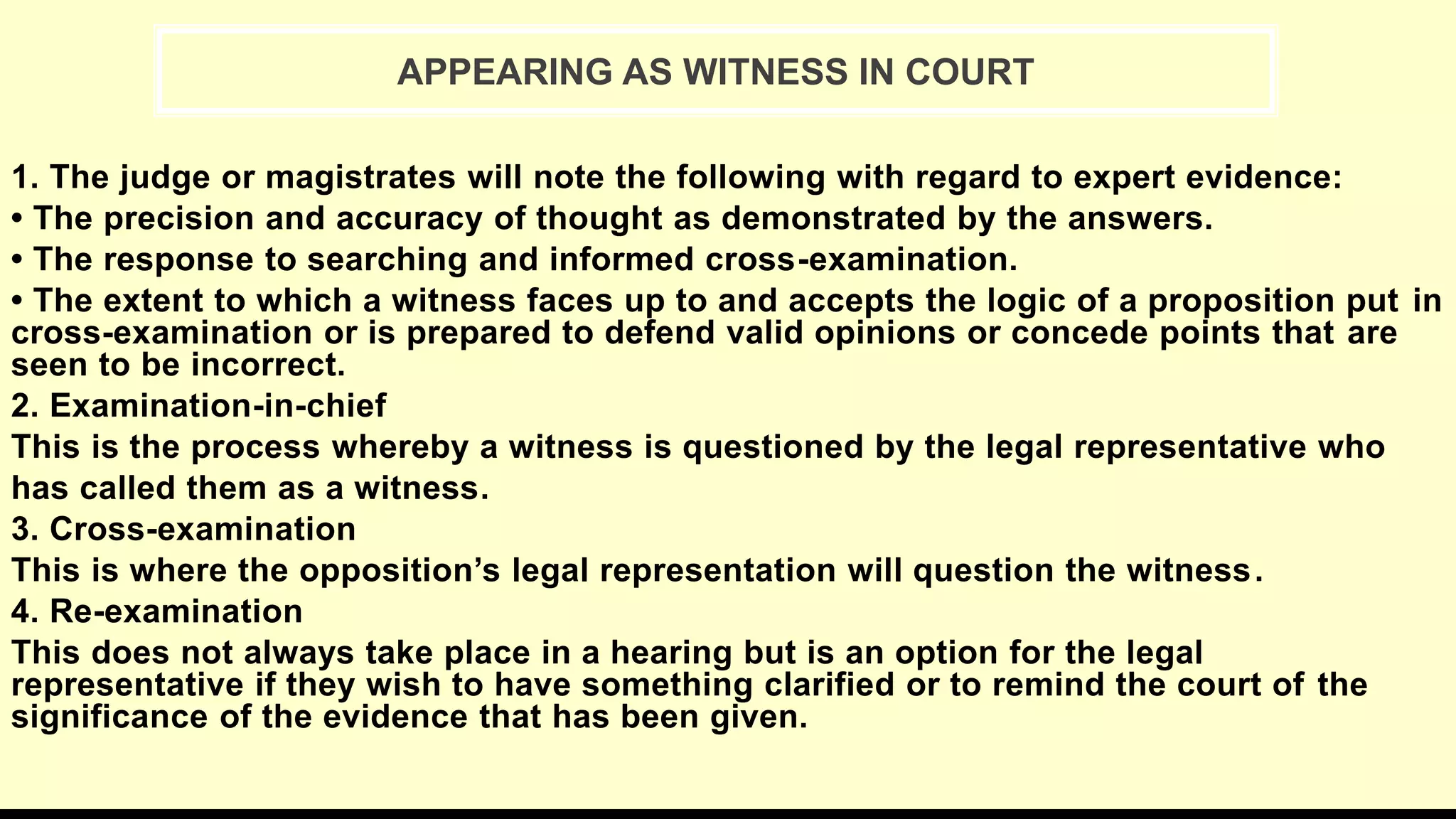

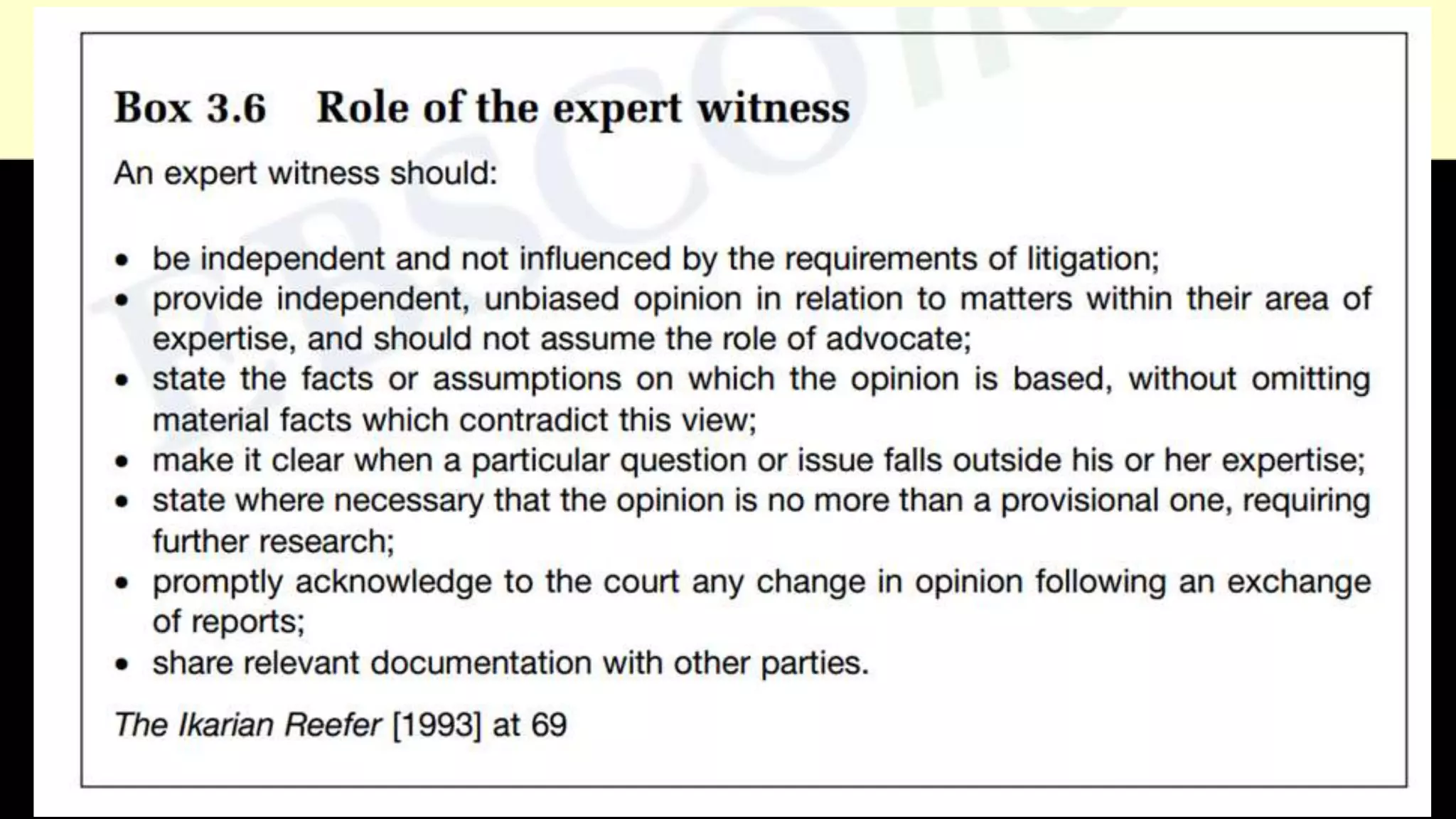

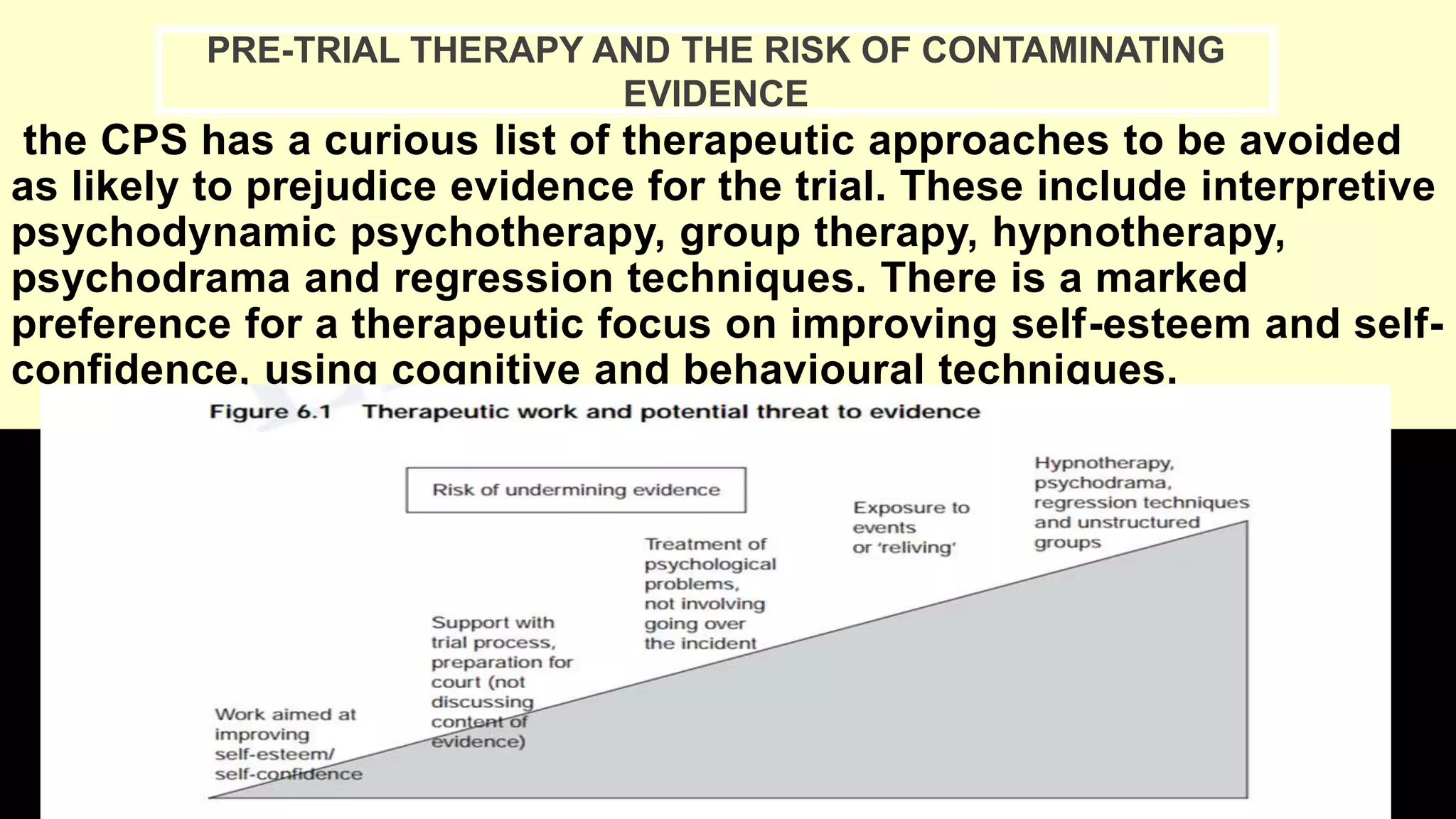

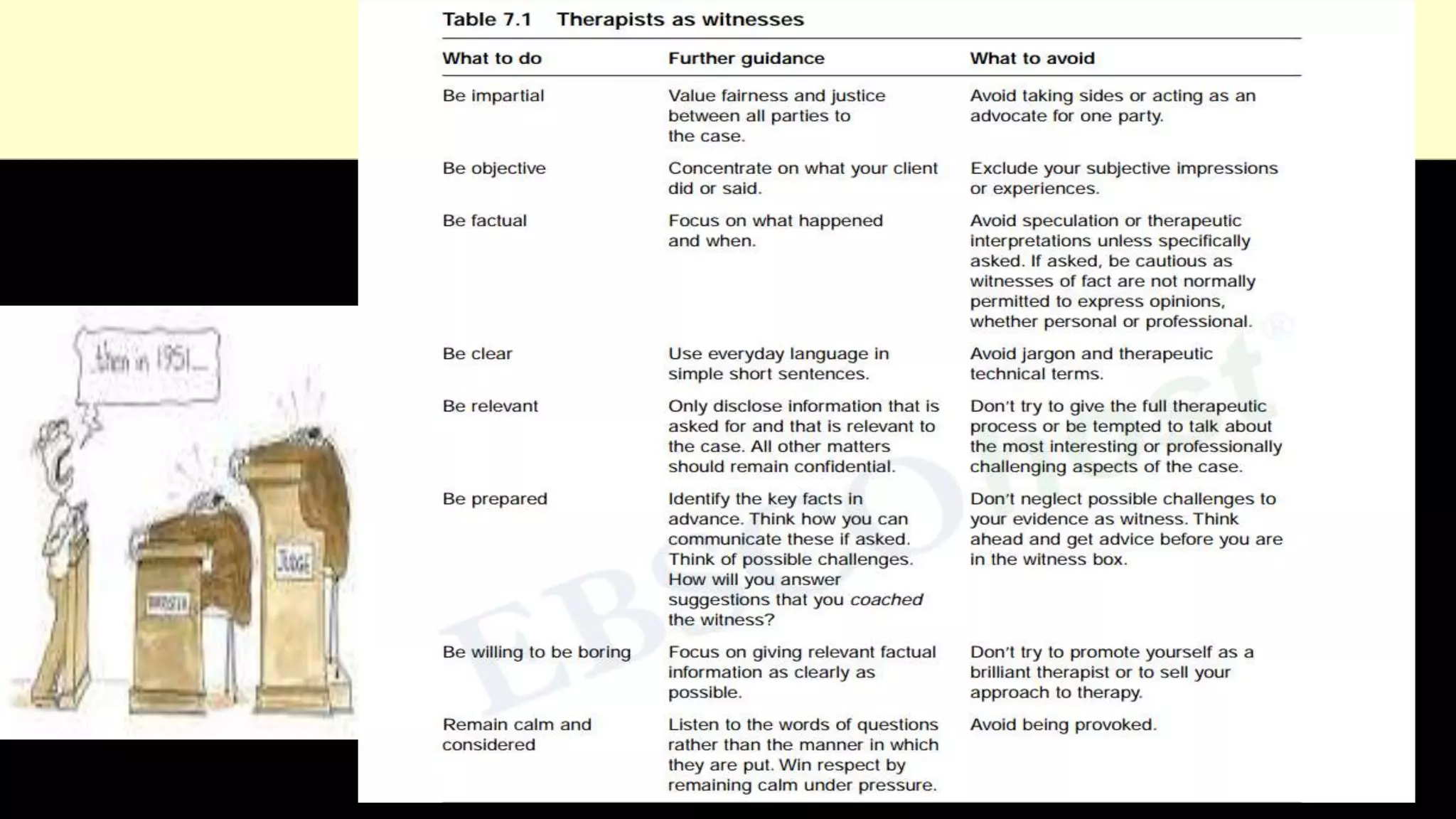

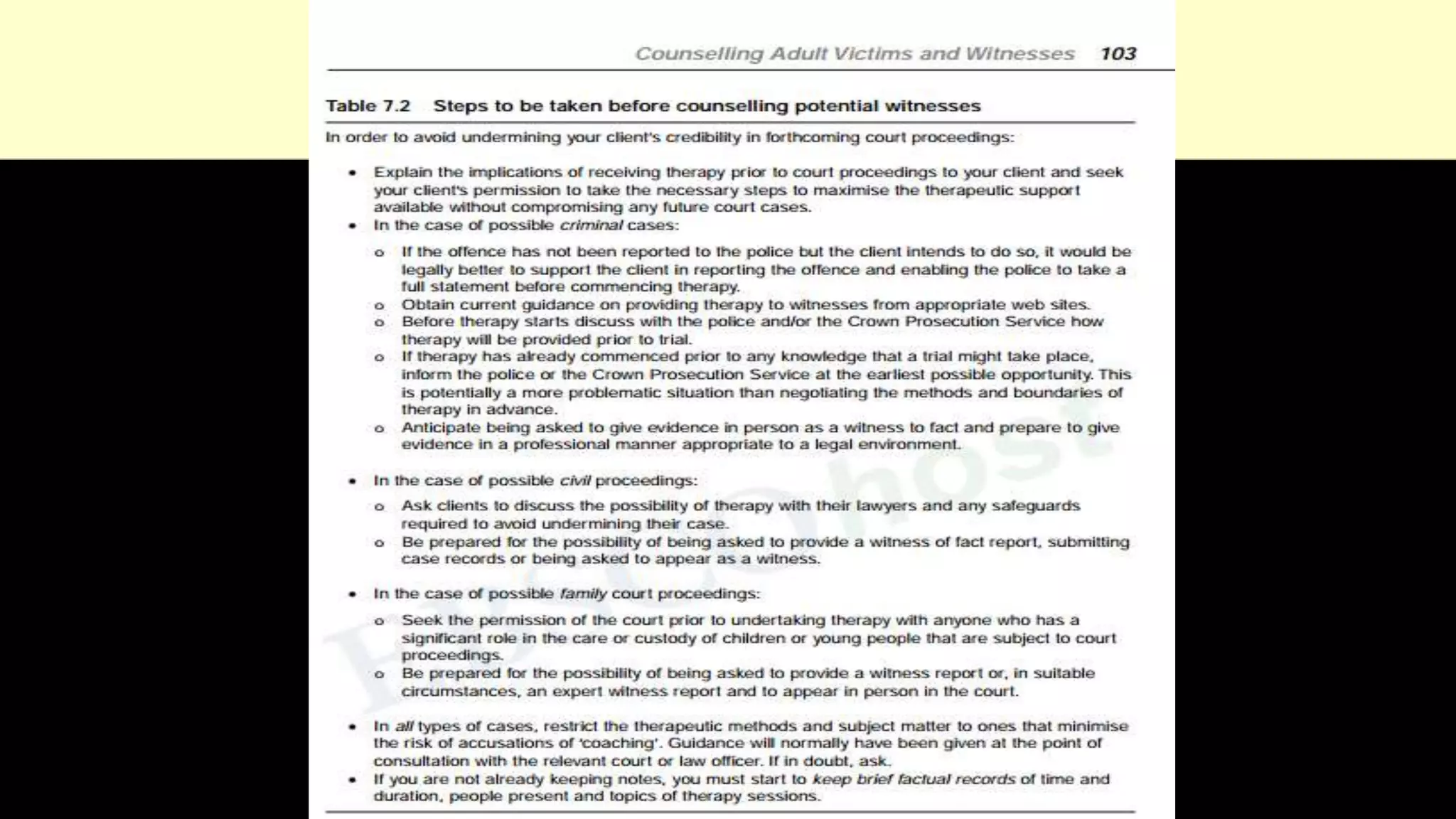

Therapists may become involved with the legal system in a number of ways such as providing therapy for clients involved in legal proceedings or being called as an expert witness. When writing reports for the legal system, therapists must remain impartial and concise. They should only include fact-based information relevant to the legal matter. If called as a witness, therapists must distinguish between providing facts or expert opinions. Overall, therapists must balance the needs of clients with their responsibilities to the court.