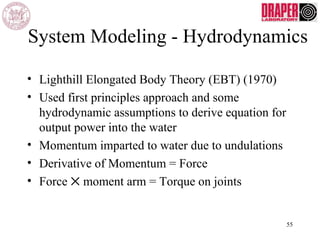

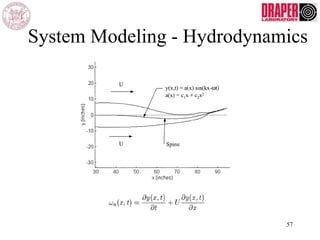

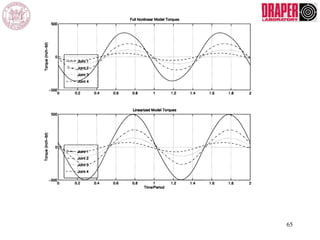

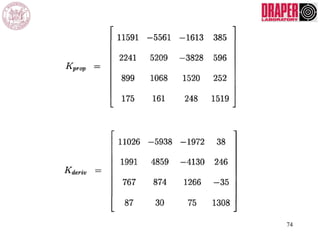

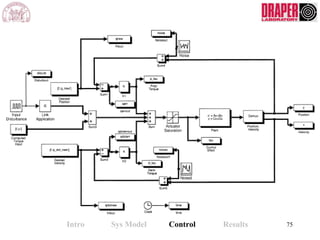

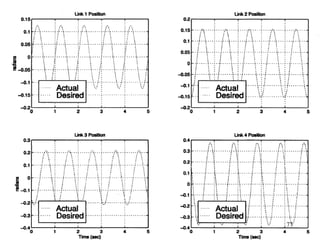

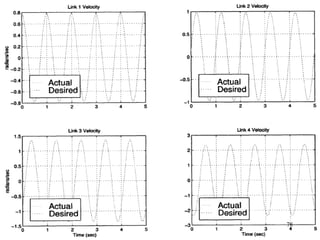

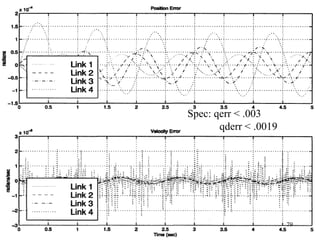

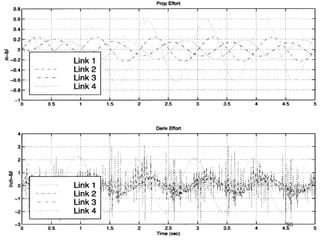

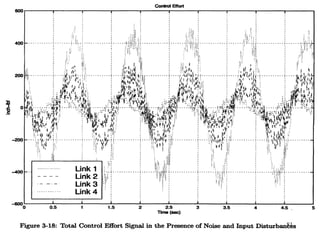

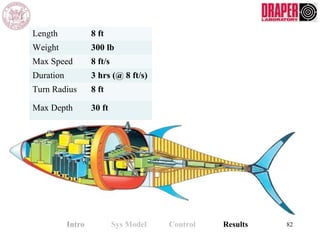

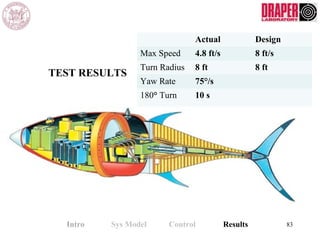

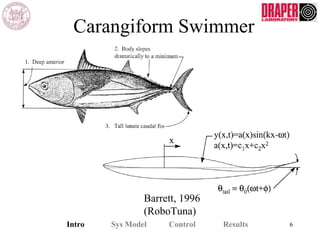

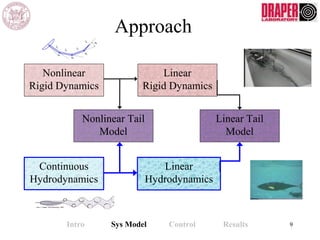

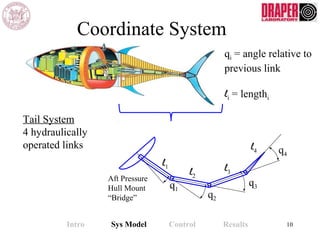

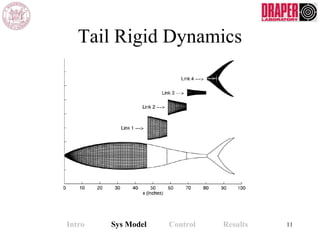

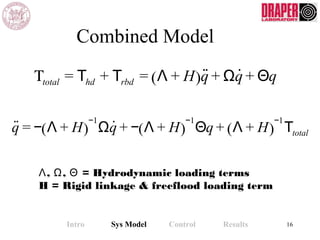

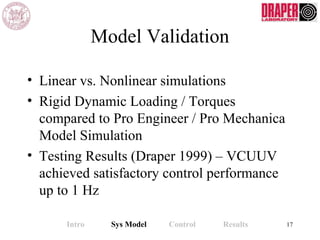

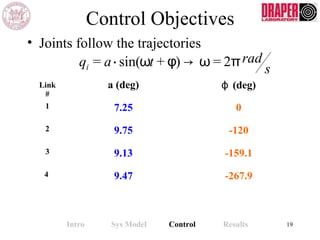

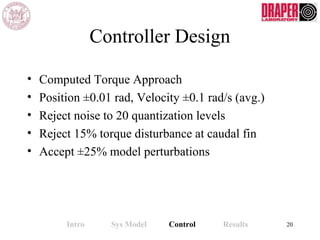

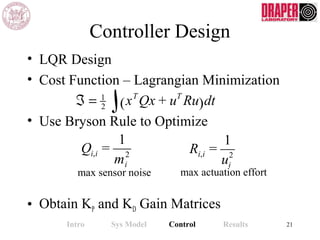

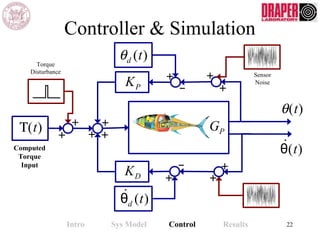

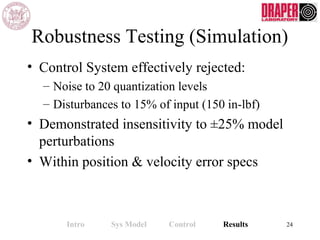

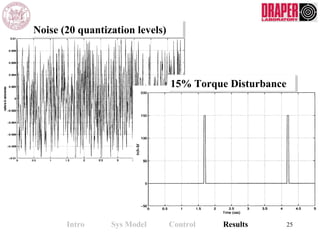

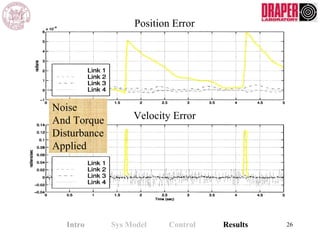

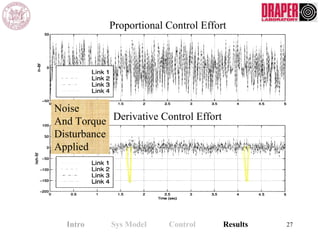

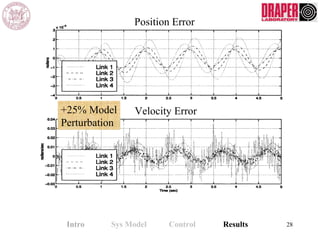

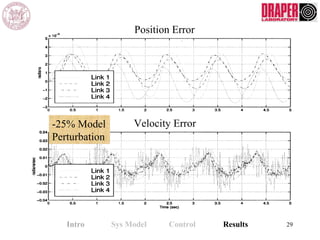

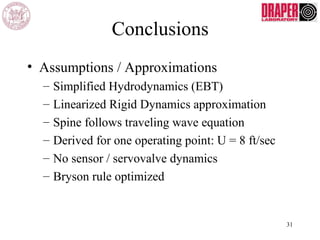

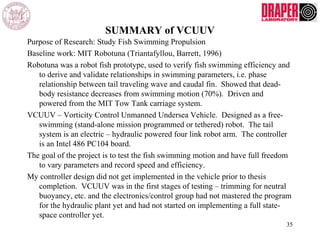

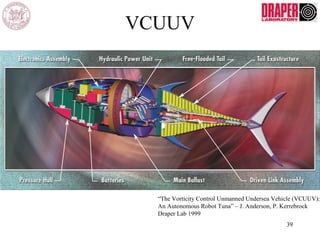

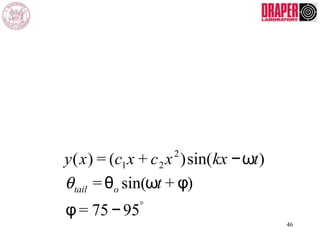

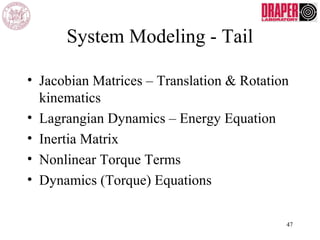

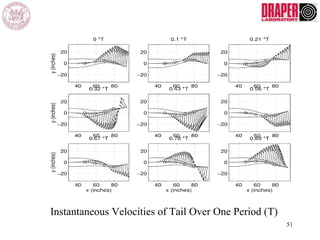

The document describes modeling and control of a Vorticity Control Unmanned Undersea Vehicle (VCUUV) being developed at MIT. It presents the nonlinear rigid body and hydrodynamic models of the vehicle's tail system, which consists of 4 hydraulically operated links that emulate fish swimming. A state-space controller is designed using computed torque and LQR approaches to control the tail's motion and reject disturbances. Simulation results show the controller effectively maintained position and velocity accuracy despite noise, disturbances, and model perturbations.

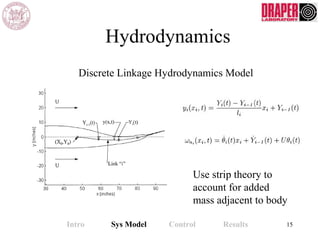

![Hydrodynamics

• Two Major Assumptions of EBT

1. Body Slope fore-aft is negligible [violated]

• Body slope is not extreme and EBT will slightly

overestimate added mass – acceptable engineering

approximation

1. Rigid Cylinder approx for added mass if the

undulation wavelength is at least 5 times the

section depth [good]

Intro Sys Model Control Results 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vcuuv-160521145225/85/Fish-Propulsion-12-320.jpg)

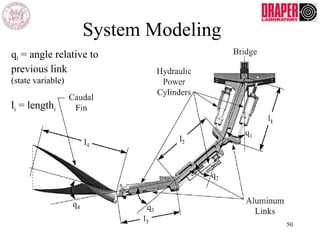

![System Modeling

• Angular (Rotation) Jacobian

J1

A

= q1 0 0 0[ ]

J2

A

= q1 q2 0 0[ ]

J3

A

= q1 q2 q3 0[ ]

J4

A

= q1 q2 q3 q4[ ]

53](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vcuuv-160521145225/85/Fish-Propulsion-48-320.jpg)