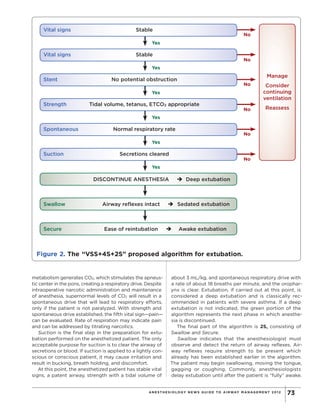

This document proposes a new algorithm for extubating patients called "VSS+4S+2S". It notes that while considerable research has focused on intubation, relatively little attention has been given to developing standardized guidelines and protocols for safe extubation. The proposed algorithm aims to improve extubation practices, minimize failures, and provide a practical framework for teaching residents. It consists of evaluating Vital Signs Stability, then Stent, Strength, Spontaneous breathing, and Suctioning the patient while still under anesthesia. Once these criteria are met, anesthesia is discontinued and the return of Swallowing and ability to Secure the airway are assessed before full extubation. The goal is to establish standardized steps to guide ext