Third-year nursing students at a university were surveyed about their learning styles and satisfaction with high-fidelity simulation (HFS). The majority of students were found to have a diverging learning style, which prefers reflecting on experiences. Students also scored highest on active experimentation, indicating a preference for learning through experiences rather than theoretically. Overall, students were highly satisfied with HFS and felt it incorporated effective teaching strategies and helped with clinical learning. However, further examination is needed to ensure HFS consistently helps prepare students for practice by accommodating different learning styles and characteristics.

![More simulations would be beneficial in applying our

understanding and prioritising patient needs.

dParticipant #27

There should be more simulations that aren’t neces-

sarily marked as an assessment but allows us more

opportunities to practice to different scenarios.

dParticipant # 60

Participants believed increasing the frequency of simu-

lations would better equip them to prioritize patient needs

and assist them to experience a diverse range of clinical

scenarios. Simulation design included comments on the

high ratio of participant to manikin (4:1) and its negative

impact on the simulation experience.

I believe that 4 student participants is too much, and

can hinder other students learning experience in the

simulation.

dParticipant # 2.

The challenges in treating a manikin like a real person

rather than using student volunteers as the patient to

improve the fidelity of the simulation and the negative

impact of the reduced length of debrief on learning were

also hindrances to learning.

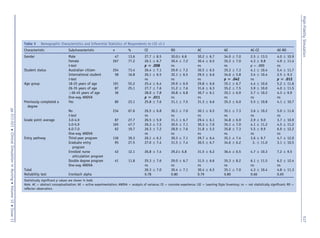

The response rate for the Reflective Thinking and Simu-

lation survey was 346; however, n ¼ 32 (9.3%) participant

questionnaires were excluded from the study due to incom-

plete or incorrect responses, resulting in analysis of 314

participant Kolb LSI v 3.1 surveys. Most participants who

responded to the LSI v 3.1 were female n ¼ 267 (77.2%) and

between the ages of 18 and 25 years (n ¼ 191, 55.2%). Almost

74% of respondents were domestic students (Australian

citizens) (Table 5). Sixty-seven percent of participants had

not previously completed a degree and just under half

(47.7%) of the participants had a GPA ranging from 5.0 to 5.9.

LSI: Learning Characteristics

The mean concrete experience [CE] total score was lower

(26.3) than the other three learning characteristics (reflector

observation [RO] ¼ 30.4; abstract conceptualization

[AC] ¼ 30.4; and active experimentation [AE] ¼ 35.1).

When compared to the Kolb LSI v3.1 total normative group

(Kolb Kolb, 2005), the results of this study are similar,

with small differences in RO (30.4/28.2) and AC (30.4/

32.2). The mean CE score was significantly greater in

male students compared to female students (Table 5). The

mean AE score was greater in Australian citizen/domestic

students compared to international students. The mean

score for CE was significantly greater in the 36- to 45-

year-old age group, compared to the 18- to 25-year-old

age category (p ¼ .027). The analysis of the mean AE score

revealed no significant differences for participants who had

completed a previous degree, GPA between 6.0 and 7.0 and

whose entry pathway was via enrolled nurse articulation.

The overall mean score for the AE-RO scale was 4.8 and

4.3 for the AC-CE scale. Internal consistency was good

(0.80) for the CE total score. Cronbach’s alpha improved to

0.81 if item 11.1 was removed. The RO subscale demon-

strated a good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha

of 0.8. An increase in this value to 0.81 was achieved with

the removal of item 5.2. Both AC and AE displayed good

internal consistency, with Cronbach alphas of 0.79 and 0.80,

respectively. An increase in Cronbach’s alpha for AE

resulted with the removal of item 3 (0.80). These values

are similar to those previously reported by Kolb and Kolb

(2005) in the norm subsample of online LSI users

(n ¼ 5,023). Reliability of AC-CE and AE-RO subscales

were 0.66 and 0.65, respectively. Removal of items 5C

from the AC-CE subscale and item 5B from the AE-RO sub-

scale resulted in an increase in the Cronbach’s alpha values

to 0.68 and 0.67, respectively.

LSI: Learning Styles

The learning styles of the third-year undergraduate nursing

students were diverging (n ¼ 103; 29.8%), followed by

accommodating (n ¼ 87; 25.1%), then assimilating

(n ¼ 67; 19.4%), closely followed by converging

(n ¼ 57; 16.5%). A chi-square test for independence

indicated no significant association between gender and

learning styles and age and learning styles (Table 6).

Discussion

The subscale AE was the highest mean score compared to

CE as the lowest mean score. This suggests that simulation is

a good fit for third-year undergraduate nursing students.

Students with this type of preferred learning characteristic

have learning skills for success in technology careers such as

nursing and medicine (Shinnick Woo, 2013). It identified

that these students have the ability to learn from primarily

Table 6 Chi-Square Analysis of Learning Styles for Gender and Age (n ¼ 314)

Demographics Accommodating Diverging Converging Assimilating

Gender c2

(1) ¼ 0.03, p ¼ .866 c2

(1) ¼ 0.10, p ¼ .757 c2

(1) ¼ 1.55, p ¼ .213 c2

(1) ¼ 1.80, p ¼ .180

Age c2

(2) ¼ 0.32, p ¼ .854 c2

(2) ¼ 4.62, p ¼ .099 c2

(2) ¼ 1.70, p ¼ .427 c2

(2) ¼ 0.40, p ¼ .818

High-Fidelity Simulation 518

pp 511-521 Clinical Simulation in Nursing Volume 12 Issue 11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8a964021-45a9-455c-8da1-093e61ed0e78-160921064642/85/High-fidelity-simulation_Descriptive-analysis-of-student-learning-styles_CSN-8-320.jpg)

![http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.04.004. Retrieved from http://

www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0260691712001098.

Smith E. (2011). Teaching critical reflection. Teaching in higher educa-

tion [serial online]. Ipswich, MA: Academic Search Elite;16(2):

211-223.

Swanson, E. A., Nicholson, A. C., Boese, T. A., Cram, E., Stineman, A. M.,

Tew, K. (2011). Comparison of selected teaching strategies incorporating

simulation and student outcomes. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 7(3),

e81-e90, ISSN 1876-1399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2009.12.011.

Teixeira, C. R. d. S., Kusumota, L., Pereira, M. C. A., Braga, F. T. M. M.,

Gaioso, V. P., Zamarioli, C. M., de Carvalho, E. C. (2014). Anxiety

and performance of nursing students in regard to assessment via clinical

simulations in the classroom versus filmed assessments. Investigacion

y Educacion En Enfermerıa, 32(2), 270-279, Retrieved from http://

search.proquest.com/docview/1552719984?accountid¼13380.

Tutticci, N., Lewis, P. A., Coyer, F. (2016). Measuring third year under-

graduate nursing students’ reflective thinking skills and critical reflec-

tion self-efficacy following high fidelity simulation: A pilot study.

Nurse Education in Practice, 18(5), 52-59.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Interaction between learning and development.

In: Vygotsky, L. (Ed.), Mind and Society. Cambridge, MA: Har-

vard University Press. (pp. 79-91).

Wotton, K., Davis, J., Button, D., Kelton, M. (2010). Third-year under-

graduate nursing students’ perceptions of high-fidelity simulation. Jour-

nal of Nursing Education, 49(11), 632-639. http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/

01484834-20100831-01.

High-Fidelity Simulation 521

pp 511-521 Clinical Simulation in Nursing Volume 12 Issue 11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8a964021-45a9-455c-8da1-093e61ed0e78-160921064642/85/High-fidelity-simulation_Descriptive-analysis-of-student-learning-styles_CSN-11-320.jpg)