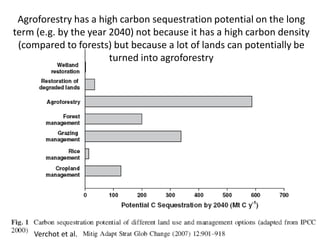

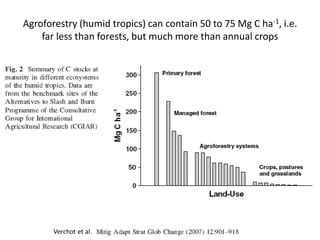

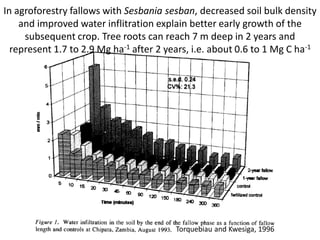

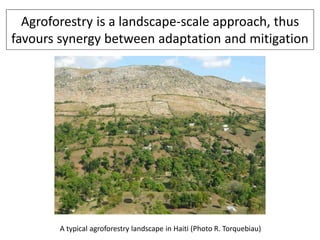

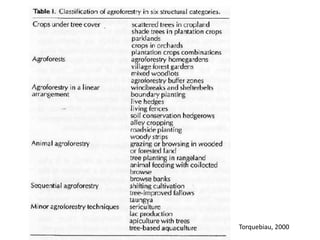

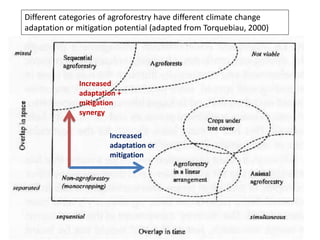

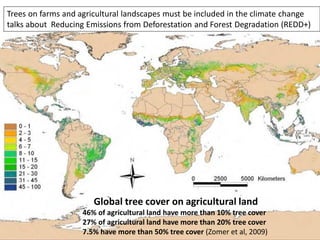

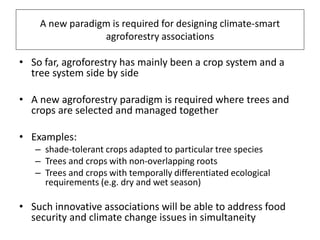

This document summarizes a presentation on agroforestry and climate change. It discusses how agroforestry buffers climate variability and promotes resilience through permanent tree cover and diverse ecological niches. It provides examples of how agroforestry protects soil, increases carbon storage, and allows for different crop types. The document concludes that agroforestry has strong potential for climate change adaptation and mitigation through carbon sequestration and sustainable land management.