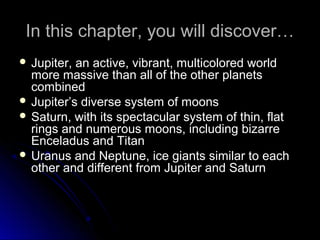

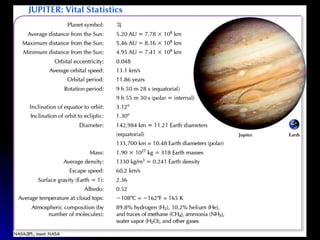

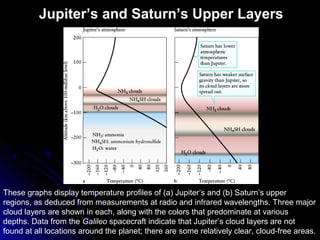

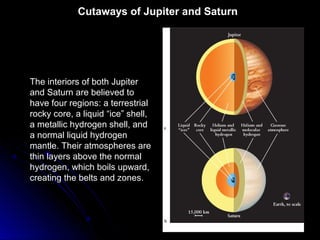

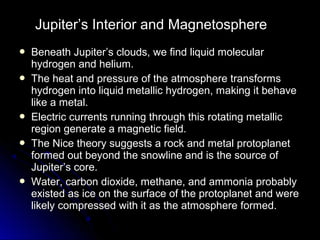

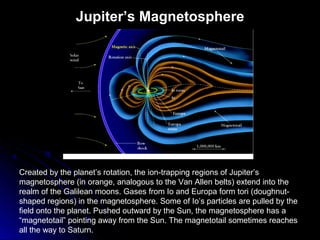

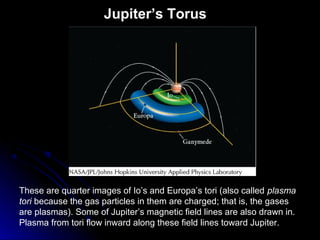

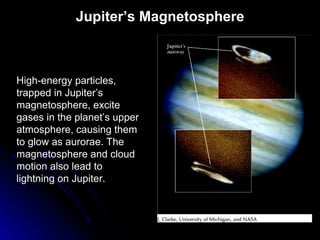

- Jupiter is the largest planet in the solar system and has a diverse system of moons. Its atmosphere is made up of hydrogen and helium and has colorful cloud bands. Beneath the clouds is liquid metallic hydrogen which generates Jupiter's strong magnetic field.

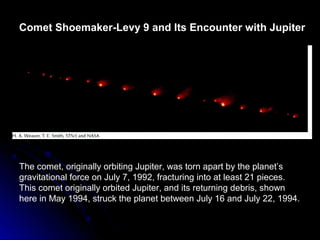

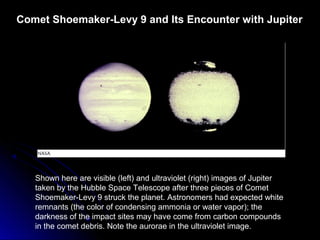

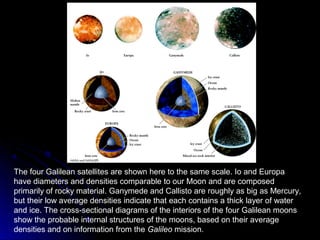

- The document discusses Jupiter's atmosphere, interior structure, magnetic field, and its 67 moons including the four largest Galilean moons. It also describes impacts on Jupiter from comet Shoemaker-Levy 9.