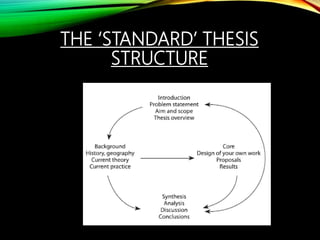

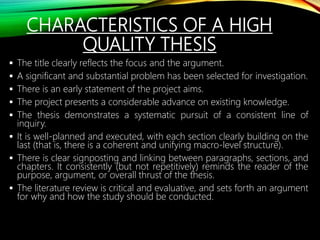

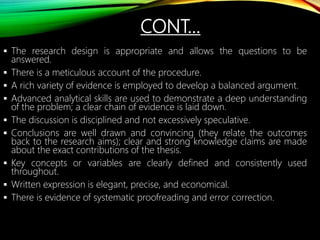

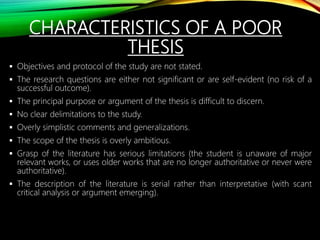

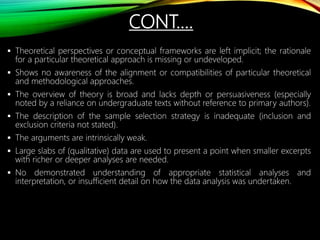

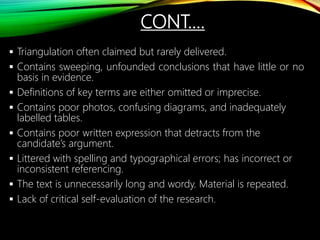

The document provides a comprehensive guide on how to write a successful thesis, outlining essential attributes such as demonstrating authority and originality, and the importance of a clear structure. It covers the thesis components including introduction, background, core, synthesis, findings, discussion, and conclusions, along with practical tips for effective writing and organization. Additionally, it highlights characteristics of both high-quality and poor theses, offering insights into research methodology and presentation of results.