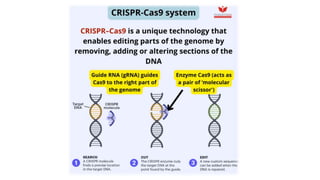

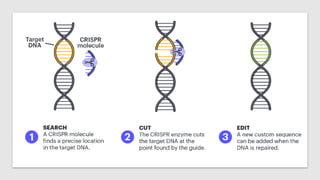

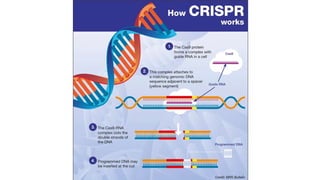

The CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology, derived from bacterial immune systems, allows for precise modifications in DNA by utilizing a guide RNA and the Cas9 protein to cut DNA at specific locations. This method enables two main DNA repair processes—non-homologous end joining and homology-directed repair—which can either disrupt genes or introduce precise modifications. As this technology holds promise for treating genetic disorders, enhancing agriculture, and advancing biotechnology, it also raises ethical considerations and challenges regarding off-target effects and public perception.