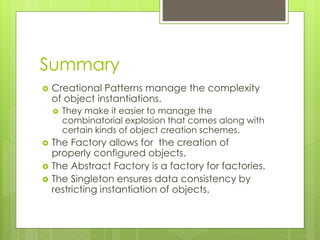

The document introduces creational design patterns, which manage object creation and provide a cohesive interface for complex situations. It discusses three main patterns: the factory, abstract factory, and singleton, detailing their uses and implementations. These patterns help alleviate issues like combinatorial explosion and ensure data consistency in object-oriented programming.