The document provides information about exercise tolerance tests. Key points include:

1) Exercise tolerance tests evaluate the cardiovascular system's response to exercise under controlled conditions and can detect issues like coronary artery disease.

2) The tests have several purposes like detecting coronary artery disease, evaluating physical capacity, and assessing response to medical interventions.

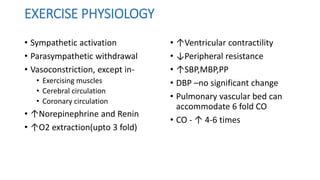

3) There are different types of exercises used in the tests, including isometric, dynamic, and combinations of the two. Dynamic exercise is considered most appropriate for evaluating cardiovascular response.

![AGE PREDICTED MAXIMUM HR

• Age Predicted Max HR= 220 - age in years

• Targeted HR= 85% of Max Predicted HR.

• Maximum HR ↓ with age

• A high degree of variability exists among subjects of identical age

(±12 beats per minute [bpm])

• Not used as an indicator of max exertion in ETT / Indication to

terminate the test](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ettbydr-180826133948/85/Exercise-Tolerance-Test-9-320.jpg)

![Indications for Termination of Exercise Testing

Relative Indications:

• Marked ST displacement (horizontal or downsloping of >2 mm, measured

60 to 80 ms after the J point [the end of the QRS complex]) in a patient

with suspected ischemia

• Drop in systolic blood pressure >10 mm Hg (persistently below baseline)

despite an increase in workload, in the absence of other evidence of

ischemia

• Increasing chest pain

• Fatigue, shortness of breath, wheezing, leg cramps, or claudication

• Arrhythmias other than sustained VT, including multifocal ectopy,

ventricular triplets, supraventricular tachycardia, and bradyarrhythmias

that have the potential to become more complex or to interfere with

hemodynamic stability

• Exaggerated hypertensive response (systolic blood pressure >250 mm Hg or

diastolic blood pressure >115 mm Hg)

• Development of bundle-branch block that cannot immediately be

distinguished from VT](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ettbydr-180826133948/85/Exercise-Tolerance-Test-20-320.jpg)