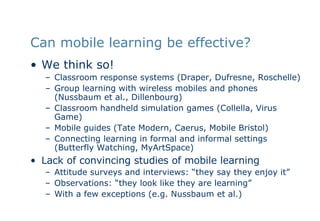

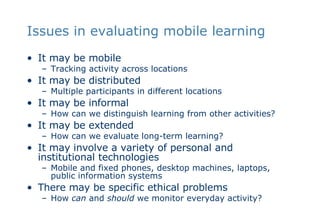

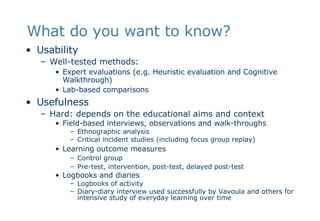

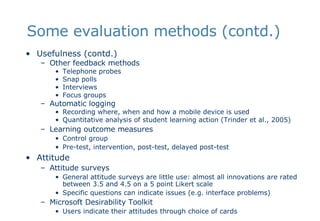

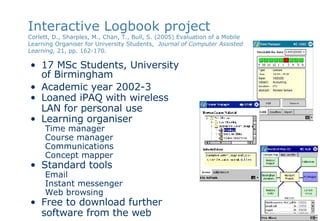

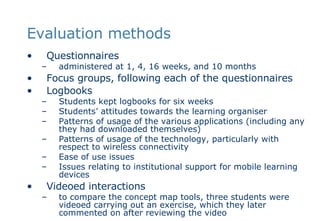

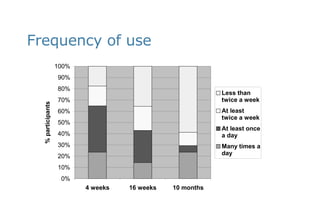

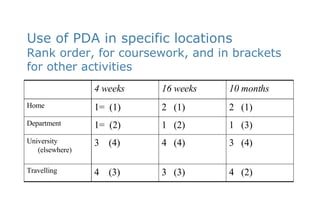

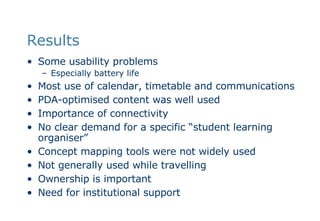

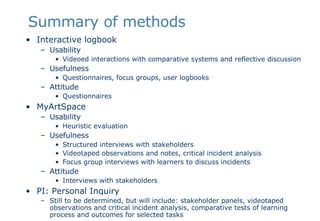

The document discusses various methods for evaluating mobile learning. It describes studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of mobile technologies for classroom response systems, group learning, simulations, and connecting formal and informal learning. It notes challenges in evaluating mobile learning given its mobile, distributed, informal, and extended nature. The document then provides details on evaluation methods for usability, usefulness, attitudes, and case studies that have utilized questionnaires, interviews, observations, logbooks, and video recordings.