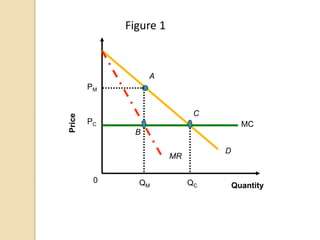

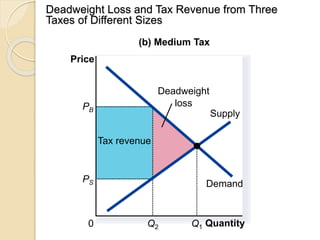

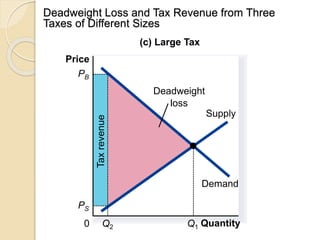

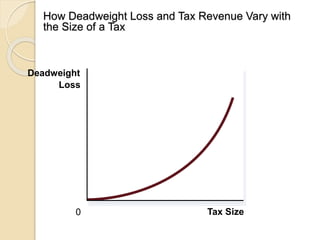

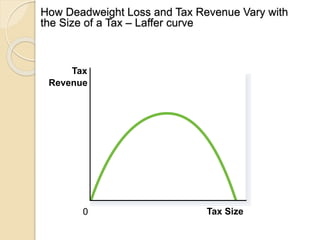

The document discusses deadweight loss that occurs due to taxes and monopolies. It provides the following key points:

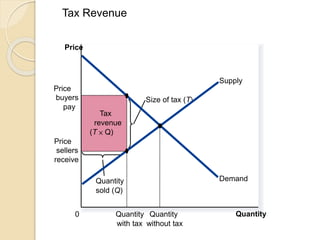

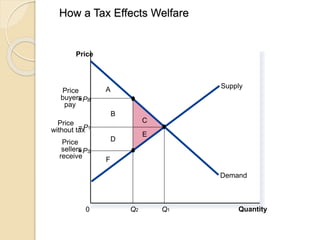

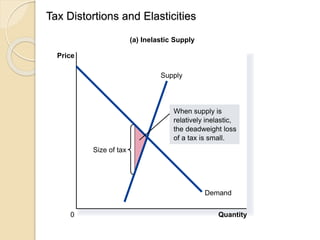

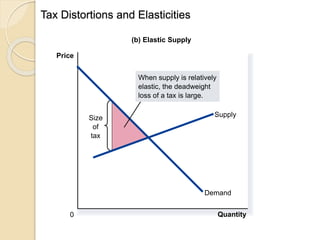

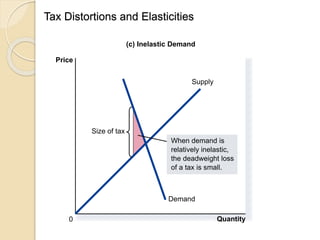

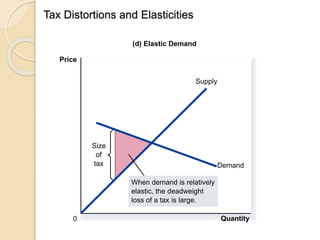

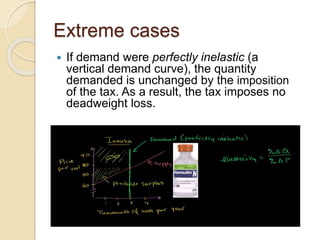

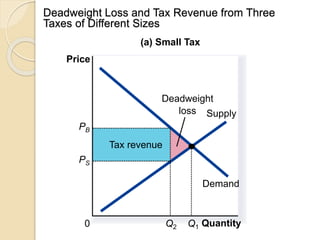

- A tax creates a wedge between the price paid by buyers and received by sellers, resulting in a reduction in quantity traded and deadweight loss for society. The size of the deadweight loss depends on the price elasticities of supply and demand.

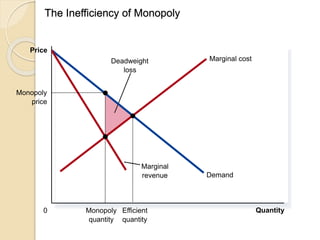

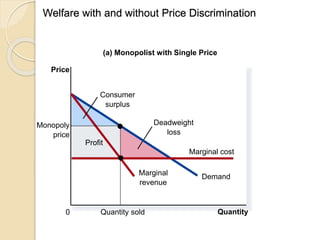

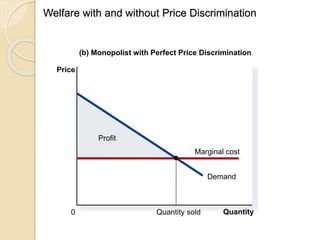

- Monopolies also create deadweight loss by setting price above marginal cost. Price discrimination allows monopolies to reduce deadweight loss by charging different prices to different customers.

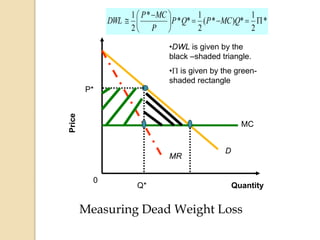

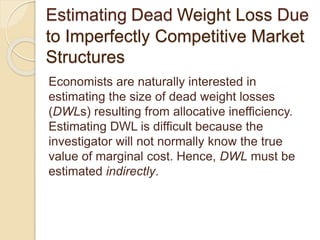

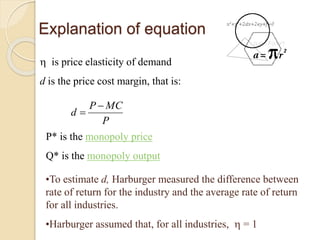

- Estimating deadweight loss is difficult but important for evaluating market efficiency. Two approaches discussed are Harburger's method using industry profit margins and Cowling and Mueller's method

![Harburger’s Approach

The ABH dead weight triangle is approximated by the

following equation (equation 4.1 in the text):

))((

2

1

MCCM QQPPDWL

By algebraic manipulation it can be shown that:

**

2

1 2

QPdDWL [1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deadweightloss-160220182149/85/Dead-weight-loss-33-320.jpg)

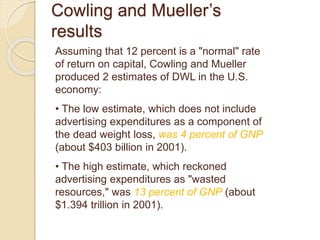

![To estimate industry-level price elasticities (),

Cowling and Mueller took advantage of the fact

that the firm’s profit maximizing price (P*)

satisfies the following condition:

MCP

P

*

* [2]

Recall that d is the price-cost margin . Thus we can

say:

MCP

P

d

*

*1

[3]

Thus by equation [2], we can say:

d

1 Thus if you can

estimate d, you

can estimate ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deadweightloss-160220182149/85/Dead-weight-loss-37-320.jpg)

![Thus substitute 1/d for in equation [1] and you

get:

**

2

1

**

1

2

1 2

QdPQPd

d

DWL

[4]

Substituting (P*- MC)/P* for d in equation [4] gives us:

*

2

1

*)*(

2

1

**

*

2

1

QMCPQP

P

MCP

DWL [5]

Thus, Cowling and Mueller showed that DWL for an

industry was equal to ½ of the economic profits () of

firms in the industry.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deadweightloss-160220182149/85/Dead-weight-loss-38-320.jpg)