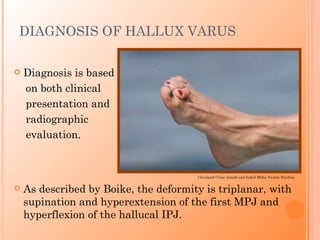

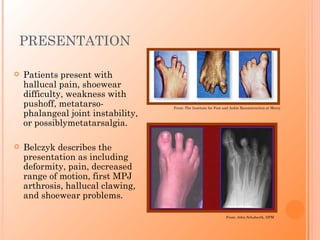

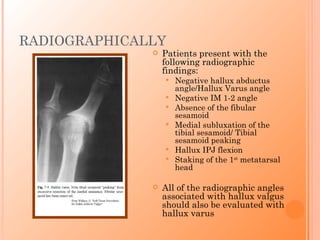

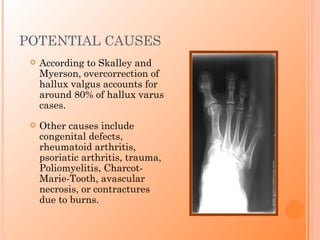

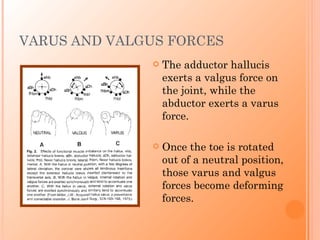

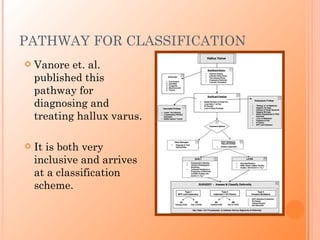

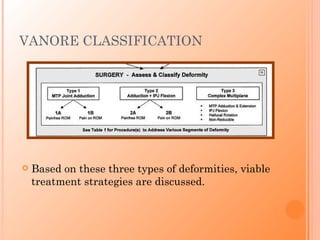

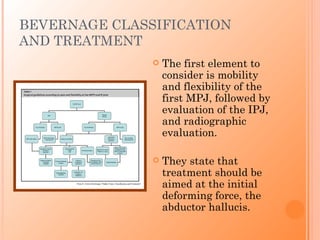

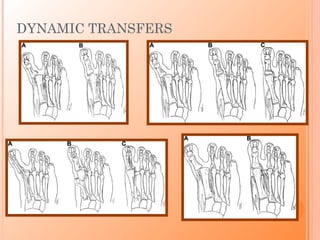

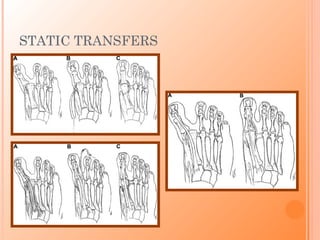

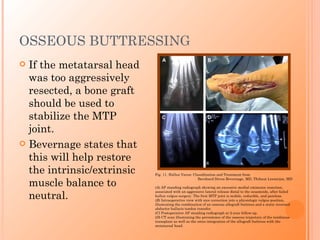

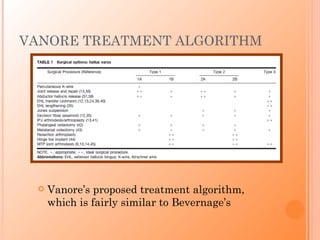

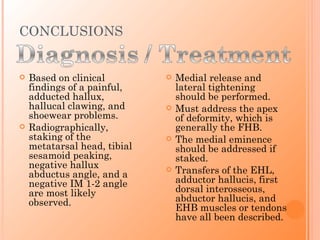

Hallux varus is a deformity of the great toe characterized by three key radiographic findings: a negative hallux abductus angle, negative IM 1-2 angle, and tibial sesamoid peaking. Patients typically present with pain, difficulty with shoes, and decreased push off ability. Treatment begins with orthotics and splinting but often requires surgery involving medial soft tissue release and lateral tightening, with tendon transfers used to correct deformity and maintain correction. Classification systems aim to guide surgical decision making by considering joint flexibility and deforming forces at work.