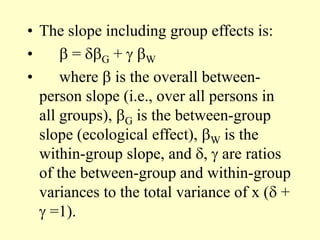

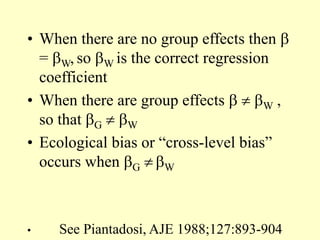

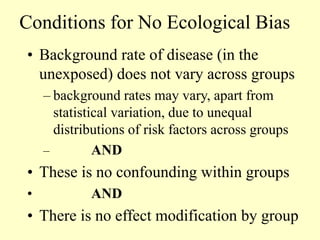

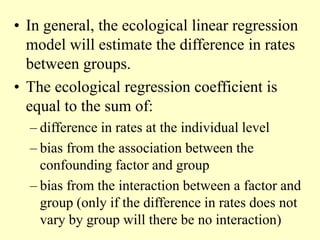

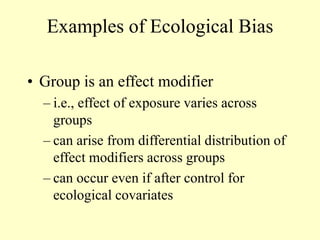

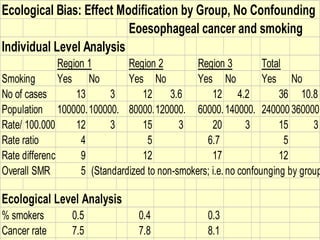

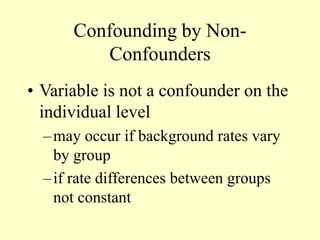

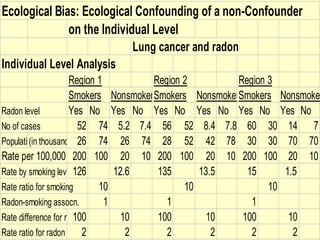

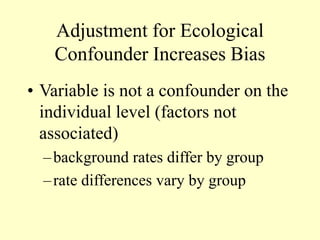

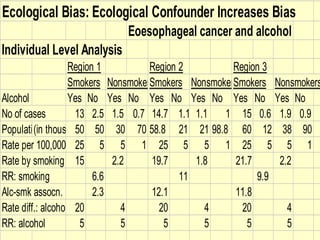

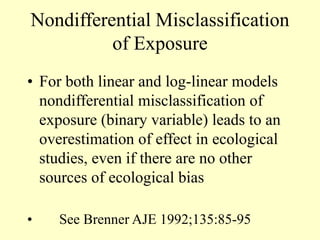

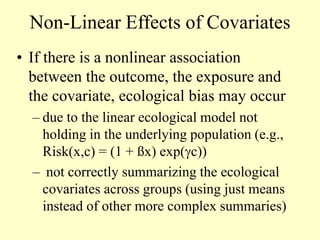

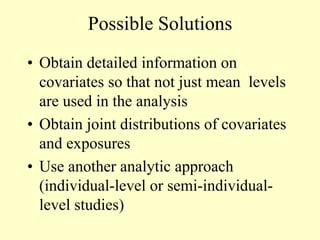

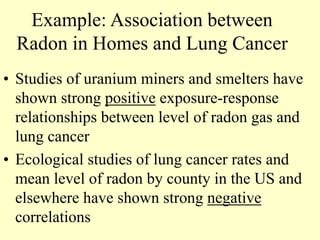

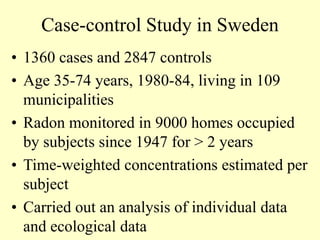

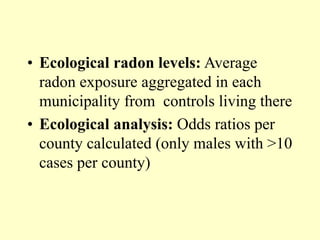

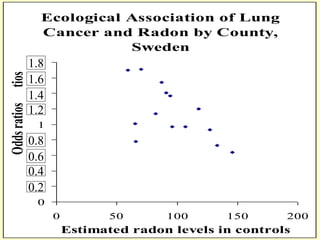

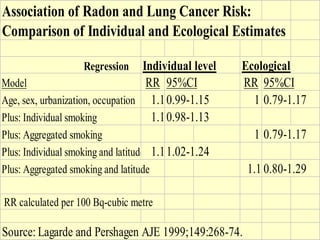

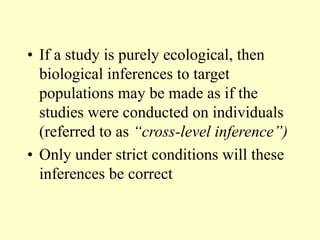

This document discusses ecological studies, which investigate the distribution of health outcomes and their determinants between groups rather than individuals. While individual-level data may not be available, ecological studies can still provide useful information. However, inferences made from ecological data to individuals may be biased due to factors varying between groups like background rates, confounding, or effect modification. Conditions where ecological bias does not occur include no variation in background rates or effects between groups. Solutions proposed to address ecological bias include obtaining more detailed covariate data or conducting individual-level studies. The document provides examples of potential biases and compares individual versus ecological estimates using a study of radon exposure and lung cancer risk.

![Ecological Fallacy

• Assumptions:

–1) that the effects estimated at the

individual level are the relevant ones

for making biological inferences

–2) that the effects are a linear

function of the predictors; i.e. E[yi] =

+ xi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ecologicalstudy-240217102801-31e3d3d4/85/ecological-study-powerpoint-presentation-15-320.jpg)

![• Assume the above relationship {E[yi] =

+ xi} to hold on an individual level

and that the parameter of interest for

the purposes of biological inference is

.

• Assume now that the population is

segregated into groups and that the

analysis proceeds by comparing the

grouped mean between the k groups

(no individual data available).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ecologicalstudy-240217102801-31e3d3d4/85/ecological-study-powerpoint-presentation-16-320.jpg)