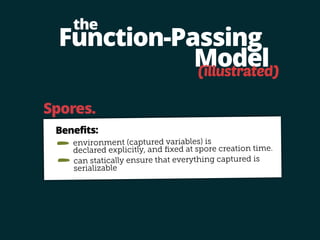

This document discusses a function-passing programming model for distributed systems. The key concepts are:

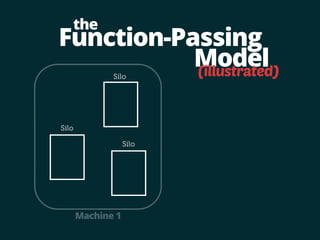

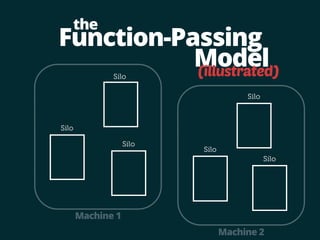

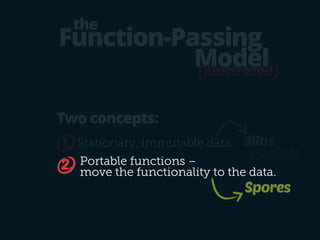

1. Immutable, stationary data stored in "silos".

2. Portable "spore" functions that are serialized and sent to remote silos to perform work on the data.

Silos contain the data and run functions on it. Silo references allow applying functions asynchronously across machines by serializing the functions and data references. The model aims to simplify distributed programming by keeping data stationary and moving functions to the data.

![Function-Passing

Model

the

(illustrated)

Silo[T]

T

Silos.

WHAT ARE THEY?

SiloRef[T]

def

apply

def

send](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-26-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Model

the

(illustrated)

Silo[T]

T

Silos.

WHAT ARE THEY?

SiloRef[T]

def

apply

def

send

The handle to a Silo.

(The workhorse.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-27-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Model

the

(illustrated)

Silo[T]

T

Silos.

WHAT ARE THEY?

SiloRef[T]

def

apply

def

send

The handle to a Silo.

def

apply(s1:

Spore,

s2:

Spore):

SiloRef[T]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-28-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Model

the

(illustrated)

Silo[T]

T

Silos.

WHAT ARE THEY?

SiloRef[T]

def

apply

def

send

The handle to a Silo.

def

apply(s1:

Spore,

s2:

Spore):

SiloRef[T]

Ta k e s t w o s p o r e s :

LAZY!

framework logic (combinator), e.g. map

user/application-provided argument function

Defers application of fn to silo, returns SiloRef

with info for later materialization of silo.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-29-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Model

the

(illustrated)

Silo[T]

T

Silos.

WHAT ARE THEY?

SiloRef[T]

def

apply

def

send

The handle to a Silo.

def

apply(s1:

Spore,

s2:

Spore):

SiloRef[T]

def

send():

Future[T]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-30-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Model

the

(illustrated)

Silo[T]

T

Silos.

WHAT ARE THEY?

SiloRef[T]

def

apply

def

send

The handle to a Silo.

def

apply(s1:

Spore,

s2:

Spore):

SiloRef[T]

Sends info for function application

and silo materialization to remote node

EAGER!

def

send():

Future[T]

Asynchronous/nonblocking data transfer to

local machine (via Future)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-31-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Model

the

Silo[T]

(illustrated)

SiloRef[T]

T

Machine 1 Machine 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-32-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Model

the

Silo[T]

(illustrated)

SiloRef[T]

λ

T T⇒S

Machine 1 Machine 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-33-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Model

the

Silo[T]

(illustrated)

SiloRef[T]

λ

T

)

SiloRef[S]

Machine 1 Machine 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-34-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Model

the

Silo[T]

(illustrated)

SiloRef[T]

λ

T

)

SiloRef[S]

Silo[S] )

S

Machine 1 Machine 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-35-320.jpg)

![SURJUDPPLQJ ODQJXDJHV RXWVLGH WKH 6PDOOWDON WUDGLWLRQ DGRSW

LQJ IXQFWLRQDO IHDWXUHV VXFK DV ODPEGDV DQG WKHUHE IXQFWLRQ FORVXUHV +RZHYHU

GHVSLWH WKLV HVWDEOLVKHG YLHZSRLQW RI )3 DV DQ HQDEOHU UHOLDEO GLVWULEXWLQJ IXQF

WLRQ FORVXUHV RYHU D QHWZRUN RU XVLQJ WKHP LQ FRQFXUUHQW HQYLURQPHQWV QRQHWKH

OHVV UHPDLQV D FKDOOHQJH DFURVV )3 DQG 22 ODQJXDJHV 7KLV SDSHU WDNHV D VWHS WR

ZDUGV PRUH SULQFLSOHG GLVWULEXWHG DQG FRQFXUUHQW SURJUDPPLQJ E LQWURGXFLQJ D

QHZ FORVXUHOLNH DEVWUDFWLRQ DQG WSH VVWHP FDOOHG VSRUHV WKDW FDQ JXDUDQWHH FOR

VXUHV WR EH VHULDOL]DEOH WKUHDGVDIH RU HYHQ KDYH FXVWRP XVHUGHILQHG SURSHUWLHV

UXFLDOO RXU VVWHP LV EDVHG RQ WKH SULQFLSOH RI HQFRGLQJ WSH LQIRUPDWLRQ FRU

UHVSRQGLQJ WR FDSWXUHG YDULDEOHV LQ WKH WSH RI D VSRUH :H SURYH RXU WSH VVWHP

VRXQG LPSOHPHQW RXU DSSURDFK IRU 6FDOD HYDOXDWH LWV SUDFWLFDOLW WKURXJK D VPDOO

HPSLULFDO VWXG DQG VKRZ WKH SRZHU RI WKHVH JXDUDQWHHV WKURXJK D FDVH DQDOVLV

RI UHDOZRUOG GLVWULEXWHG DQG FRQFXUUHQW IUDPHZRUNV WKDW WKLV VDIH IRXQGDWLRQ IRU

FORVXUHV IDFLOLWDWHV

.HZRUGV FORVXUHV IXQFWLRQV GLVWULEXWHG SURJUDPPLQJ FRQFXUUHQW SURJUDP

PLQJ WSH VVWHPV

ECOOP’ A SIP:

http://docs.scala-lang.org/sips/pending/spores.html](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-46-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Model

the

(illustrated)

EXAMPLE:

Distributed List with operations map and reduce.

(This is what would be happening under the hood)

SiloRef[List[Int]]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-48-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Model

the

(illustrated)

EXAMPLE:

Distributed List with operations map and reduce.

(This is what would be happening under the hood) (Spores)

SiloRef[List[Int]]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-49-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Model

the

(illustrated)

EXAMPLE:

Distributed List with operations map and reduce.

(This is what would be happening under the hood)

SiloRef[List[Int]]

.apply](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-50-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Model

the

(illustrated)

EXAMPLE:

Distributed List with operations map and reduce.

(This is what would be happening under the hood)

SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[List[Int]]

.apply](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-51-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

EXAMPLE:

Distributed List with operations map and reduce.

(This is what would be happening under the hood)

.apply

Model

the

(illustrated)

SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[List[Int]]

.apply](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-52-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

EXAMPLE:

Distributed List with operations map and reduce.

(This is what would be happening under the hood)

map f

.apply

Model

the

(illustrated)

SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[List[Int]]

.apply](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-53-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Distributed List with operations map and reduce.

SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[Int]

map f

.apply

Model

SiloRef[List[Int]]

map (_*2)

the

(illustrated)

reduce (_+_)

EXAMPLE:

(This is what would be happening under the hood)

.apply .apply](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-54-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Distributed List with operations map and reduce.

SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[Int]

map f

.apply

Model

SiloRef[List[Int]]

map (_*2)

the

(illustrated)

reduce (_+_)

EXAMPLE:

(This is what would be happening under the hood)

.apply .apply .send()](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-55-320.jpg)

![Function-Passing

Model

the

(illustrated)

EXAMPLE:

Distributed List with operations map and reduce.

(This is what would be happening under the hood)

SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[Int]

map f

.apply

SiloRef[List[Int]]

.apply .send()

map (_*2)

reduce (_+_)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-56-320.jpg)

![SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[Int]

map f

.apply

SiloRef[List[Int]]

.apply .send()

map (_*2)

reduce (_+_)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-57-320.jpg)

![SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[Int]

map f

.apply

SiloRef[List[Int]]

.apply .send()

map (_*2)

reduce (_+_)

Machine 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-58-320.jpg)

![SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[Int]

map f

.apply

SiloRef[List[Int]]

.apply .send()

map (_*2)

reduce (_+_)

Machine 1

List[Int]

Silo[List[Int]]

Machine 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-59-320.jpg)

![SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[Int]

map f

.apply

SiloRef[List[Int]]

.apply .send()

map (_*2)

reduce (_+_)

Machine 1

List[Int]

Silo[List[Int]]

Machine 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-60-320.jpg)

![SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[Int]

map f

.apply

SiloRef[List[Int]]

.apply .send()

map (_*2)

reduce (_+_)

Machine 1

List[Int]

Silo[List[Int]]

Machine 2

λ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-61-320.jpg)

![SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[Int]

map f

.apply

SiloRef[List[Int]]

.apply .send()

map (_*2)

reduce (_+_)

Machine 1

List[Int]

Silo[List[Int]]

Machine 2

Int

Silo[Int]

List[Int]

Silo[List[Int]]

List[Int]

Silo[List[Int]]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-62-320.jpg)

![SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[List[Int]] SiloRef[Int]

map f

.apply

SiloRef[List[Int]]

.apply .send()

map (_*2)

reduce (_+_)

Machine 1

List[Int]

Silo[List[Int]]

Machine 2

Int

Silo[Int]

List[Int]

Silo[List[Int]]

List[Int]

Silo[List[Int]]

Int](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/strange-loop-function-passing-141204085956-conversion-gate02/85/Heather-Miller-63-320.jpg)