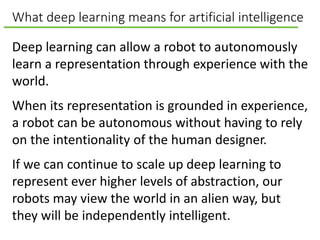

This document provides an overview of deep learning and its applications. It discusses how deep learning uses neural networks with many layers to learn representations of data, such as images and text, in an automated way. For computer vision, deep learning has made major improvements in tasks like object recognition, surpassing human-level performance. Deep learning has also been applied successfully to natural language processing tasks like learning word embeddings. The document suggests deep learning is an important development for achieving more broadly intelligent artificial systems.

![AI through the lens of System 1 and System 2

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman in Thinking Fast and Slow describes

humans as having two modes of thought: System 1 and System 2.

System 1: Fast and Parallel System 2: Slow and Serial

AI systems in these domains are useful

but limited. Called GOFAI (Good, Old-

Fashioned Artificial Intelligence).

1. Search and planning

2. Logic

3. Rule-based systems

Subconscious: E.g., face recognition or

speech understanding.

Conscious: E.g., when listening to a

conversation or making PowerPoint slides.

We underestimated how hard it would

be to implement. E.g., we thought

computer vision would be easy.

We assumed it was the most difficult.

E.g., we thought chess was hard.

This has changed

1. We now have GPUs and

distributed computing

2. We have Big Data

3. We have new algorithms [Bengio et

al., 2003; Hinton et al., 2006; Ranzato et

al., 2006]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-3-320.jpg)

![Three-layered neural network

A bunch of neurons chained together is called a neural network.

Layer 2: hidden layer. Called

this because it is neither input

nor output.

[16.2, 17.3, −52.3, 11.1]

Layer 3: output. E.g., cat

or not a cat; buy the car or

walk.

Layer 1: input data. Can

be pixel values or the number

of cup holders.

This network has three layers.

(Some edges lighter

to avoid clutter.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-7-320.jpg)

![Training with supervised learning

Supervised Learning: You show the network a bunch of things

with a labels saying what they are, and you want the network to

learn to classify future things without labels.

Example: here are some

pictures of cats. Tell me

which of these other pictures

are of cats.

To train the network, want to

find the weights that

correctly classify all of the

training examples. You hope

it will work on the testing

examples.

Done with an algorithm

called Backpropagation

[Rumelhart et al., 1986].

[16.2, 17.3, −52.3, 11.1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-8-320.jpg)

![Deep learning is adding more layers

There is no exact

definition of

what constitutes

“deep learning.”

The number of

weights (parameters)

is generally large.

Some networks have

millions of parameters

that are learned.

[16.2, 17.3, −52.3, 11.1]

(Some edges omitted

to avoid clutter.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-9-320.jpg)

![Recall our standard architecture

Layer 2: hidden layer. Called

this because it is neither input

nor output.

Layer 3: output. E.g., cat

or not a cat; buy the car or

walk.

Layer 1: input data. Can

be pixel values or the number

of cup holders.

[16.2, 17.3, −52.3, 11.1]

Is this a cat?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-12-320.jpg)

![Neural nets with multiple outputs

Okay, but what kind of cat is it?

𝑃(𝑥)

[16.2, 17.3, −52.3, 11.1]

𝑃 𝑜𝑖 =

𝑒 𝑠𝑢𝑚(𝑥 𝑖)+𝑏 𝑖

𝑗 𝑒 𝑠𝑢𝑚 𝑥 𝑗 +𝑏 𝑗

𝑃(𝑥)𝑃(𝑥) 𝑃(𝑥) 𝑃(𝑥)

Introduce a new node

called a softmax.

Probability a

house cat

Probability a

lion

Probability a

panther

Probability a

bobcat

Where 𝑗 varies over all the

other nodes at that layer.

Just normalize the output 𝑜𝑖

over the sum of the other

outputs.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-13-320.jpg)

![Learning word vectors

13.2, 5.4, −3.1 [−12.1, 13.1, 0.1] [7.2, 3.2,-1.9]

the man ran

From the sentence, “The man ran fast.”

𝑃(𝑥)𝑃(𝑥) 𝑃(𝑥) 𝑃(𝑥)

Probability

of “fast”

Probability

of “slow”

Probability

of “taco”

Probability

of “bobcat”

Learns a vector for each word based on the “meaning” in the sentence by

trying to predict the next word [Bengio et al., 2003].

Computationally

expensive because you

need a softmax

node for each word in

the vocabulary.

Recent work models the top

layer using a binary tree

[Mikolov et al., 2013].

These numbers updated

along with the weights

and become the vector

representations of the

words.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-14-320.jpg)

![Comparing vector and symbolic representations

Vector representation

taco = [17.32, 82.9, −4.6, 7.2]

Symbolic representation

taco = 𝑡𝑎𝑐𝑜

• Vectors have a similarity score.

• A taco is not a burrito but similar.

• Symbols can be the same or not.

• A taco is just as different from a

burrito as a Toyota.

• Vectors have internal structure

[Mikolov et al., 2013].

• Italy – Rome = France – Paris

• King – Queen = Man – Woman

• Symbols have no structure.

• Symbols are arbitrarily assigned.

• Meaning relative to other symbols.

• Vectors are grounded in

experience.

• Meaning relative to predictions.

• Ability to learn representations

makes agents less brittle.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-15-320.jpg)

![Learning vectors of longer text

[33.1, 7.5, 11.2] 13.2, 5.4, −3.1 [−12.1, 13.1, 0.1] [7.2, 3.2,-1.9]

<current paragraph> the man ran

From the sentence, “The man ran fast.”

𝑃(𝑥)𝑃(𝑥) 𝑃(𝑥) 𝑃(𝑥)

Probability

of “fast”

Probability

of “slow”

Probability

of “taco”

Probability

of “bobcat”

The “meaning” of a

paragraph is encoded in

a vector that allows you

to predict the next word

in the paragraph using

already learned word

vectors [Le and Mikolov,

2014].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-16-320.jpg)

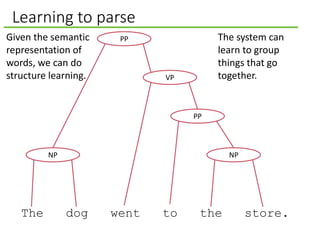

![Learning to parse

[1.1,1.3] [8.1, 2.1] [2.6, 8.4] [2.0, 7.1] [8.9, 2.4] [7.1, 2.2]

[1.1, 1.3] [1.1, 1.3]

[7.3, 9.8]

[3.2, 8.8]

[9.1, 0.2]Given the semantic

representation of

words we can do

structure learning.

Socher et al. [2010]

learned word

vectors and then

used the Penn Tree

Bank to train a

parser that

encodes semantic

meaning.

The dog went to the store.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-18-320.jpg)

![Vision is hard

• Even harder for 3D

objects.

• You move a bit, and

everything changes.

72 ⋯ 91

⋮ ⋱ ⋮

16 ⋯ 40

How a computer sees an image.

Example from MNIST

handwritten digit dataset

[LeCun and Cortes, 1998].

Vision is hard because images are big matrices of numbers.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-21-320.jpg)

![Stack up the layers to make a deep network

Input data

Hidden

The output of each layer

becomes the input to the

next layer [Hinton et al.,

2006].

See video starting at

second 45

https://www.coursera.org

/course/neuralnets

0 1 0 1 0 1

0 1 0 1 0 1

Input data

Hidden

0 1 0 1 0 1

0 1 0 1 0 1

Hidden layer becomes

input data of next layer.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-23-320.jpg)

![Computer vision, scaling up

Unsupervised learning was scaled up

by Honglak Lee et al. [2009] to learn

high-level visual features.

[Lee et al., 2009]

Further scaled up by Quoc Le et al.

[2012].

• Used 1,000 machines (16,000

cores) running for 3 days to train 1

billion weights by watching

YouTube videos.

• The network learned to identify

cats.

• The network wasn’t told to look

for cats, it naturally learned that

cats were integral to online

viewing.

• Video on the topic at NYT

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/26/tec

hnology/in-a-big-network-of-computers-

evidence-of-machine-learning.html](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-24-320.jpg)

![Why is this significant?

To have a grounded understanding

of its environment, an agent must

be able to acquire representations

through experience [Pierce et al.,

1997; Mugan et al., 2012].

Without a grounded understanding,

the agent is limited to what was

programmed in.

We saw that unsupervised learning

could be used to learn the meanings of words, grounded in the

experience of reading.

Using these deep Boltzmann machines, machines can learn

to see the world through experience.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-25-320.jpg)

![Limit connections and duplicate parameters

Convolutional neural networks build in

a kind of feature invariance. They take

advantage the layout of the pixels.

[16.2, 17.3, −52.3, 11.1]

With the layers and

topology, our networks are

starting to look a little like

the visual cortex. Although,

we still don’t fully

understand the visual

cortex.

Different areas

of the image go

to different

parts of the

neural network,

and weights are

shared.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-26-320.jpg)

![Recent deep vision networks

ImageNet http://www.image-net.org/ is a huge collection of images

corresponding to the nouns of the WordNet hierarchy. There are hundreds to

thousands of images per noun.

2012 – Deep Learning begins to dominate image recognition

Krizhevsky et al. [2012] got 16% error on recognizing objects, when

before the best error was 26%. They used a convolutional neural

network.

2015 – Deep Learning surpasses human level performance

He et al. [2015] surpassed human level performance on recognizing

images of objects.* Computers seem to have an advantage when the

classes of objects are fine grained, such as multiple species of dogs.

Closing note on computer vision: Hinton points out that modern networks can just

work with top down (supervised learning) if the network is small enough relative to

the amount of the training data; but the goal of AI is broad-based understanding,

and there will likely never be enough labeled training data for general intelligence.

*But deep learning can be easily fooled [Nguyen et al., 2014]. Enlightening video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M2IebCN9Ht4.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-27-320.jpg)

![A stamping in of behavior

When we think of doing things, we think of conscious planning

with System 2.

Imagine trying to get to Seattle.

• Get to the airport. How? Take a taxi. How? Call a taxi. How?

Find my phone.

• Some behaviors arise more from a

a gradual stamping in [Thorndike,

1898].

• Became the study of Behaviorism

[Skinner, 1953] (see Skinner box

on the right).

• Formulated into artificial

intelligence as Reinforcement

Learning [Sutton and Barto, 1998]. By Andreas1 (Adapted from Image:Boite skinner.jpg) [GFDL

(http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via

Wikimedia Commons

A “Skinner box”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-30-320.jpg)

![Playing Atari with Deep Learning

Input, last four frames, where each frame

is downsampled to 84 by 84 pixels.

[Mnih et al., 2013]

represent the

state-action value

function 𝑄 𝑠, 𝑎 as

a convolutional

neural network.

𝑃(𝑥)𝑃(𝑥) 𝑃(𝑥) 𝑃(𝑥)

Value of

moving left

Value of

moving right

Value of

shooting

Value of

reloading

In [Mnih et al., 2013],

this is actually three

hidden layers.

See some videos at

http://mashable.com/2015/02

/25/computer-wins-at-atari-

games/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-34-320.jpg)

![Abstract thinking through image schemas

Humans efficiently generalize experience using abstractions called

image schemas [Johnson, 1987]. Image schemas map experience

to conceptual structure.

Developmental psychologist Jean Mandler argues that some

image schemas are formed before children begin to talk, and that

language is eventually built onto this base set of schemas [2004].

• Consider what it means for an object to contain another object,

such as for a box to contain a ball.

• The container constrains the movement of the object inside.

If the container is moved, the contained object moves.

• These constraints are represented by the container image

schema.

• Other image schemas from Mark Johnson’s book, The Body in the Mind:

path, counterforce, restraint, removal, enablement, attraction, link,

cycle, near-far, scale, part-whole, full-empty, matching, surface, object,

and collection.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-39-320.jpg)

![Abstract thinking through metaphors

Love is a journey. Love is war.

Lakoff and Johnson [1980] argue that we understand abstract

concepts through metaphors to physical experience.

Neural networks will likely require advances in both architecture

and size to reach this level of abstraction.

For example, a container can be more than

a way of understanding physical

constraints, it can be a metaphor used to

understand the abstract concept of what

an argument is. You could say that

someone’s argument doesn’t hold water, or

you could say that it is empty, or you could

say that the argument has holes in it.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearningforartificialintelligence-150312004402-conversion-gate01/85/What-Deep-Learning-Means-for-Artificial-Intelligence-40-320.jpg)