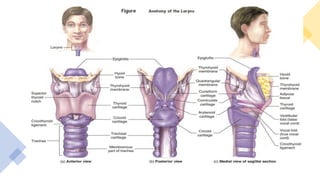

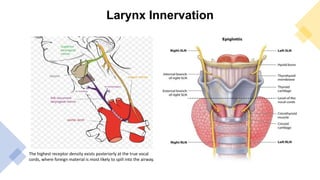

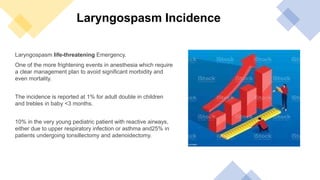

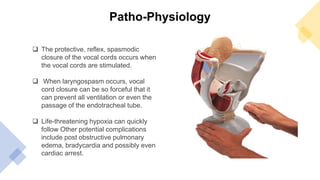

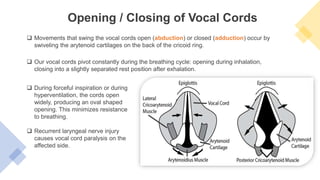

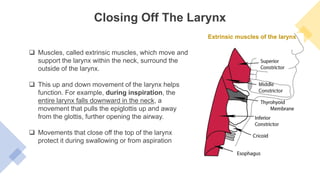

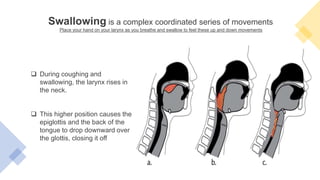

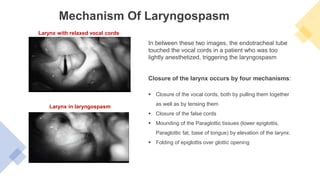

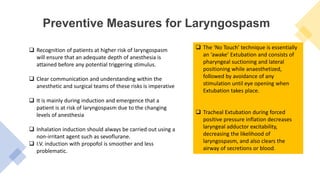

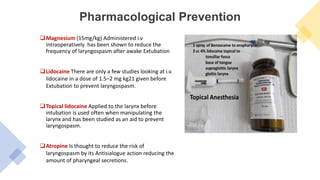

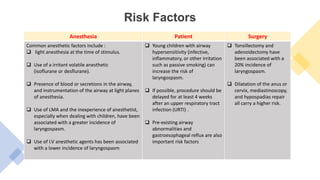

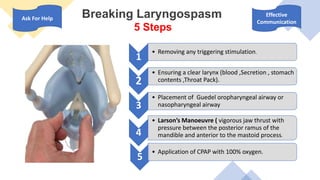

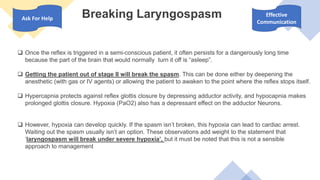

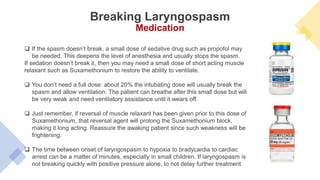

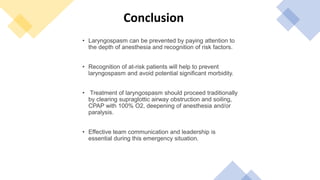

The document discusses laryngospasm, a life-threatening condition characterized by the sustained closure of the vocal cords, primarily occurring during anesthesia. It covers its anatomy, pathophysiology, prevention strategies, risk factors, and management techniques, emphasizing the need for careful monitoring and communication in at-risk patients. Treatment protocols include removing triggering stimuli, ensuring airway clearance, and potentially using pharmacological interventions like magnesium or muscle relaxants to manage the condition.