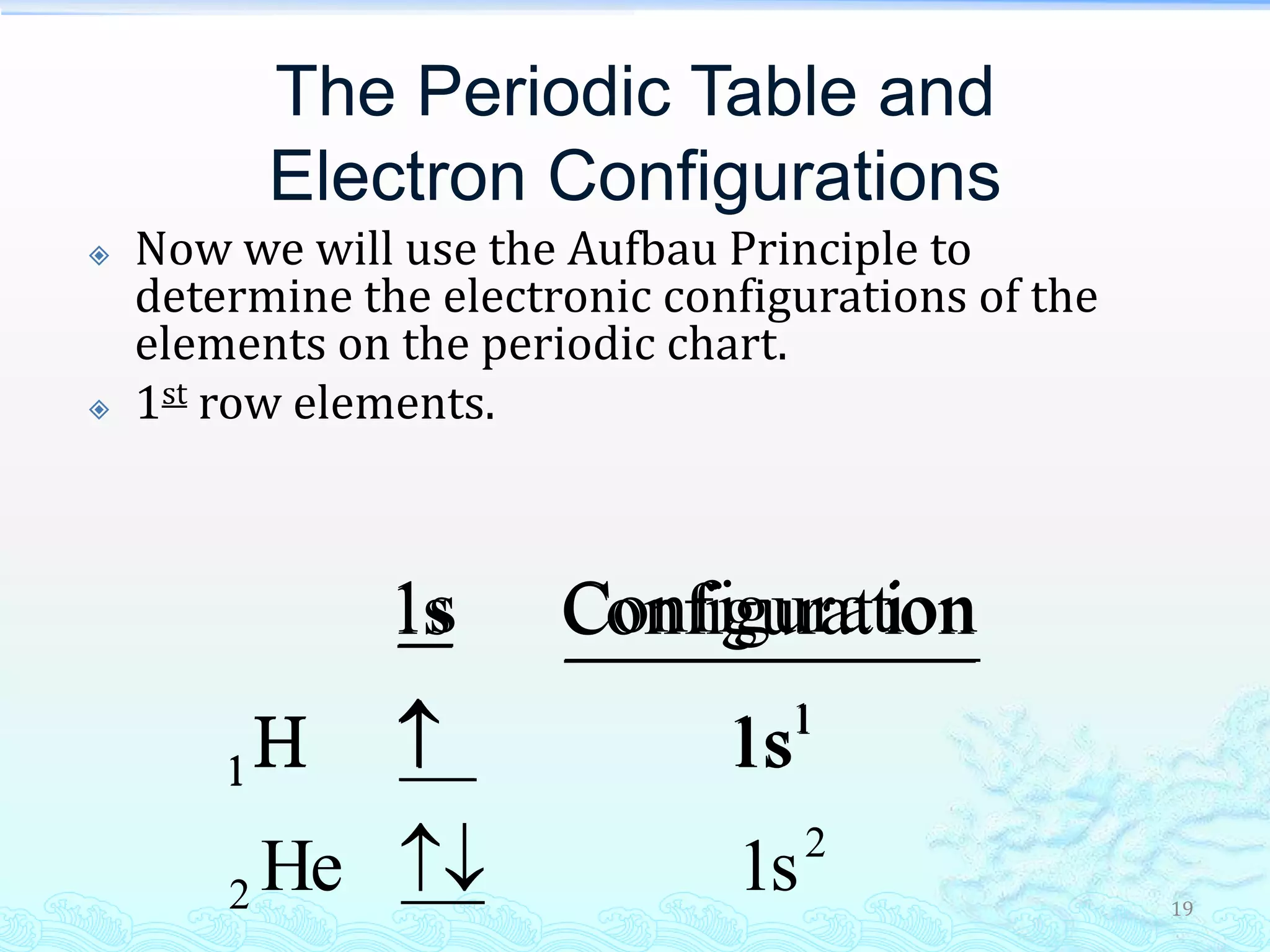

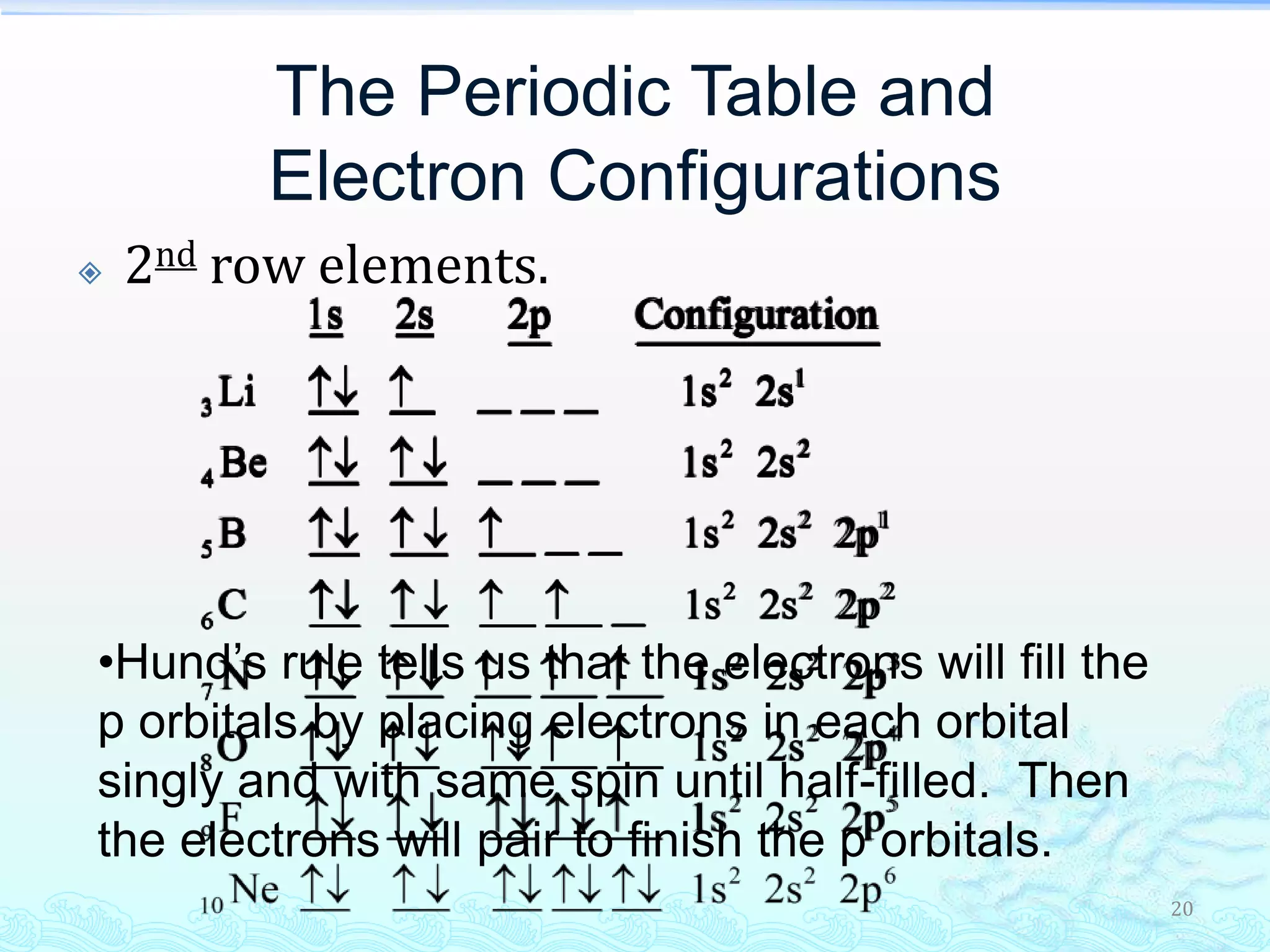

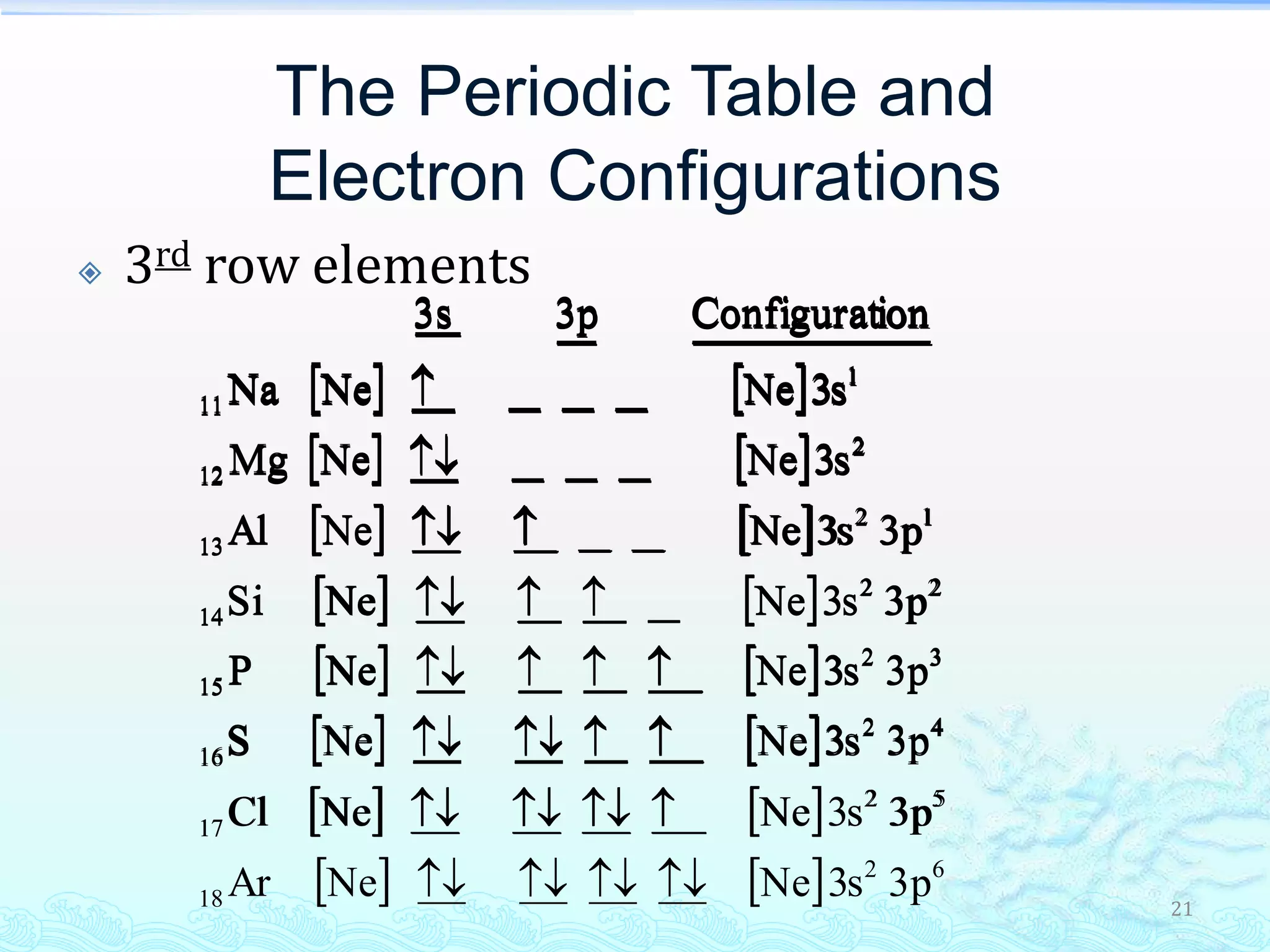

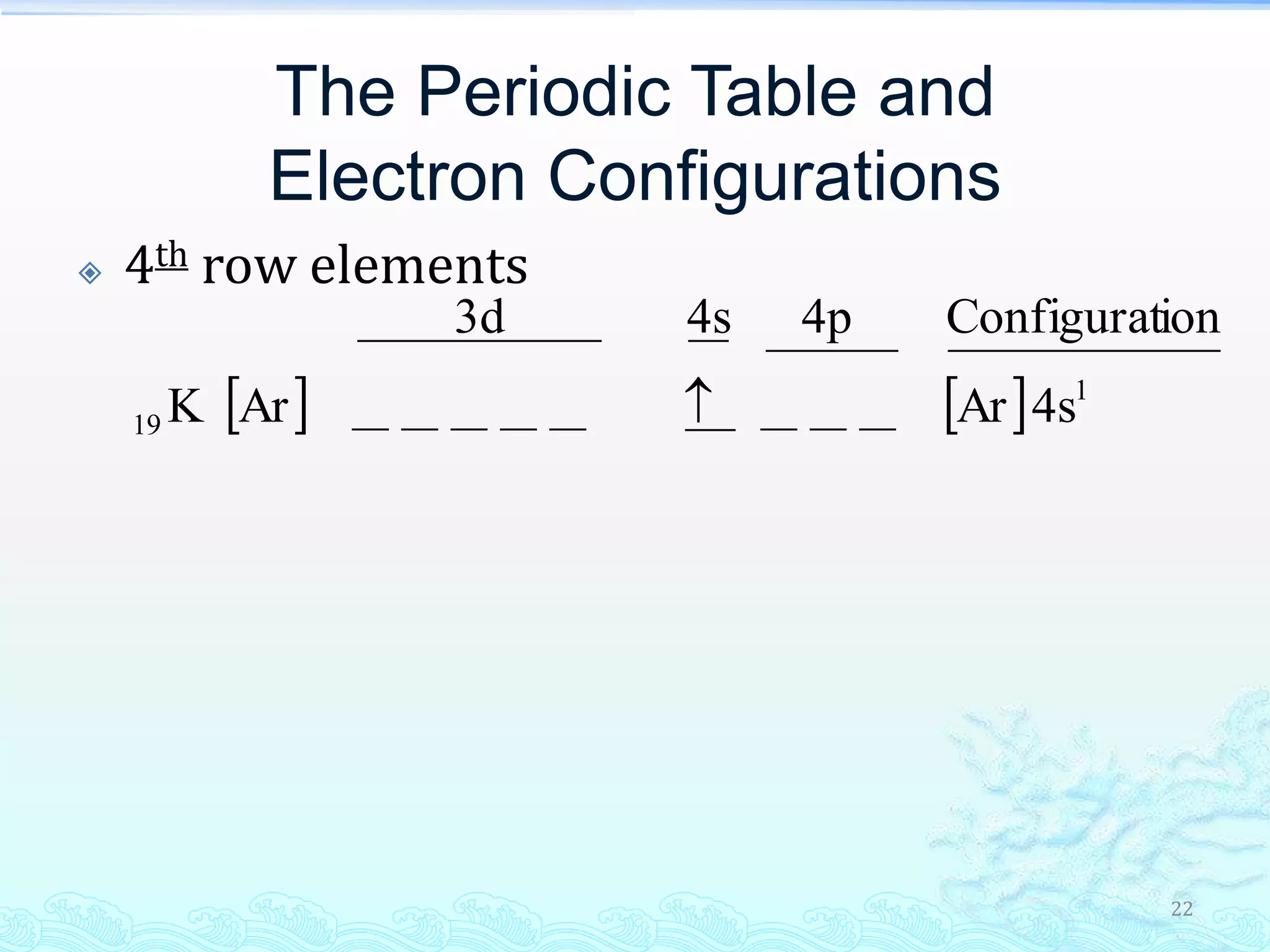

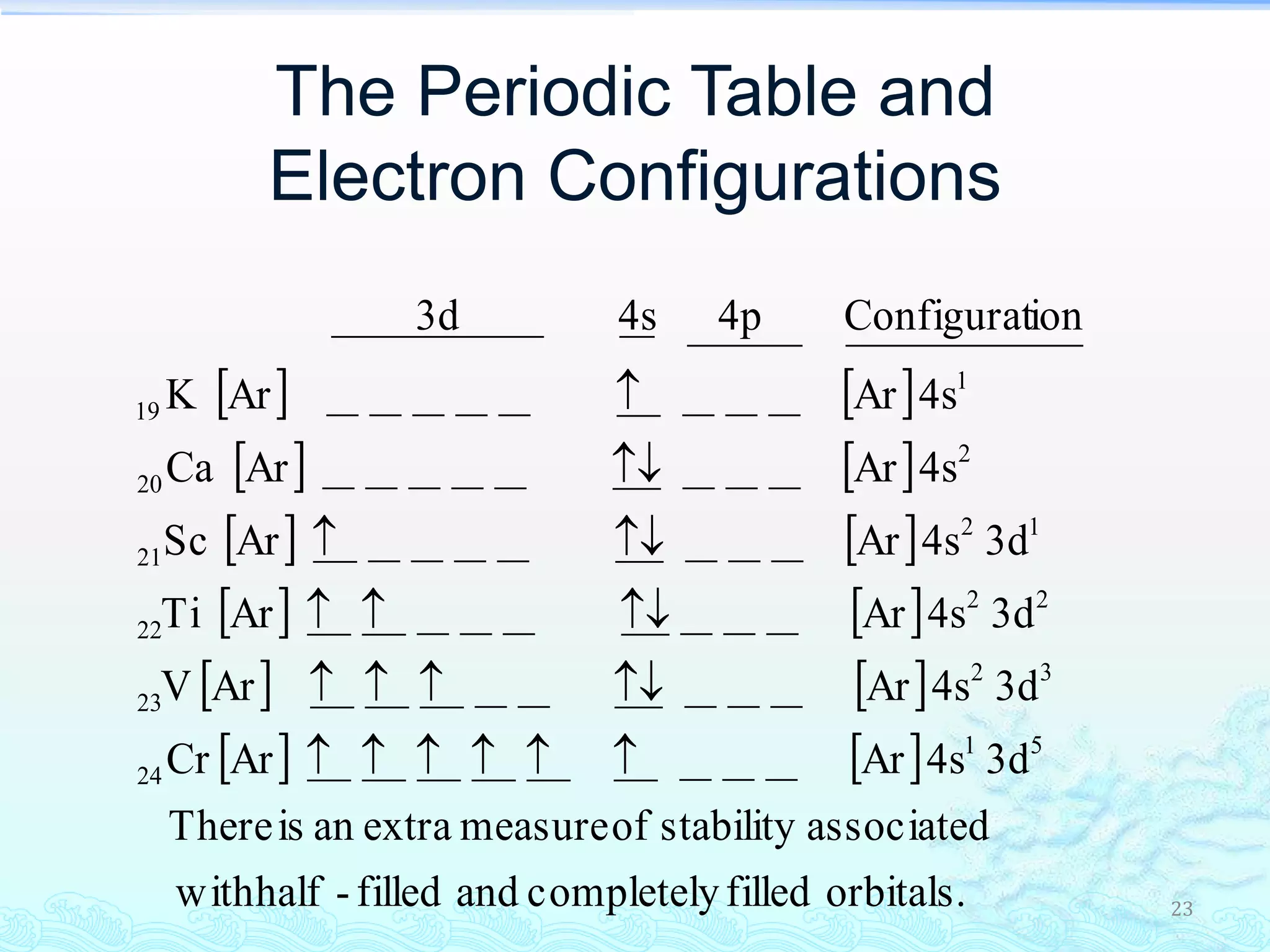

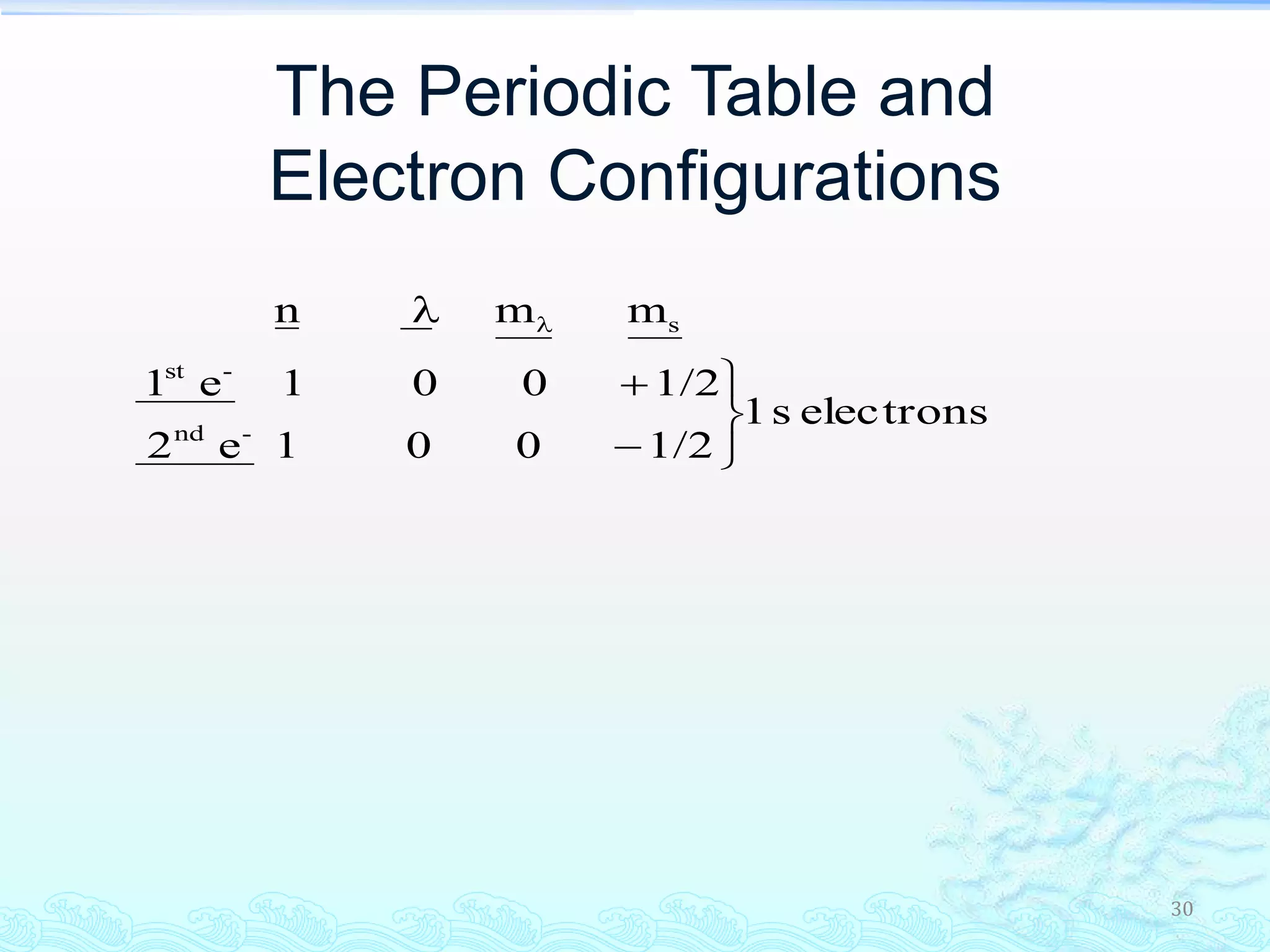

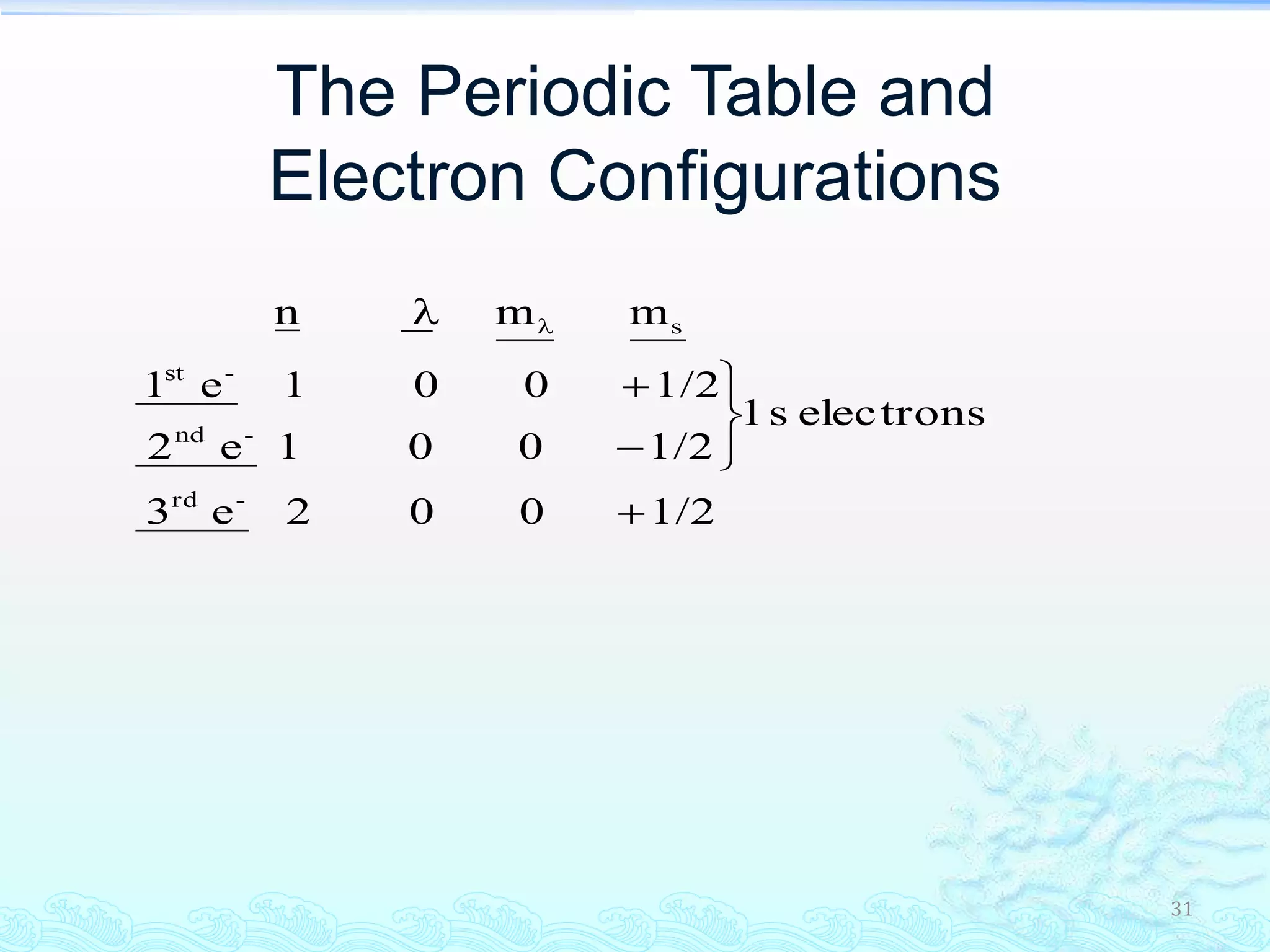

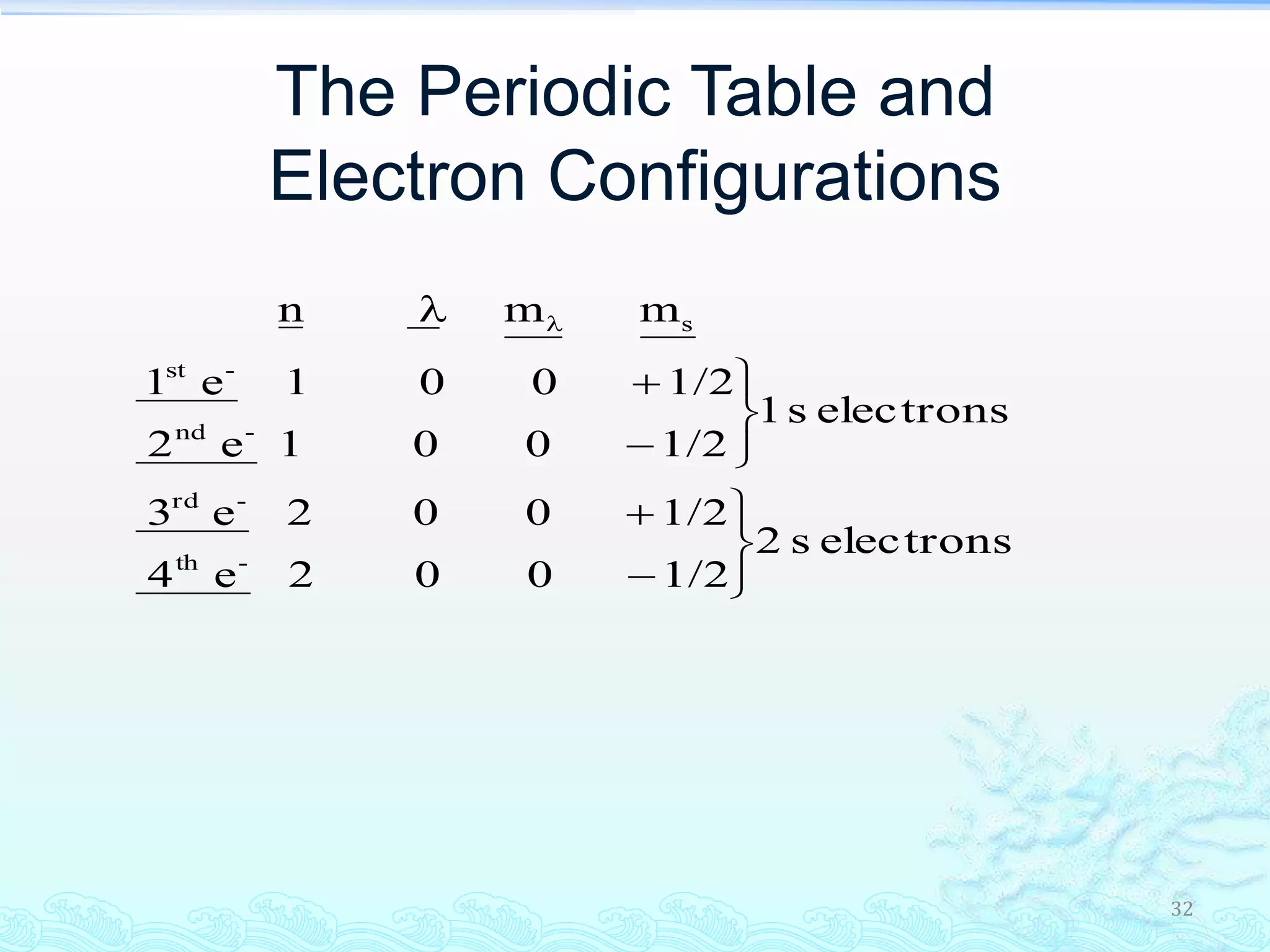

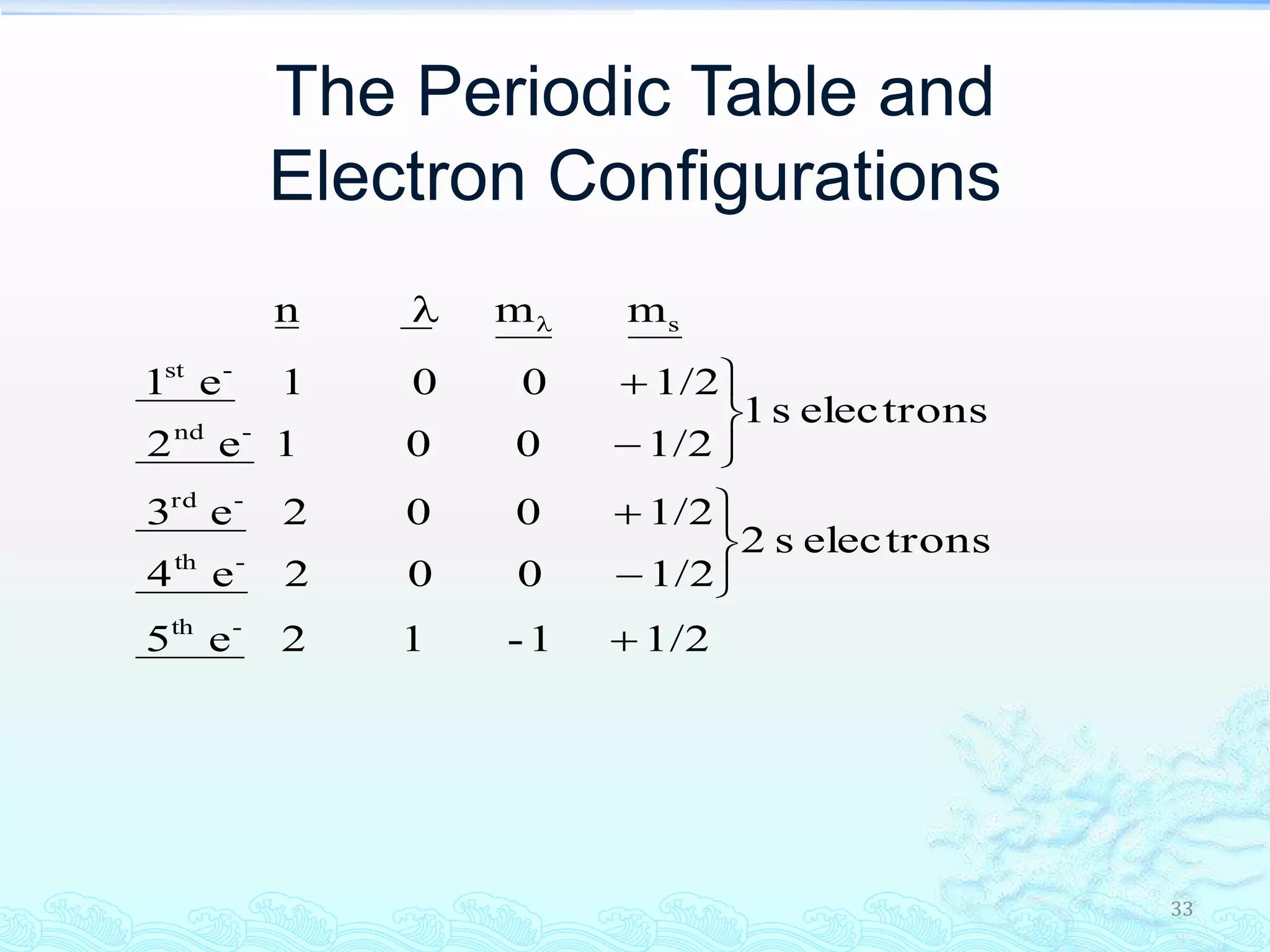

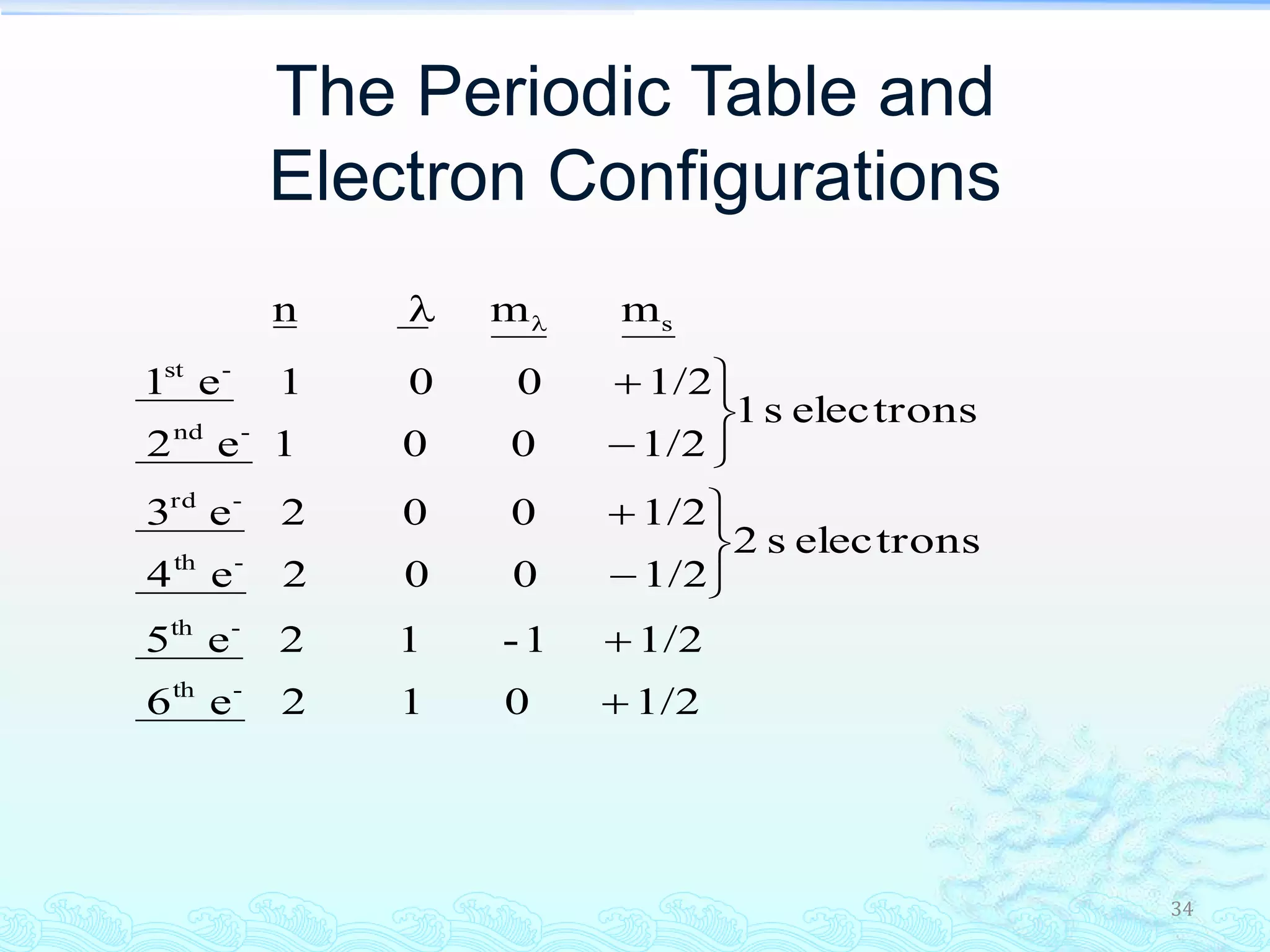

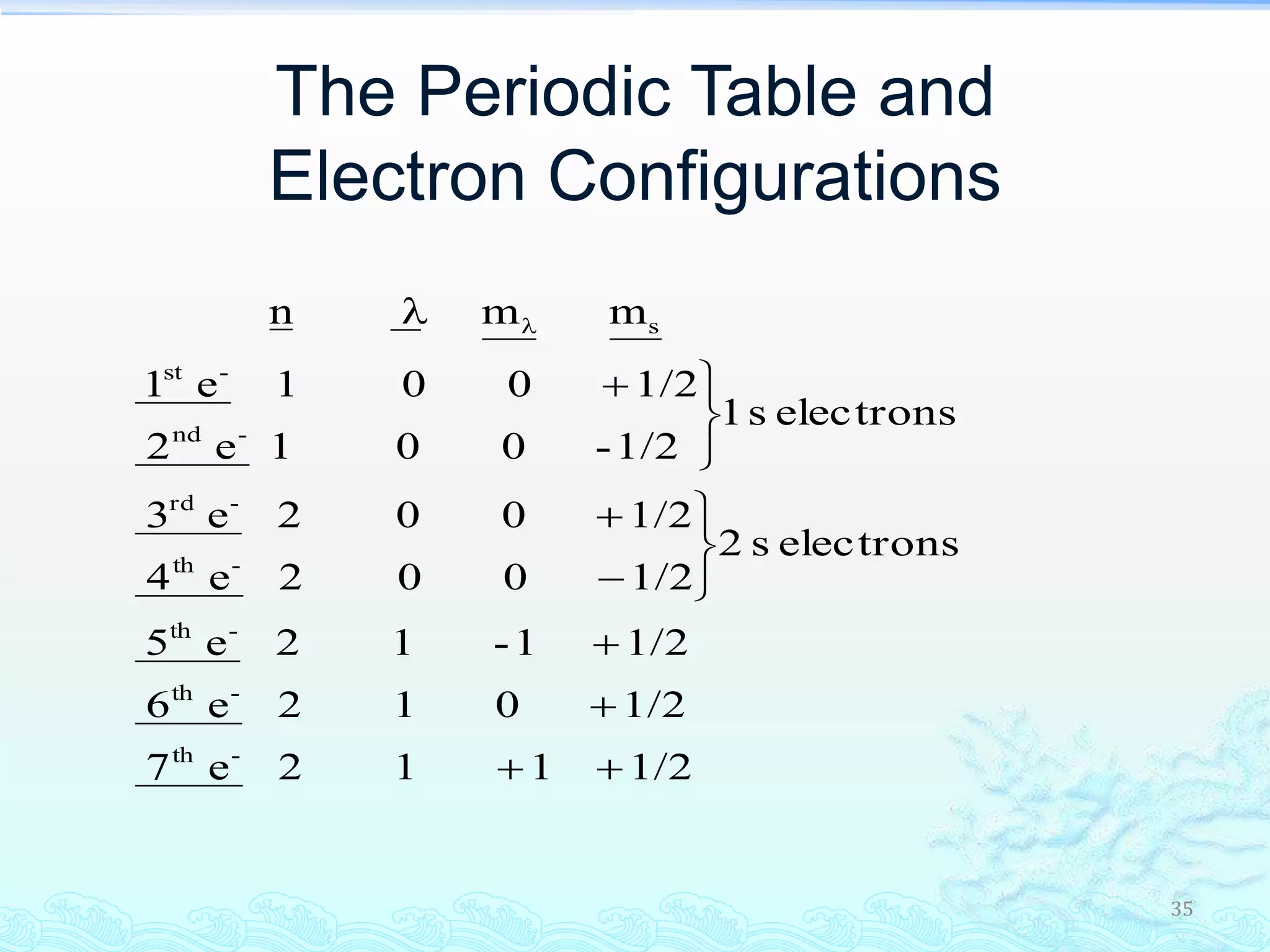

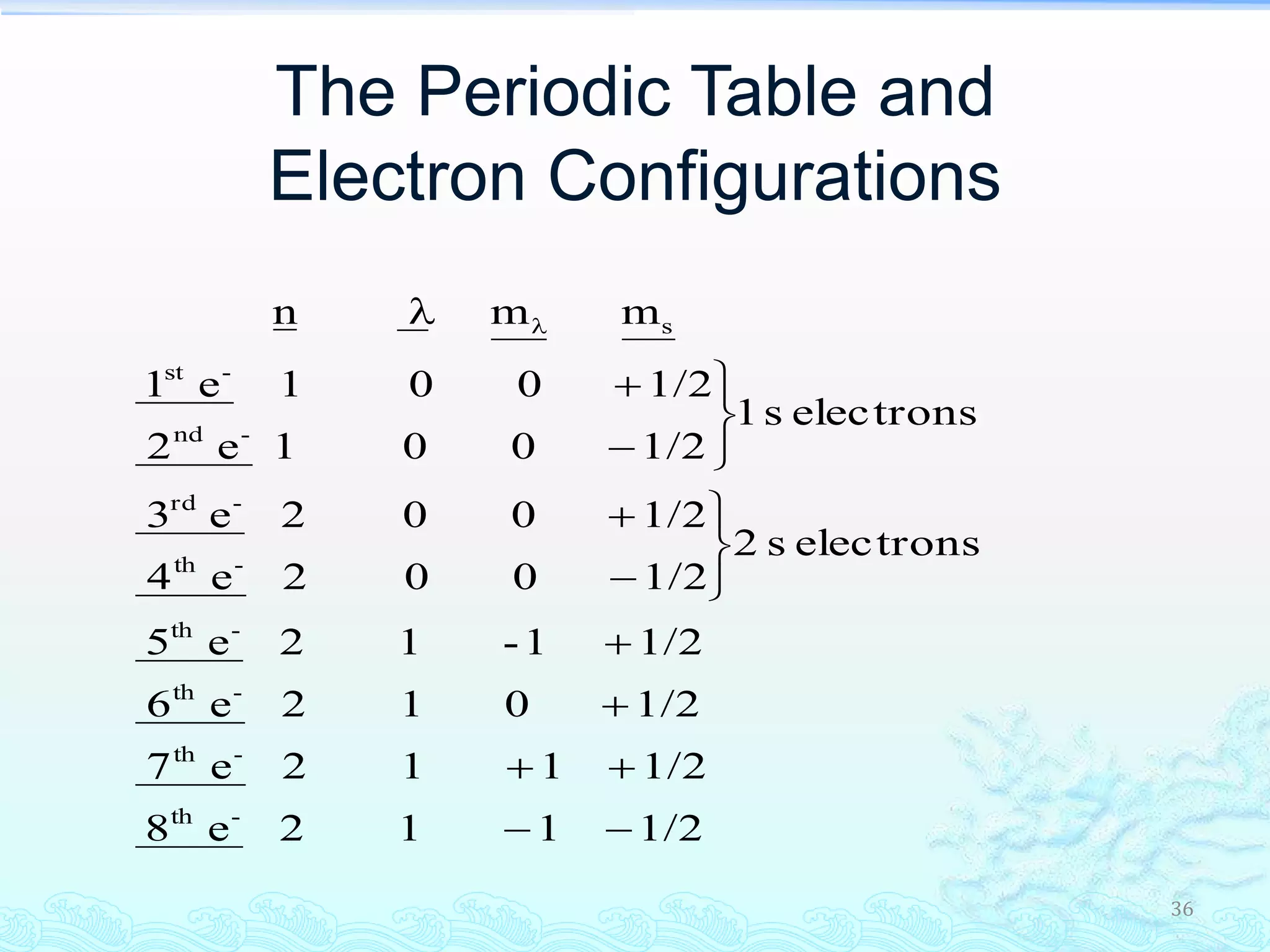

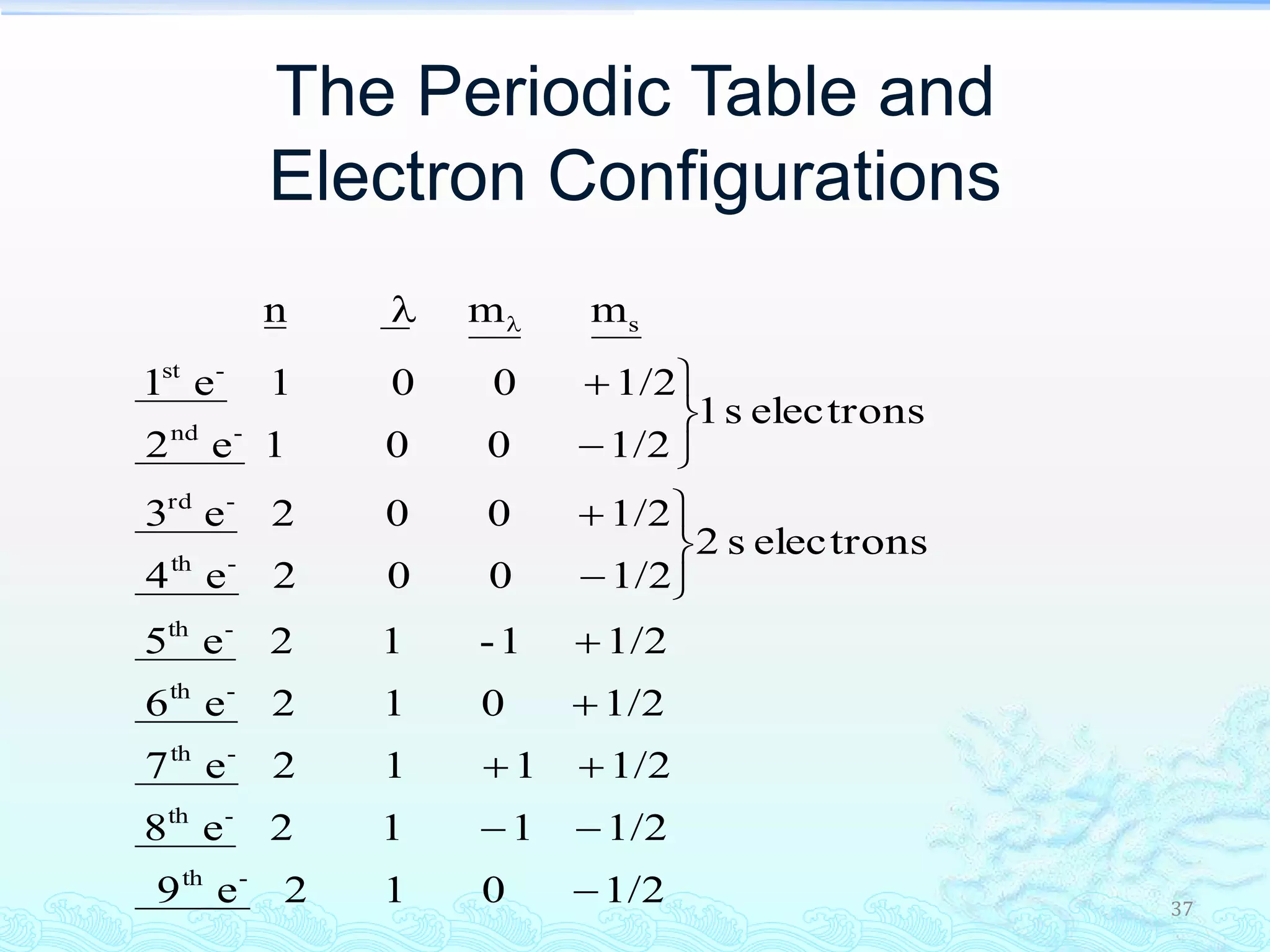

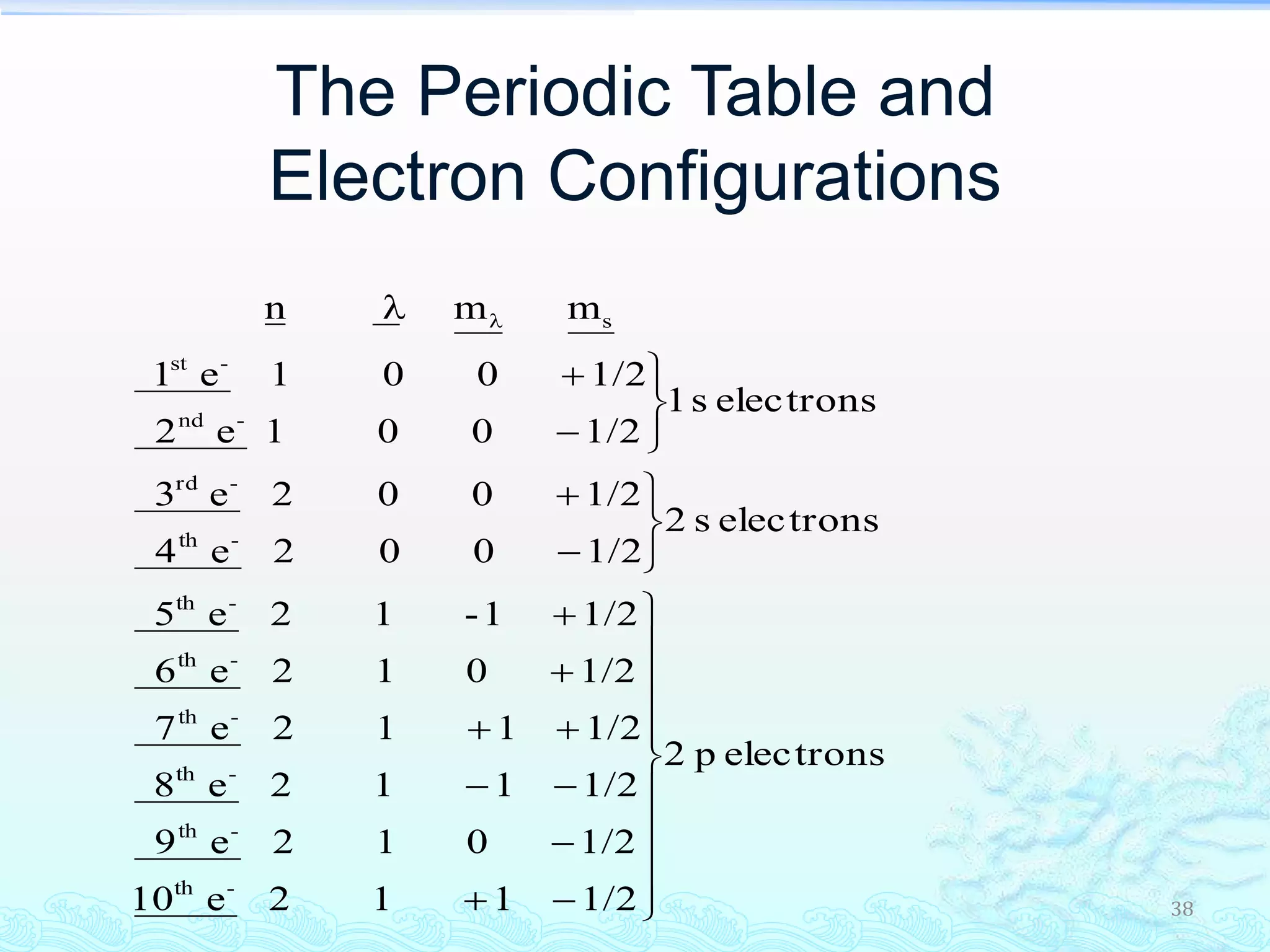

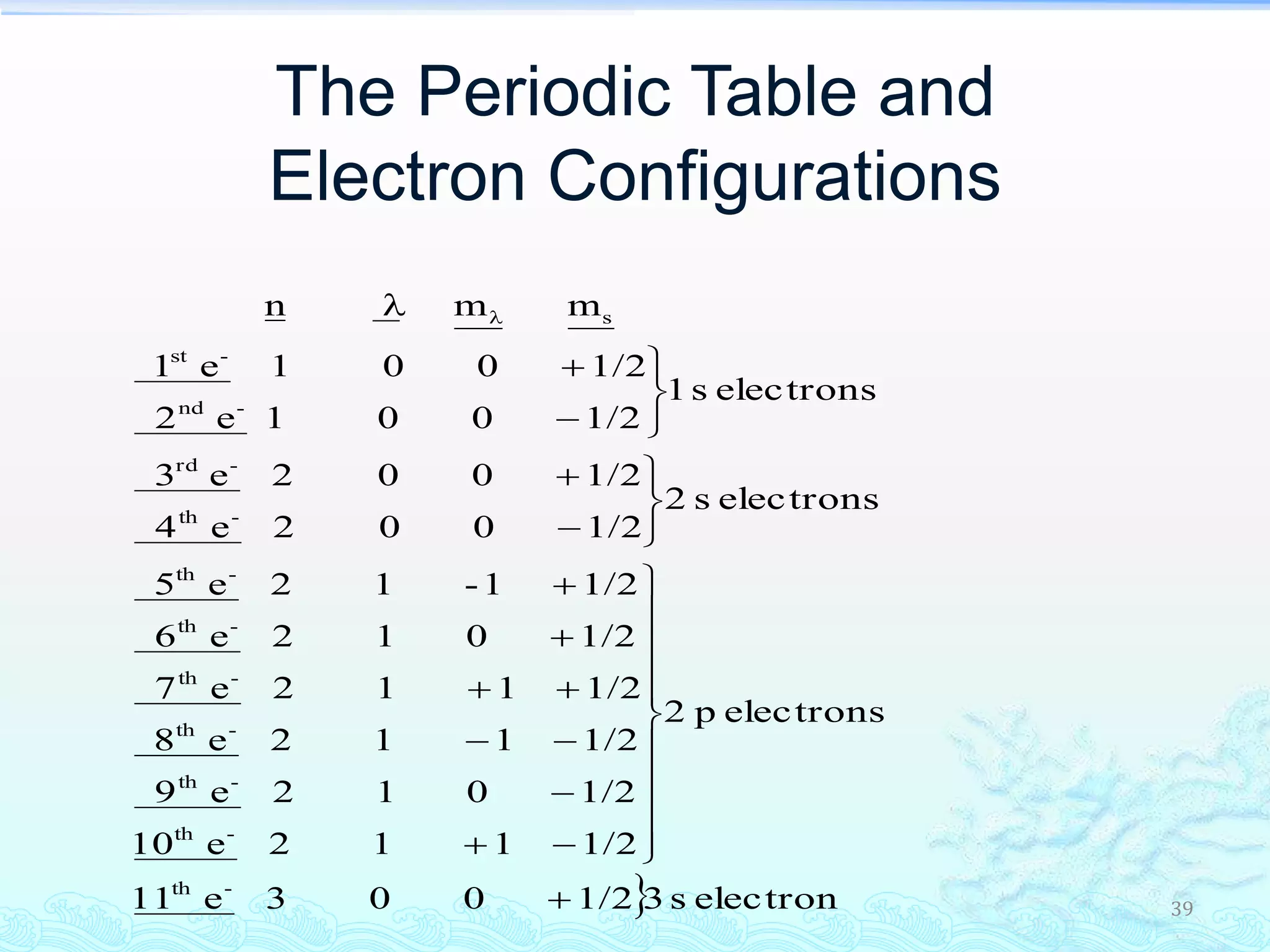

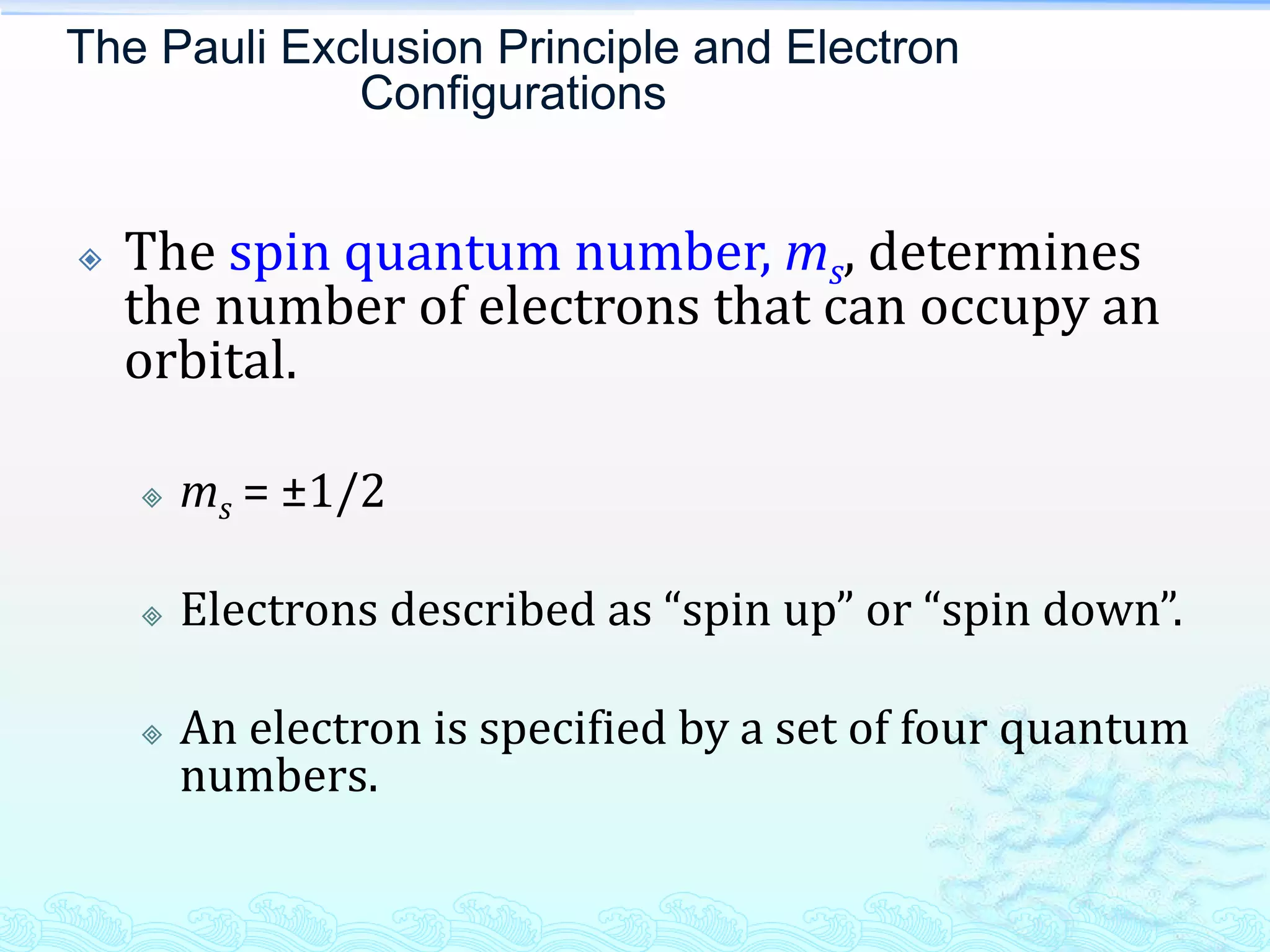

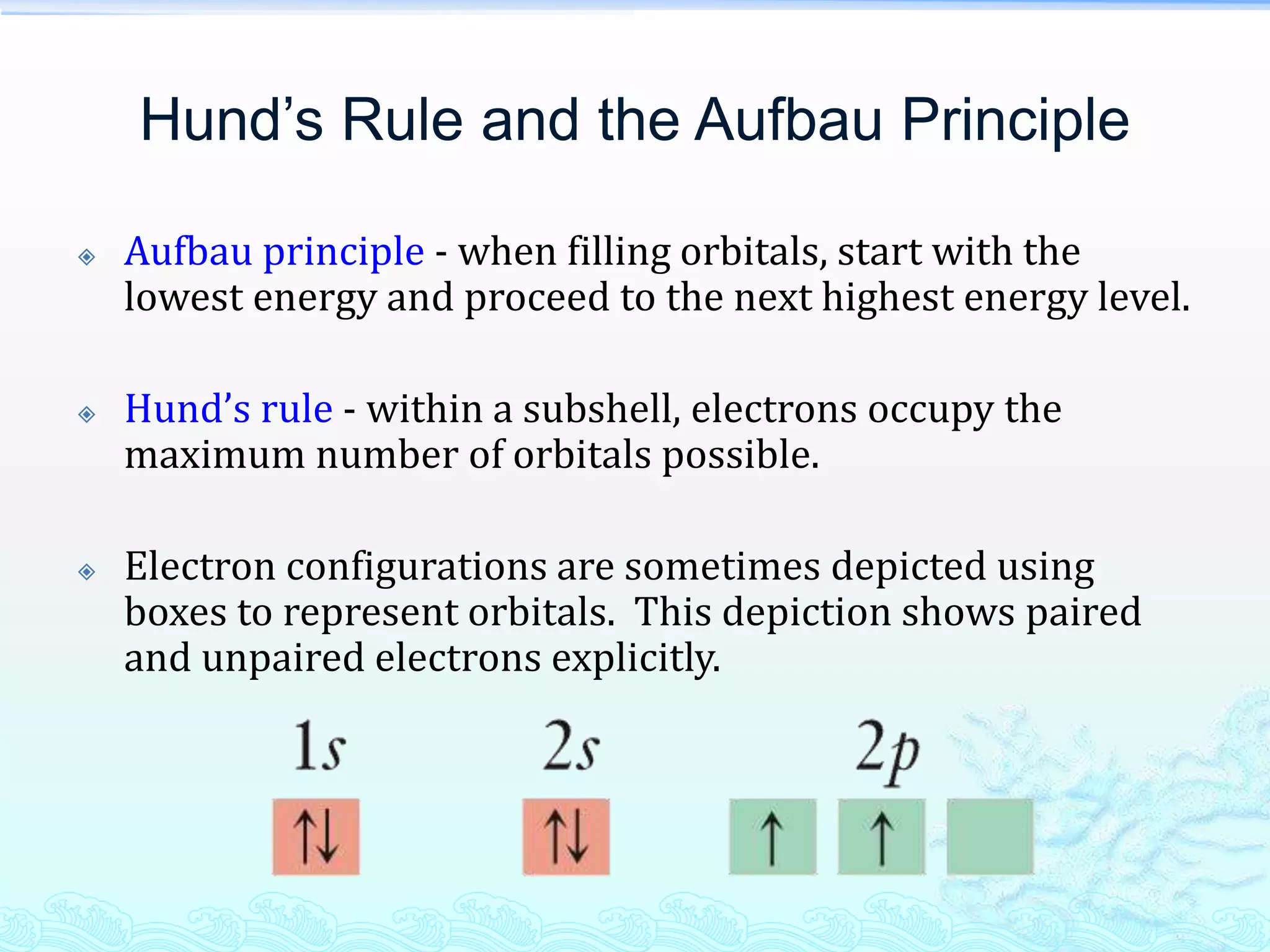

The document discusses electron configurations and the Pauli Exclusion Principle. It explains that electrons are described by four quantum numbers and that the Pauli Exclusion Principle states that no two electrons in an atom can have the same set of four quantum numbers. Orbital energies are determined by factors like orbital size and shielding effects. Electron configurations are written according to the Aufbau principle and Hund's rule, filling lower energy orbitals first with parallel spins when possible.

![Hund’s Rule and the Aufbau Principle

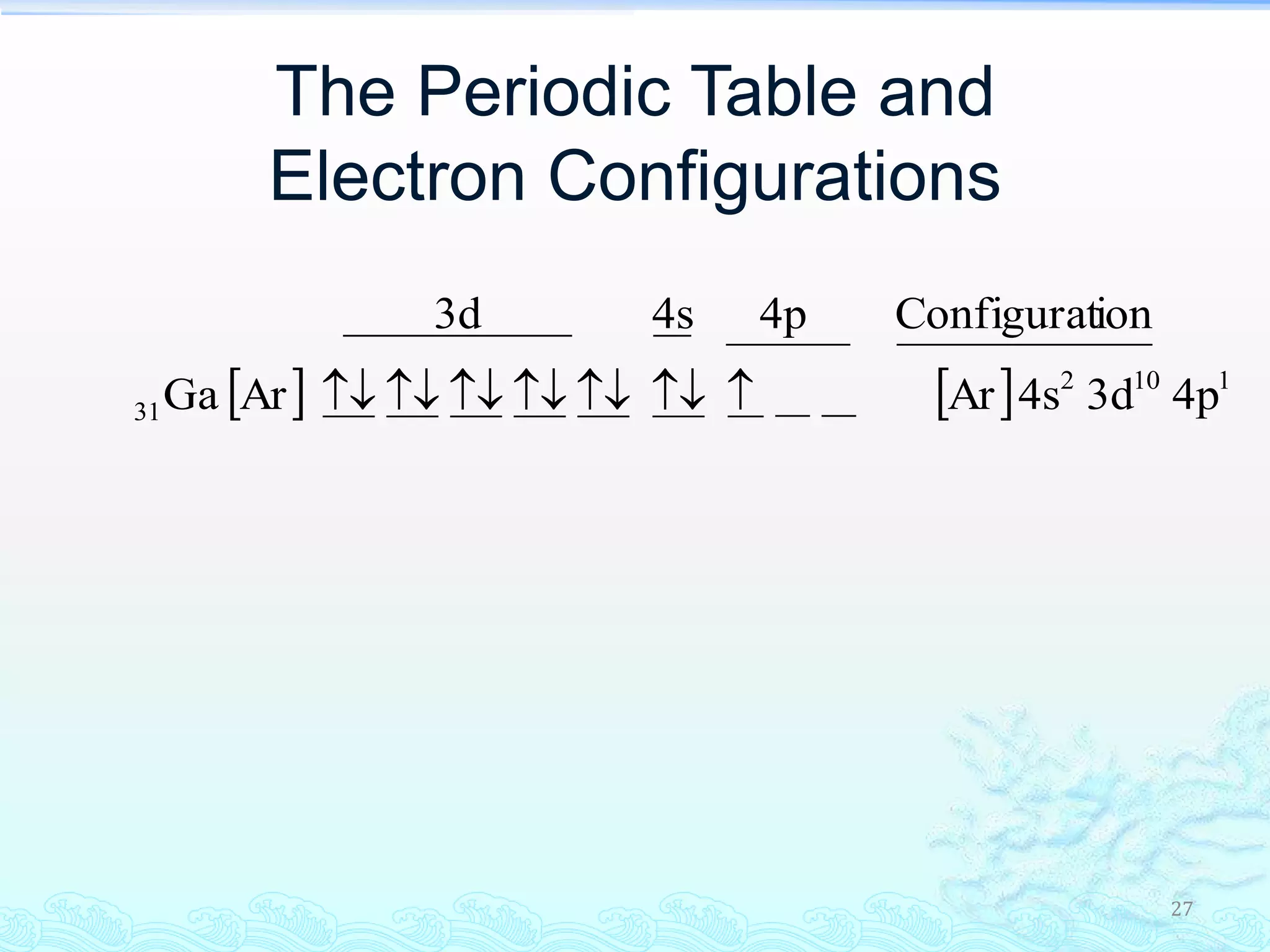

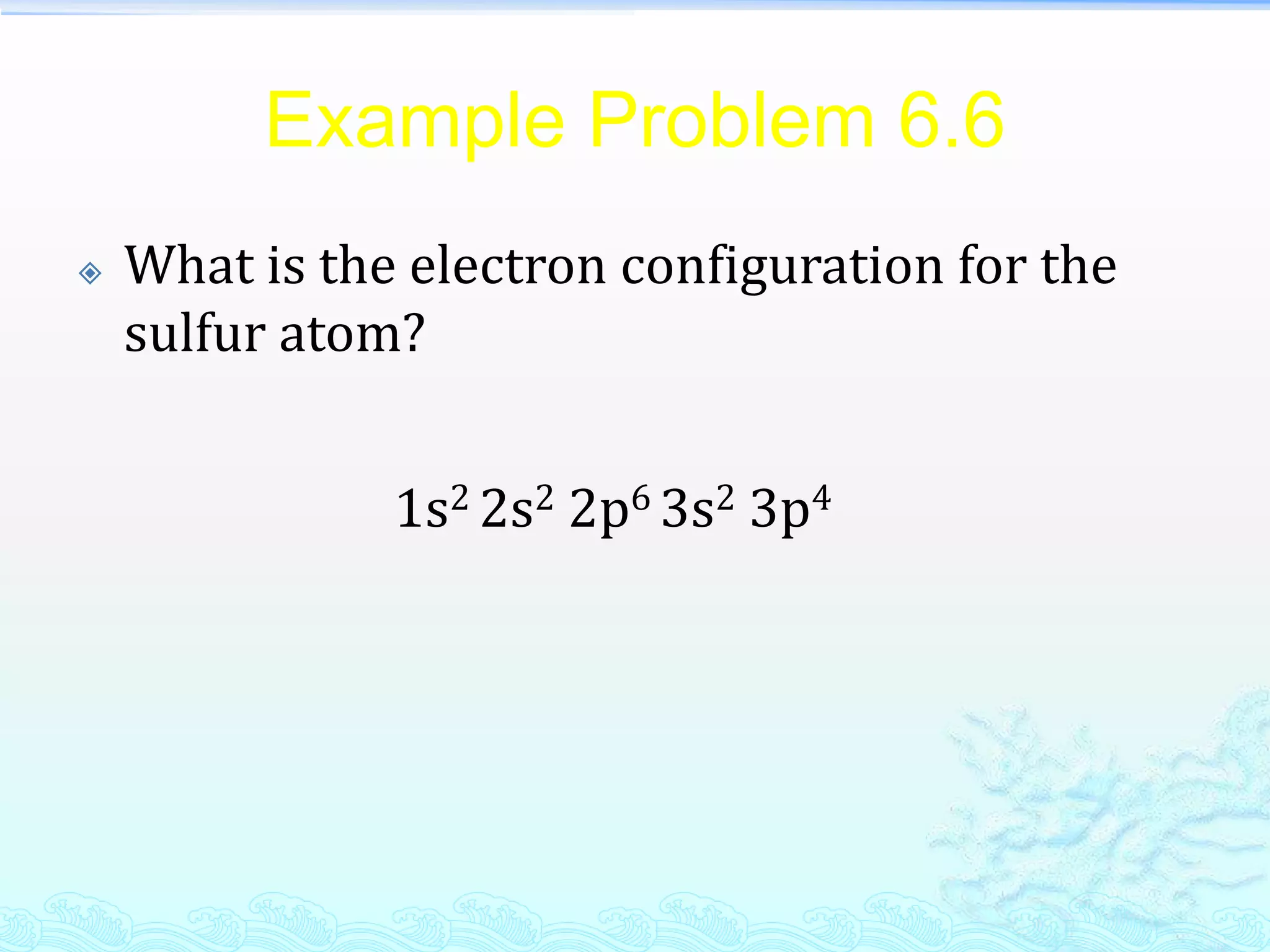

A simplified depiction uses superscripts to indicate

the number of electrons in an orbital set.

1s2 2s2 2p2 is the electronic configuration for carbon.

Noble gas electronic configurations are used as a

shorthand for writing electronic configurations.

Relates electronic structure to chemical bonding.

Electrons in outermost occupied orbitals give rise to

chemical reactivity of an element.

[He] 2s2 2p2 is the shorthand for carbon](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l4electronicstructureofatompart2-130906000855-171214133806/75/L4electronicstructureofatompart2-130906000855-13-2048.jpg)

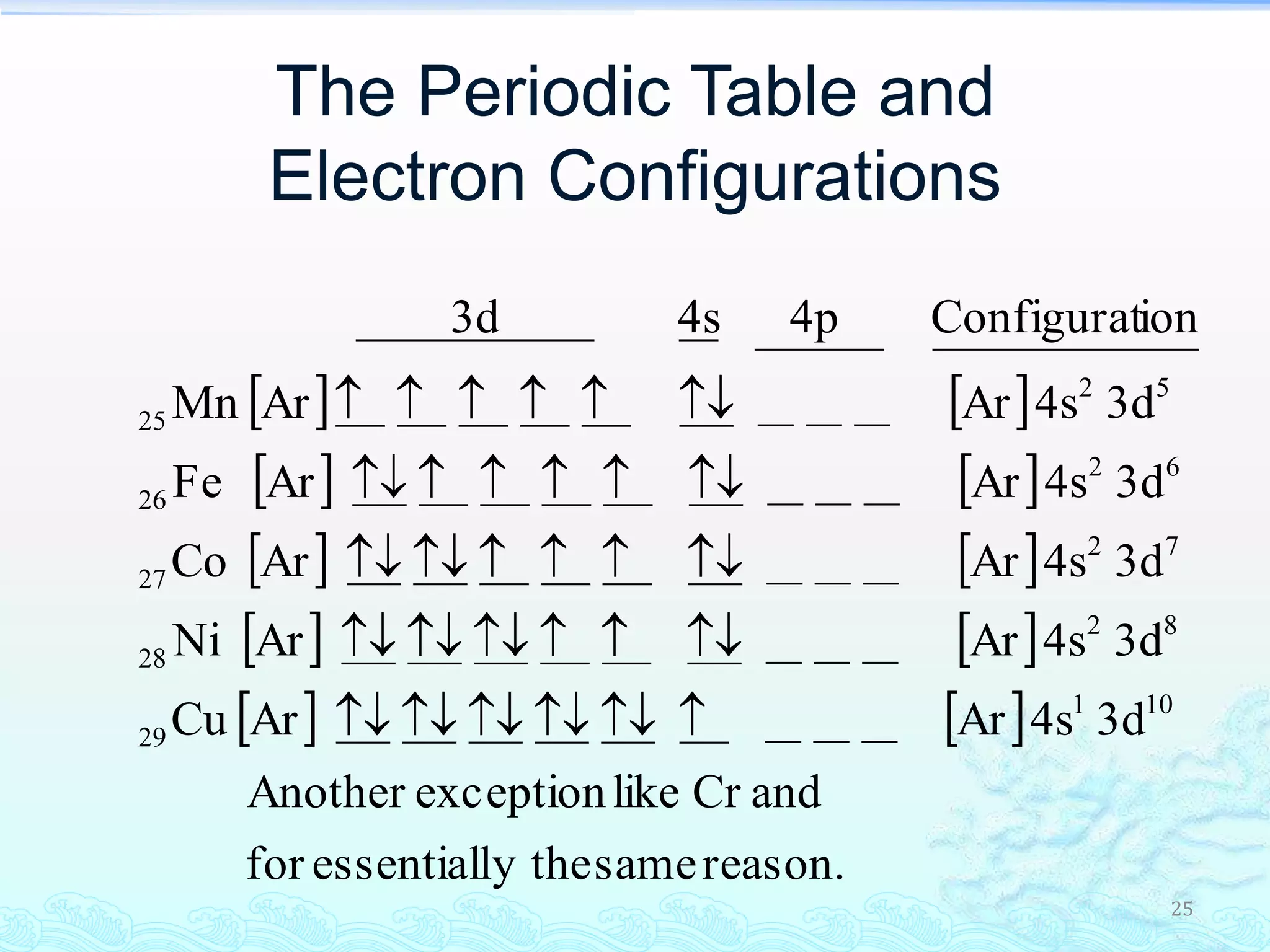

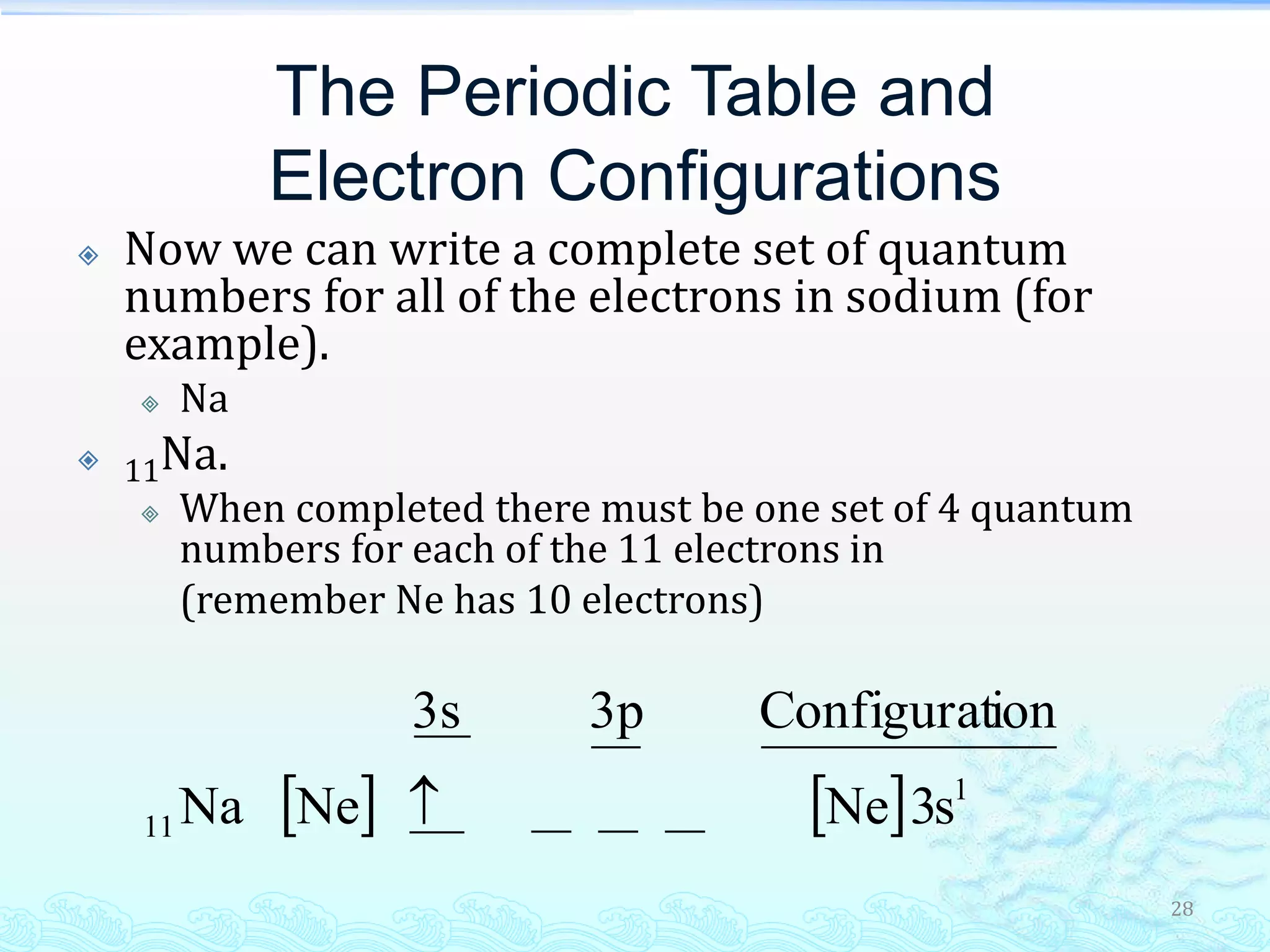

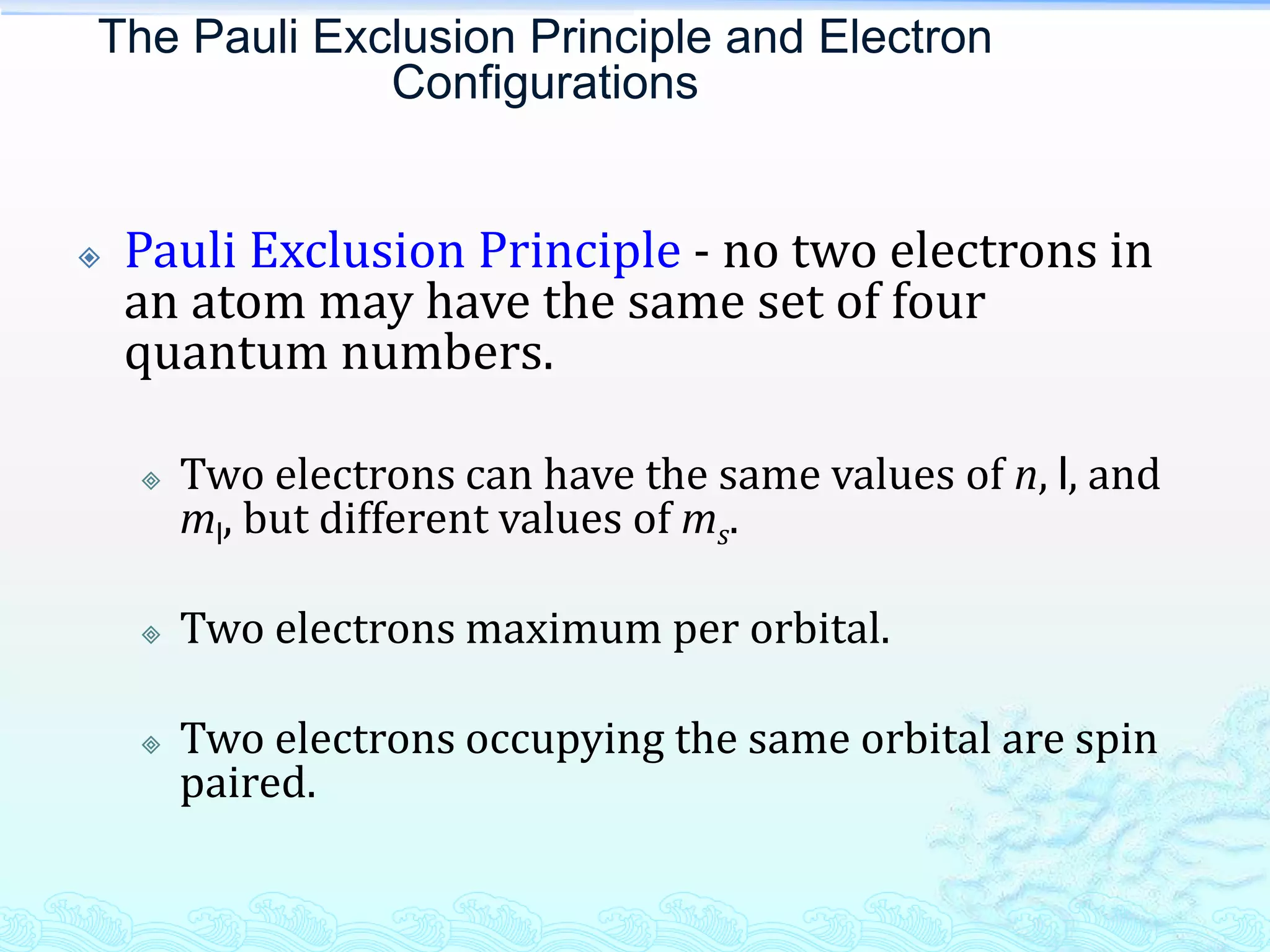

![Example Problem 6.7

Rewrite the electron configuration for sulfur

using the shorthand notation.

[Ne] 1s2 2s2 2p6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l4electronicstructureofatompart2-130906000855-171214133806/75/L4electronicstructureofatompart2-130906000855-15-2048.jpg)

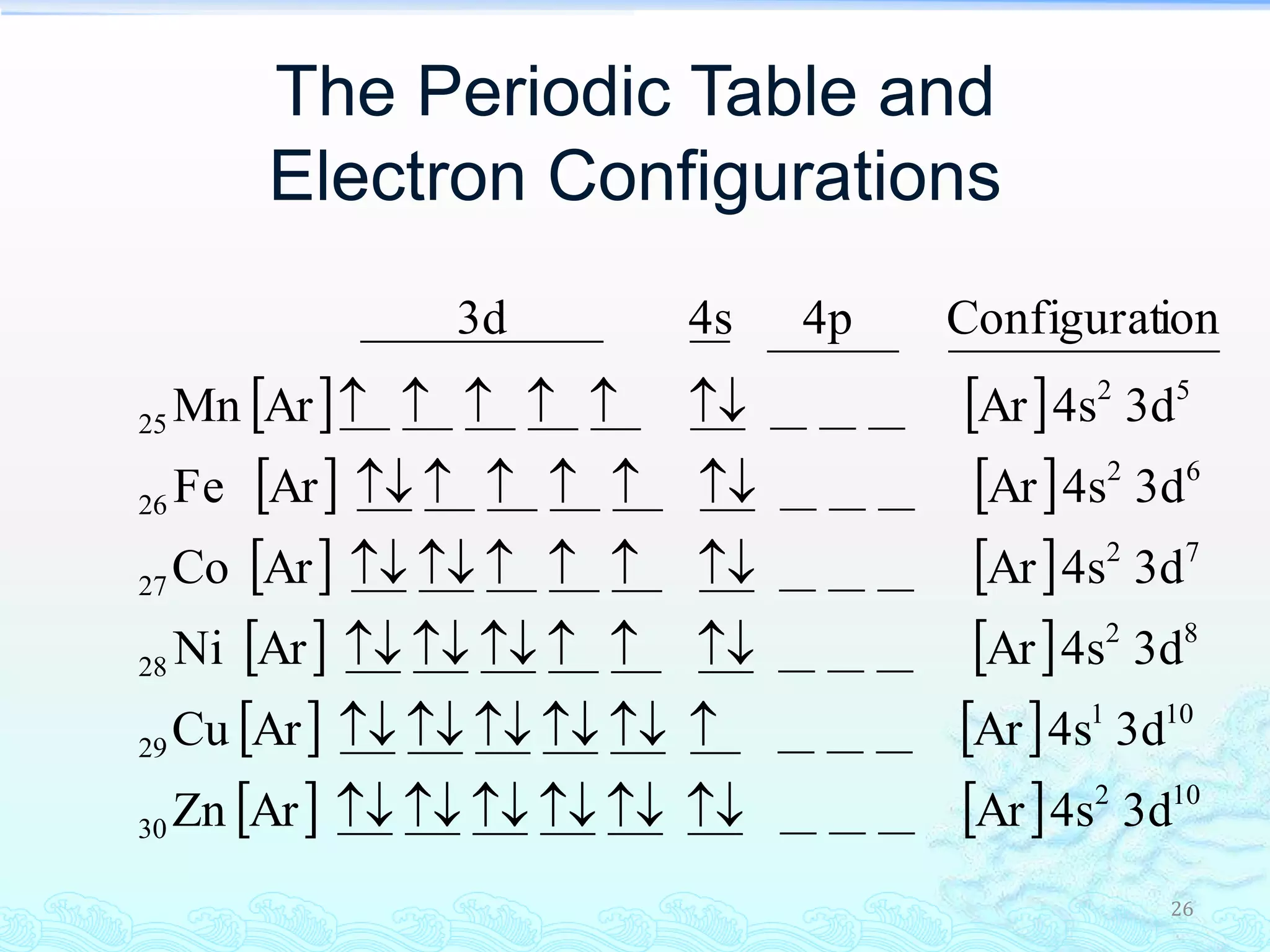

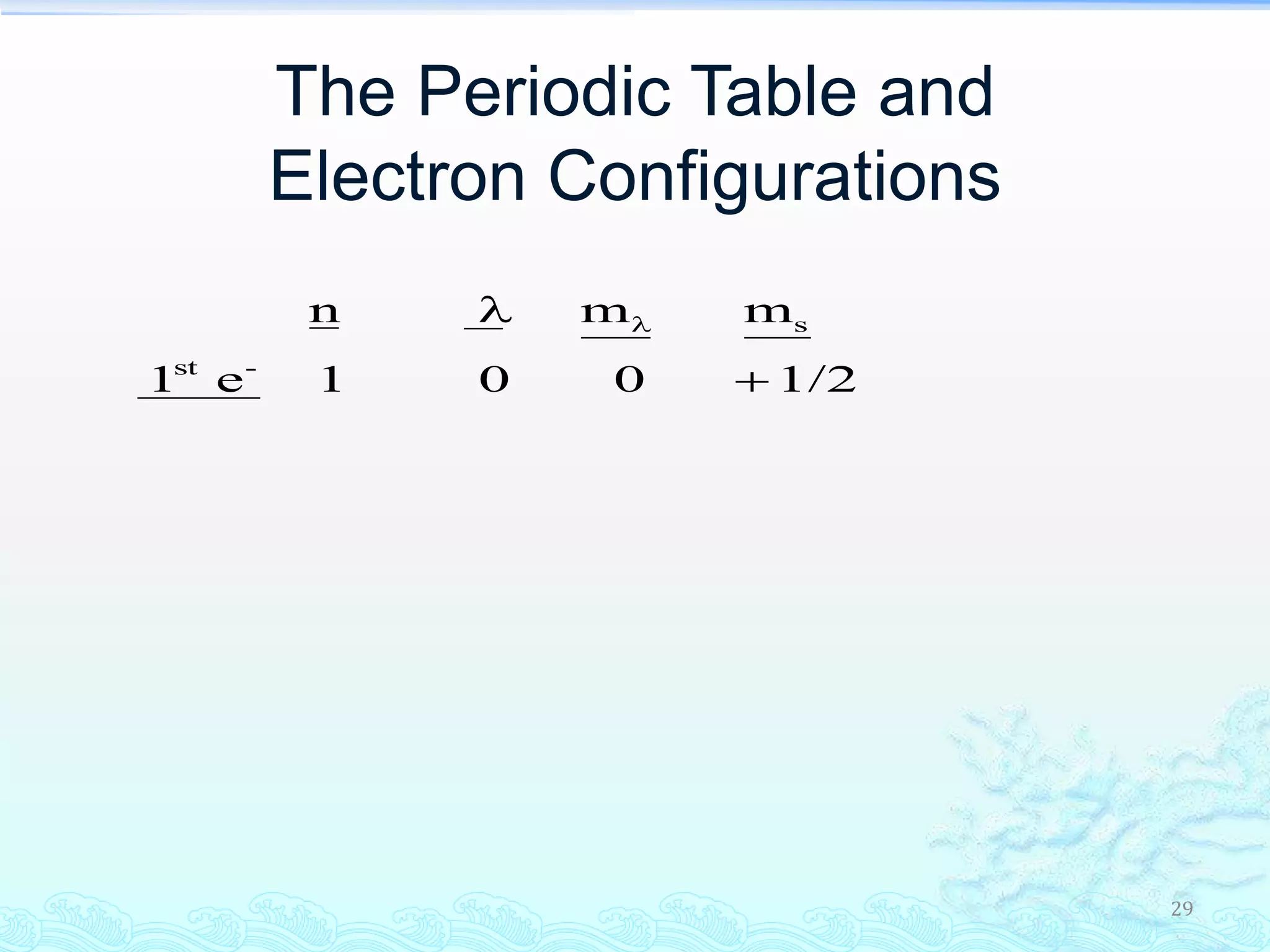

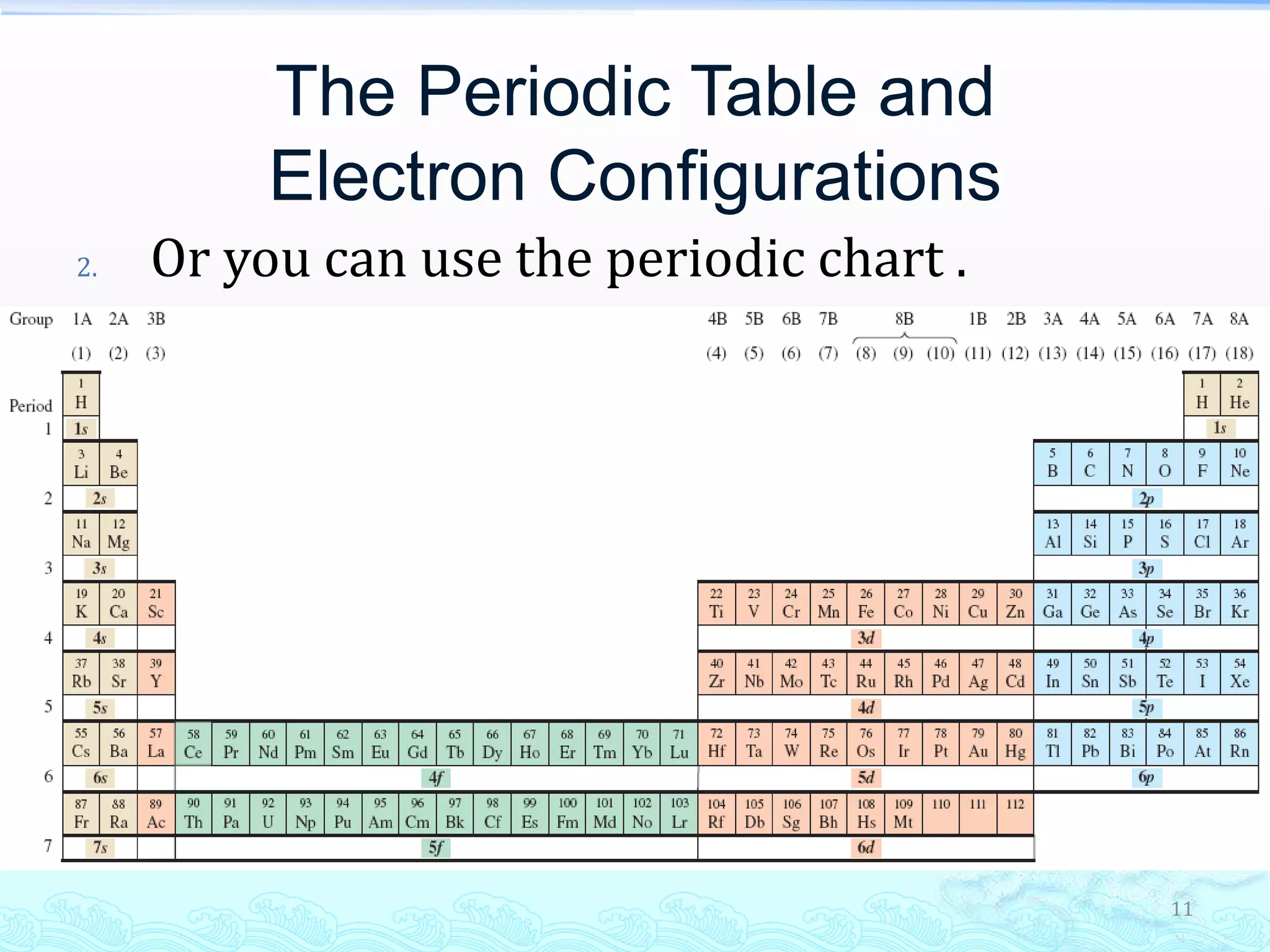

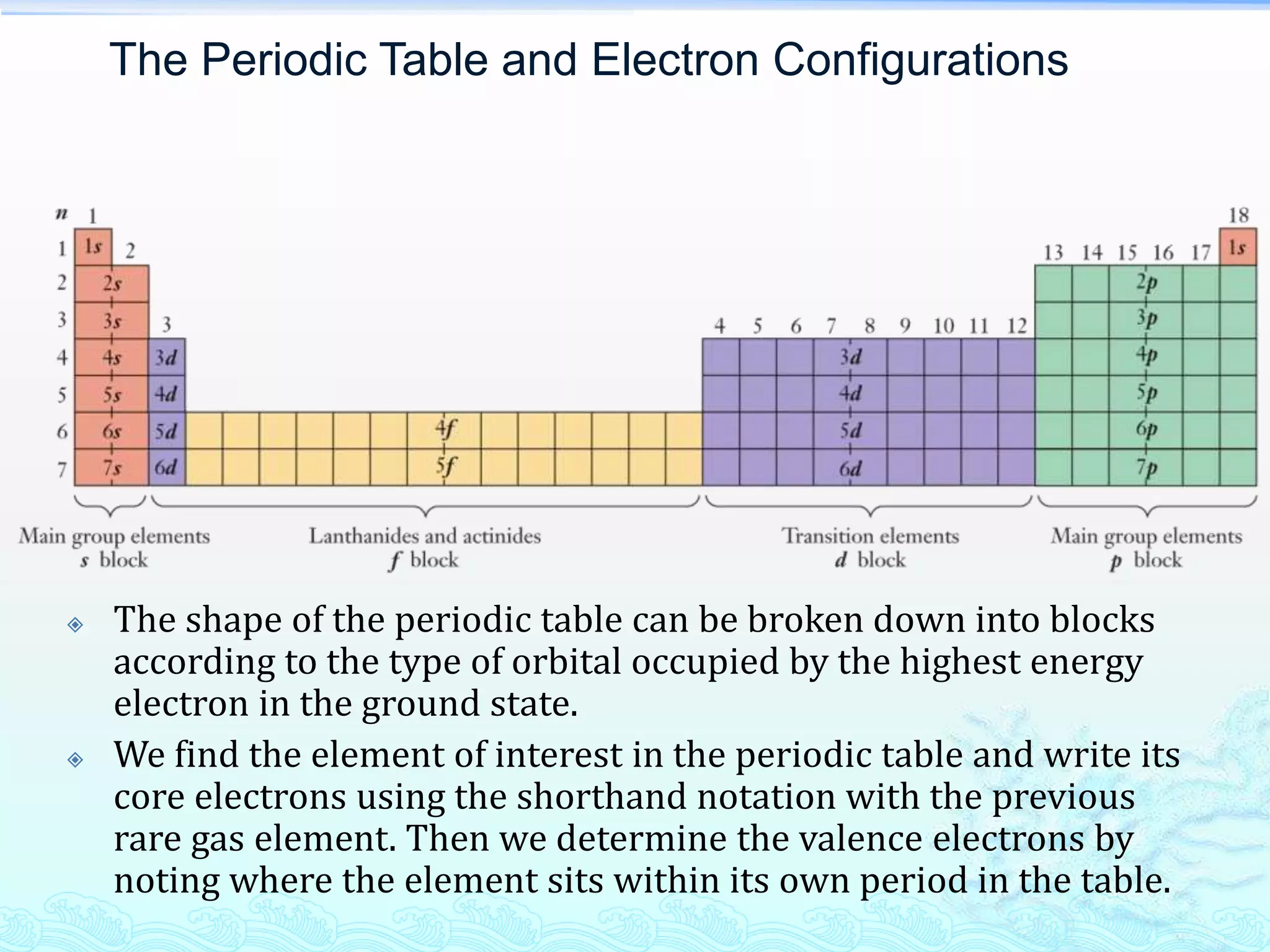

![Example Problem 6.8

Use the periodic table to determine the

electron configuration of tungsten (W),

which is used in the filaments of most

incandescent lights.

[Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l4electronicstructureofatompart2-130906000855-171214133806/75/L4electronicstructureofatompart2-130906000855-18-2048.jpg)