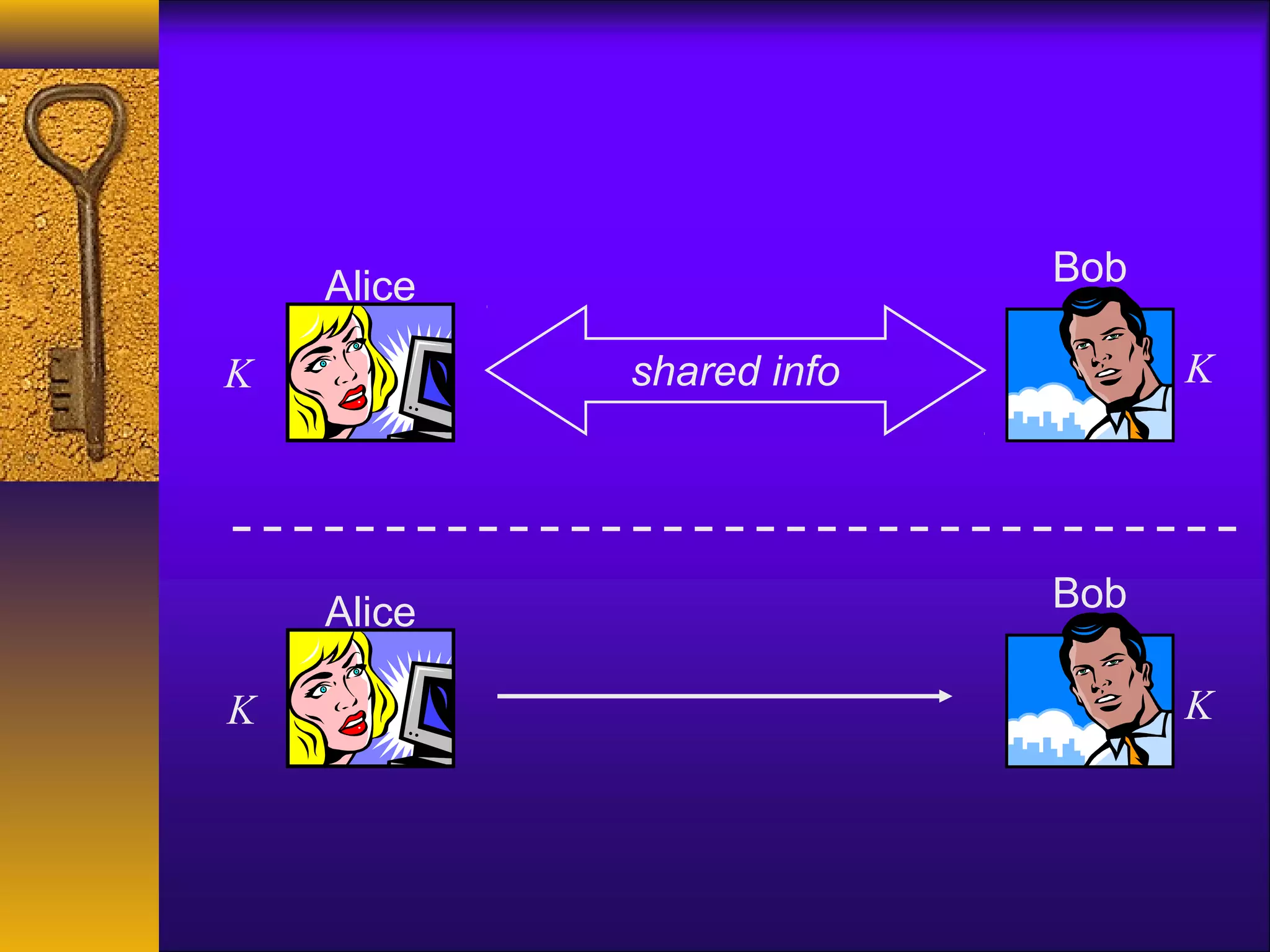

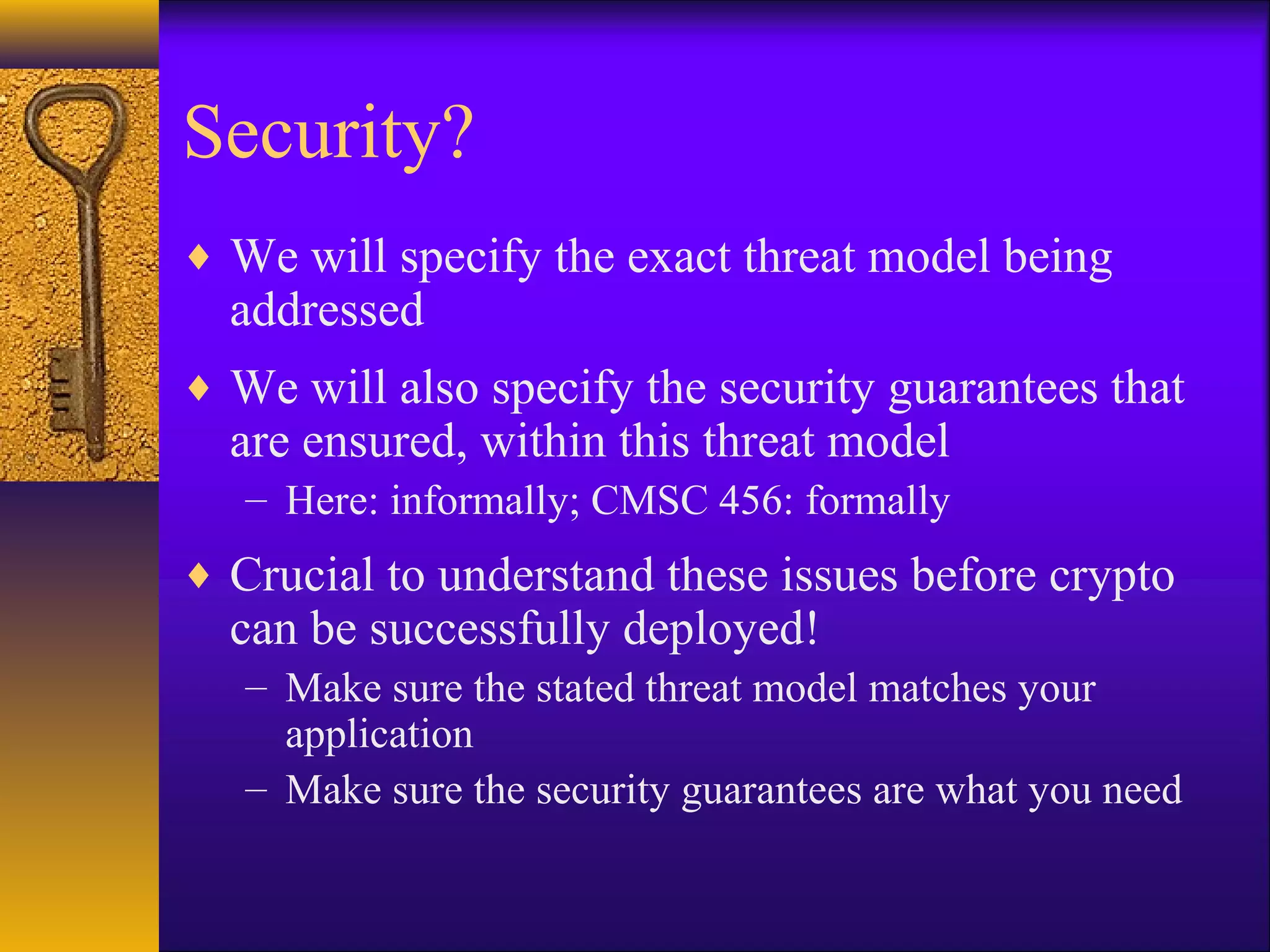

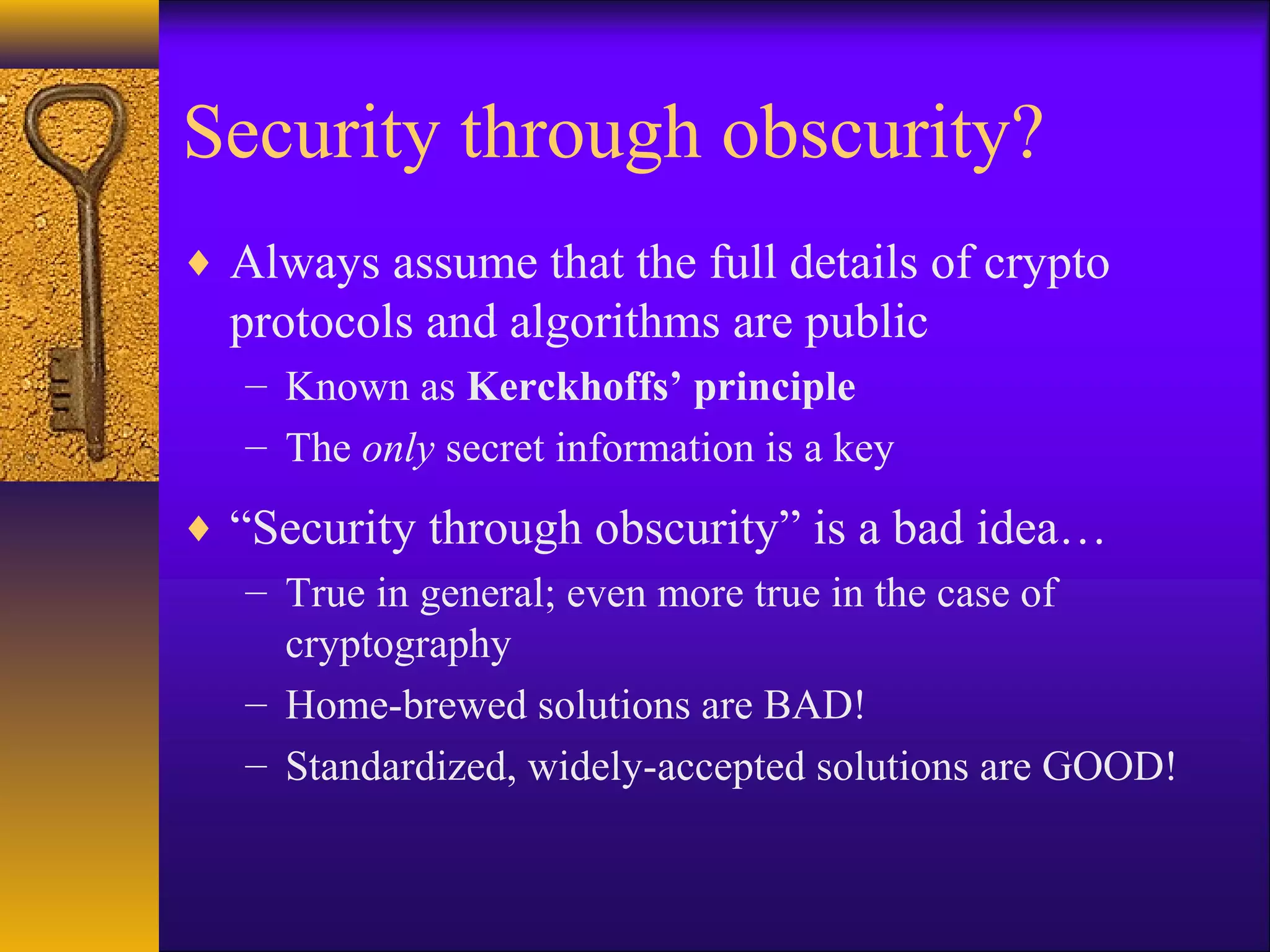

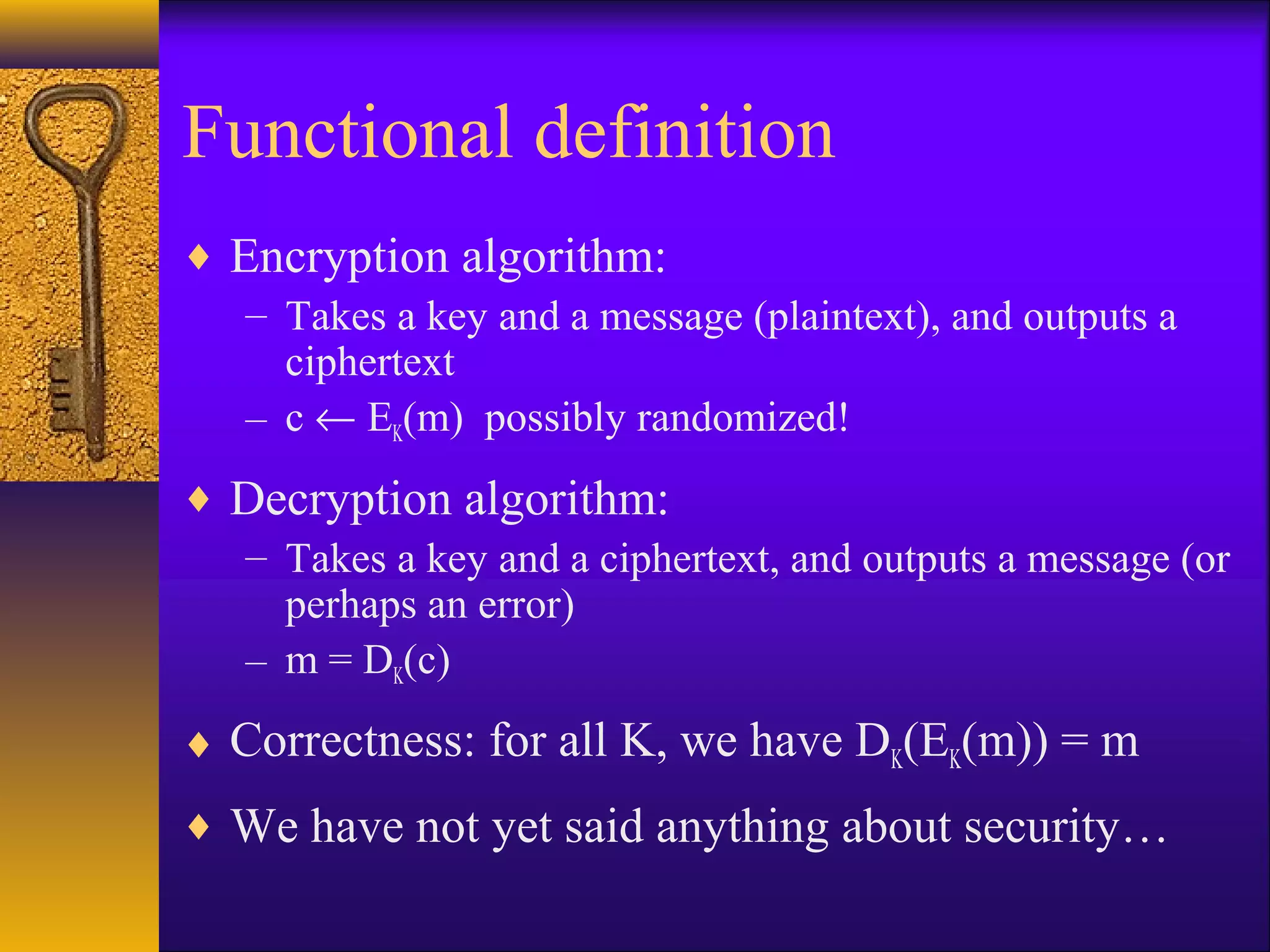

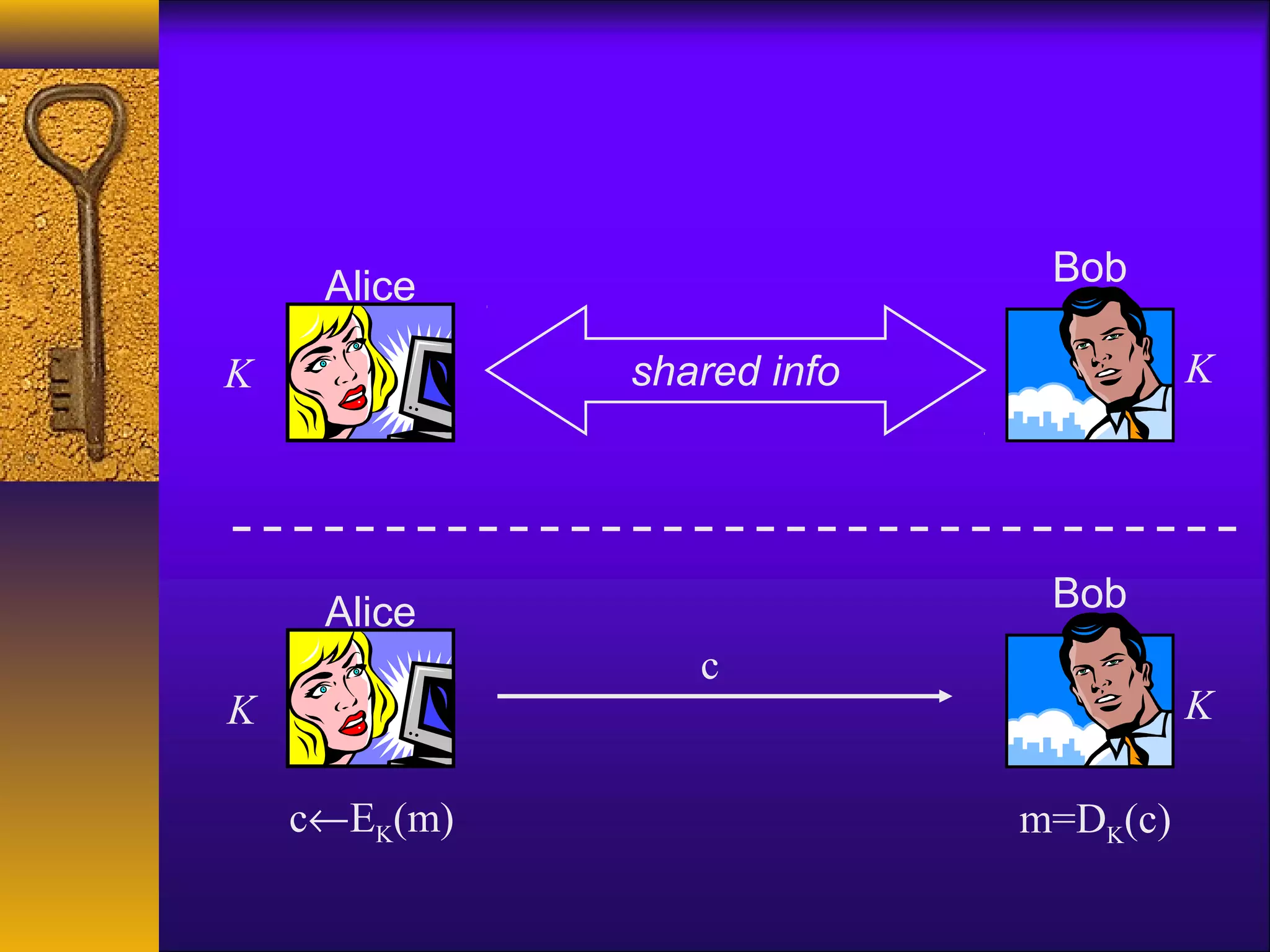

This document provides an overview of a lecture on computer and network security. It discusses an upcoming JCE tutorial and homework assignment. It also lists assigned readings and asks for comments. The rest of the document summarizes a high-level survey of cryptography, covering goals like confidentiality and integrity. It discusses private-key settings where parties share a secret key, and provides examples of simple encryption schemes like shift ciphers and their limitations. It emphasizes using standardized cryptographic algorithms.

![Defining secrecy (take 1)

♦ Even an adversary running for an unbounded

amount of time learns nothing about the message

from the ciphertext

♦ Perfect secrecy

♦ Formally, for all distributions over the message

space, all m, and all c:

Pr[M=m | C=c] = Pr[M=m]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture2-160712051129/75/Computer-and-Network-Security-29-2048.jpg)