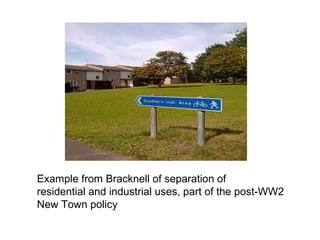

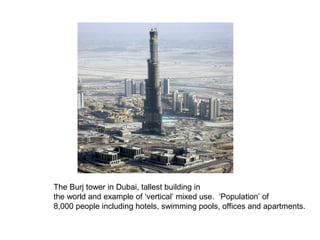

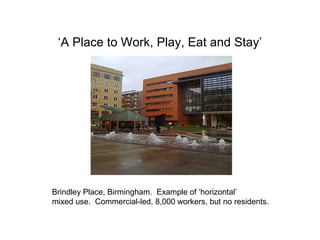

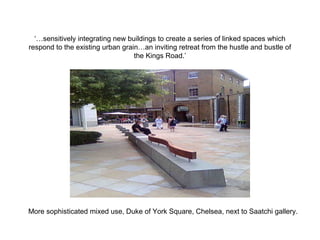

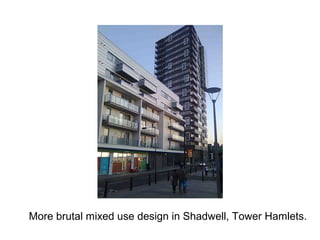

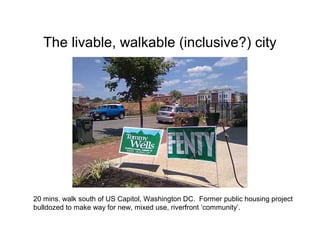

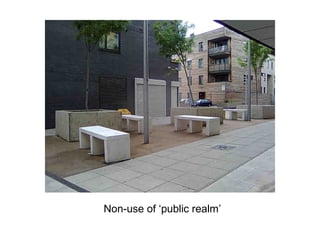

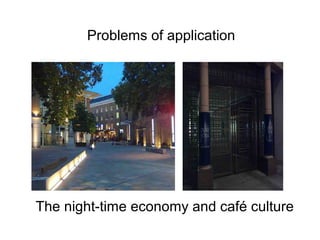

This document discusses the theory and practice of mixed-use property development in urban policy. It begins by exploring definitions of mixed-use and how separating land uses became common in the 20th century. Examples are given of vertical mixed-use like Dubai's Burj Tower and horizontal mixed-use developments. The document then examines the challenges planners face in implementing mixed-use and achieving goals like social integration. A case study of a London neighborhood in transition shows mixed-use there did not necessarily promote social mixing. The document concludes that mixed-use policy has contradictory outcomes and has been more rhetoric than rigorous analysis, raising questions about place, space and rights to the city.