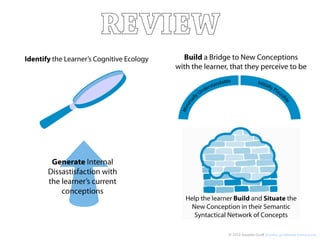

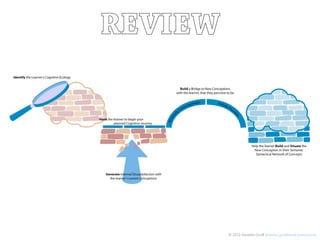

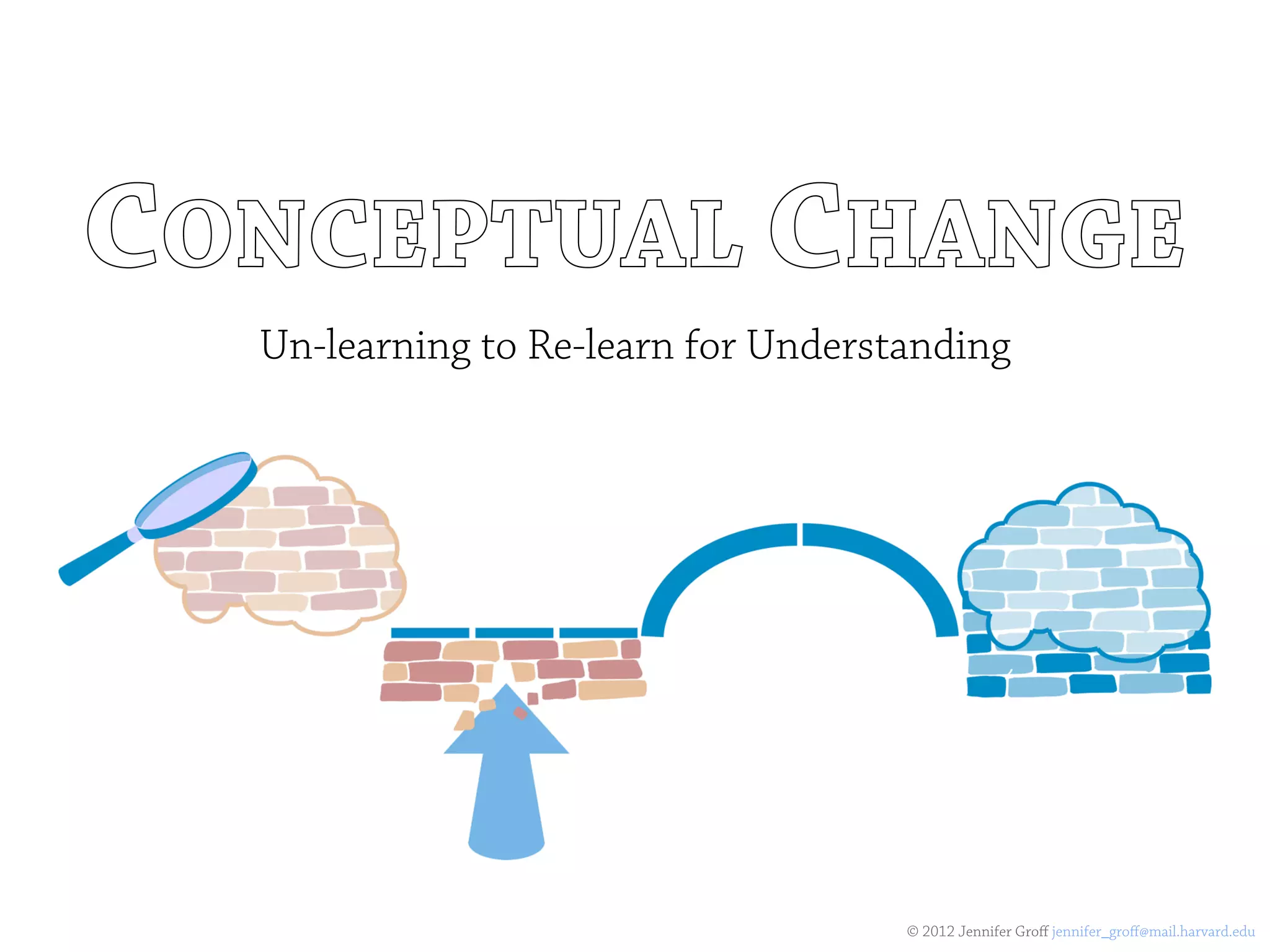

When introducing a new idea to a learner, it must integrate into their existing cognitive framework. This framework is unique to each individual and is resistant to change. To produce a conceptual change, instruction must first identify the learner's current concepts and beliefs. It then needs to create dissatisfaction with their existing conception by exposing weaknesses, anomalies, or new experiences. Finally, the new concept must provide initial understanding and plausibility by relating to their existing knowledge. If successfully integrated into the learner's cognitive network in this way, the new conception can become enduring.

![When a new idea is introduced to a learner, it doesn’t just get

poured into their mind like water into a bucket. e new idea

is faced with integrating itself into the learner’s personal

cognitive landscape.

Each person has their own, unique Cognitive Ecology—

knowledge, concepts, experiences, schemas, and beliefs that

makeup what Kenneth Strike and George Posner call a

“Semantic Syntactical Network of Concepts.” [Hang onto that

notion—we’ll come back to it later]. Generally speaking,

people don’t let go of aspects of their Cognitive Ecology easily

—if a new idea introduced doesn’t fit into their network of

concepts easily (known as ‘assimilation’), then the individual

must alter their network of concepts in order to fit this new

idea into it (or ‘accommodate’ it). It’s kinda like having a

typical two-story home and saying you want to put an indoor

pool in the middle of it—successfully doing so isn’t like just

adding a wing onto the house, instead you’d have to take

apart the whole thing and rebuild it in a new way.

As a result, a person’s current Cognitive Ecology will influence

their production of a new conception.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/conceptualchangegroff-120921133010-phpapp01/85/Conceptual-Change-Unlearn-to-Relearn-2-320.jpg)