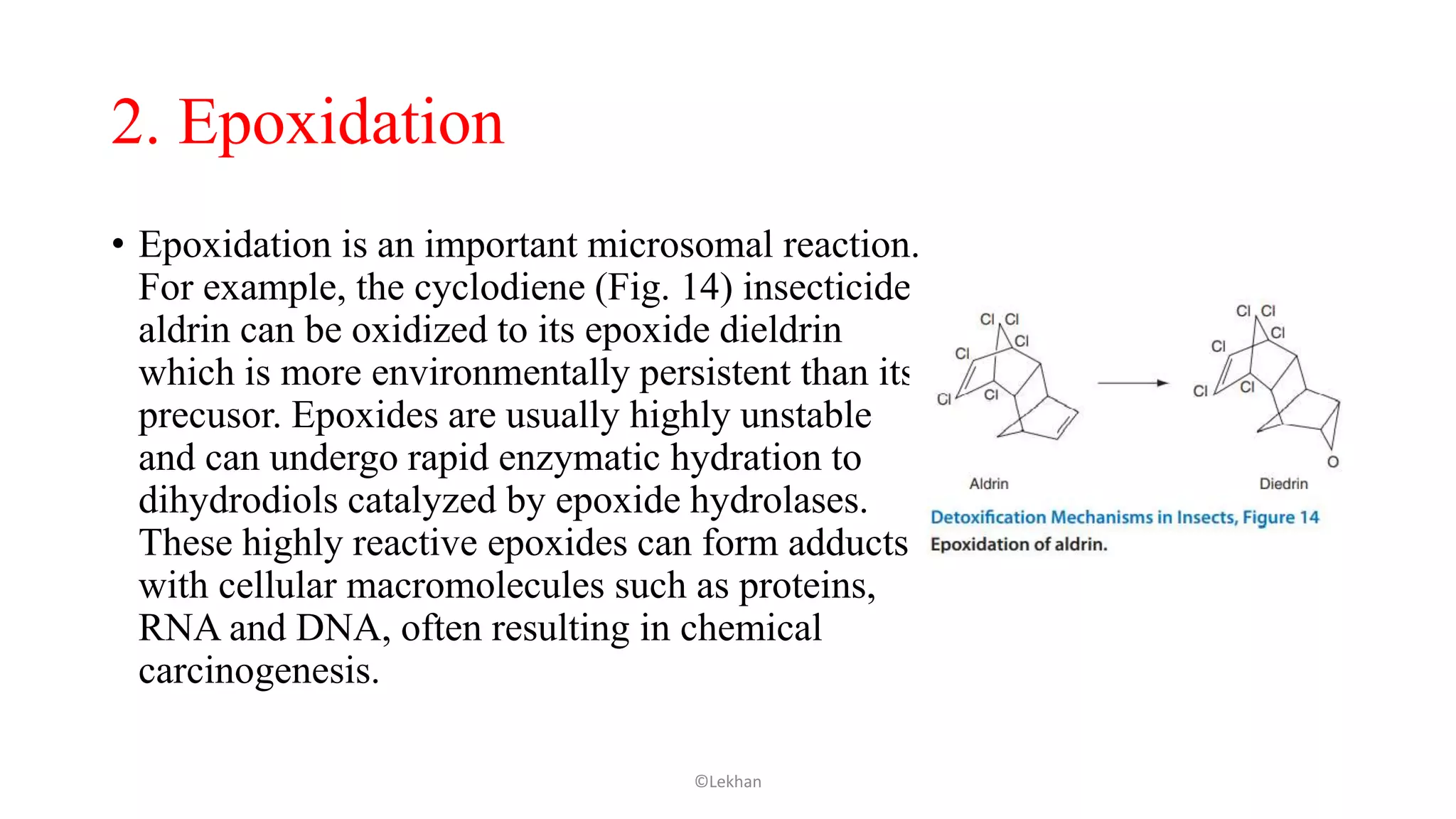

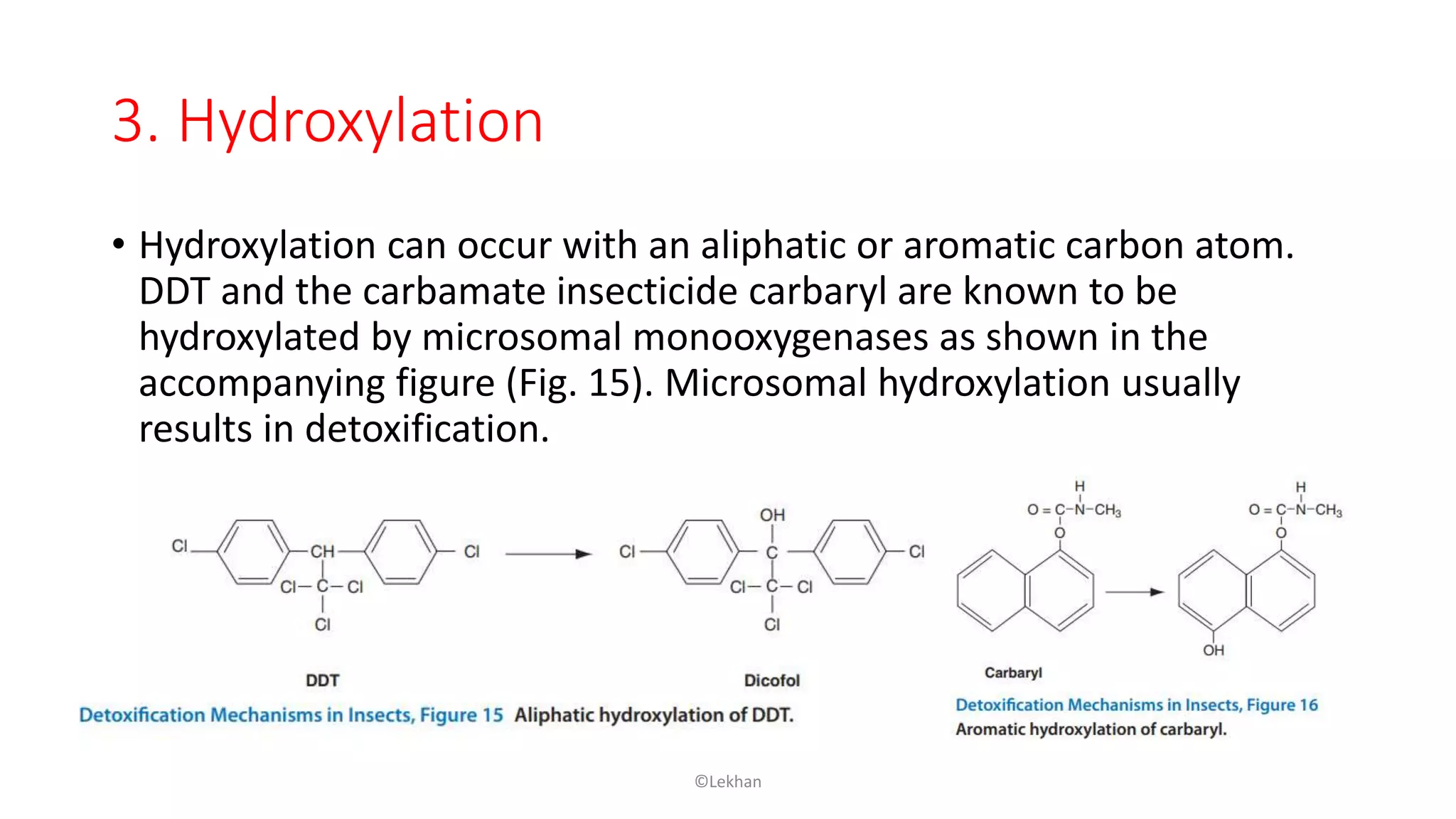

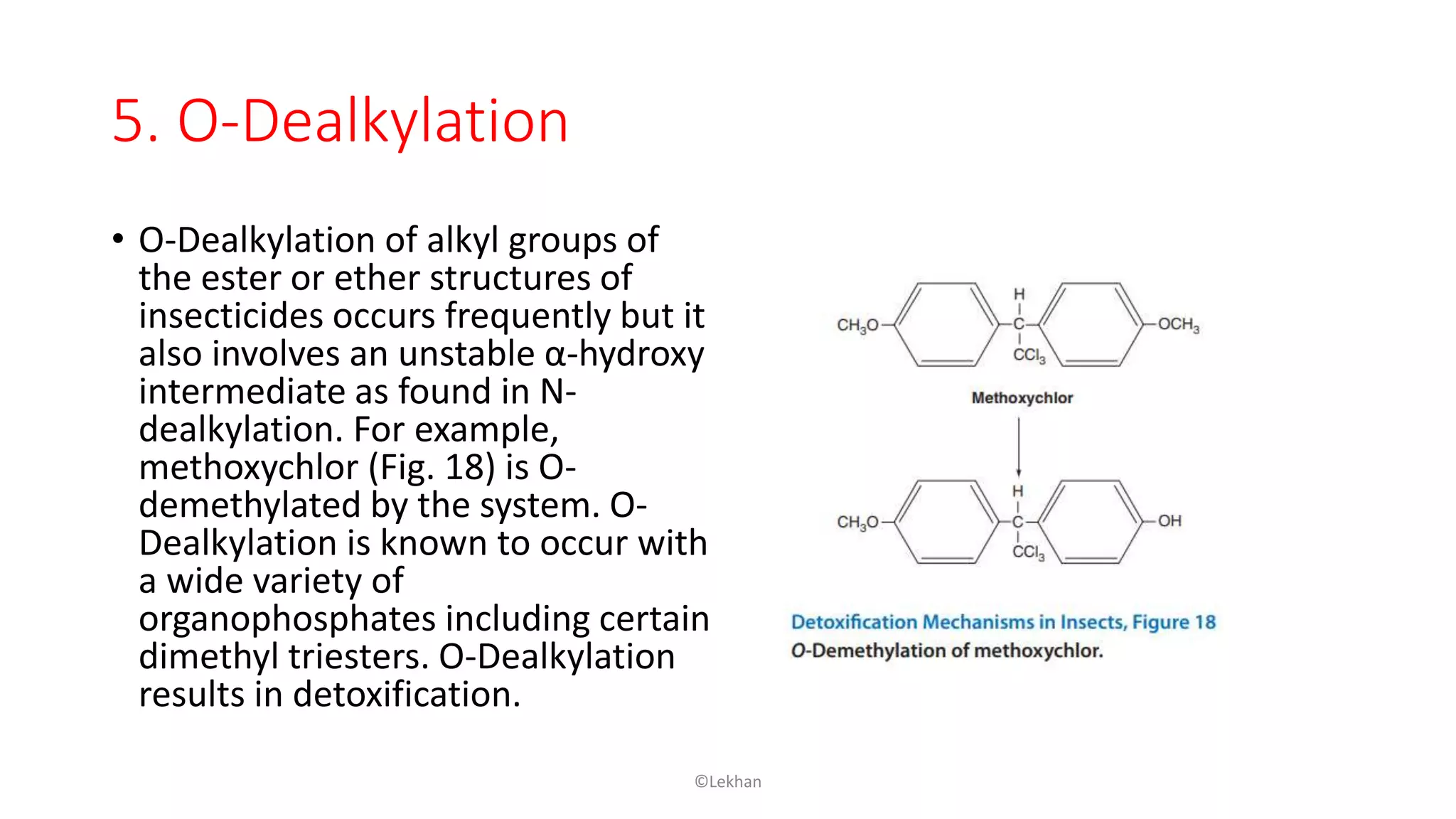

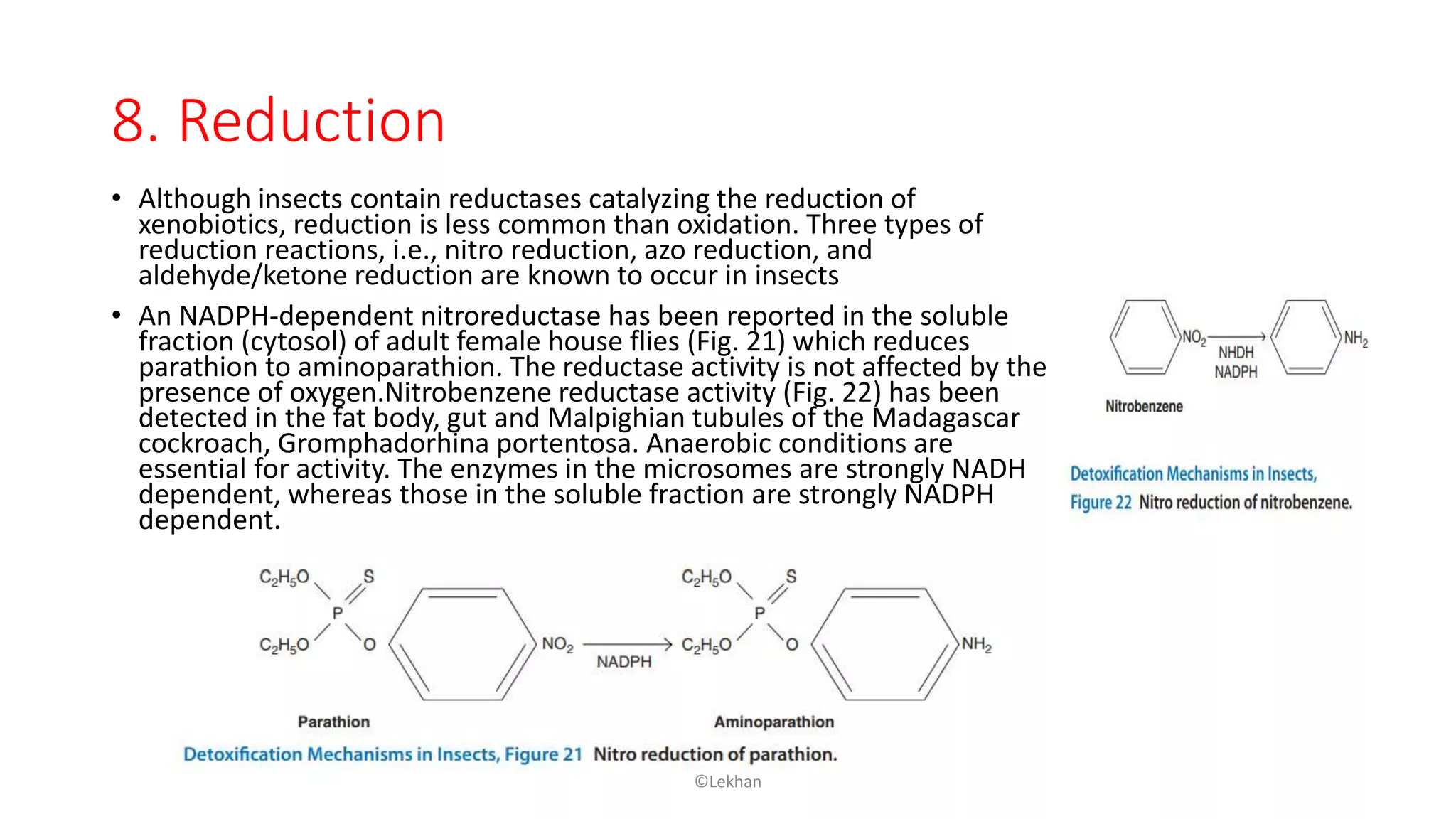

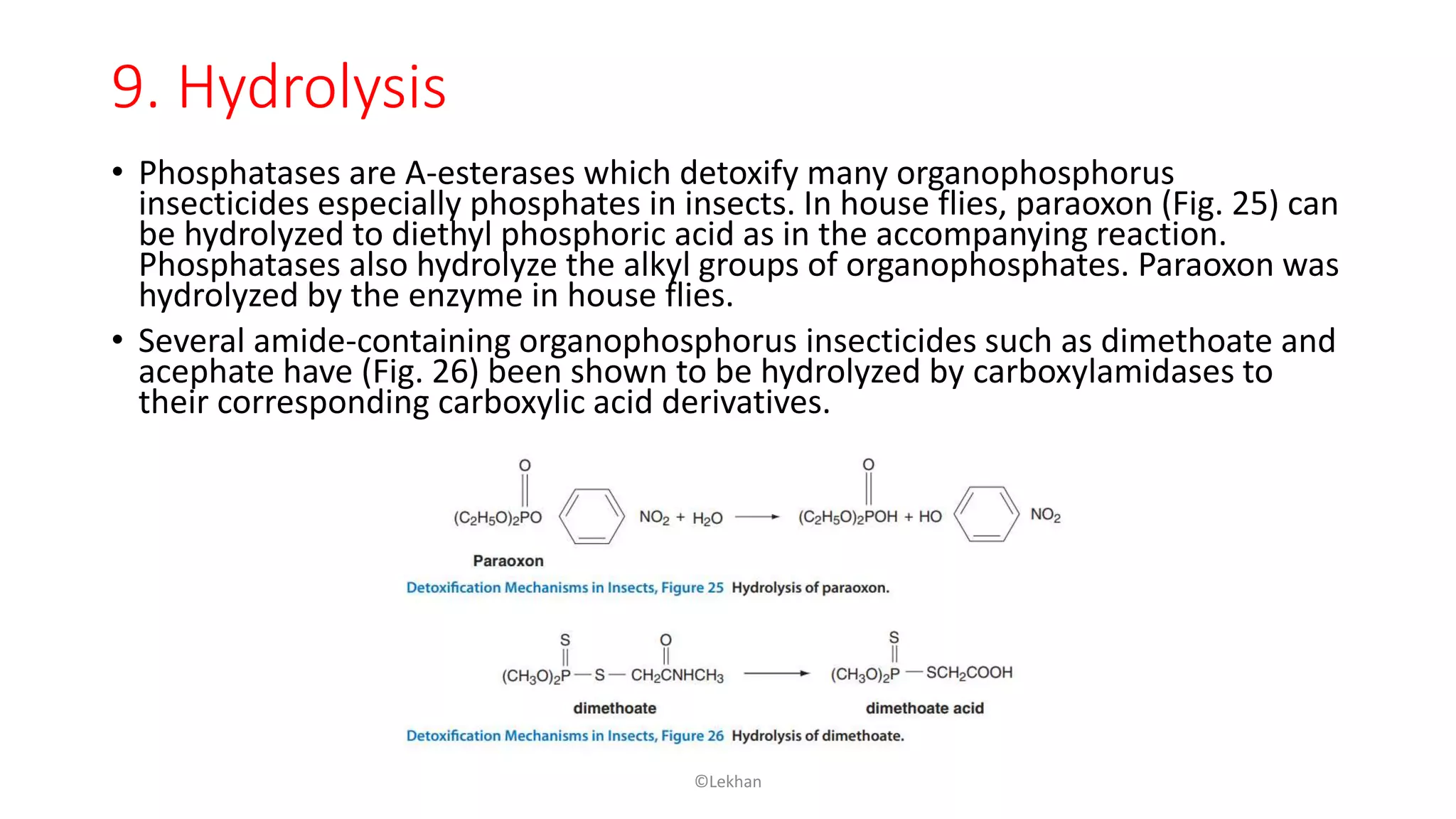

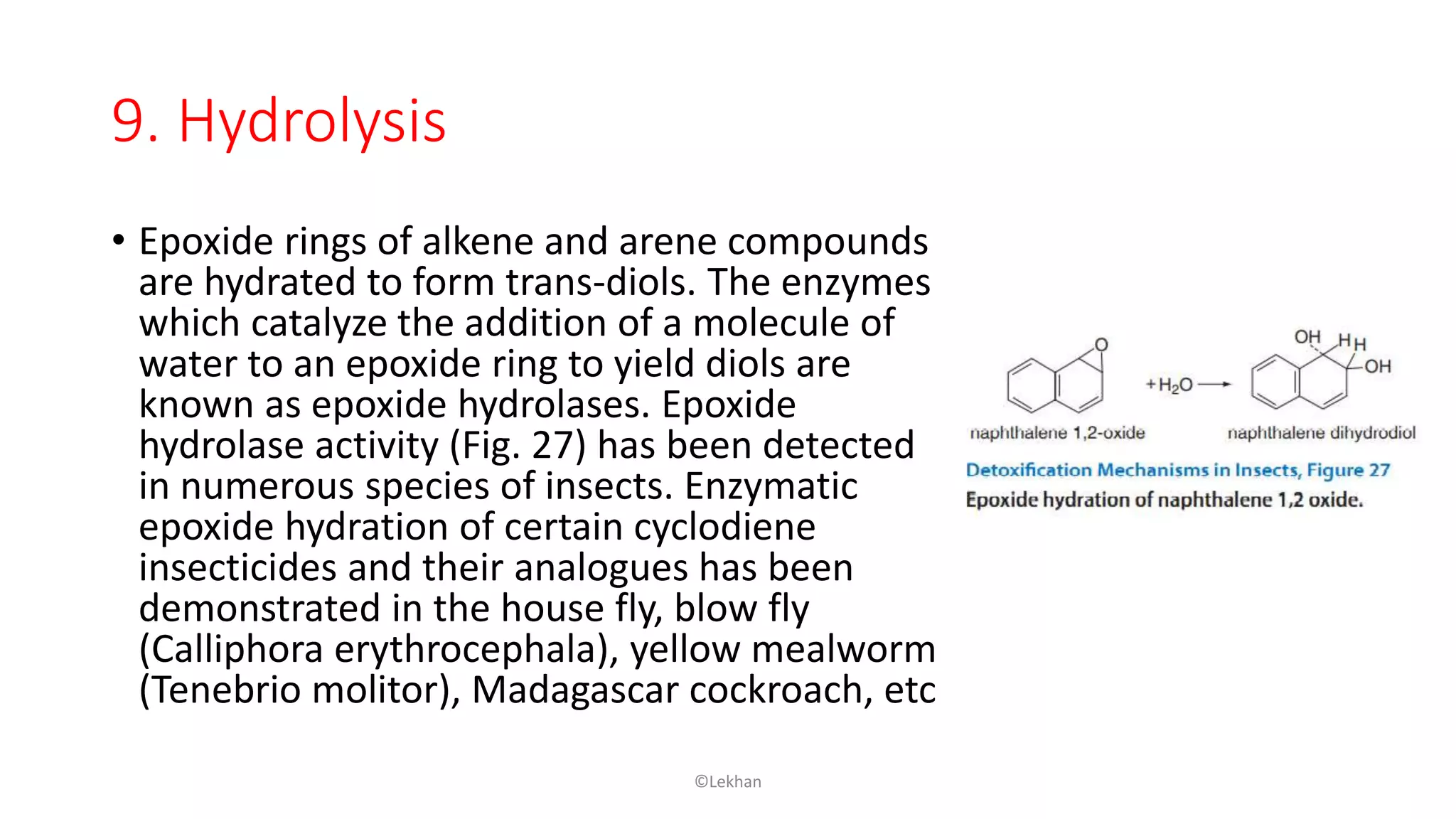

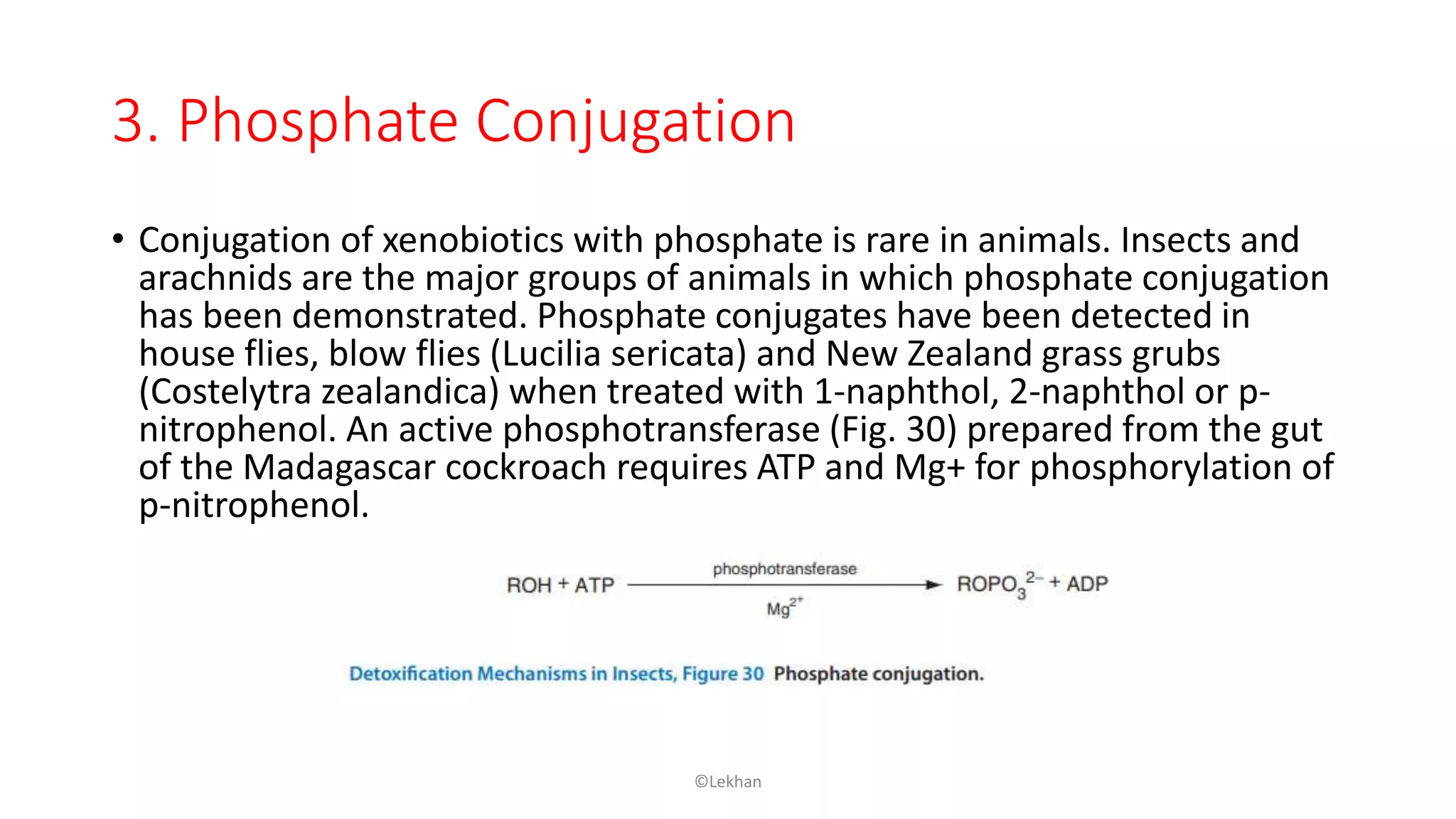

Insects have evolved various detoxification mechanisms to survive natural toxins and overcome insecticides. These mechanisms include phase I reactions like oxidation, reduction, and hydrolysis as well as phase II conjugation reactions like glucose, sulfate, phosphate, amino acid, and glutathione conjugation. Detoxification enzymes in insects can also be induced in response to chemical stress from insecticides, hormones, and allelochemicals to increase an insect's ability to metabolize and remove toxins from the body.

![1. Oxidation

• The oxidative reactions are carried out by a group of enzymes called

microsomal cytochrome P450 monooxygenases [also known as

mixed-function oxidases (MFO) or microsomal oxidases]. These

enzymes, located in the endoplasmic reticulum of eukaryotic cells,

commonly are found in mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, crustaceans,

molluscs, insects, bacteria, yeast and higher plants. Microsomal

monooxygenases are a three-component system comprised of

cytochrome P450, NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase and a

phospholipid (phosphatidylcholine)

©Lekhan](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/detoxificationmechanismsin-210622173550/75/Detoxification-mechanisms-in-Insects-5-2048.jpg)

![• The details of catalytic events mediated by cytochrome P450 are not fully understood. The

substrate first binds to oxidized cytochrome P450 (Fe3+); the enzyme-substrate complex

undergoes reduction and then interacts with oxygen. Finally, the hydroxylated substrate and a

molecule of water are released. Electrons from NADPH are transported by NADPH-

cytochrome P450 reductase and provide reducing equivalents to the ferric cytochrome P450-

substrate complex.

• where RH is a substrate. In some cases, the second electron may originate from NADH via

cytochrome b5. Cytochrome b5is involved in fatty acid desaturation and in certain

microsomal monooxygenase activities, including methoxycoumarin O-demethylation,

ethoxycoumarin deethylation, benzo[a]pyrene hydroxylation and cypermethrin hydroxylation

in house flies

• To date, several hundred cytochrome P450 genes have been identified, including the house fly

(CYP6A1, CYP6A3, CYP6A4, CYP6A5, CYP6C1, CYP6D1), the pomace fly (CYP6A2,

CYP4D1, CYP4D2, CYP4E1), the bollworm, Helicoverpa amigera (CYP6B2, CYP4G8,

CYP9A3, CYP6B2), the tobacco budworm, Heliothis virescens (CYP9A1), the black

swallowtail (CYP6B1, CYP6B3)

©Lekhan](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/detoxificationmechanismsin-210622173550/75/Detoxification-mechanisms-in-Insects-6-2048.jpg)