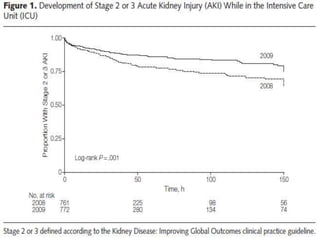

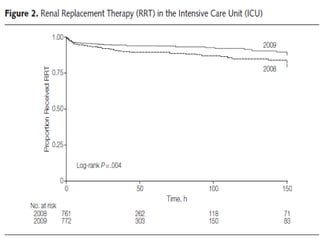

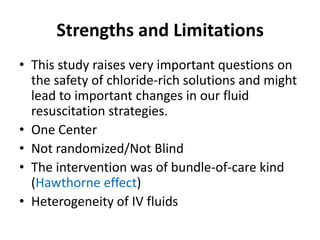

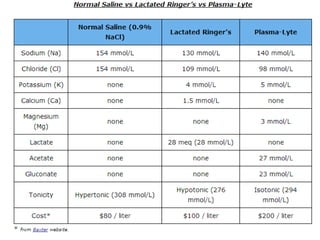

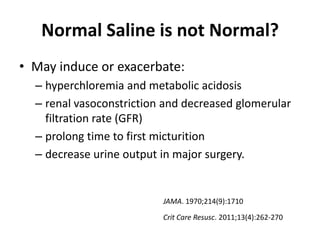

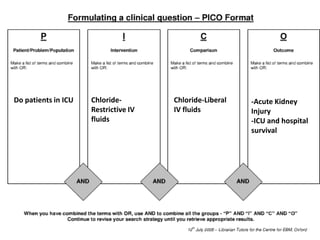

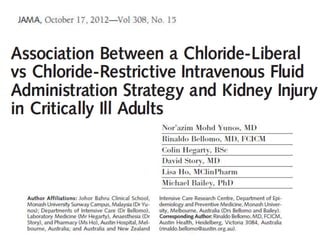

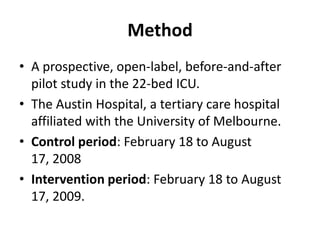

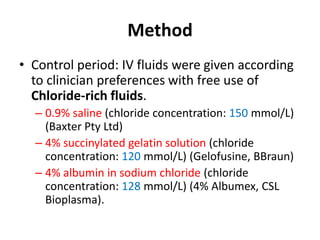

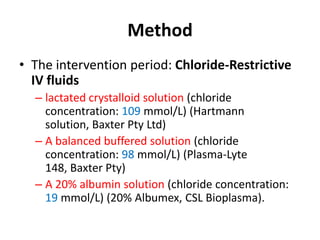

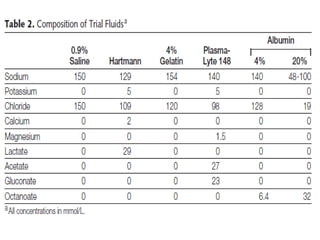

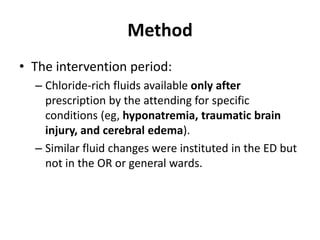

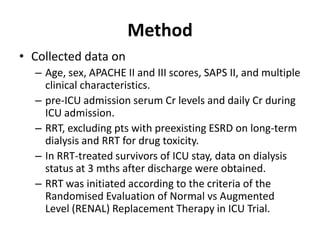

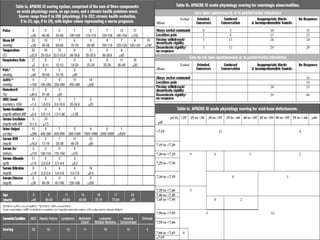

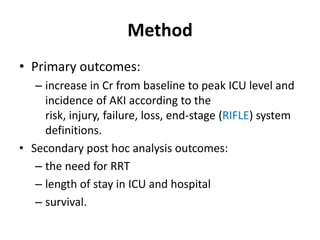

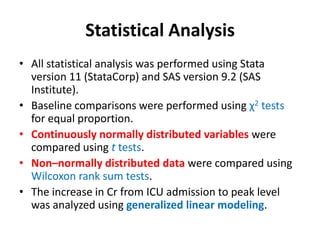

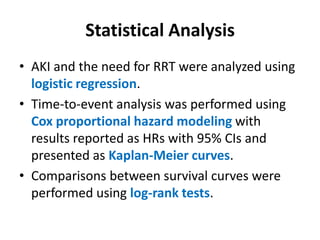

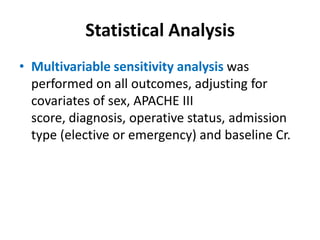

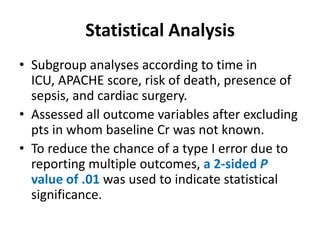

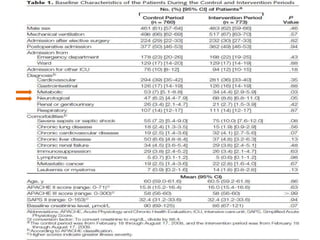

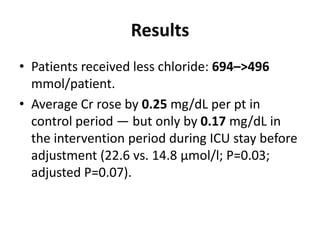

The document discusses a study on the effects of chloride-restrictive intravenous (IV) fluids versus chloride-rich saline solutions in the ICU, indicating that the former significantly decreased the incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) and the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT). The study involved a before-and-after pilot design comparing patient outcomes before and after implementing the chloride-restrictive strategy. While no differences were observed in mortality or hospital stays, the findings raise critical questions about the safety of chloride-rich fluids and suggest the need for further research to confirm these results.

![Results

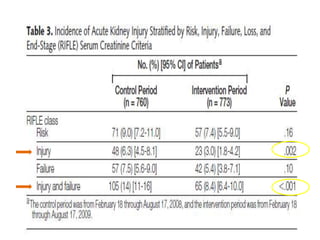

• 10% of pts needed RRT during control v.s.

6.3% during intervention period (p = .005).

• After adjustment for covariates, this

association remained for incidence of injury

and failure class of RIFLE-defined AKI (OR, 0.52

[95% CI, 0.35-0.75]; p<.001) and use of RRT

(OR, 0.52 [95% CI, 0.33-0.81]; p = .004).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalchlorideliberal-130422074401-phpapp01/85/Normal-Saline-is-not-Normal-Chloride-liberal-vs-Chloride-restrictive-IV-Fluid-31-320.jpg)