Hydrogen can be produced through various methods such as steam reforming of natural gas, partial oxidation of hydrocarbons, thermochemical water splitting using high temperatures, electrolysis of water, radiolysis of water through nuclear radiation, and biological and enzymatic conversion of biomass. Each method has its advantages and disadvantages related to efficiency, costs, environmental impacts, and scalability. Hydrogen is a very useful energy carrier due to its high energy content per unit mass and non-polluting nature when used.

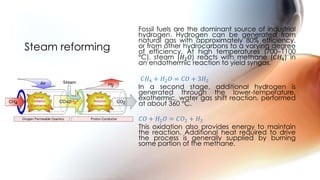

![The partial oxidation reaction occurs when

a sub-stoichiometric fuel-air mixture is

partially combusted in a reformer, creating

a hydrogen-rich syngas. A distinction is

made between thermal partial oxidation

(TPOX) [ ≥ 1200°C] and catalytic partial

oxidation (CPOX) [800°C-900°C]. The

chemical reaction takes the general form:

𝐶 𝑛 𝐻 𝑚 +

𝑛

2

𝑂2 → 𝑛𝐶𝑂 +

𝑚

2

𝐻2

Idealized examples for heating oil and coal,

assuming compositions 𝐶12 𝐻24 and 𝐶12 𝐻12

respectively, are as follows:

𝐶12 𝐻24 + 6𝑂2 → 12𝐶𝑂 + 12𝐻2

𝐶24 𝐻12 + 12𝑂2 → 12𝐶𝑂 + 12𝐻2

Partial oxidation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hydrogengeneration-150909084746-lva1-app6891/85/Hydrogen-generation-4-320.jpg)