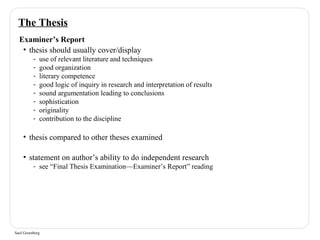

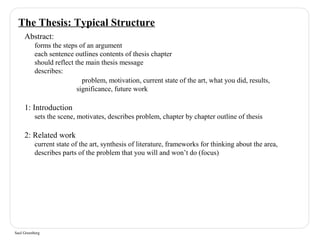

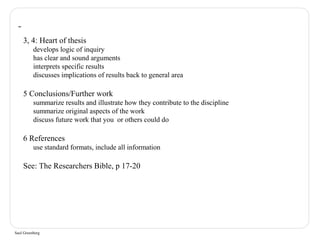

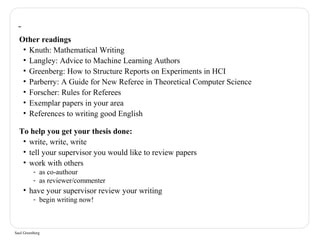

This document provides guidance on writing research papers and theses. It discusses the typical structures and contents of papers and theses, as well as how referees evaluate papers. Papers should communicate important new ideas or information to advance knowledge in a field. They have standard sections like an abstract, introduction, body, and conclusion. Theses allow for more in-depth arguments and are evaluated based on the use of literature, organization, logic, argumentation, and contribution to the discipline. Figures and tables should assist the reader in understanding concepts discussed in the text.