The document discusses the integration of digital technologies in language learning and teaching, emphasizing the importance of adapting educational practices to leverage new technology effectively. It explores various factors affecting technology use, including the

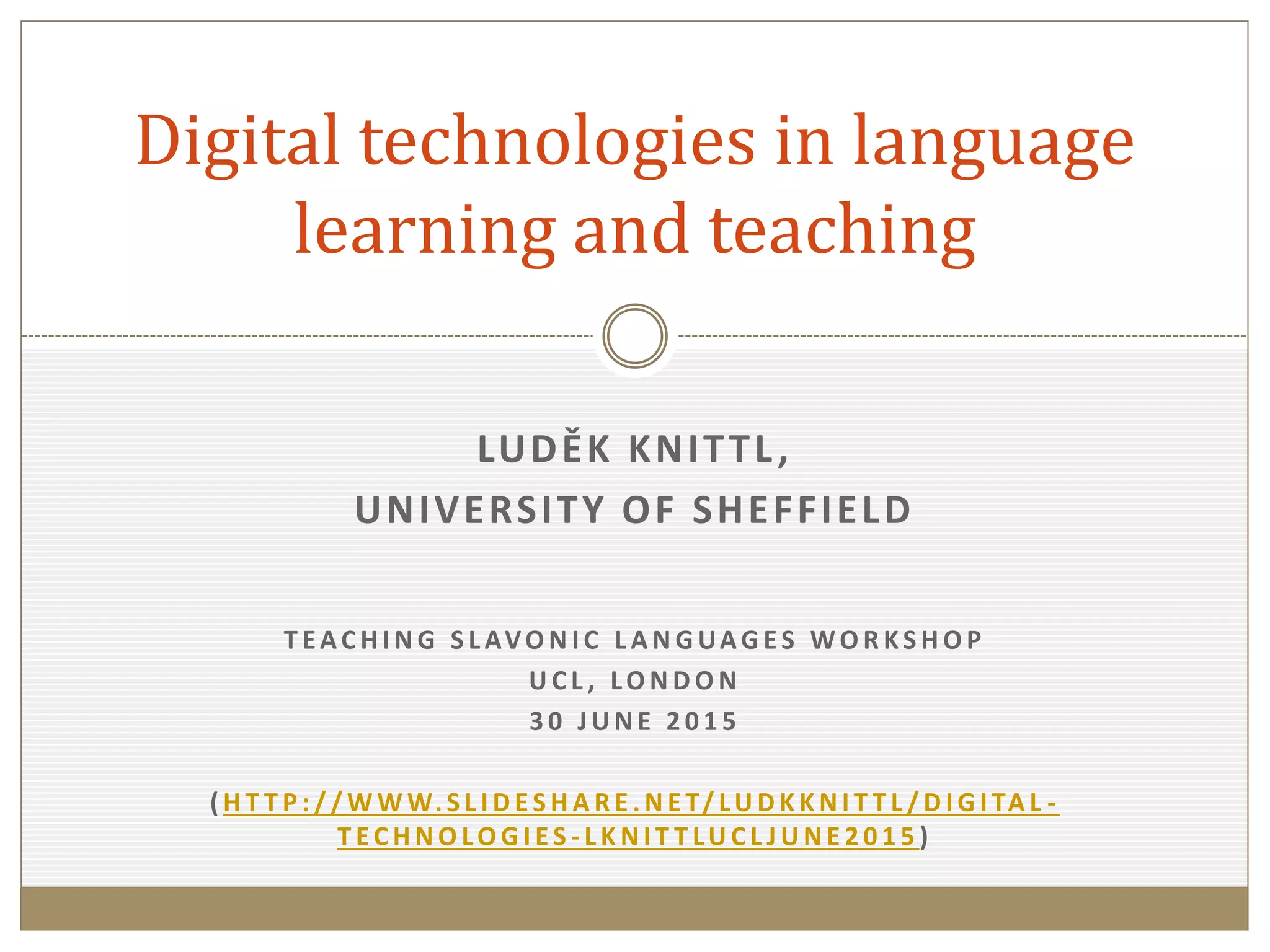

![A successful solution?

VLEs work best when set up as a well-organised hub

containing some materials but also links to other resources.

“You can't use [the VLE] on its own. You teach students that

there are links to exercises, grammars etc. and you point them

to it.” (Teacher)

“It works for [one language] because everything is there and

you can find everything. It's ok to link to something else

because it's well organised.” (Student)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitaltechnologies-l-knittl-ucl-june2015-150629112832-lva1-app6891/85/Digital-technologies-in-language-learning-and-teaching-16-320.jpg)

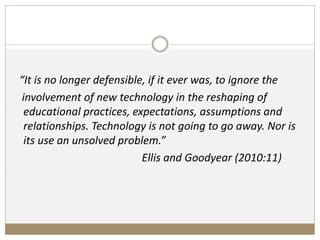

![Disadvantages

•Less control over

contents

•Can be unreliable

•Less accessible to

beginner students

Advantages

•Quantity and variety

•Real-life language

•Supporting learner

autonomy

Using tools other than VLEs

“Sometimes we get links to things for Dutch and there is the

Dutch grammar website [not hosted by the university] but that

never works.” (Student)

“Our Russian textbooks have extensive websites but they are

mostly traditional static resources. There are some interactive

exercises.” (Teacher)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitaltechnologies-l-knittl-ucl-june2015-150629112832-lva1-app6891/85/Digital-technologies-in-language-learning-and-teaching-18-320.jpg)

![References

Jisc (2014) Use of VLEs with Digital Media. [Online] Available from:

http://www.jiscdigitalmedia.ac.uk/guide/introduction-to-the-use-of-vles-with-digital-media

Knittl, L. (2014) Technologies in language learning and teaching: barriers and opportunities,

MEd dissertation, University of Sheffield, unpublished.

Kopcha, T.J. (2012) Teachers’ perceptions of the barriers to technology integration and

practices with technology under situated professional development. Computers and

Education, 59(1109-1121).

Njenga, J.K. and Fourie, L.C.H. (2010) The myths about e-learning in higher education.

British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(2), 199-212.

Margaryan, A., Littlejohn, A. & Vojt, G. (2011) Are digital natives a myth or reality?

University studets’ use of digital technologies. Computers & Education, 56, 429-440.

Oblinger, D., & Oblinger, J. (2005). Is it age or IT: first steps towards understanding the net

generation. In D. Oblinger, & J. Oblinger (Eds.), Educating the Net Generation (pp. 2.1–2.20).

Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE, Online: http://www.educause.edu/research-and-

publications/books/educating-net-generation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitaltechnologies-l-knittl-ucl-june2015-150629112832-lva1-app6891/85/Digital-technologies-in-language-learning-and-teaching-25-320.jpg)

![References

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9

(5), 1–6. Available online at:

http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-

%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

Puentedura, R.R. (2014) Learning, Technology, and the SAMR Model:

Goals, Processes, and Practice [Online] Available from:

http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2014/06/29/LearningTech

nologySAMRModel.pdf

Sharpe, R. and Benfield, G. (2014) Reflections on ‘The student experience

of e-learning in higher education: a review of the literature’. Brookes

eJournal of Learning and Teaching, 6(1).

Steel, C.H. and Levy, M. (2013) Language students and their technologies:

Charting the evolution 2006–2011. ReCALL, 25(3), 306-320.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitaltechnologies-l-knittl-ucl-june2015-150629112832-lva1-app6891/85/Digital-technologies-in-language-learning-and-teaching-26-320.jpg)