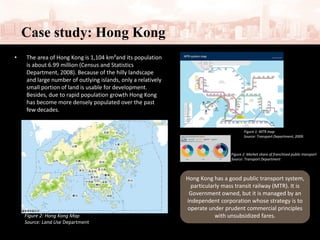

The document discusses public-private partnerships (PPPs) and their potential benefits and drawbacks for delivering infrastructure services. PPPs aim to leverage private sector expertise and financing to strengthen infrastructure quality and quantity while reducing costs and construction timelines. However, the prioritization of low costs over performance and potential conflicts between public and private sector goals may undermine value and public interests. The document also examines Hong Kong's successful PPP for its mass transit railway system as a case study.