This document discusses the role of science and technology in the Industrial Revolution in England. It covers several key points:

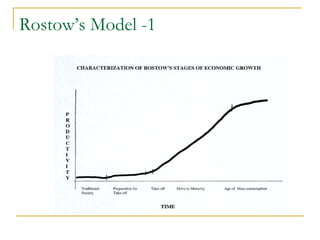

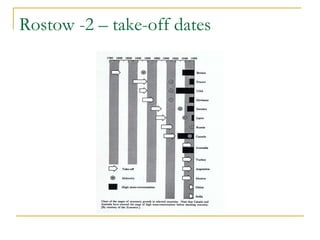

1. It outlines Rostow's model of stages of economic growth and identifies take-off dates for England's Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century.

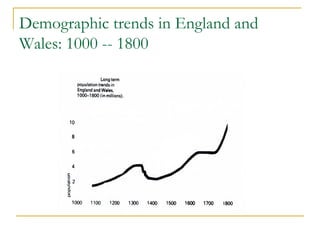

2. It discusses how agricultural innovations like crop rotation led to population growth and a surplus of labor that could be used industrially. Innovations were influenced by scientific practices.

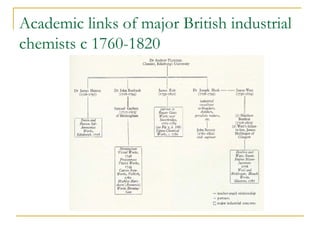

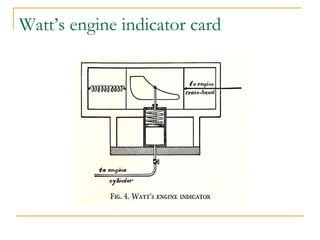

3. Technological innovations in transportation like canals and railroads helped spur industrialization. Many innovators like Brindley, Boulton, and Watt were scientifically trained.

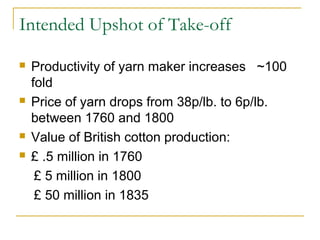

4. Mechanizations of textile production through inventions like the

![Science and Drive to Maturity

Fueled heavily by chemical processes

Bleaching story told in reading

Wedgewood story told in reading

One begins to see scientific knowledge as well as attitudes and

practices playing a greater role

Soda production story: Soda (NaCO3) needed for baking & for mgfr.

of soaps & glass –traditionally produced by burning kelp, but demand

grows too rapidly for supply to keep up

French Academie des Sciences offers 12,000 livre prize for invention

of commercially feasible method. Chemist Joseph LeBlanc wins

(heat salt with sulphuric acid, creates sodium sulphate; heat with

limestone & coal [carbon], sodium carbonate[soda] leached out with

water & collected by evaporating water)

Eban Horsford story in U.S.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/industrialrevolution-120203082818-phpapp01/85/Industrial-revolution-23-320.jpg)